2025年4月19日·8 分

モダンフレームワークにおける認証と認可の扱い

セッション、トークン、OAuth/OIDC、ミドルウェア、ロール、ポリシーなどを含め、モダンフレームワークが認証と認可をどのように実装するか、主要なセキュリティ上の注意点とともに解説します。

セッション、トークン、OAuth/OIDC、ミドルウェア、ロール、ポリシーなどを含め、モダンフレームワークが認証と認可をどのように実装するか、主要なセキュリティ上の注意点とともに解説します。

Authentication answers “who are you?” Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do?” Modern frameworks treat them as related but distinct concerns, and that separation is one of the main reasons security can stay consistent as an app grows.

Authentication is about proving a user (or service) is who they claim to be. Frameworks usually don’t hard-code a single method; instead, they provide extension points for common options such as password login, social login, SSO, API keys, and service credentials.

The output of authentication is an identity: a user ID, account status, and sometimes basic attributes (like whether an email is verified). Importantly, authentication should not decide whether an action is permitted—only who is making the request.

Authorization uses the established identity plus request context (route, resource owner, tenant, scopes, environment, etc.) to decide if an action is allowed. This is where roles, permissions, policies, and resource-based rules live.

Frameworks separate authorization rules from authentication so you can:

Most frameworks enforce rules through centralized points in the request lifecycle:

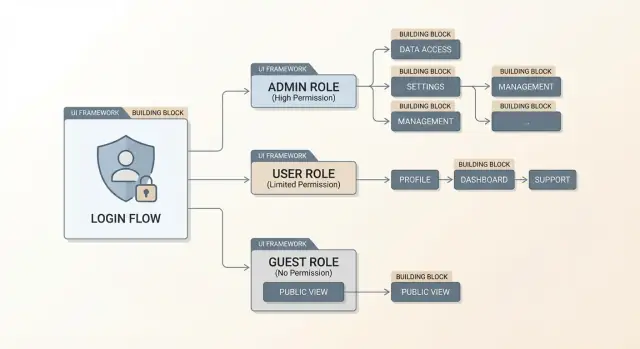

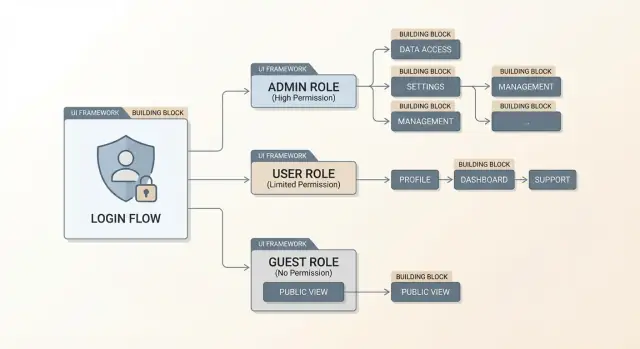

Even though names differ, the building blocks are familiar: an identity store (users and credentials), a session or token that carries identity between requests, and middleware/guards that enforce authentication and authorization consistently.

The examples in this article stay conceptual so you can map them to your framework of choice.

Before a framework can “log someone in,” it needs two things: a place to look up identity data (the identity store) and a consistent way to represent that identity in code (the user model). Many “authentication features” in modern frameworks are abstractions around these two pieces.

Frameworks usually support multiple backends, either built-in or via plugins:

The key difference is who is the source of truth. With database users, your app owns credentials and profile data. With an IdP or directory, your app often stores a “local shadow user” that links to the external identity.

Even when frameworks generate a default user model, most teams standardize a few fields:

is_verified, is_active, is_locked, deleted_at.These flags matter because authentication isn’t just “correct password?”—it’s also “is this account allowed to sign in right now?”

A practical identity store supports common lifecycle events: registration, email/phone verification, password reset, session revocation after sensitive changes, and deactivation or soft-deletion. Frameworks often provide primitives (tokens, timestamps, hooks), but you still define the rules: expiry windows, rate limits, and what happens to existing sessions when an account is disabled.

Most modern frameworks offer extension points like user providers, adapters, or repositories. These components translate “given a login identifier, fetch the user” and “given a user ID, load the current user” into your chosen store—whether that’s a SQL query, a call to an IdP, or an enterprise directory lookup.

Session-based authentication is the “classic” approach many web frameworks still default to—especially for server-rendered apps. The idea is simple: the server remembers who you are, and the browser holds a small pointer to that memory.

After a successful login, the framework creates a server-side session record (often a random session ID mapped to a user). The browser receives a cookie containing that session ID. On every request, the browser automatically sends the cookie back, and the server uses it to look up the logged-in user.

Because the cookie is only an identifier (not user data itself), sensitive information stays on the server.

Modern frameworks try to make session cookies harder to steal or misuse by setting secure defaults:

You’ll often see these configured under “session cookie settings” or “security headers.”

Frameworks usually let you choose a session store:

At a high level, the trade-off is speed vs. durability vs. operational complexity.

Logout can mean two different things:

Frameworks often implement “logout everywhere” by tracking a user “session version,” storing multiple session IDs per user, and revoking them. If you need stronger control (like immediate revocation), session-based auth is often simpler than tokens because the server can forget a session instantly.

Token-based authentication replaces server-side session lookups with a string the client presents on every request. Frameworks typically recommend tokens when your server is primarily an API (used by multiple clients), when you have mobile apps, when you’re building an SPA talking to a separate backend, or when services need to call each other without browser sessions.

A token is an access credential issued after login (or after an OAuth flow). The client sends it back on later requests so the server can authenticate the caller and then authorize the action. Most frameworks treat this as a first-class pattern: an “issue token” endpoint, authentication middleware that validates the token, and guards/policies that run after identity is established.

Opaque tokens are random strings with no meaning to the client (for example, tX9...). The server validates them by looking up a database or cache entry. This makes revocation straightforward and keeps token contents private.

JWTs (JSON Web Tokens) are structured and signed. A JWT typically contains claims such as a user identifier (sub), issuer (iss), audience (aud), issued/expiry times (iat, exp), and sometimes roles/scopes. Important: JWTs are encoded, not encrypted by default—anyone holding the token can read its claims, even if they can’t forge a new one.

Framework guidance usually converges on two safer defaults:

Authorization: Bearer <token> header for APIs. This avoids CSRF risks that come with automatically sent cookies, but it raises the bar for XSS defenses because JavaScript can typically read and attach tokens.HttpOnly, Secure, and SameSite, and when you’re prepared to handle CSRF properly (often paired with separate CSRF tokens).Access tokens are kept short-lived. To avoid forcing constant logins, many frameworks support refresh tokens: a long-lived credential used only to mint new access tokens.

A common structure is:

POST /auth/login → returns access token (and refresh token)POST /auth/refresh → rotates the refresh token and returns a new access tokenPOST /auth/logout → invalidates refresh tokens server-sideRotation (issuing a new refresh token every time) limits damage if a refresh token is stolen, and many frameworks provide hooks to store token identifiers, detect reuse, and revoke sessions quickly.

OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect (OIDC) are often mentioned together, but frameworks treat them differently because they solve different problems.

Use OAuth 2.0 when you need delegated access: your app gets permission to call an API on a user’s behalf (for example, read a calendar or post to a repo) without handling the user’s password.

Use OpenID Connect when you need login/identity: your app wants to know who the user is and receive an ID token with identity claims. In practice, “Login with X” is usually OIDC on top of OAuth 2.0.

Most modern frameworks and their auth libraries focus on two flows:

Framework integrations typically provide a callback route and helper middleware, but you still need to configure the essentials correctly:

Frameworks usually normalize provider data into a local user model. The key design decision is what actually drives authorization:

A common pattern is: map stable identifiers (like sub) to a local user, then translate provider roles/groups/claims into local roles or policies your app controls.

Passwords are still the default sign-in method in many apps, so frameworks tend to ship with safer storage patterns and common guardrails. The core rule is unchanged: you should never store a password (or a simple hash of it) in your database.

Modern frameworks and their auth libraries usually default to purpose-built password hashers like bcrypt, Argon2, or scrypt. These algorithms are intentionally slow and include salting, which helps prevent precomputed table attacks and makes large-scale cracking expensive.

A plain cryptographic hash (like SHA-256) is unsafe for passwords because it’s designed to be fast. If a database leaks, fast hashes let attackers guess billions of passwords quickly. Password hashers add work factors (cost parameters) so you can tune security as hardware improves.

Frameworks typically provide hooks (or middleware/plugins) to enforce sensible rules without hard-coding them into every endpoint:

Most ecosystems support adding MFA as a second step after password verification:

Password reset is a common attack path, so frameworks usually encourage patterns like:

A good rule: make recovery easy for legitimate users, but costly for attackers to automate.

Most modern frameworks treat security as part of the request pipeline: a series of steps that run before (and sometimes after) your controller/handler. The names vary—middleware, filters, guards, interceptors—but the idea is consistent: each step can read the request, add context, or stop processing.

A typical flow looks like this:

/account/settings).Frameworks encourage you to keep security checks outside business logic, so controllers stay focused on “what to do” rather than “who can do it.”

Authentication is the step where the framework establishes user context from cookies, session IDs, API keys, or bearer tokens. If successful, it creates a request-scoped identity—often exposed as a user, principal, or context.auth object.

This attachment is crucial because later steps (and your app code) shouldn’t re-parse headers or re-validate tokens. They should read the already-populated user object, which typically includes:

Authorization is commonly implemented as:

That second type explains why authorization hooks often sit close to controllers and services: they may need route params or database-loaded objects to decide correctly.

Frameworks distinguish two common failure modes:

Well-designed systems avoid leaking details in 403 responses; they deny access without explaining which rule failed.

Authorization answers a narrower question than login: “Is this signed-in user allowed to do this specific thing right now?” Modern frameworks usually support several models, and many teams combine them.

RBAC assigns users one or more roles (e.g., admin, support, member) and gates features based on those roles.

It’s easy to reason about and quick to implement, especially when frameworks offer helpers like requireRole('admin'). Role hierarchies (“admin implies manager implies member”) can reduce duplication, but they can also hide privilege: a small change to a parent role may silently grant access across the app.

RBAC works best for broad, stable distinctions.

Permission-based authorization checks an action against a resource, often expressed as:

read, create, update, delete, inviteinvoice, project, user, sometimes with an ID or ownershipThis model is more precise than RBAC. For example, “can update projects” is different from “can update only projects they own,” which requires checking both permissions and data conditions.

Frameworks often implement this via a central “can?” function (or service) called from controllers, resolvers, workers, or templates.

Policies package authorization logic into reusable evaluators: “A user may delete a comment if they authored it or are a moderator.” Policies can accept context (user, resource, request), making them ideal for:

When frameworks integrate policies into routing and middleware, you can enforce rules consistently across endpoints.

Annotations (e.g., @RequireRole('admin')) keep intent close to the handler, but can become fragmented when rules get complex.

Code-based checks (explicit calls to an authorizer) are more verbose, but typically easier to test and refactor. A common compromise is annotations for coarse gates and policies for the detailed logic.

Modern frameworks don’t just help you log users in—they also ship with defenses for the most common “web glue” attacks that happen around authentication.

If your app uses session cookies, the browser automatically attaches them to requests—sometimes even when the request is triggered from another site. Framework CSRF protection typically adds a per-session (or per-request) CSRF token that must be sent alongside state-changing requests.

Common patterns:

Pair CSRF tokens with SameSite cookies (often Lax by default) to reduce risk, and ensure your session cookie is HttpOnly and Secure where appropriate.

CORS is not an auth mechanism; it’s a browser permission system. Frameworks usually provide middleware/config to allow trusted origins to call your API.

Misconfigurations to avoid:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * together with Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true (browsers will reject it, and it signals confusion).Origin header without a strict allowlist.Authorization) or methods, causing clients to “work in curl but fail in the browser.”Most frameworks can set safe defaults or make it easy to add headers such as:

X-Frame-Options or Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors to prevent clickjacking.Content-Security-Policy (broader script/resource controls).Referrer-Policy and X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff for safer browser behavior.Validation ensures data is well-formed; authorization ensures the user is allowed to act. A valid request can still be forbidden—frameworks work best when you apply both: validate inputs early, then enforce permissions on the specific resource being accessed.

The “right” auth pattern depends heavily on where your code runs and how requests reach your backend. Frameworks may support multiple options, but the defaults that feel natural in one app type can be awkward (or risky) in another.

SSR frameworks usually pair best with cookie-based sessions. The browser automatically sends the cookie, the server looks up the session, and pages can render with user context without extra client code.

A practical rule: keep session cookies HttpOnly, Secure, and with a sensible SameSite setting, and rely on server-side authorization checks for every request that renders private data.

SPAs often call APIs from JavaScript, which makes token choices more visible. Many teams prefer an OAuth/OIDC flow that yields short-lived access tokens.

Avoid storing long-lived tokens in localStorage when you can; it increases the blast radius of XSS. A common alternative is a backend-for-frontend (BFF) pattern: the SPA talks to your own server with a session cookie, and the server exchanges/holds tokens for upstream APIs.

Mobile apps can’t rely on browser cookie rules in the same way. They typically use OAuth/OIDC with PKCE, and store refresh tokens in the platform’s secure storage (Keychain/Keystore).

Plan for “lost device” recovery: revoke refresh tokens, rotate credentials, and make re-authentication smooth—especially when MFA is enabled.

With many services, you’ll choose between centralized identity and service-level enforcement:

For service-to-service authentication, frameworks commonly integrate with either mTLS (strong channel identity) or OAuth client credentials (service accounts). The key is to authenticate the caller and authorize what it may do.

Admin “impersonate user” features are powerful and dangerous. Prefer explicit impersonation sessions, require re-authentication/MFA for admins, and always write audit logs (who impersonated whom, when, and what actions were taken).

Security features only help if they keep working when the code changes. Modern frameworks make it easier to test authentication and authorization, but you still need tests that reflect real user behavior—and real attacker behavior.

Start by separating what you test:

Most frameworks ship with test helpers so you don’t have to hand-roll sessions or tokens every time. Common patterns include:

A practical rule: for every “happy path” test, add one “should be denied” test that proves the authorization check actually runs.

If you’re iterating quickly on these flows, tools that support rapid prototyping plus safe rollback can help. For example, Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform) can generate a React front end and a Go + PostgreSQL backend from a chat-based spec, then let you use snapshots and rollback while you refine middleware/guards and policy checks—useful when you’re experimenting with session vs token approaches and want to keep changes auditable.

When something goes wrong, you want answers quickly and confidently.

Log and/or audit key events:

Add lightweight metrics too: rate of 401/403 responses, spikes in failed logins, and unusual token refresh patterns.

Treat auth bugs as testable behavior: if it can regress, it deserves a test.

認証は身元の検証(リクエストを行っているのは誰か)を行います。認可はアクセスの判断(その身元が何をできるか)を、ルート、リソース所有者、テナント、スコープなどのコンテキストを使って行います。

フレームワークは両者を分離することで、サインイン方法を変えても権限ロジックを書き直す必要がなくなります。

多くのフレームワークはリクエストパイプライン内で認証・認可を実施します。典型的には:

user/principal をアタッチアイデンティティストアはユーザーや資格情報の真実のソース(あるいは外部IDへのリンク)です。ユーザーモデルはコード内でその身元を表す方法です。

実務では、フレームワークは両方を必要とします:"この識別子/トークンが与えられたとき、現在のユーザーは誰か?" に答えるためです。

一般的な統合先は次のとおりです:

IdPやディレクトリを使う場合、多くは外部の安定した識別子(OIDCの sub など)をローカルの“シャドウユーザー”に紐づけます。

セッションはサーバー側に識別を保持し、ブラウザ側はそのポインタ(クッキー)を持ちます。SSRに向いており、無効化が容易です。

トークン(JWT/opaque)は各リクエストで送られる資格情報で、API、SPA、モバイル、サービス間の認証に適しています。

フレームワークはセッション用クッキーを次のように強化することが多いです:

HttpOnly(XSSによるクッキー取得を抑制)Secure(HTTPSのみ送信)SameSite(クロスサイト送信の制御;CSRFや外部認証フローに影響)アプリの要求に応じて Lax と None などを適切に選んでください。

不透明トークン(opaque)はランダム文字列で、サーバーがデータベースやキャッシュで照合して検証します(失効が容易)。

JWTは署名された自己完結型トークンで、sub や exp、ロールやスコープなどのクレームを含みます。読み取りは可能ですが(署名で改竄は防ぐ)、失効を扱うのはやや難しいため、短命化やサーバー側制御が必要です。

アクセストークンは短命に保ち、長寿命のリフレッシュトークンで新しいアクセストークンを発行します。

一般的なエンドポイント例:

POST /auth/login → access + refreshPOST /auth/refresh → refreshをローテーションして新しいaccessを返すPOST /auth/logout → リフレッシュトークンを無効化ローテーションと再利用検出により、リフレッシュトークン漏洩の被害を限定できます。

OAuth 2.0 は委任アクセス(アプリがユーザーの代わりにAPIを呼ぶ許可)向けです。

OpenID Connect(OIDC)はログイン/アイデンティティ向けで、IDトークンや標準化されたクレームを追加します。

「◯◯でログイン」は多くの場合、OAuth 2.0 上の OIDC です。

RBAC(ロール)は広い範囲の権限付与に簡便です。権限(permission)やポリシーはリソースや行動に対する細かなルールを表現します。

一般的な組み合わせ: