30 ਅਗ 2025·8 ਮਿੰਟ

Nginx vs HAProxy: Choosing the Right Reverse Proxy

Nginx ਅਤੇ HAProxy ਦੀ ਤੁਲਨਾ ਕਰੋ: ਪ੍ਰਦਰਸ਼ਨ, ਲੋਡ ਬੈਲਾਂਸਿੰਗ, TLS, ਦ੍ਰਸ਼ਯਤਾ, ਸੁਰੱਖਿਆ ਅਤੇ ਆਮ ਸੈਟਅਪ — ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵਧੀਆ ਕਿਹੜਾ ਢੂੰਢਣਾ ਹੈ।

Nginx ਅਤੇ HAProxy ਦੀ ਤੁਲਨਾ ਕਰੋ: ਪ੍ਰਦਰਸ਼ਨ, ਲੋਡ ਬੈਲਾਂਸਿੰਗ, TLS, ਦ੍ਰਸ਼ਯਤਾ, ਸੁਰੱਖਿਆ ਅਤੇ ਆਮ ਸੈਟਅਪ — ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵਧੀਆ ਕਿਹੜਾ ਢੂੰਢਣਾ ਹੈ।

A reverse proxy is a server that sits in front of your applications and receives client requests first. It forwards each request to the right backend service (your app servers) and returns the response to the client. Users talk to the proxy; the proxy talks to your apps.

A forward proxy works the other way around: it sits in front of clients (for example, inside a company network) and forwards their outbound requests to the internet. It’s mainly about controlling, filtering, or hiding client traffic.

A load balancer is often implemented as a reverse proxy, but with a specific focus: distributing traffic across multiple backend instances. Many products (including Nginx and HAProxy) do both reverse proxying and load balancing, so the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Most deployments start for one or more of these reasons:

/api to an API service, / to a web app).Reverse proxies commonly front websites, APIs, and microservices—either at the edge (public internet) or internally between services. In modern stacks, they’re also used as building blocks for ingress gateways, blue/green deployments, and high-availability setups.

Nginx and HAProxy overlap, but they differ in emphasis. In the sections ahead, we’ll compare decision factors like performance under many connections, load balancing and health checks, protocol support (HTTP/2, TCP), TLS features, observability, and day-to-day configuration and operations.

Nginx is widely used as both a web server and a reverse proxy. Many teams start with it to serve a public website and later expand its role to sit in front of application servers—handling TLS, routing traffic, and smoothing over spikes.

Nginx shines when your traffic is primarily HTTP(S) and you want a single “front door” that can do a bit of everything. It’s especially strong at:

X-Forwarded-For, security headers)Because it can both serve content and proxy to apps, Nginx is a common choice for small-to-medium setups where you want fewer moving parts.

Popular capabilities include:

Nginx is often chosen when you need one entry point for:

If your priority is rich HTTP handling and you like the idea of combining web serving and reverse proxying, Nginx is frequently the default starting point.

HAProxy (High Availability Proxy) is most commonly used as a reverse proxy and load balancer that sits in front of one or more application servers. It accepts incoming traffic, applies routing and traffic rules, and forwards requests to healthy backends—often while keeping response times stable under heavy concurrency.

Teams typically deploy HAProxy for traffic management: spreading requests across multiple servers, keeping services available during failures, and smoothing out traffic spikes. It’s a frequent choice at the “edge” of a service (north–south traffic) and also between internal services (east–west), especially when you need predictable behavior and strong control over connection handling.

HAProxy is known for efficient handling of large numbers of concurrent connections. That matters when you have many clients connected at once (busy APIs, long-lived connections, chatty microservices) and want the proxy to stay responsive.

Its load balancing capabilities are a major reason people pick it. Beyond simple round-robin, it supports multiple algorithms and routing strategies that help you:

Health checks are another strong point. HAProxy can actively verify backend health and automatically remove unhealthy instances from rotation, then re-add them once they recover. In practice, this reduces downtime and prevents “half-broken” deployments from affecting all users.

HAProxy can operate at Layer 4 (TCP) and Layer 7 (HTTP).

The practical difference: L4 is generally simpler and very fast for TCP forwarding, while L7 gives you richer routing and request logic when you need it.

HAProxy is often the pick when the primary goal is reliable, high-performance load balancing with strong health checking—for example, distributing API traffic across multiple app servers, managing failover between availability zones, or fronting services where connection volume and predictable traffic behavior matter more than advanced web server features.

Performance comparisons often go wrong because people look at a single number (like “max RPS”) and ignore what users feel.

A proxy can increase throughput while still making tail latency worse if it queues too much work under load.

Think about your application’s “shape":

If you benchmark with one pattern but deploy another, results won’t transfer.

Buffering can help when clients are slow or bursty, because the proxy can read the full request (or response) and feed your app at a steadier pace.

Buffering can hurt when your app benefits from streaming (server-sent events, large downloads, real-time APIs). Extra buffering adds memory pressure and can increase tail latency.

Measure more than “max RPS":

If p95 climbs sharply before errors appear, you’re seeing early warning signs of saturation—not “free headroom.”

Both Nginx and HAProxy can sit in front of multiple application instances and spread traffic across them, but they differ in how deep their load-balancing feature set goes out of the box.

Round-robin is the default “good enough” choice when your backends are similar (same CPU/memory, same request cost). It’s simple, predictable, and works well for stateless apps.

Least connections is useful when requests vary in duration (file downloads, long API calls, chat/websocket-ish workloads). It tends to keep slower servers from getting overwhelmed, because it favors the backend currently handling fewer active requests.

Weighted balancing (round-robin with weights, or weighted least connections) is the practical option when servers aren’t identical—mixing old and new nodes, different instance sizes, or gradually shifting traffic during a migration.

In general, HAProxy offers more algorithm choices and fine-grained control at Layer 4/7, while Nginx covers the common cases cleanly (and can be extended depending on edition/modules).

Stickiness keeps a user routed to the same backend across requests.

Use persistence only when you must (legacy server-side sessions). Stateless apps usually scale and recover better without it.

Active health checks periodically probe backends (HTTP endpoint, TCP connect, expected status). They catch failures even when traffic is low.

Passive health checks react to real traffic: timeouts, connection errors, or bad responses mark a server as unhealthy. They’re lightweight but may take longer to detect problems.

HAProxy is widely known for rich health-check and failure-handling controls (thresholds, rise/fall counts, detailed checks). Nginx supports solid checks as well, with capabilities depending on build and edition.

For rolling deploys, look for:

Whichever you choose, pair draining with short, well-defined timeouts and a clear “ready/unready” health endpoint so traffic shifts smoothly during deploys.

Reverse proxies sit on the edge of your system, so protocol and TLS choices affect everything from browser performance to how safely services talk to each other.

Both Nginx and HAProxy can “terminate” TLS: they accept encrypted connections from clients, decrypt traffic, then forward requests to your apps over HTTP or re-encrypted TLS.

The operational reality is certificate management. You’ll need a plan for:

Nginx is frequently chosen when TLS termination is paired with web-server features (static files, redirects). HAProxy is often chosen when TLS is primarily part of a traffic-management layer (load balancing, connection handling).

HTTP/2 can reduce page load times for browsers by multiplexing multiple requests over one connection. Both tools support HTTP/2 on the client-facing side.

Key considerations:

If you need to route non-HTTP traffic (databases, SMTP, Redis, custom protocols), you need TCP proxying rather than HTTP routing. HAProxy is widely used for high-performance TCP load balancing with fine-grained connection controls. Nginx can proxy TCP as well (via its stream capabilities), which can be sufficient for straightforward pass-through setups.

mTLS verifies both sides: clients present certificates, not just servers. It fits well for service-to-service communication, partner integrations, or zero-trust designs. Either proxy can enforce client cert validation at the edge, and many teams also use mTLS internally between the proxy and upstream services to reduce “trusted network” assumptions.

Reverse proxies sit in the middle of every request, so they’re often the best place to answer “what happened?” Good observability means consistent logs, a small set of high-signal metrics, and a repeatable way to debug timeouts and gateway errors.

At minimum, keep access logs and error logs enabled in production. For access logs, include upstream timing so you can tell whether slowness came from the proxy or the application.

In Nginx, common fields are request time and upstream timing (e.g., $request_time, $upstream_response_time, $upstream_status). In HAProxy, enable HTTP log mode and capture timing fields (queue/connect/response times) so you can separate “waiting for a backend slot” from “backend was slow.”

Keep logs structured (JSON if possible) and add a request ID (from an incoming header or generated) to correlate proxy logs with app logs.

Whether you scrape Prometheus or ship metrics elsewhere, export a consistent set:

Nginx often uses the stub status endpoint or a Prometheus exporter; HAProxy has a built-in stats endpoint that many exporters read.

Expose a lightweight /health (process is up) and /ready (can reach dependencies) endpoint. Use them both in automation: load balancer health checks, deployments, and auto-scaling decisions.

When troubleshooting, compare proxy timing (connect/queue) to upstream response time. If connect/queue is high, add capacity or adjust load balancing; if upstream time is high, focus on the application and database.

Running a reverse proxy isn’t just about peak throughput—it’s also about how quickly your team can make safe changes at 2pm (or 2am).

Nginx configuration is directive-based and hierarchical. It reads like “blocks inside blocks” (http → server → location), which many people find approachable when they think in terms of sites and routes.

HAProxy configuration is more “pipeline-like": you define frontends (what you accept), backends (where you send traffic), and then attach rules (ACLs) to connect the two. It can feel more explicit and predictable once you internalize the model, especially for traffic routing logic.

Nginx typically reloads config by starting new workers and gracefully draining old ones. This is friendly to frequent route updates and certificate renewals.

HAProxy can also do seamless reloads, but teams often treat it more like an “appliance”: tighter change control, clear versioned config, and careful coordination around reload commands.

Both support config testing before reload (a must for CI/CD). In practice, you’ll likely keep configs DRY by generating them:

The key operational habit: treat the proxy config as code—reviewed, tested, and deployed like application changes.

As the number of services grows, certificate and routing sprawl becomes the real pain point. Plan for:

If you expect hundreds of hosts, consider centralizing patterns and generating configs from service metadata rather than hand-editing files.

If you’re building and iterating on multiple services, a reverse proxy is only one part of the delivery pipeline—you still need repeatable app scaffolding, environment parity, and safe rollouts.

Koder.ai can help teams move faster from “idea” to running services by generating React web apps, Go + PostgreSQL backends, and Flutter mobile apps through a chat-based workflow, then supporting source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, and snapshots with rollback. In practice, that means you can prototype an API + web frontend, deploy it, and then decide whether Nginx or HAProxy is the better front door based on real traffic patterns rather than guesswork.

Security is rarely about one “magic” feature—it's about reducing the blast radius and tightening defaults around traffic you don’t fully control.

Run the proxy with the least privilege possible: bind to privileged ports via capabilities (Linux) or a fronting service, and keep worker processes unprivileged. Lock down config and key material (TLS private keys, DH params) to read-only by the service account.

At the network layer, allow inbound only from expected sources (internet → proxy; proxy → backends). Deny direct access to backends whenever feasible, so the proxy is the single choke point for authentication, rate limits, and logging.

Nginx has first-class primitives like request rate limiting and connection limiting (often via limit_req / limit_conn). HAProxy typically uses stick tables to track request rates, concurrent connections, or error patterns and then deny, tarp it, or slow down abusive clients.

Pick an approach that matches your threat model:

Be explicit about which headers you trust. Only accept X-Forwarded-For (and friends) from known upstreams; otherwise attackers can spoof client IPs and bypass IP-based controls. Similarly, validate or set Host to prevent host-header attacks and cache poisoning.

A simple rule of thumb: the proxy should set forwarding headers, not blindly pass them through.

Request smuggling often exploits ambiguous parsing (conflicting Content-Length / Transfer-Encoding, odd whitespace, or invalid header formatting). Prefer strict HTTP parsing modes, reject malformed headers, and set conservative limits:

Connection, Upgrade, and hop-by-hop headersThese controls differ in syntax between Nginx and HAProxy, but the outcome should be the same: fail closed on ambiguity and keep limits explicit.

Reverse proxies tend to get introduced in one of two ways: as a dedicated front door for a single application, or as a shared gateway that sits in front of many services. Both Nginx and HAProxy can do either—what matters is how much routing logic you need at the edge and how you want to operate it day to day.

This pattern puts a reverse proxy directly in front of a single web app (or a small set of tightly related services). It’s a great fit when you mainly need TLS termination, HTTP/2, compression, caching (if using Nginx), or clean separation between “public internet” and “private app.”

Use it when:

Here, one (or a small cluster) of proxies routes traffic to multiple applications based on hostname, path, headers, or other request properties. This reduces the number of public entry points but increases the importance of clean configuration management and change control.

Use it when:

app1.example.com, app2.example.com) and want a single ingress layer.Proxies can split traffic between “old” and “new” versions without changing DNS or the application code. A common approach is to define two upstream pools (blue and green) or two backends (v1 and v2) and shift traffic gradually.

Typical uses:

This is especially handy when your deployment tooling can’t do weighted rollouts itself, or when you want a consistent rollout mechanism across teams.

A single proxy is a single point of failure. Common HA patterns include:

Pick based on your environment: VRRP is popular on traditional VMs/bare metal; managed load balancers are often simplest in cloud.

A typical “front-to-back” chain is: CDN (optional) → WAF (optional) → reverse proxy → application.

If you already use a CDN/WAF, keep the proxy focused on application delivery and routing rather than trying to make it your only security layer.

Kubernetes changes how you “front” applications: services are ephemeral, IPs change, and routing decisions often happen at the edge of the cluster through an Ingress controller. Both Nginx and HAProxy can fit well here, but they tend to shine in slightly different roles.

In practice, the decision is rarely “which is better,” and more “which matches your traffic patterns and how much HTTP manipulation you need at the edge.”

If you run a service mesh (e.g., mTLS and traffic policies between services), you can still keep Nginx/HAProxy at the perimeter for north–south traffic (internet to cluster). The mesh handles east–west traffic (service to service). This division keeps edge concerns—TLS termination, WAF/rate limiting, basic routing—separate from internal reliability features like retries and circuit breaking.

gRPC and long-lived connections stress proxies differently than short HTTP requests. Watch for:

Whichever you choose, test with realistic durations (minutes/hours), not just quick smoke tests.

Treat proxy config as code: keep it in Git, validate changes in CI (linting, config test), and roll out via CD using controlled deployments (canary or blue/green). This makes upgrades safer and gives you a clear audit trail when a routing or TLS change affects production.

The fastest way to decide is to start from what you expect the proxy to do day to day: serve content, shape HTTP traffic, or strictly manage connections and balancing logic.

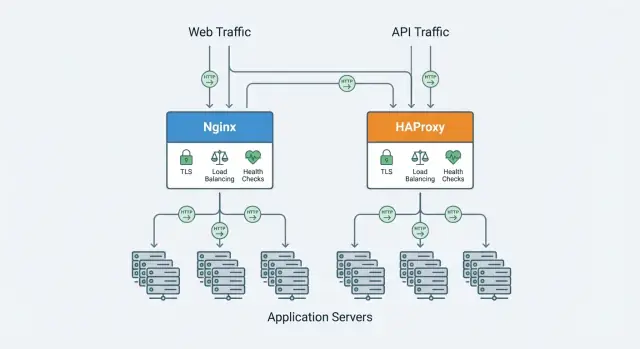

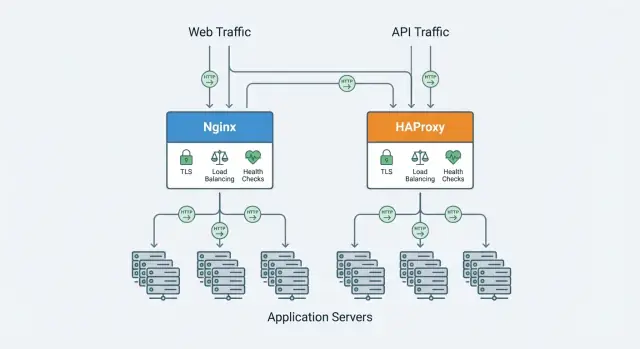

If your reverse proxy is also a “front door” for web traffic, Nginx is often the more convenient default.

If your priority is precise traffic distribution and strict control under load, HAProxy tends to shine.

Using both is common when you want web-server conveniences and specialized balancing:

This split can also help teams separate responsibilities: web concerns vs. traffic engineering.

Ask yourself:

A reverse proxy sits in front of your applications: clients connect to the proxy, and the proxy forwards requests to the correct backend service and returns the response.

A forward proxy sits in front of clients and controls outbound internet access (common in corporate networks).

A load balancer focuses on distributing traffic across multiple backend instances. Many load balancers are implemented as reverse proxies, which is why the terms overlap.

In practice, you’ll often use one tool (like Nginx or HAProxy) to do both: reverse proxying + load balancing.

Put it at the boundary where you want a single control point:

The key is to avoid letting clients hit backends directly so the proxy remains the choke point for policy and visibility.

TLS termination means the proxy handles HTTPS: it accepts encrypted client connections, decrypts them, and forwards traffic to your upstreams over HTTP or re-encrypted TLS.

Operationally, you must plan for:

Pick Nginx when your proxy is also a web “front door”:

Pick HAProxy when traffic management and predictability under load are the priority:

Use round-robin for similar backends and mostly uniform request cost.

Use least connections when request duration varies (downloads, long API calls, long-lived connections) to avoid overloading slower instances.

Use weighted variants when backends differ (instance sizes, mixed hardware, gradual migrations) so you can shift traffic intentionally.

Stickiness keeps a user routed to the same backend across requests.

Avoid stickiness if you can: stateless services scale, fail over, and roll out more cleanly without it.

Buffering can help by smoothing slow or bursty clients so your app sees steadier traffic.

It can hurt when you need streaming behavior (SSE, WebSockets, large downloads), because extra buffering increases memory pressure and can worsen tail latency.

If your app is stream-oriented, test and tune buffering explicitly rather than relying on defaults.

Start by separating proxy delay from backend delay using logs/metrics.

Common meanings:

Useful signals to compare:

Fixes usually involve adjusting timeouts, increasing backend capacity, or improving health checks/readiness endpoints.