13 dec 2025·8 min

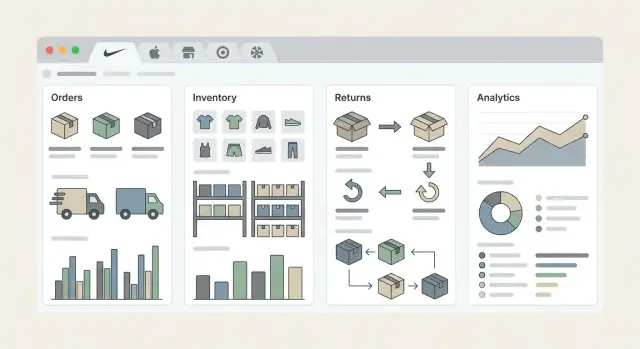

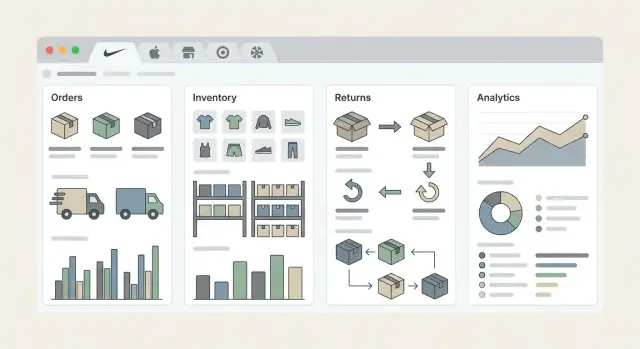

Hoe je een webapp bouwt voor een multi‑brand e‑commerce backoffice

Leer hoe je een webapp ontwerpt, bouwt en lanceert die bestellingen, voorraad, retouren en rapportage over meerdere e‑commerce merken verenigt.

Leer hoe je een webapp ontwerpt, bouwt en lanceert die bestellingen, voorraad, retouren en rapportage over meerdere e‑commerce merken verenigt.

Before you talk frameworks, databases, or integrations, define what “multi‑brand” actually means inside your business. Two companies can both sell “multiple brands” and still need completely different backoffice tools.

Start by writing down your operating model. Common patterns include:

These choices drive everything: your data model, permission boundaries, workflows, and even how you measure performance.

A multi‑brand backoffice is less about “features” and more about the daily jobs teams must complete without juggling spreadsheets. Outline the minimum set of workflows you need on day one:

If you’re unsure where to start, walk through a normal day with each team and capture where work currently “falls out” into manual exports.

Multi‑brand operations usually involve the same few roles, but with different access needs:

Document which roles need cross-brand access and which should be restricted to a single brand.

Pick measurable outcomes so you can say “this is working” after launch:

Finally, capture constraints upfront: budget, timeline, existing tools you must keep, compliance needs (tax, audit logs, data retention), and any “no‑go” rules (e.g., finance data must stay in a specific system). This becomes your decision filter for every technical choice later.

Before you design screens or pick tools, get a clear picture of how work actually moves today. Multi‑brand backoffice projects usually fail when they assume “orders are just orders” and ignore channel differences, hidden spreadsheets, and brand‑specific exceptions.

Start by listing each brand and every sales channel it uses—Shopify stores, marketplaces, a DTC site, wholesale portals—and document how orders arrive (API import, CSV upload, email, manual entry). Capture what metadata you get (tax, shipping method, line‑item options) and what’s missing.

This is also where you spot practical issues like:

Don’t keep this abstract. Collect 10–20 recent “messy” cases and write down the steps staff took to resolve them:

Quantify the cost where possible: minutes per order, number of refunds per week, or how often support needs to intervene.

For each data type, decide what system is authoritative:

List gaps clearly (e.g., “return reasons only tracked in Zendesk” or “carrier tracking stored only in ShipStation”). These gaps will shape what your web app must store vs. fetch.

Multi‑brand operations differ on the details. Record rules like packaging slip formats, return windows, preferred carriers, tax settings, and any approval steps for high‑value refunds.

Finally, prioritize workflows by frequency and business impact. High‑volume order ingestion and inventory sync usually beat edge‑case tooling, even if the edge cases are loud.

A multi‑brand backoffice gets messy when “brand differences” are handled ad hoc. The goal here is to define a small set of product modules, then decide what data and rules are global versus configurable per brand.

Most teams need a predictable core:

Treat these as modules with clean boundaries. If a feature doesn’t clearly belong to one module, it’s a warning sign it may be “v2.”

A practical default is shared data model, brand‑specific configuration. Common splits:

Identify where the system should make consistent decisions:

Set baseline targets for performance (page load and bulk actions), uptime expectations, audit logs (who changed what), and data retention policies.

Finally, publish a simple v1 vs. v2 list. Example: v1 supports returns + refunds; v2 adds exchanges with cross‑brand swaps and advanced credit logic. This single document prevents scope creep more than any meeting will.

Architecture isn’t a trophy decision—it’s a way to keep your backoffice shippable while brands, channels, and operational edge cases pile up. The right choice depends less on “best practice” and more on your team size, deployment maturity, and how quickly requirements change.

If you have a small‑to‑mid team, start with a modular monolith: one deployable app with clear internal boundaries (orders, catalog, inventory, returns, reporting). You get simpler debugging, fewer moving parts, and faster iteration.

Move to microservices only when you feel real pain: independent scaling needs, multiple teams blocked by each other, or long release cycles caused by shared deployments. If you do go there, split by business capability (e.g., “Orders Service”), not by technical layers.

A practical multi‑brand backoffice usually includes:

Keeping integrations behind a stable interface prevents “channel‑specific logic” from leaking into your core workflows.

Use dev → staging → production with production‑like staging data where possible. Make brand/channel behavior configurable (shipping rules, return windows, tax display, notification templates) using environment variables plus a database‑backed configuration table. Avoid hardcoding brand rules in the UI.

Pick boring, well‑supported tools your team can hire for and maintain: a mainstream web framework, a relational database (often PostgreSQL), a queue system for jobs, and an error/logging stack. Favor typed APIs and automated migrations.

If your main risk is speed-to-first-shippable rather than raw engineering complexity, it can also be worth prototyping the admin UI and workflows in a faster build loop before committing to months of custom work. For example, teams sometimes use Koder.ai (a vibe‑coding platform) to generate a working React + Go + PostgreSQL foundation from a planning conversation, then iterate on queues, role-based access, and integrations while keeping the option to export source code, deploy, and roll back via snapshots.

Treat files as first‑class operational artifacts. Store them in object storage (e.g., S3‑compatible), keep only metadata in your DB (brand, order, type, checksum), and generate time‑limited access URLs. Add retention rules and permissions so brand teams only see their own documents.

A multi‑brand backoffice succeeds or fails on its data model. If the “truth” about SKUs, stock, and order status is split across ad‑hoc tables, every new brand or channel will add friction.

Model the business exactly as it operates:

This separation avoids “Brand = Store” assumptions that break as soon as one brand sells on multiple channels.

Use an internal SKU as your anchor, then map it outward.

A common pattern is:

sku (internal)channel_sku (external identifier) with fields: channel_id, storefront_id, external_sku, external_product_id, status, and effective datesThis supports one internal SKU → many channel SKUs. Add first‑class support for bundles/kits via a bill‑of‑materials table (e.g., bundle SKU → component SKU + quantity). That way inventory reservation can decrement components correctly.

Inventory needs multiple “buckets” per warehouse (and sometimes per brand for ownership/accounting):

Keep calculations consistent and auditable; don’t overwrite history.

Multi‑team operations require clear answers to “what changed, when, and who did it.” Add:

created_by, updated_by, and immutable change records for critical fields (addresses, refunds, inventory adjustments)If brands sell internationally, store monetary values with currency codes, exchange rates (if needed), and tax breakdowns (tax included/excluded, VAT/GST amounts). Design this early so reporting and refunds don’t become a rewrite later.

Integrations are where multi‑brand backoffice apps either stay clean—or turn into a pile of one‑off scripts. Start by listing every system you must talk to and what “source of truth” each one owns.

At minimum, most teams integrate:

Document for each: what you pull (orders, products, inventory), what you push (fulfillment updates, cancellations, refunds), and required SLAs (minutes vs. hours).

Use webhooks for near real‑time signals (new order, fulfillment update) because they reduce delay and API calls. Add scheduled jobs as a safety net: polling for missed events, nightly reconciliation, and re‑sync after outages.

Build retries into both. A good rule: retry transient failures automatically, but route “bad data” to a human‑review queue.

Different platforms name and structure events differently. Create a normalized internal format like:

order_createdshipment_updatedrefund_issuedThis lets your UI, workflows, and reporting react to one event stream instead of dozens of vendor‑specific payloads.

Assume duplicates will happen (webhook redelivery, job reruns). Require an idempotency key per external record (e.g., channel + external_id + event_type + version), and store processed keys so you don’t double‑import or double‑trigger actions.

Treat integrations as a product feature: an ops dashboard, alerts on failure rates, an error queue with reasons, and a replay tool to reprocess events after fixes. This will save hours every week once volume grows.

A multi‑brand backoffice fails quickly if everyone can “just access everything.” Start by defining a small set of roles, then refine with permissions that match how your teams actually work.

Common baseline roles:

Avoid a single “can edit orders” switch. In multi‑brand operations, permissions often need to be scoped by:

A practical approach is role‑based access control with scopes (brand/channel/warehouse) and capabilities (view, edit, approve, export).

Decide whether users operate in:

Make the current brand context visible at all times, and when a user switches brands, reset filters and warn before cross‑brand bulk actions.

Approval flows reduce costly mistakes without slowing everyday work. Typical approvals:

Log who requested, who approved, the reason, and before/after values.

Apply least privilege, enforce session timeouts, and keep access logs for sensitive actions (refunds, exports, permission changes). These logs become essential during disputes, audits, and internal investigations.

A multi‑brand backoffice succeeds or fails on day‑to‑day usability. Your goal is a UI that helps ops teams move quickly, spot exceptions early, and take the same actions no matter where an order originated.

Start with a small set of “always‑open” screens that cover 80% of work:

Model operational reality instead of forcing teams into workarounds:

Bulk actions are where you win back hours. Make common actions safe and obvious: print labels, mark packed/shipped, assign to warehouse, add tags, export selected rows.

To keep the UI consistent across channels, normalize statuses into a small set of states (e.g., Paid / Authorized / Fulfilled / Partially Fulfilled / Refunded / Partially Refunded) and display the original channel status as a reference.

Add order and return notes that support @mentions, timestamps, and visibility rules (team‑only vs. brand‑only). A lightweight activity feed prevents repeated work and makes handoffs cleaner—especially when multiple brands share a single ops team.

If you need a single entry point for teams, link the inbox as the default route (e.g., /orders) and treat everything else as drill‑down.

Returns are where multi‑brand operations get messy fast: each brand has its own promises, packaging rules, and finance expectations. The key is to model returns as a consistent lifecycle, while letting policies vary by brand through configuration—not custom code.

Define a single set of states and required data at each step, so support, warehouse, and finance see the same truth:

Keep transitions explicit. “Received” should not imply “refunded,” and “approved” should not imply “label created.”

Use config‑driven policies per brand (and sometimes per category): return window, allowed reasons, final‑sale exclusions, who pays shipping, inspection requirements, and restocking fees. Store these rules in a versioned policy table so you can answer “what rules were active when this return was approved?”

When items come back, don’t automatically put them back into sellable stock. Classify into:

For exchanges, reserve the replacement SKU early, and release it if the return is rejected or times out.

Support partial refunds (discount allocation, shipping/tax rules), store credit (expiry, brand restrictions), and exchanges (price differences, one‑way swaps). Every action should create an immutable audit record: who approved, what changed, timestamps, original payment reference, and ledger‑friendly export fields for finance.

A multi‑brand backoffice lives or dies by whether people can answer simple questions quickly: “What’s stuck?”, “What will break today?”, and “What needs to be sent to finance?” Reports should support daily decisions first, and long‑term analysis second.

Your home screen should help operators clear work, not admire charts. Prioritize views like:

Make each number clickable into a filtered list so teams can act immediately. If you show “32 late shipments,” the next click should show those 32 orders.

Inventory reporting is most useful when it highlights risk early. Add focused views for:

These don’t need complex forecasting to be valuable—just clear thresholds, filters, and ownership.

Multi‑brand teams need apples‑to‑apples comparisons:

Standardize definitions (e.g., what counts as “shipped”) so comparisons don’t turn into debates.

CSV exports are still the bridge to accounting tools and ad‑hoc analysis. Provide ready‑made exports for payouts, refunds, taxes, and order lines—and keep field names consistent across brands and channels (e.g., order_id, channel_order_id, brand, currency, subtotal, tax, shipping, discount, refund_amount, sku, quantity). Version your export formats so changes don’t break spreadsheets.

Every dashboard should show the last sync time per channel (and per integration). If some data updates hourly and other data is real time, say so clearly—operators will trust the system more when it’s honest about freshness.

When your backoffice spans multiple brands, failures aren’t isolated—they ripple across order processing, inventory updates, and customer support. Treat reliability as a product feature, not an afterthought.

Standardize how you log API calls, background jobs, and integration events. Make logs searchable and consistent: include brand, channel, correlation ID, entity IDs (order_id, sku_id), and outcome.

Add tracing around:

This turns “inventory is wrong” from a guessing game into a timeline you can follow.

Prioritize tests around high‑impact paths:

Use a layered approach: unit tests for rules, integration tests for your DB and queue, and end‑to‑end tests for “happy path” operations. For third‑party APIs, prefer contract‑style tests with recorded fixtures so failures are predictable.

Set up CI/CD with repeatable builds, automated checks, and environment parity. Plan for:

If you need structure, document your release process alongside internal docs (e.g., /docs/releasing).

Cover the fundamentals: input validation, strict webhook signature verification, secrets management (no secrets in logs), and encryption in transit/at rest. Audit admin actions and exports, especially anything that touches PII.

Write short runbooks for: failed syncs, stuck jobs, webhook storms, carrier outages, and “partial success” scenarios. Include how to detect, how to mitigate, and how to communicate impact per brand.

A multi‑brand backoffice is only successful when it survives real operations: peak order spikes, partial shipments, missing stock, and last‑minute rule changes. Treat launch as a controlled rollout, not a “big bang.”

Start with a v1 that solves the daily pain without introducing new complexity:

If anything is shaky, prioritize accuracy over fancy automation. Ops will forgive slower workflows; they won’t forgive wrong stock or missing orders.

Pick a brand with average complexity and a single sales channel (e.g., Shopify or Amazon). Run the new backoffice in parallel with the old process for a short period so you can compare outcomes (counts, revenue, refunds, stock deltas).

Define “go/no‑go” metrics up front: mismatch rate, time‑to‑ship, support tickets, and the number of manual corrections.

For the first 2–3 weeks, collect feedback every day. Focus on workflow friction first: confusing labels, too many clicks, missing filters, and unclear exceptions. Small UI fixes often unlock more value than new features.

Once v1 is stable, schedule v2 work that reduces cost and errors:

Write down what changes when you add more brands, warehouses, channels, and order volume: onboarding checklist, data mapping rules, performance targets, and required support coverage. Keep it in a living runbook (bijv. /blog/backoffice-runbook-template).

If you’re moving fast and need a repeatable way to spin up workflows for the next brand (new roles, dashboards, and configuration screens), consider using a platform like Koder.ai to accelerate “ops tooling” builds. It’s designed to create web/server/mobile apps from a chat-driven planning flow, supports deployment and hosting with custom domains, and lets you export the source code when you’re ready to own the stack long-term.

Begin met het documenteren van je operating model:

Bepaal daarna welke data globaal moet zijn (bijv. interne SKU's) en wat per merk configureerbaar moet zijn (templates, policies, routeringsregels).

Schrijf de “dag‑één” taken op die elk team zonder spreadsheets moet kunnen doen:

Als een workflow niet frequent of hoog‑impact is, zet die dan op de v2‑lijst.

Wijs per datatypes een eigenaar aan en wees expliciet:

Maak vervolgens de gaten duidelijk (bijv. “retourredenen alleen in Zendesk”) zodat je weet wat je app moet opslaan versus ophalen.

Gebruik een interne SKU als anker en map naar kanalen:

sku (intern) stabielchannel_sku) met channel_id, storefront_id, en effective datesVermijd één enkele voorraadwaarde. Houd meerdere buckets per magazijn bij (en optioneel per eigenaar/merk):

on_handreservedavailable (afgeleid)inboundsafety_stockSla veranderingen op als events of onveranderlijke aanpassingen zodat je kunt auditen hoe een getal is veranderd.

Gebruik een hybride aanpak:

Maak elke import idempotent (sla verwerkte keys op) en stuur “slecht data” naar een review‑queue in plaats van eindeloos te retryen.

Begin met RBAC plus scopes:

Voeg goedkeuringen toe voor acties die geld of voorraad veranderen (high‑value refunds, grote/negatieve aanpassingen) en log wie aanvraagt/goedkeurt plus voor/na waarden.

Ontwerp voor snelheid en consistentie:

Normaliseer statussen (Paid/Fulfilled/Refunded, etc.) en toon de originele kanaalstatus als referentie.

Gebruik één gedeelde lifecycle met per‑merk configureerbare regels:

Zorg dat refunds/exchanges auditable zijn, inclusief gedeeltelijke refunds met belasting/discount allocatie.

Voer een gecontroleerde pilot uit:

Voor betrouwbaarheid: doorzoekbare logs met merk/kanaal/correlation IDs, retry+replay tools en backward‑compatible migraties met feature flags.

external_skuDit voorkomt de aanname “Brand = Store” die faalt zodra je kanalen toevoegt.