Aug 21, 2025·8 min

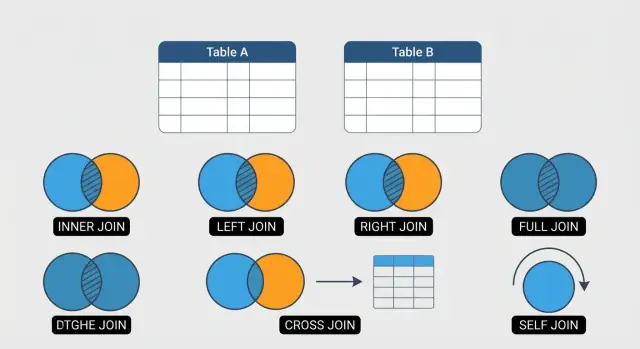

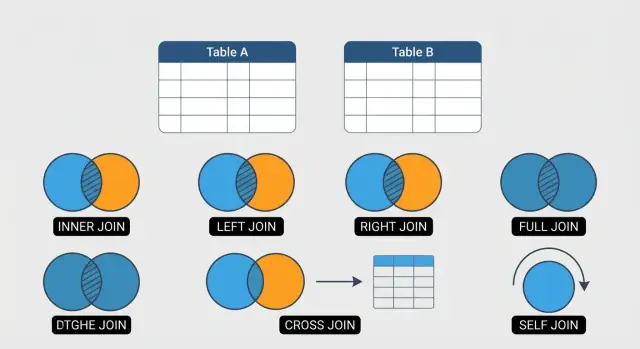

6 SQL Joins You Must Know (With Simple, Clear Examples)

Learn the 6 SQL joins every analyst should know—INNER, LEFT, RIGHT, FULL OUTER, CROSS, and SELF—with practical examples and common pitfalls.

Learn the 6 SQL joins every analyst should know—INNER, LEFT, RIGHT, FULL OUTER, CROSS, and SELF—with practical examples and common pitfalls.

A SQL JOIN lets you combine rows from two (or more) tables into one result by matching them on a related column—usually an ID.

Most real databases are intentionally split into separate tables so you don’t repeat the same information over and over. For example, a customer’s name lives in a customers table, while their purchases live in an orders table. JOINs are how you reconnect those pieces when you need answers.

That’s why JOINs show up everywhere in reporting and analysis:

Without JOINs, you’d be stuck running separate queries and manually combining results—slow, error-prone, and hard to repeat.

If you’re building products on top of a relational database (dashboards, admin panels, internal tools, customer portals), JOINs are also what turn “raw tables” into user-facing views. Platforms like Koder.ai (which generates React + Go + PostgreSQL apps from chat) still rely on solid JOIN fundamentals when you need accurate list pages, reports, and reconciliation screens—because the database logic doesn’t go away, even when development gets faster.

This guide focuses on six JOINs that cover the majority of day-to-day SQL work:

JOIN syntax is very similar across most SQL databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, SQLite). There are a few differences—especially around FULL OUTER JOIN support and some edge-case behaviors—but the concepts and core patterns transfer cleanly.

To keep the JOIN examples simple, we’ll use three small tables that mirror a common real-world setup: customers place orders, and orders may (or may not) have payments.

A small note before we start: the sample tables below show only a few columns, but some queries later reference additional fields (like order_date, created_at, status, or paid_at) to demonstrate common patterns. Treat those columns as “typical” fields you’d often have in production schemas.

Primary key: customer_id

| customer_id | name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ava |

| 2 | Ben |

| 3 | Chen |

| 4 | Dia |

Primary key: order_id

Foreign key: customer_id → customers.customer_id

| order_id | customer_id | order_total |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | 1 | 50 |

| 102 | 1 | 120 |

| 103 | 2 | 35 |

| 104 | 5 | 70 |

Notice order_id = 104 references customer_id = 5, which does not exist in customers. That “missing match” is useful for seeing how LEFT JOIN, RIGHT JOIN, and FULL OUTER JOIN behave.

Primary key: payment_id

Foreign key: order_id → orders.order_id

| payment_id | order_id | amount |

|---|---|---|

| 9001 | 101 | 50 |

| 9002 | 102 | 60 |

| 9003 | 102 | 60 |

| 9004 | 999 | 25 |

Two important “teaching” details here:

order_id = 102 has two payment rows (a split payment). When you join orders to payments, that order will show up twice—this is where duplicates often surprise people.payment_id = 9004 references order_id = 999, which doesn’t exist in orders. That creates another “unmatched” case.orders to payments will repeat order 102 because it has two related payments.An INNER JOIN returns only the rows where there’s a match in both tables. If a customer has no orders, they won’t appear in the result. If an order references a customer that doesn’t exist (bad data), that order won’t appear either.

You pick a “left” table, join a “right” table, and connect them with a condition in the ON clause.

SELECT

c.customer_id,

c.name,

o.order_id,

o.order_date

FROM customers c

INNER JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id;

The key idea is the ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id line: it tells SQL how rows relate.

If you want a list of only customers who have actually placed at least one order (and the order details), INNER JOIN is the natural choice:

SELECT

c.name,

o.order_id,

o.total_amount

FROM customers c

INNER JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id

ORDER BY o.order_id;

This is useful for things like “send an order follow-up email” or “calculate revenue per customer” (when you only care about customers with purchases).

If you write a join but forget the ON condition (or join on the wrong columns), you can accidentally create a Cartesian product (every customer combined with every order) or produce subtly wrong matches.

Bad (don’t do this):

SELECT c.name, o.order_id

FROM customers c

JOIN orders o;

Always ensure you have a clear join condition in ON (or USING in the specific cases where it applies—covered later).

A LEFT JOIN returns all rows from the left table, and adds matching data from the right table when a match exists. If there’s no match, the right-side columns show up as NULL.

Use a LEFT JOIN when you want a complete list from your primary table, plus optional related data.

Example: “Show me all customers, and include their orders if they have any.”

SELECT

c.customer_id,

c.name,

o.order_id,

o.order_date

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id

ORDER BY c.customer_id;

o.order_id (and other orders columns) will be NULL.A very common reason to use LEFT JOIN is to find items that don’t have related records.

Example: “Which customers have never placed an order?”

SELECT

c.customer_id,

c.name

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id

WHERE o.order_id IS NULL;

That WHERE ... IS NULL condition keeps only the left-table rows where the join couldn’t find a match.

LEFT JOIN can “duplicate” left-table rows when there are multiple matching rows on the right.

If one customer has 3 orders, that customer will appear 3 times—once per order. That’s expected, but it can surprise you if you’re trying to count customers.

For example, this counts orders (not customers):

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id;

If your goal is counting customers, you’d typically count the customer key instead (often with COUNT(DISTINCT c.customer_id)), depending on what you’re measuring.

A RIGHT JOIN keeps all rows from the right table, and only the matching rows from the left table. If there’s no match, the left table’s columns show up as NULL. It’s essentially a mirror image of a LEFT JOIN.

Using our example tables, imagine you want to list every payment, even if it can’t be tied back to an order (maybe the order was deleted, or the payment data is messy).

SELECT

o.order_id,

o.customer_id,

p.payment_id,

p.amount,

p.paid_at

FROM orders o

RIGHT JOIN payments p

ON o.order_id = p.order_id;

What you get:

payments is on the right).o.order_id and o.customer_id will be NULL.Most of the time, you can rewrite a RIGHT JOIN as a LEFT JOIN by swapping the table order:

SELECT

o.order_id,

o.customer_id,

p.payment_id,

p.amount,

p.paid_at

FROM payments p

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.order_id = p.order_id;

This returns the same result, but many people find it easier to read: you start with the “main” table you care about (here, payments) and then “optionally” pull in related data.

A lot of SQL style guides discourage RIGHT JOIN because it forces readers to mentally reverse the common pattern:

When optional relationships are consistently written as LEFT JOINs, queries become easier to scan.

A RIGHT JOIN can be handy when you’re editing an existing query and you realize the “must-keep” table is currently on the right. Instead of rewriting the whole query (especially a long one with several joins), switching one join to RIGHT JOIN can be a quick, low-risk change.

A FULL OUTER JOIN returns every row from both tables.

INNER JOIN).NULLs for the right table’s columns.NULLs for the left table’s columns.A classic business case is reconciling orders vs. payments:

Example:

SELECT

o.order_id,

o.customer_id,

p.payment_id,

p.amount

FROM orders o

FULL OUTER JOIN payments p

ON p.order_id = o.order_id;

FULL OUTER JOIN is supported in PostgreSQL, SQL Server, and Oracle.

It’s not available in MySQL and SQLite (you’ll need a workaround).

If your database doesn’t support FULL OUTER JOIN, you can simulate it by combining:

orders (with matching payments when available), andpayments that didn’t match an order.One common pattern:

SELECT o.order_id, o.customer_id, p.payment_id, p.amount

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN payments p

ON p.order_id = o.order_id

UNION

SELECT o.order_id, o.customer_id, p.payment_id, p.amount

FROM orders o

RIGHT JOIN payments p

ON p.order_id = o.order_id;

Tip: when you see NULLs on one side, that’s your signal the row was “missing” in the other table — exactly what you want for audits and reconciliation.

A CROSS JOIN returns every possible pairing of rows from two tables. If table A has 3 rows and table B has 4 rows, the result will have 3 × 4 = 12 rows. This is also called a Cartesian product.

That sounds scary—and it can be—but it’s genuinely useful when you want to generate combinations.

Imagine you maintain product options in separate tables:

sizes: S, M, Lcolors: Red, BlueA CROSS JOIN can generate all possible variants (useful for creating SKUs, prebuilding a catalog, or testing):

SELECT

s.size,

c.color

FROM sizes AS s

CROSS JOIN colors AS c;

Result (3 × 2 = 6 rows):

Because row counts multiply, CROSS JOIN can explode quickly:

That can slow queries, overwhelm memory, and produce output nobody can use. If you need combinations, keep the input tables small and consider adding limits or filters in a controlled way.

A SELF JOIN is exactly what it sounds like: you join a table to itself. This is useful when one row in a table relates to another row in the same table—most commonly in “parent/child” relationships like employees and their managers.

Because you’re using the same table twice, you must give each “copy” a different alias. Aliases make the query readable and tell SQL which side you mean.

A common pattern is:

e for the employeem for the managerImagine an employees table like this:

idnamemanager_id (points to another employee’s id)To list each employee with their manager’s name:

SELECT

e.id,

e.name AS employee_name,

m.name AS manager_name

FROM employees e

LEFT JOIN employees m

ON e.manager_id = m.id;

Notice the query uses a LEFT JOIN, not an INNER JOIN. That matters because some employees may have no manager (for example, the CEO). In those cases, manager_id is often NULL, and a LEFT JOIN keeps the employee row while showing manager_name as NULL.

If you used an INNER JOIN instead, those top-level employees would disappear from the results because there’s no matching manager row to join to.

A JOIN doesn’t “magically” know how two tables relate—you have to tell it. That relationship is defined in the join condition, and it belongs right next to the JOIN because it explains how the tables match, not how you want to filter the final results.

ON: the most flexible (and the most common)Use ON when you want full control over the matching logic—different column names, multiple conditions, or extra rules.

SELECT

c.customer_id,

c.name,

o.order_id,

o.created_at

FROM customers AS c

INNER JOIN orders AS o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id;

ON is also where you can define more complex matches (for example, matching on two columns) without turning your query into a guessing game.

USING: shorter, but only for same-name columnsSome databases (like PostgreSQL and MySQL) support USING. It’s a convenient shorthand when both tables have a column with the same name and you want to join on that column.

SELECT

customer_id,

name,

order_id

FROM customers

JOIN orders

USING (customer_id);

One nice benefit: USING typically returns only one customer_id column in the output (instead of two copies).

Once you join tables, column names often overlap (id, created_at, status). If you write SELECT id, the database may throw an “ambiguous column” error—or worse, you might accidentally read the wrong id.

Prefer table prefixes (or aliases) for clarity:

SELECT c.customer_id, o.order_id

FROM customers AS c

JOIN orders AS o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id;

SELECT * in joined queriesSELECT * becomes messy fast with joins: you pull in unnecessary columns, risk duplicate names, and make it harder to see what the query is meant to produce.

Instead, select the exact columns you need. Your result is cleaner, easier to maintain, and often more efficient—especially when tables are wide.

When you join tables, WHERE and ON both “filter,” but they do it at different moments.

That timing difference is the reason people accidentally change a LEFT JOIN into an INNER JOIN.

Say you want all customers, even those with no recent paid orders.

SELECT c.customer_id, c.name, o.order_id, o.status, o.order_date

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id

WHERE o.status = 'PAID'

AND o.order_date >= DATE '2025-01-01';

Problem: for customers with no matching order, o.status and o.order_date are NULL. The WHERE clause rejects those rows, so unmatched customers disappear—your LEFT JOIN behaves like an INNER JOIN.

SELECT c.customer_id, c.name, o.order_id, o.status, o.order_date

FROM customers c

LEFT JOIN orders o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id

AND o.status = 'PAID'

AND o.order_date >= DATE '2025-01-01';

Now customers without qualifying orders still show up (with NULL order columns), which is usually the point of a LEFT JOIN.

WHERE o.order_id IS NOT NULL explicitly).Joins don’t just “add columns”—they can also multiply rows. That’s usually correct behavior, but it often surprises people when totals suddenly double (or worse).

A join returns one output row for every pair of matching rows.

customers to orders, each customer may appear multiple times—once per order.orders to payments and each order can have multiple payments (installments, retries, partial refunds), you can get multiple rows per order. If you also join to another “many” table (like order_items), you can create a multiplication effect: payments × items per order.If your goal is “one row per customer” or “one row per order,” summarize the “many” side first, then join.

-- One row per order from payments

WITH payment_totals AS (

SELECT

order_id,

SUM(amount) AS total_paid,

COUNT(*) AS payment_count

FROM payments

GROUP BY order_id

)

SELECT

o.order_id,

o.customer_id,

COALESCE(pt.total_paid, 0) AS total_paid,

COALESCE(pt.payment_count, 0) AS payment_count

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN payment_totals pt

ON pt.order_id = o.order_id;

This keeps the join “shape” predictable: one order row stays one order row.

SELECT DISTINCT can make duplicates look fixed, but it may hide the real issue:

Use it only when you’re certain duplicates are purely accidental and you understand why they occurred.

Before trusting results, compare row counts:

JOINs are often blamed for “slow queries,” but the real cause is usually how much data you ask the database to combine, and how easily it can find matching rows.

Think of an index like a book’s table of contents. Without it, the database may need to scan many rows to find the matches for your JOIN condition. With an index on the join key (for example, customers.customer_id and orders.customer_id), the database can jump to the relevant rows much faster.

You don’t need to know the internals to use this well: if a column is frequently used to match rows (ON a.id = b.a_id), it’s a good candidate to be indexed.

Whenever possible, join on stable, unique identifiers:

customers.customer_id = orders.customer_idcustomers.email = orders.email or customers.name = orders.nameNames change and can repeat. Emails can change, be missing, or differ by case/format. IDs are designed specifically for consistent matching, and they’re commonly indexed.

Two habits make JOINs noticeably faster:

SELECT * when joining multiple tables—extra columns increase memory and network usage.Example: limit orders first, then join:

SELECT c.customer_id, c.name, o.order_id, o.created_at

FROM customers c

JOIN (

SELECT order_id, customer_id, created_at

FROM orders

WHERE created_at >= DATE '2025-01-01'

) o

ON o.customer_id = c.customer_id;

If you’re iterating on these queries inside an app build (for example, creating a reporting page backed by PostgreSQL), tools like Koder.ai can speed up the scaffolding—schema, endpoints, UI—while you keep control of the JOIN logic that determines correctness.

NULL)NULL when missing)NULLsA SQL JOIN combines rows from two (or more) tables into one result set by matching related columns—most often a primary key to a foreign key (for example, customers.customer_id = orders.customer_id). This is how you “reconnect” normalized tables when you need reports, audits, or analysis.

Use INNER JOIN when you only want rows where the relationship exists in both tables.

It’s ideal for “confirmed relationships,” like listing only customers who actually placed orders.

Use LEFT JOIN when you need all rows from your main (left) table, plus optional matching data from the right.

To find “missing matches,” join and then filter the right side to NULL:

SELECT c.customer_id, c.name

customers c

orders o o.customer_id c.customer_id

o.order_id ;

RIGHT JOIN keeps every row from the right table and fills left-table columns with NULL when there’s no match. Many teams avoid it because it reads “backwards.”

In most cases, you can rewrite it as a LEFT JOIN by swapping table order:

FROM payments p

LEFT JOIN orders o o.order_id p.order_id

Use FULL OUTER JOIN for reconciliation: you want matches, left-only rows, and right-only rows all in one output.

It’s great for audits like “orders without payments” and “payments without orders,” because unmatched sides show up as NULL columns.

Some databases (notably MySQL and SQLite) don’t support FULL OUTER JOIN directly. A common workaround is to combine two queries:

orders LEFT JOIN paymentsTypically this is done with UNION (or UNION ALL plus careful filtering) so you keep both “left-only” and “right-only” records.

A CROSS JOIN returns every combination of rows between two tables (a Cartesian product). It’s useful for generating scenarios (like sizes × colors) or building a calendar grid.

Be careful: row counts multiply quickly, so it can explode output size and slow queries if inputs aren’t small and controlled.

A self join is joining a table to itself to relate rows within the same table (common for hierarchies like employee → manager).

You must use aliases to distinguish the two “copies”:

FROM employees e

LEFT JOIN employees m

ON e.manager_id = m.id

ON defines how rows match during the join; WHERE filters after the join result is formed. With LEFT JOIN, a WHERE condition on the right table can accidentally remove NULL-matched rows and turn it into an effective INNER JOIN.

If you want to keep all left rows but restrict which right rows can match, put the right-table filter in instead.

Joins can multiply rows when the relationship is one-to-many (or many-to-many). For example, an order with two payments will appear twice when you join orders to payments.

To keep “one row per order/customer,” pre-aggregate the many-side first (e.g., SUM(amount) grouped by order_id) and then join. Use DISTINCT only as a last resort because it can hide real join problems and break totals.

ON