Jun 27, 2025·8 min

Adi Shamir’s Breakthroughs: RSA, Secret Sharing, and Security

Explore Adi Shamir’s key ideas behind RSA and secret sharing, and learn how elegant math shapes real-world security, risk, and key handling.

Explore Adi Shamir’s key ideas behind RSA and secret sharing, and learn how elegant math shapes real-world security, risk, and key handling.

Adi Shamir is one of the rare researchers whose ideas didn’t stay confined to papers and conferences—they became the building blocks of everyday security. If you’ve ever used HTTPS, verified a software update, or relied on a digital signature for trust online, you’ve benefited from work he helped shape.

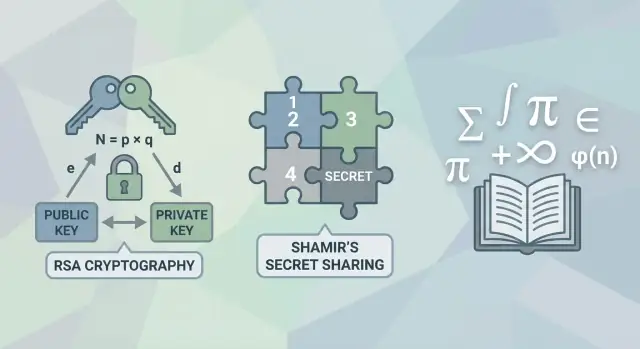

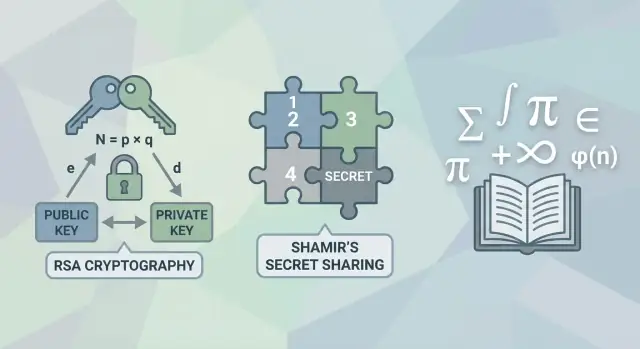

Shamir co-invented RSA, a public-key cryptosystem that made it practical for strangers to exchange secure messages and prove identity at scale. He also created Shamir’s Secret Sharing, a method for splitting a secret (like a cryptographic key) into pieces so that no single person or server has full control.

Both ideas share a theme: a clean mathematical insight can unlock a practical security capability that organizations can actually deploy.

This article focuses on that bridge—from elegant concepts to tools that support real systems. You’ll see how RSA enabled signatures and secure communication, and how secret sharing helps teams spread trust using “k-of-n” rules (for example, any 3 out of 5 key holders can approve a critical action).

We’ll explain the core ideas without heavy equations or advanced number theory. The goal is clarity: understanding what these systems are trying to achieve, why the designs are clever, and where the sharp edges are.

There are limits, though. Strong math doesn’t automatically mean strong security. Real failures often come from implementation mistakes, poor key management, weak operational procedures, or unrealistic assumptions about threats. Shamir’s work helps us see both sides: the power of good cryptographic design—and the necessity of careful, practical execution.

A real cryptographic breakthrough isn’t just “we made encryption faster.” It’s a new capability that changes what people can safely do. Think of it as expanding the set of problems security tools can solve—especially at scale, between strangers, and under real-world constraints like unreliable networks and human mistakes.

Classic “secret codes” focus on hiding a message. Modern cryptography aims broader and more practical:

That shift matters because many failures aren’t about eavesdropping—they’re about tampering, impersonation, and disputes over “who did what.”

With symmetric cryptography, both sides share the same secret key. It’s efficient and still widely used (for example, encrypting large files or network traffic). The hard part is practical: how do two parties securely share that key in the first place—especially if they’ve never met?

Public-key cryptography splits the key into two parts: a public key you can share openly and a private key you keep secret. People can encrypt messages to you using your public key, and only your private key can decrypt them. Or you can sign something with your private key so anyone can verify it with your public key.

When public keys became practical, secure communication stopped requiring a pre-shared secret or a trusted courier. That enabled safer internet-scale systems: secure logins, encrypted web traffic, software updates you can verify, and digital signatures that support identity and accountability.

This is the kind of “new capability” that earns the label breakthrough.

RSA has one of the best origin stories in cryptography: three researchers—Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman—trying to turn a new idea (public-key cryptography) into something you could actually use.

In 1977, they published a scheme that quickly became the most famous practical answer to a simple question: “How can two people communicate securely without first sharing a secret?” Their names became the acronym.

RSA’s big shift is easy to describe in everyday terms. You can publish a lock for anyone to use (your public key), while keeping the only key that opens it to yourself (your private key).

So if someone wants to send you a secret message, they don’t need to meet you first. They take your public lock, snap it on the message, and send the locked box. Only you have the private key that can unlock it.

That “publish the lock, hide the key” promise is why RSA felt magical at the time—and why it became foundational for secure systems.

RSA relies on a special kind of puzzle:

In RSA, the public key lets anyone “mix the paint” to protect a message, while the private key is the hidden recipe that makes unmixing feasible.

RSA shows up in a few key roles:

Even as newer tools have become popular, RSA’s plain-English idea—public lock, private key—still explains a lot about how modern trust on the internet is built.

RSA looks mysterious until you zoom in on two everyday ideas: wrapping numbers around a fixed range and relying on a problem that seems painfully slow to reverse.

Modular arithmetic is what happens when numbers “wrap around,” like hours on a clock. On a 12-hour clock, 10 + 5 doesn’t give 15; it lands on 3.

RSA uses the same wraparound idea, just with a much larger “clock.” You pick a big number (called a modulus) and do calculations where results are always reduced back into the range from 0 up to that modulus minus 1.

Why this matters: modular arithmetic lets you do operations that are easy in one direction, while keeping the reverse direction difficult—exactly the kind of asymmetry cryptography wants.

Cryptography often depends on a task that:

For RSA, the “special information” is the private key. Without it, the attacker faces a problem believed to be extremely expensive.

RSA security is based on the difficulty of factoring: taking a large number and finding the two large prime numbers that were multiplied to create it.

Multiplying two big primes together is straightforward. But if someone hands you only the product and asks for the original primes, that reverse step appears to require enormous effort as the numbers get larger.

This factoring difficulty is the core reason RSA can work: public information is safe to share, while the private key stays practical to use but hard to reconstruct.

RSA isn’t protected by a mathematical proof that factoring is impossible. Instead, it’s protected by decades of evidence: smart researchers have tried many approaches, and the best known methods still take too long at properly chosen sizes.

That’s what “assumed hard” means: not guaranteed forever, but trusted because breaking it efficiently would require a major new discovery.

Key size controls how big that modular “clock” is. Bigger keys generally make factoring dramatically more expensive, pushing attacks beyond realistic time and budget. That’s why older, shorter RSA keys have been retired—and why key length choices are really choices about attacker effort.

Digital signatures answer a different question than encryption. Encryption protects secrecy: “Can only the intended recipient read this?” A signature protects trust: “Who created this, and was it changed?”

A digital signature typically proves two things:

With RSA, the signer uses their private key to produce a short piece of data—the signature—tied to the message. Anyone with the matching public key can check it.

Importantly, you don’t “sign the whole file” directly. In practice, systems sign a hash (a compact fingerprint) of the file. That’s why signing works equally well for a tiny message or a multi‑gigabyte download.

RSA signatures show up anywhere systems need to verify identity at scale:

Naively “doing RSA math” is not enough. Real-world RSA signatures rely on standardized padding and encoding rules (such as those in PKCS#1 or RSA-PSS). Think of these as guardrails that prevent subtle attacks and make signatures unambiguous.

You can encrypt without proving who sent the message, and you can sign without hiding the message. Many secure systems do both—but they solve different problems.

RSA is a strong idea, but most real-world “breaks” don’t defeat the underlying math. They exploit the messy parts around it: how keys are generated, how messages are padded, how devices behave, and how people operate systems.

When headlines say “RSA cracked,” the story is frequently about an implementation mistake or a deployment shortcut. RSA is rarely used as “raw RSA” anymore; it’s embedded in protocols, wrapped in padding schemes, and combined with hashing and randomness. If any of those pieces are wrong, the system can fall even if the core algorithm remains sound.

Here are the kinds of gaps that repeatedly cause incidents:

Modern crypto libraries and standards exist because teams learned these lessons the hard way. They bake in safer defaults, constant-time operations, vetted padding, and protocol-level guardrails. Writing “your own RSA” or tweaking established schemes is risky because small deviations can create brand-new attack paths.

This matters even more when teams are shipping quickly. If you’re using a rapid development workflow—whether it’s a traditional CI/CD pipeline or a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai—the speed advantage only holds if security defaults are also standardized. Koder.ai’s ability to generate and deploy full-stack apps (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile) can shorten the path to production, but you still need disciplined key handling: TLS certificates, secrets management, and release signing should be treated as first-class operational assets, not afterthoughts.

If you want more practical security guidance beyond the math, browse /blog for related guides on implementation and key management.

Relying on one “master secret” is an uncomfortable way to run security. If a single person holds the key (or a single device stores it), you’re exposed to common real-world failures: accidental loss, theft, insider misuse, and even coercion. The secret might be perfectly encrypted, yet still fragile because it has only one owner and one failure point.

Shamir’s Secret Sharing addresses this by splitting one secret into n separate shares and setting a rule that any k shares can rebuild the original secret—while fewer than k reveal nothing useful.

So instead of “Who has the master password?”, the question becomes: “Can we gather k authorized people/devices when we truly need it?”

Threshold security spreads trust across multiple holders:

This is especially valuable for high-impact secrets like recovery keys, certificate authority material, or the root credentials for critical infrastructure.

Shamir’s insight wasn’t just mathematical elegance—it was a practical way to turn trust from a single bet into a measured, auditable rule.

Shamir’s Secret Sharing solves a very practical problem: you don’t want one person, one server, or one USB stick to be “the key.” Instead, you split a secret into pieces so that a group must cooperate to recover it.

Imagine you can draw a smooth curve on graph paper. If you only see one or two points on that curve, you can draw countless different curves that pass through them. But if you see enough points, the curve becomes uniquely determined.

That’s the core idea behind polynomial interpolation: Shamir encodes the secret as part of a curve, then hands out points on that curve. With enough points, you can reconstruct the curve and read the secret back. With too few points, you’re stuck with many possible curves—so the secret stays hidden.

A share is simply one point on that hidden curve: a small bundle of data that looks random by itself.

The scheme is usually described as k-of-n:

Secret sharing only works if shares don’t end up in the same place or under the same control. Good practice is to spread them across people, devices, and locations (for example: one in a hardware token, one with legal counsel, one in a secure vault).

Choosing k is a balancing act:

The elegance is that the math cleanly turns “shared trust” into a precise, enforceable rule.

Secret sharing is best understood as a way to split control, not as a way to “store a secret safely” in the ordinary sense. It’s a governance tool: you deliberately require multiple people (or systems) to cooperate before a key can be reconstructed.

It’s easy to confuse these tools because they all reduce risk, but they reduce different risks.

Secret sharing shines when the “secret” is extremely high value and you want strong checks and balances:

If your main problem is “I might delete files” or “I need to reset user passwords,” secret sharing is usually overkill. It also doesn’t replace good operational security: if an attacker can trick enough share-holders (or compromise their devices), the threshold can be met.

The obvious failure mode is availability: lose too many shares, lose the secret. The subtler risks are human:

Document the process, assign clear roles, and rehearse recovery on a schedule—like a fire drill. A secret-sharing plan that hasn’t been tested is closer to a hope than a control.

RSA and Shamir’s Secret Sharing are famous as “algorithms,” but their real impact shows up when they’re embedded into systems people and organizations actually run: certificate authorities, approval workflows, backups, and incident recovery.

RSA signatures power the idea that a public key can represent an identity. In practice, that becomes PKI: certificates, certificate chains, and policies about who is allowed to sign what. A company isn’t just choosing “RSA vs something else”—it’s choosing who can issue certificates, how often keys rotate, and what happens when a key is suspected to be exposed.

Key rotation is the operational sibling of RSA: you plan for change. Shorter-lived certificates, scheduled replacements, and clear revocation procedures reduce the blast radius of inevitable mistakes.

Secret sharing turns “one key, one owner” into a trust model. You can require k-of-n people (or systems) to reconstruct a recovery secret, approve a sensitive configuration change, or unlock an offline backup. That supports safer recovery: no single admin can quietly take over, and no single lost credential causes permanent lockout.

Good security asks: who can sign releases, who can recover accounts, and who can approve policy changes? Separation of duties reduces both fraud and accidental damage by making high-impact actions require independent agreement.

This is also where operational tooling matters. For example, platforms such as Koder.ai include features like snapshots and rollback, which can reduce the impact of a bad deployment—but those safeguards are most effective when paired with disciplined signing, least-privilege access, and clear “who can approve what” rules.

For teams offering different security tiers—like basic access vs threshold approvals—make the choices explicit (see /pricing).

A cryptographic algorithm can be “secure” on paper and still fail the moment it meets real people, devices, and workflows. Security is always relative: relative to who might attack you, what they can do, what you’re protecting, and what failure would cost.

Start by naming your likely threat actors:

Each actor pushes you toward different defenses. If you worry most about external attackers, you may prioritize hardened servers, secure defaults, and fast patching. If insiders are the bigger risk, you may need separation of duties, audit trails, and approvals.

RSA and secret sharing are great examples of why “good math” is only the starting point.

A practical habit: document your threat model as a short list of assumptions—what you’re protecting, from whom, and what failures you can tolerate. Revisit it when conditions change: new team members, a move to cloud infrastructure, a merger, or a new regulatory requirement.

If you deploy globally, add location and compliance assumptions too: where keys live, where data is processed, and what cross-border constraints apply. (Koder.ai, for example, runs on AWS globally and can deploy applications in different countries to help meet regional privacy and data-transfer requirements—but the responsibility to define the model and configure it correctly still sits with the team.)

Adi Shamir’s work is a reminder of a simple rule: great cryptographic ideas make security possible, but your day-to-day process is what makes it real. RSA and secret sharing are elegant building blocks. The protection you actually get depends on how keys are created, stored, used, rotated, backed up, and recovered.

Think of cryptography as engineering, not magic. An algorithm can be sound while the system around it is fragile—because of rushed deployments, unclear ownership, missing backups, or “temporary” shortcuts that become permanent.

If you want more practical guides on key management and operational security, browse related posts at /blog.

A breakthrough adds a new capability—not just speed. In modern practice that usually means enabling confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity between parties who don’t share a secret in advance, at internet scale.

Symmetric crypto is fast, but it assumes both sides already share the same secret key. Public-key crypto introduces a public key you can share widely and a private key you keep secret, solving the key distribution problem for strangers and large systems.

RSA lets you publish a “lock” (public key) that anyone can use, while only you keep the “key” (private key) to decrypt or sign. It’s widely used for digital signatures, and historically for key transport/exchange in secure protocols.

It relies on modular arithmetic (“clock math”) and the assumption that factoring a very large number (the product of two large primes) is computationally infeasible at proper key sizes. It’s “assumed hard,” not mathematically proven impossible—so parameters and best practices matter.

Encryption answers: “Who can read this?” Signatures answer: “Who created/approved this, and was it changed?” In real systems you usually sign a hash of the data, and verifiers use the public key to check the signature.

Most real failures come from the surrounding system, such as:

Use vetted libraries and standard schemes (e.g., modern padding) instead of “raw RSA.”

Shamir’s Secret Sharing splits one secret into n shares so that any k shares can reconstruct it, while fewer than k reveal nothing useful. It’s a way to replace “one master key holder” with a controlled threshold of cooperating holders.

Use it for high-impact secrets where you want no single point of failure and no single person can act alone, such as:

Avoid it for everyday backups or low-value secrets where the operational overhead outweighs the benefit.

Choose k based on your real-world constraints:

Also ensure shares are separated across people, devices, and locations; otherwise you recreate the single point of failure you meant to remove.

Because security depends on threat models and operations, not just algorithms. Practical steps:

For more implementation guidance, see related posts at /blog.