Aug 17, 2025·8 min

Why AI-Driven Workflows Reduce Premature Abstraction

AI-driven workflows push teams toward concrete steps, fast feedback, and measurable outcomes—reducing the temptation to over-abstract and over-engineer too early.

What We Mean by Premature Abstraction and Over-Engineering

Premature abstraction is when you build a “general solution” before you’ve seen enough real cases to know what should be generalized.

Instead of writing the simplest code that solves today’s problem, you invent a framework: extra interfaces, configuration systems, plug-in points, or reusable modules—because you assume you’ll need them later.

Over-engineering is the broader habit behind it. It’s adding complexity that isn’t currently paying its rent: extra layers, patterns, services, or options that don’t clearly reduce cost or risk right now.

Plain-English examples

If your product has one billing plan and you build a multi-tenant pricing engine “just in case,” that’s premature abstraction.

If a feature could be a single straightforward function, but you split it into six classes with factories and registries to make it “extensible,” that’s over-engineering.

Why it shows up early in projects

These habits are common at the start because early projects are full of uncertainty:

- Fear of rework: Teams worry that if they build something simple, they’ll have to rewrite it later.

- Unclear requirements: When nobody is sure what the product will become, it’s tempting to build a flexible skeleton that can “handle anything.”

- Social pressure: Engineers often want to look ahead and “do it right,” even when “right” isn’t yet knowable.

The problem is that “flexible” often means “harder to change.” Extra layers can make everyday edits slower, debugging harder, and onboarding more painful. You pay the complexity cost immediately, while the benefits might never arrive.

Where AI fits (and where it doesn’t)

AI-driven workflows can encourage teams to keep work concrete—by speeding up prototyping, producing examples quickly, and making it easier to test assumptions. That can reduce the anxiety that fuels speculative design.

But AI doesn’t replace engineering judgment. It can generate clever architectures and abstractions on demand. Your job is still to ask: What’s the simplest thing that works today, and what evidence would justify adding structure tomorrow?

Tools like Koder.ai are especially effective here because they make it easy to go from a chat prompt to a runnable slice of a real app (web, backend, or mobile) quickly—so teams can validate what’s needed before “future-proofing” anything.

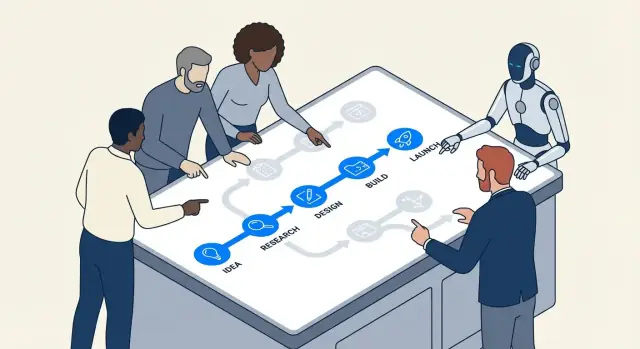

How AI Workflows Nudge Teams Toward Concrete Work

AI-assisted development tends to start with something tangible: a specific bug, a small feature, a data transformation, a UI screen. That framing matters. When the workflow begins with “here’s the exact thing we need,” teams are less likely to invent a generalized architecture before they’ve learned what the problem really is.

Concrete prompts create concrete code

Most AI tools respond best when you provide specifics: inputs, outputs, constraints, and an example. A prompt like “design a flexible notification system” is vague, so the model will often “fill in the blanks” with extra layers—interfaces, factories, configuration—because it can’t see the real boundaries.

But when the prompt is grounded, the output is grounded:

- Input: “Given these order statuses…”

- Output: “Return the user-facing message and CTA…”

- Constraints: “Must be fast; no database call; needs i18n…”

- Examples: “For

PENDING_PAYMENTshow …”

This naturally pushes teams toward implementing a narrow slice that works end-to-end. Once you can run it, review it, and show it, you’re operating in reality rather than speculation.

“Make it work first” becomes the default

AI pair-programming makes iteration cheap. If a first version is slightly messy but correct, the next step is usually “refactor this” rather than “design a system for all future cases.” That sequence—working code first, refinement second—reduces the impulse to build abstractions that haven’t earned their complexity.

In practice, teams end up with a rhythm:

- Ask for a minimal implementation.

- Try it against real examples.

- Adjust based on what breaks or feels awkward.

- Only then extract a helper, module, or pattern.

Specificity exposes missing requirements early

Prompts force you to state what you actually mean. If you can’t define the inputs/outputs clearly, that’s a signal you’re not ready to abstract—you’re still discovering requirements. AI tools reward clarity, so they subtly train teams to clarify first and generalize later.

Short Feedback Loops Reduce Speculative Design

Fast feedback changes what “good engineering” feels like. When you can try an idea in minutes, speculative architecture stops being a comforting safety blanket and starts looking like a cost you can avoid.

The loop: draft → run → inspect → adjust

AI-driven workflows compress the cycle:

- Draft: ask the assistant for a small, working slice (a script, a handler, a query)

- Run: execute it immediately against real inputs

- Inspect: look at outputs, logs, edge cases, and how it fails

- Adjust: refine the code and the requirement at the same time

This loop rewards concrete progress. Instead of debating “we’ll need a plug-in system” or “this must support 12 data sources,” the team sees what the current problem actually demands.

Why speed reduces speculative architecture

Premature abstraction often happens when teams fear change: if changes are expensive, you try to predict the future and design for it. With short loops, change is cheap. That flips the incentive:

- You can defer generalization until repeated work proves it’s needed.

- You discover real constraints (performance, data shape, user behavior) early.

- You stop building “just in case” because you can iterate “just in time.”

A simple example: endpoint before framework

Say you’re adding an internal “export to CSV” feature. The over-engineered path starts with designing a generic export framework, multiple formats, job queues, and configuration layers.

A fast-loop path is smaller: generate a single /exports/orders.csv endpoint (or a one-off script), run it on staging data, and inspect the file size, runtime, and missing fields. If, after two or three exports, you see repeated patterns—same pagination logic, shared filtering, common headers—then an abstraction earns its keep because it’s grounded in evidence, not guesses.

Incremental Changes Make Abstractions Earn Their Keep

Incremental delivery changes the economics of design. When you ship in small slices, every “nice-to-have” layer has to prove it helps right now—not in an imagined future. That’s where AI-driven workflows quietly reduce premature abstraction: AI is great at proposing structures, but those structures are easiest to validate when the scope is small.

Small scope makes AI suggestions testable

If you ask an assistant to refactor a single module or add a new endpoint, you can quickly check whether its abstraction actually improves clarity, reduces duplication, or makes the next change easier. With a small diff, the feedback is immediate: tests pass or fail, the code reads better or worse, and the feature behaves correctly or it doesn’t.

When the scope is large, AI suggestions can feel plausible without being provably useful. You might accept a generalized framework simply because it “looks clean,” only to learn later that it complicates real-world edge cases.

Tiny components reveal what to keep (and what to delete)

Working incrementally encourages building small, disposable components first—helpers, adapters, simple data shapes. Over a few iterations, it becomes obvious which pieces are pulled into multiple features (worth keeping) and which ones were only needed for a one-off experiment (safe to delete).

Abstractions then become a record of actual reuse, not predicted reuse.

Incremental delivery lowers refactor risk

When changes ship continuously, refactoring is less scary. You don’t need to “get it right” upfront because you can evolve the design as evidence accumulates. If a pattern truly earns its keep—reducing repeated work across several increments—promoting it into an abstraction is a low-risk, high-confidence move.

That mindset flips the default: build the simplest version first, then abstract only when the next incremental step clearly benefits from it.

Easy Experimentation Favors Simplicity Over “Big Design”

Make refactors reversible

Refactor confidently with snapshots and rollback when an abstraction adds friction.

AI-driven workflows make experimentation so cheap that “build one grand system” stops being the default. When a team can generate, tweak, and rerun multiple approaches in a single afternoon, it becomes easier to learn what actually works than to predict what might work.

AI makes small variants almost free

Instead of investing days designing a generalized architecture, teams can ask AI to create a few narrow, concrete implementations:

- a straightforward version that handles the happy path well

- a version optimized for readability and maintainability

- a version that adds just one extra capability (e.g., a second input format)

Because creating these variants is fast, the team can explore trade-offs without committing to a “big design” up front. The goal isn’t to ship all variants—it’s to get evidence.

Comparing variants naturally rewards simpler solutions

Once you can place two or three working options side-by-side, complexity becomes visible. The simpler variant often:

- meets the same real requirements

- has fewer moving parts to debug

- makes future changes easier because there’s less hidden coupling

Meanwhile, over-engineered options tend to justify themselves with hypothetical needs. Variant comparison is an antidote to that: if the extra abstraction doesn’t produce clear, near-term benefits, it reads like cost.

Checklist: what to measure when comparing options

When you run lightweight experiments, agree on what “better” means. A practical checklist:

- Time-to-first-working-result: How long until it passes basic scenarios?

- Implementation complexity: Files/modules touched, number of concepts introduced, and how many “rules” a teammate must remember.

- Change cost: How hard is it to add one new requirement (the next likely one, not a far-future fantasy)?

- Failure modes: What breaks, how badly, and how easy it is to detect (clear errors vs silent wrong output).

- Operational risk: New dependencies, configuration surface area, and places where production behavior can drift.

- Testability: How easily you can write a small set of tests that explain the behavior.

If a more abstract variant can’t win on at least one or two of these measures, the simplest working approach is usually the right bet—for now.

AI Helps Clarify Requirements Before You Abstract

Premature abstraction often starts with a sentence like: “We might need this later.” That’s different from: “We need this now.” The first is a guess about future variability; the second is a constraint you can verify today.

AI-driven workflows make that difference harder to ignore because they’re great at turning fuzzy conversations into explicit statements you can inspect.

Turn ambiguity into a written contract (without overcommitting)

When a feature request is vague, teams tend to “future-proof” by building a general framework. Instead, use AI to quickly produce a one-page requirement snapshot that separates what’s real from what’s imagined:

- What we know (current constraints): target users, supported platforms, performance expectations, required integrations.

- What we’re assuming: “Users will have multiple accounts,” “we’ll support 10 locales,” “pricing tiers will exist.”

- What we don’t know yet: edge cases, legal constraints, scale, migration needs.

This simple split changes the engineering conversation. You stop designing for an unknown future and start building for a known present—while keeping a visible list of uncertainties to revisit.

Koder.ai’s Planning Mode fits well here: you can turn a vague request into a concrete plan (steps, data model, endpoints, UI states) before generating implementation—without committing to a sprawling architecture.

A lightweight “future-friendly” approach

You can still leave room to evolve without building a deep abstraction layer. Favor mechanisms that are easy to change or remove:

- Feature flags to ship a narrow version and learn from real usage.

- Configuration for values that vary (timeouts, thresholds, copy) instead of polymorphic systems.

- Small extension points (one interface, one hook, one event) only where variation is already likely.

A good rule: if you can’t name the next two concrete variations, don’t build the framework. Write down the suspected variations as “unknowns,” ship the simplest working path, then let real feedback justify the abstraction later.

If you want to formalize this habit, capture these notes in your PR template or an internal “assumptions” doc linked from the ticket (e.g., /blog/engineering-assumptions-checklist).

Tests and Examples Expose Unnecessary Generalization

A common reason teams over-engineer is that they design for imagined scenarios. Tests and concrete examples flip that: they force you to describe real inputs, real outputs, and real failure modes. Once you’ve written those down, “generic” abstractions often look less useful—and more expensive—than a small, clear implementation.

How AI surfaces edge cases (without inventing architecture)

When you ask an AI assistant to help you write tests, it naturally pushes you toward specificity. Instead of “make it flexible,” you get prompts like: What does this function return when the list is empty? What’s the maximum allowed value? How do we represent an invalid state?

That questioning is valuable because it finds edge cases early, while you’re still deciding what the feature truly needs. If those edge cases are rare or out of scope, you can document them and move on—without building an abstraction “just in case.”

Writing tests first reveals whether an abstraction is needed

Abstractions earn their keep when multiple tests share the same setup or behavior patterns. If your test suite only has one or two concrete scenarios, creating a framework or plugin system is usually a sign you’re optimizing for hypothetical future work.

A simple rule of thumb: if you can’t express at least three distinct behaviors that need the same generalized interface, your abstraction is probably premature.

A mini-template for practical test cases

Use this lightweight structure before reaching for “generalized” design:

- Happy path: Typical input → expected output.

- Boundary: Minimum/maximum values, empty collections, limits (e.g., 0, 1, 1000).

- Failure: Invalid input, missing dependencies, timeouts, permission errors → expected error or fallback behavior.

Once these are written, the code often wants to be straightforward. If repetition appears across several tests, that’s your signal to refactor—not your starting point.

Visible Maintenance Costs Discourage Over-Engineering

Reduce cost while you learn

Share what you build with Koder.ai and earn credits for content or referrals.

Over-engineering often hides behind good intentions: “We’ll need this later.” The problem is that abstractions have ongoing costs that don’t show up in the initial implementation ticket.

The real bill for an abstraction

Every new layer you introduce usually creates recurring work:

- API surface area: more methods, parameters, and edge cases to support (and keep backward compatible).

- Documentation and examples: onboarding others means explaining the abstraction, not just the feature.

- Migrations: once other code depends on a generalized interface, changing it requires adapters, deprecations, and release notes.

- Testing matrix: “generic” code expands scenarios—multiple implementations, more mocks, more integration points.

AI-driven workflows make these costs harder to ignore because they can quickly enumerate what you’re signing up for.

Using AI to estimate complexity: count the moving parts

A practical prompt is: “List the moving parts and dependencies introduced by this design.” A good AI assistant can break the plan into concrete items such as:

- new modules/packages

- public interfaces and versioning expectations

- database schema changes and migration steps

- cross-service calls and failure modes

- new configuration flags, permissions, or queues

Seeing that list side-by-side with a simpler, direct implementation turns “clean architecture” arguments into a clearer tradeoff: do you want to maintain eight new concepts to avoid a duplication you might never have?

A “complexity budget” to keep work honest

One lightweight policy: cap the number of new concepts per feature. For example, allow at most:

- 1 new public API

- 1 new shared abstraction (interface/base class)

- 1 new data model/table

If the feature exceeds the budget, require a justification: which future change is this enabling, and what evidence do you have it’s imminent? Teams that use AI to draft this justification (and to forecast maintenance tasks) tend to choose smaller, reversible steps—because the ongoing costs are visible before the code ships.

When AI Can Push You the Wrong Way (and How to Prevent It)

AI-driven workflows often steer teams toward small, testable steps—but they can also do the opposite. Because AI is great at producing “complete” solutions quickly, it may default to familiar patterns, add extra structure, or generate scaffolding you didn’t ask for. The result can be more code than you need, sooner than you need it.

How AI accidentally encourages over-engineering

A model tends to be rewarded (by human perception) for sounding thorough. That can translate into additional layers, more files, and generalized designs that look professional but don’t solve a real, current problem.

Common warning signs include:

- New abstractions without a concrete use case (e.g., “for future flexibility”)

- Extra layers: service → manager → adapter → factory, when a function would do

- Generic interfaces with only one implementation

- Plugin systems, event buses, or dependency-injection setups introduced early

- A “framework within a framework” created to standardize something you haven’t repeated yet

Mitigations that keep AI output grounded

Treat AI like a fast pair of hands, not an architecture committee. A few constraints go a long way:

- Constrain prompts to the present. Ask for the smallest change that satisfies today’s requirement, and explicitly forbid new patterns unless necessary.

- Require real examples. Before accepting an abstraction, demand 2–3 concrete call sites (or user flows) and ensure the abstraction makes them simpler.

- Limit architecture change per iteration. Allow only one structural change at a time (e.g., “introduce one new module” or “no new layers this PR”).

- Review for deletability. If removing the new layer would barely affect behavior, it’s likely not earned.

If you want a simple rule: don’t let AI generalize until your codebase has repeated pain.

A Practical Decision Framework: Build First, Abstract Later

Get fast feedback loops

Deploy early so real usage, not guesses, decides what deserves abstraction.

AI makes it cheap to generate code, refactor, and try alternatives. That’s a gift—if you use it to delay abstraction until you’ve earned it.

Step 1: Start concrete (optimize for learning)

Begin with the simplest version that solves today’s problem for one “happy path.” Name things directly after what they do (not what they might do later), and keep APIs narrow. If you’re unsure whether a parameter, interface, or plugin system is needed, ship without it.

A helpful rule: prefer duplication over speculation. Duplicated code is visible and easy to delete; speculative generality hides complexity in indirection.

Step 2: Extract later (optimize for stability)

Once the feature is used and changing, refactor with evidence. With AI assistance, you can move fast here: ask it to propose an extraction, but insist on a minimal diff and readable names.

If your tooling supports it, use safety nets that make refactors low-risk. For example, Koder.ai’s snapshots and rollback make it easier to experiment with refactors confidently, because you can revert quickly if the “cleaner” design turns out to be worse in practice.

When abstraction is justified (a quick checklist)

Abstraction earns its keep when most of these are true:

- Repeated logic: the same behavior exists in 2–3 places, and updates have already required multiple edits.

- Proven variability: you’ve seen real variations in production or validated prototypes (not “we might need X someday”).

- Clear ownership: a person/team owns the abstraction, its docs, and its future changes.

- Stable boundary: the input/output shape has stayed consistent across at least a couple iterations.

- Net simplification: the extraction reduces total code and cognitive load, not just reorganizes it.

A simple ritual: the “one week later” review

Add a calendar reminder one week after a feature ships:

- Re-open the diff and list what changed since release.

- Identify any copy-paste edits or recurring bugs.

- Decide one of three outcomes: keep concrete, extract a small helper, or introduce a shared module.

This keeps the default posture: build first, then generalize only when reality forces your hand.

What to Measure to Keep Engineering Lean

Lean engineering isn’t a vibe—it’s something you can observe. AI-driven workflows make it easier to ship small changes quickly, but you still need a few signals to notice when the team is drifting back into speculative design.

A small set of metrics that catch over-engineering early

Track a handful of leading indicators that correlate with unnecessary abstraction:

- Cycle time: time from “work started” to “merged and deployed.” When cycle time grows without a clear increase in scope, it often means extra indirection, extra layers, or “future-proofing.”

- Diff size: average lines changed (or files touched) per change. Big diffs are harder to review and invite generalized solutions.

- Number of concepts introduced: count new modules/services/packages, new interfaces, new configuration knobs, new “framework-y” primitives. Concepts are a tax you pay forever.

- Defect rate: production bugs or support tickets per release. Abstractions can hide edge cases; rising defects after “cleanup” work is a red flag.

- Time-to-onboard: how long it takes a new engineer to ship their first small change. If onboarding slows, the system may be optimizing for elegance over clarity.

You don’t need perfection—trend lines are enough. Review these weekly or per iteration, and ask: “Did we add more concepts than the product required?”

Lightweight documentation that prevents mystery abstractions

Require a short “why this exists” note whenever someone introduces a new abstraction (a new interface, helper layer, internal library, etc.). Keep it to a few lines in the README or as a comment near the entry point:

- What concrete problem did it solve today?

- What alternatives were tried?

- What would justify deleting it?

An action plan to start

Pilot a small AI-assisted workflow for one team for 2–4 weeks: AI-supported ticket breakdown, AI-assisted code review checklists, and AI-generated test cases.

At the end, compare the metrics above and do a short retro: keep what reduced cycle time and onboarding friction; roll back anything that increased “concepts introduced” without measurable product benefit.

If you’re looking for a practical environment to run this experiment end-to-end, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you turn those small, concrete slices into deployable apps quickly (with source export available when you need it), which reinforces the habit this article argues for: ship something real, learn, and only then abstract.