Sep 15, 2025·8 min

Why AI-Generated Codebases Can Be Easier to Rewrite

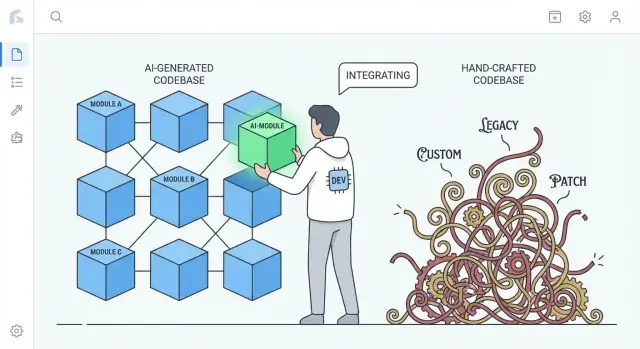

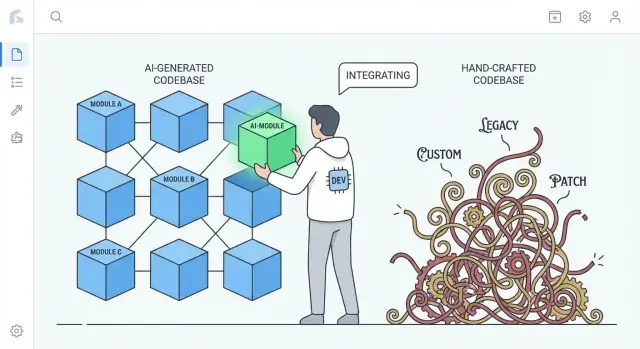

AI-generated codebases often follow repeatable patterns, making rewrites and replacements simpler than bespoke hand-crafted systems. Here’s why—and how to use it safely.

AI-generated codebases often follow repeatable patterns, making rewrites and replacements simpler than bespoke hand-crafted systems. Here’s why—and how to use it safely.

“Easier to replace” rarely means deleting an entire application and starting over. In real teams, replacement happens at different scales, and what “rewrite” means depends on what you’re swapping out.

A replacement might be:

When people say a codebase is “easier to rewrite,” they usually mean you can restart one slice without unraveling everything else, keep the business running, and migrate gradually.

This argument isn’t “AI code is better.” It’s about common tendencies.

That difference matters during a rewrite: code that follows widely understood conventions can often be replaced by another conventional implementation with less negotiation and fewer surprises.

AI-generated code can be inconsistent, repetitive, or under-tested. “Easier to replace” is not a claim that it’s cleaner—it’s a claim that it’s often less “special.” If a subsystem is built from common ingredients, swapping it out can be more like replacing a standard part than reverse-engineering a custom machine.

The core idea is simple: standardization lowers switching costs. When code is composed of recognizable patterns and clear seams, you can regenerate, refactor, or rewrite pieces with less fear of breaking hidden dependencies. The sections below show how that plays out in structure, ownership, testing, and day-to-day engineering velocity.

A practical upside of AI-generated code is that it often defaults to common, recognizable patterns: familiar folder layouts, predictable naming, mainstream framework conventions, and “textbook” approaches to routing, validation, error handling, and data access. Even when the code isn’t perfect, it’s usually legible in the same way many tutorials and starter projects are legible.

Rewrites are expensive largely because people must first understand what exists. Code that follows well-known conventions reduces that “decoding” time. New engineers can map what they see to mental models they already have: where configuration lives, how requests flow, how dependencies are wired, and where tests should go.

This makes it faster to:

By contrast, highly handcrafted codebases often reflect a deeply personal style: unique abstractions, custom mini-frameworks, clever “glue” code, or domain-specific patterns that only make sense with historical context. Those choices can be elegant—but they increase the cost of starting over because a rewrite must first re-learn the author’s worldview.

This isn’t magic exclusive to AI. Teams can (and should) enforce structure and style using templates, linters, formatters, and scaffolding tools. The difference is that AI tends to produce “generic by default,” while human-written systems sometimes drift toward bespoke solutions unless conventions are actively maintained.

A lot of rewrite pain isn’t caused by the “main” business logic. It’s caused by bespoke glue—custom helpers, homegrown micro-frameworks, metaprogramming tricks, and one-off conventions that quietly connect everything together.

Bespoke glue is the stuff that isn’t part of your product, yet your product can’t function without it. Examples include: a custom dependency injection container, a DIY routing layer, a magical base class that auto-registers models, or helpers that mutate global state “for convenience.” It often starts as a time-saver and ends up as required knowledge for every change.

The problem isn’t that glue exists—it’s that it becomes invisible coupling. When glue is unique to your team, it often:

During a rewrite, this glue is hard to replicate correctly because the rules are rarely written down. You discover them by breaking production.

AI outputs often lean toward standard libraries, common patterns, and explicit wiring. It may not invent a micro-framework when a straightforward module or service object will do. That restraint can be a feature: fewer magical hooks means fewer hidden dependencies, and that makes it easier to rip out a subsystem and replace it.

The downside is that “plain” code can be more verbose—more parameters passed around, more straightforward plumbing, fewer shortcuts. But verbosity is usually cheaper than mystery. When you decide to rewrite, you want code that is easy to understand, easy to delete, and hard to misinterpret.

“Predictable structure” is less about beauty and more about consistency: the same folders, naming rules, and request flows show up everywhere. AI-generated projects often lean toward familiar defaults—controllers/, services/, repositories/, models/—with repetitive CRUD endpoints and similar validation patterns.

That uniformity matters because it turns a rewrite from a cliff into a staircase.

You see patterns repeated across features:

UserService, UserRepository, UserController)When every feature is built the same way, you can replace one piece without having to “re-learn” the system each time.

Incremental rewrites work best when you can isolate a boundary and rebuild behind it. Predictable structures naturally create those seams: each layer has a narrow job, and most calls go through a small set of interfaces.

A practical approach is the “strangler” style: keep the public API stable, and replace internals gradually.

Suppose your app has controllers calling a service, and the service calls a repository:

OrdersController → OrdersService → OrdersRepositoryYou want to move from direct SQL queries to an ORM, or from one database to another. In a predictable codebase, the change can be contained:

OrdersRepositoryV2 (new implementation)getOrder(id), listOrders(filters))The controller and service code stays mostly untouched.

Highly hand-crafted systems can be excellent—but they often encode unique ideas: custom abstractions, clever metaprogramming, or cross-cutting behavior hidden in base classes. That can make each change require deep historical context. With predictable structure, the “where do I change this?” question is usually straightforward, which makes small rewrites feasible week after week.

A quiet blocker in many rewrites isn’t technical—it’s social. Teams often carry ownership risk, where only one person truly understands how the system works. When that person wrote big chunks of the code by hand, the code can start to feel like a personal artifact: “my design,” “my clever solution,” “my workaround that saved the release.” That attachment makes deletion emotionally expensive, even when it’s economically rational.

AI-generated code can reduce that effect. Because the initial draft may be produced by a tool (and often follows familiar patterns), the code feels less like a signature and more like an interchangeable implementation. People are typically more comfortable saying, “Let’s replace this module,” when it doesn’t feel like erasing someone’s craftsmanship—or challenging their status on the team.

When author attachment is lower, teams tend to:

Rewrite decisions should still be driven by cost and outcomes: delivery timelines, risk, maintainability, and user impact. “It’s easy to delete” is a helpful property—not a strategy on its own.

One underrated benefit of AI-generated code is that the inputs to generation can act like a living specification. A prompt, a template, and a generator configuration can describe intent in plain language: what the feature should do, which constraints matter (security, performance, style), and what “done” looks like.

When teams use repeatable prompts (or prompt libraries) and stable templates, they create an audit trail of decisions that would otherwise be implicit. A good prompt might state things a future maintainer typically has to guess:

That’s meaningfully different from many hand-crafted codebases, where key design choices are scattered across commit messages, tribal knowledge, and small, unwritten conventions.

If you keep generation traces (the prompt + model/version + inputs + post-processing steps), a rewrite doesn’t start from a blank page. You can reuse the same checklist to recreate the same behavior under a cleaner structure, then compare outputs.

In practice, this can turn a rewrite into: “regenerate feature X under new conventions, then verify parity,” rather than, “reverse-engineer what feature X was supposed to do.”

This only works if prompts and configs are managed with the same discipline as source code:

Without that, prompts become another undocumented dependency. With it, they can be the documentation that hand-built systems often wish they had.

“Easier to replace” isn’t really about whether code was written by a person or an assistant. It’s about whether you can change it with confidence. A rewrite becomes routine engineering when tests tell you, quickly and reliably, that the behavior stayed the same.

AI-generated code can help here—when you ask for it. Many teams prompt for boilerplate tests alongside features (basic unit tests, happy-path integration tests, simple mocks). Those tests may not be perfect, but they create an initial safety net that’s often missing in hand-built systems where tests were deferred “until later.”

If you want replaceability, focus testing energy on the seams where parts meet:

Contract tests lock down what must remain true even if you swap out the internals. That means you can rewrite a module behind an API or replace an adapter implementation without re-litigating business behavior.

Coverage numbers can guide where your risks are, but chasing 100% often produces fragile tests that block refactors. Instead:

With strong tests in place, rewrites stop being heroic projects and become a series of safe, reversible steps.

AI-generated code tends to fail in predictable ways. You’ll often see duplicated logic (the same helper reimplemented three times), “almost the same” branches that handle edge cases differently, or functions that grow by accretion as the model keeps appending fixes. None of that is ideal—but it has one upside: the problems are usually visible.

Hand-crafted systems can hide complexity behind clever abstractions, micro-optimizations, or tightly coupled “just-so” behavior. Those bugs are painful because they look correct and pass casual review.

AI code is more likely to be plainly inconsistent: a parameter is ignored in one path, a validation check exists in one file but not another, or error handling changes style every few functions. These mismatches stand out during review and static analysis, and they’re easier to isolate because they rarely depend on deep, intentional invariants.

Repetition is the tell. When you see the same sequence of steps reappear—parse input → normalize → validate → map → return—across endpoints or services, you’ve found a natural seam for replacement. AI often “solves” a new request by reprinting a previous solution with tweaks, which creates clusters of near-duplicates.

A practical approach is to mark any repeated chunk as a candidate for extraction or replacement, especially when:

If you can name the repeated behavior in a sentence, it should probably be a single module.

Replace the repeated chunks with one well-tested component (a utility, shared service, or library function), write tests that pin down the expected edge cases, and then delete the duplicates. You’ve turned many fragile copies into one place to improve—and one place to rewrite later if needed.

AI-generated code often shines when you ask it to optimize for clarity instead of cleverness. Given the right prompts and linting rules, it will usually choose familiar control flow, conventional naming, and “boring” modules over novelty. That can be a bigger long-term win than a few percent of speed gained from hand-tuned tricks.

Rewrites succeed when new people can quickly build a correct mental model of the system. Readable, consistent code lowers the time it takes to answer basic questions like “Where does this request enter?” and “What shape does this data have here?” If every service follows similar patterns (layout, error handling, logging, configuration), a new team can replace one slice at a time without constantly re-learning local conventions.

Consistency also reduces fear. When code is predictable, engineers can delete and rebuild parts with confidence because the surface area is easier to understand and the “blast radius” feels smaller.

Highly optimized, hand-crafted code can be hard to rewrite because performance techniques often leak everywhere: custom caching layers, micro-optimizations, homegrown concurrency patterns, or tight coupling to specific data structures. These choices may be valid, but they frequently create subtle constraints that aren’t obvious until something breaks.

Readability is not a license to be slow. The point is to earn performance with evidence. Before a rewrite, capture baseline metrics (latency percentiles, CPU, memory, cost). After replacing a component, measure again. If performance regresses, optimize the specific hot path—without turning the whole codebase into a puzzle.

When an AI-assisted codebase starts to feel “off,” you don’t automatically need a full rewrite. The best reset depends on how much of the system is wrong versus merely messy.

Regenerate means re-creating a part of the code from a spec or prompt—often starting from a template or a known pattern—then reapplying integration points (routes, contracts, tests). It’s not “delete everything,” it’s “rebuild this slice from a clearer description.”

Refactor keeps behavior the same but changes internal structure: rename, split modules, simplify conditionals, remove duplication, improve tests.

Rewrite replaces a component or system with a new implementation, usually because the current design can’t be made healthy without changing behavior, boundaries, or data flows.

Regeneration shines when the code is mostly boilerplate and the value lives in interfaces rather than clever internals:

If the spec is clear and the module boundary is clean, regenerating is often faster than untangling incremental edits.

Be cautious when the code encodes hard-won domain knowledge or subtle correctness constraints:

In these areas, “close enough” can be wrong in expensive ways—regeneration may still help, but only if you can prove equivalence with strong tests and reviews.

Treat regenerated code like a new dependency: require human review, run the full test suite, and add targeted tests for failures you’ve seen before. Roll out in small slices—one endpoint, one screen, one adapter—behind a feature flag or gradual release if possible.

A useful default is: regenerate the shell, refactor the seams, rewrite only the parts where assumptions keep breaking.

“Easy to replace” only stays a benefit if teams treat replacement as an engineered activity, not a casual reset button. AI-written modules can be swapped faster—but they can also fail faster if you trust them more than you verify them.

AI-generated code often looks complete even when it isn’t. That can create false confidence, especially when happy-path demos pass.

A second risk is missing edge cases: unusual inputs, timeouts, concurrency quirks, and error handling that weren’t covered in the prompt or sample data.

Finally, there’s licensing/IP uncertainty. Even if risk is low in many setups, teams should have a policy for what sources and tools are acceptable, and how provenance is tracked.

Put replacement behind the same gates as any other change:

Before replacing a component, write down its boundary and invariants: what inputs it accepts, what it guarantees, what it must never do (e.g., “never delete customer data”), and performance/latency expectations. This “contract” is what you test against—regardless of who (or what) writes the code.

AI-generated code is often easier to rewrite because it tends to follow familiar patterns, avoids deep “craft” personalization, and is quicker to regenerate when requirements change. That predictability reduces the social and technical cost of deleting and replacing parts of the system.

The goal isn’t “throw code away,” but to make replacing code a normal, low-friction option—backed by contracts and tests.

Start by standardizing conventions so any regenerated or rewritten code fits the same mold:

If you’re using a vibe-coding workflow, look for tooling that makes those practices easy: saving “planning mode” specs alongside the repo, capturing generation traces, and supporting safe rollback. For example, Koder.ai is designed around chat-driven generation with snapshots and rollback, which fits well with a “replaceable by design” approach—regenerate a slice, keep the contract stable, and revert quickly if parity tests fail.

Pick one module that’s important but safely isolated—report generation, notification sending, or a single CRUD area. Define its public interface, add contract tests, then allow yourself to regenerate/refactor/rewrite the internals until it’s boring. Measure cycle time, defect rate, and review effort; use the results to set team-wide rules.

To operationalize this, keep a checklist in your internal playbook (or share it via /blog) and make the “contracts + conventions + traces” trio a requirement for new work. If you’re evaluating tooling support, you can also document what you’d need from a solution before looking at /pricing.

“Replace” usually means swapping a slice of the system while the rest keeps running. Common targets are:

Full “delete and rewrite the whole app” is rare; most successful rewrites are incremental.

The claim is about typical tendencies, not quality. AI-generated code often:

That “less special” shape is often faster to understand and therefore faster to swap out safely.

Standard patterns lower the “decoding cost” during a rewrite. If engineers can quickly recognize:

…they can reproduce behavior in a new implementation without first learning a private architecture.

Custom glue (homegrown DI containers, magical base classes, implicit global state) creates coupling that isn’t obvious in the code. During replacement you end up:

More explicit, conventional wiring tends to reduce those surprises.

A practical approach is to stabilize the boundary and swap the internals:

This is the “strangler” style: staircase, not cliff.

Because the code feels less like a personal artifact, teams are often more willing to:

It doesn’t remove engineering judgment, but it can reduce social friction around change.

If you keep prompts, templates, and generation configs in the repo, they can act like a lightweight spec:

Version them like code and record which prompt/config produced which module, otherwise prompts become another undocumented dependency.

Focus tests on seams where replacements happen:

When those contract tests pass, you can rewrite internals with far less fear.

AI-generated code often fails in visible ways:

Use repetition as a signal: extract or replace repeated chunks into one tested module, then delete the copies.

Use regeneration for boilerplate-y slices with clear interfaces; refactor for structural cleanup; rewrite when the architecture/boundaries are wrong.

As guardrails, keep a lightweight checklist:

This keeps “easy to replace” from turning into “easy to break.”