Nov 16, 2025·8 min

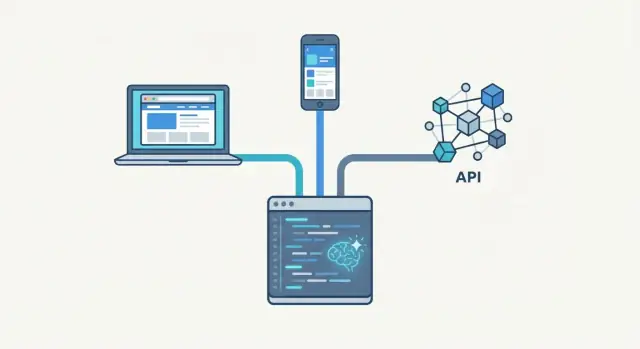

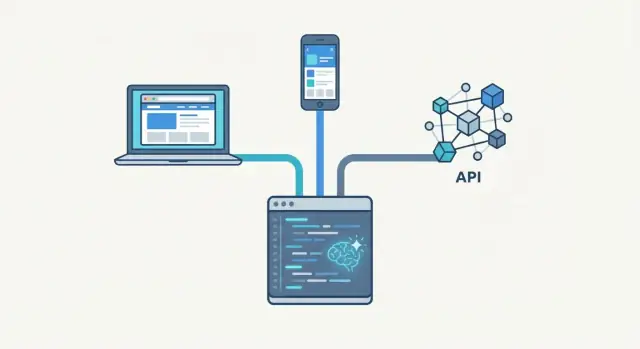

How AI Lets One Codebase Ship Web Apps, Mobile Apps, and APIs

Learn how AI helps teams maintain one codebase that ships a web app, mobile app, and APIs together—covering architecture, automation, testing, and pitfalls.

Learn how AI helps teams maintain one codebase that ships a web app, mobile app, and APIs together—covering architecture, automation, testing, and pitfalls.

“One codebase” doesn’t mean every screen looks the same or every platform uses the exact same UI framework. It means there is a single, versioned source of truth for the product’s behavior—so Web, Mobile, and the API are built from the same core rules, released from the same repo boundaries, and tested against the same contracts.

One codebase: one place to change business rules (pricing, permissions, validation, workflows) and have those changes flow to all outputs. Platform-specific parts still exist, but they sit around the shared core.

Shared libraries: multiple apps with a common package, but each app can drift—different versions, different assumptions, inconsistent releases.

Copy‑paste reuse: fastest at first, then expensive. Fixes and improvements don’t propagate reliably, and bugs get duplicated.

Most teams don’t chase one codebase for ideology. They want fewer “Web says X, mobile says Y” incidents, fewer late-breaking API changes, and predictable releases. When one feature ships, all clients get the same rules and the API reflects the same decisions.

AI helps by generating boilerplate, wiring models to endpoints, drafting tests, and refactoring repeated patterns into shared modules. It can also flag inconsistencies (e.g., validation differs between clients) and speed up documentation.

Humans still define product intent, data contracts, security rules, edge cases, and the review process. AI can accelerate decisions; it can’t replace them.

A small team might share logic and API schemas first, leaving UI mostly platform-native. Larger teams usually add stricter boundaries, shared testing, and release automation earlier to keep many contributors aligned.

Most teams don’t start out aiming for “one codebase.” They get there after living through the pain of maintaining three separate products that are supposed to behave like one.

When web, mobile, and backend live in different repos (often owned by different sub-teams), the same work gets repeated in slightly different ways. A bug fix turns into three bug fixes. A small policy change—like how discounts apply, how dates are rounded, or which fields are required—has to be re-implemented and re-tested multiple times.

Over time, codebases drift. Edge cases get handled “just this once” on one platform. Meanwhile another platform still runs the old rule—because nobody realized it existed, because it was never documented, or because rewriting it was too risky close to a release.

Feature parity rarely breaks because people don’t care. It breaks because each platform has its own release cadence and constraints. Web can ship daily, mobile waits on app store review, and API changes may need careful versioning.

Users notice immediately:

APIs often trail UI changes because teams build the fastest path to ship a screen, then circle back to “proper endpoints later.” Sometimes it flips: backend ships a new model, but UI teams don’t update in lockstep, so the API exposes capabilities that no client uses correctly.

More repos mean more coordination overhead: more pull requests, more QA cycles, more release notes, more on-call context switching, and more chances for something to go out of sync.

A “one codebase” setup works best when you separate what your product does from how each platform delivers it. The simplest mental model is a shared core that contains the rules of the business, plus thin platform shells for web, mobile, and the API.

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ Domain/Core │

│ entities • rules • workflows │

│ validation • permissions │

└───────────────┬───────────────┘

│ contracts

│ (types/interfaces/schemas)

┌───────────────┼───────────────┐

│ │ │

┌────────▼────────┐ ┌────▼─────────┐ ┌───▼──────────┐

│ Web Shell │ │ Mobile Shell │ │ API Delivery │

│ routing, UI │ │ screens, nav │ │ HTTP, auth │

│ browser storage │ │ device perms │ │ versioning │

└──────────────────┘ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘

The core is where you put things like “how totals are calculated,” “who can approve a request,” and “what counts as valid input.” The shells translate that into platform-specific experiences.

Mobile will still need device integrations such as camera access, push notifications, deep links, biometric unlock, and offline storage policies. Web will still have browser-only concerns like cookies, URL routing, responsive layouts, and accessibility patterns. The API layer still owns HTTP specifics: status codes, pagination, rate limits, and auth flows.

The glue is explicit contracts: shared types, interfaces, and schemas (for example, request/response models and validation rules). When the shells must talk to the core through these contracts, teams argue less about “which platform is right,” because the source of truth is the shared behavior—each platform simply renders it.

This structure keeps the shared part stable, while letting each platform move fast where it’s genuinely different.

When people say “one codebase,” the biggest win usually isn’t the UI—it’s having a single source of truth for how the business works. That means your models, rules, and validation live in one shared place, and every client (web, mobile, and API) relies on them.

A shared core typically contains:

When these rules sit in one module, you avoid the classic drift: web shows one total, mobile shows another, and the API enforces something else.

AI app development tools are especially useful when you already have duplication. They can:

The key is to treat AI suggestions as drafts: you still review boundaries, add tests, and confirm behavior against real scenarios.

Sharing business logic is high-leverage; sharing UI code often isn’t. Each platform has different navigation patterns, accessibility expectations, and performance constraints.

Keep the shared core focused on decisions and data, while platform shells handle presentation, device features, and UX. This avoids a “one-size-fits-none” interface while still keeping behavior consistent everywhere.

An “API-first” approach means you design and agree on the API contract before building any specific UI. Instead of the web app setting the rules and mobile “catching up,” every client (web, iOS/Android, internal tools) consumes the same intentional interface.

This helps multi-platform teams because decisions about data shape, error handling, pagination, and authentication happen once—then each platform can move independently without reinventing business rules.

Schemas turn your API into something precise and testable. With OpenAPI (REST) or a GraphQL schema, you can:

When the schema changes, you can detect breaking changes in CI before any app release goes out.

AI is most useful when it works from your existing schema, domain terms, and examples. It can draft:

The key is review: treat AI output as a starting point, then enforce the schema with linters and contract tests.

AI is most useful in a “one codebase” setup when it accelerates the boring parts—then gets out of the way. Think of it as scaffolding: it can generate a first draft quickly, but your team still owns the structure, naming, and boundaries.

Platforms like Koder.ai are designed for this workflow: you can vibe-code from a spec in chat, generate a React web app, a Go + PostgreSQL backend, and a Flutter mobile app, then export and own the source code so it still behaves like a normal, maintainable repo.

The goal isn’t to accept a big, opaque framework dump. The goal is to generate small, readable modules that match your existing architecture (shared core + platform shells), so you can edit, test, and refactor like normal. If the output is plain code in your repo (not a hidden runtime), you’re not locked in—you can replace pieces over time.

For shared code and client shells, AI can reliably draft:

It won’t make hard product decisions for you, but it will save hours on repetitive wiring.

AI outputs improve dramatically when you give concrete constraints:

A good prompt reads like a mini spec plus a skeleton of your architecture.

Treat generated code like junior-dev code: helpful, but needs checks.

Used this way, AI speeds up delivery while keeping your codebase maintainable.

A “one codebase” UI strategy works best when you aim for consistent patterns, not identical pixels. Users expect the same product to feel familiar across devices, while still respecting what each platform is good at.

Start by defining reusable UI patterns that travel well: navigation structure, empty states, loading skeletons, error handling, forms, and content hierarchy. These can be shared as components and guidelines.

Then allow platform-native differences where they matter:

The goal: users recognize the product instantly, even if a screen is laid out differently.

Design tokens turn branding consistency into code: colors, typography, spacing, elevation, and motion become named values rather than hard-coded numbers.

With tokens, you can maintain one brand while still supporting:

AI is useful as a fast assistant for the last-mile work:

Keep a human-approved design system as the source of truth, and use AI to speed up implementation and review.

Mobile isn’t just “smaller web.” Plan explicitly for offline mode, intermittent connectivity, and backgrounding. Design touch targets for thumbs, simplify dense tables, and prioritize the most important actions at the top. When you do this, consistency becomes a user benefit—not a constraint.

A “monorepo” simply means you keep multiple related projects (web app, mobile app, API, shared libraries) in one repository. Instead of hunting across separate repos to update a feature end-to-end, you can change the shared logic and the clients in one pull request.

A monorepo is most useful when the same feature touches more than one output—like changing pricing rules that affect the API response, the mobile checkout, and the web UI. It also makes it easier to keep versions aligned: the web app can’t accidentally depend on “v3” of a shared package while mobile is still on “v2”.

That said, monorepos need discipline. Without clear boundaries, they can turn into a place where every team edits everything.

A practical structure is “apps” plus “packages”:

AI can help here by generating consistent package templates (README, exports, tests), and by updating imports and public APIs when packages evolve.

Set a rule that dependencies point inward, not sideways. For example:

Enforce this with tooling (lint rules, workspace constraints) and code review checklists. The goal is simple: shared packages stay truly reusable, and app-specific code stays local.

If your teams are large, have different release cycles, or strict access controls, multiple repos can work. You can still publish shared packages (core logic, UI kit, API client) to an internal registry and version them. The trade-off is more coordination: you’ll spend extra effort managing releases, updates, and compatibility across repos.

When one codebase produces a web app, a mobile app, and an API, testing stops being “nice to have.” A single regression can surface in three places, and it’s rarely obvious where the break started. The goal is to build a test stack that catches issues close to the source and proves each output still behaves correctly.

Start by treating shared code as the highest-leverage place to test.

AI is most useful when you give it context and constraints. Provide the function signature, expected behavior, and known failure modes, then ask it for:

You still review the tests, but AI helps you avoid missing boring-but-dangerous cases.

When your API changes, web and mobile break silently. Add contract testing (e.g., OpenAPI schema checks, consumer-driven contracts) so the API can’t ship if it violates what clients rely on.

Adopt a rule: no generated code merges without tests. If AI creates a handler, model, or shared function, the PR must include at least unit coverage (and a contract update when the API shape changes).

Shipping from “one codebase” doesn’t mean you press one button and magically get perfect web, mobile, and API releases. It means you design a single pipeline that produces three artifacts from the same commit, with clear rules about what must move together (shared logic, API contracts) and what can move independently (app store rollout timing).

A practical approach is a single CI workflow triggered on every merge to your main branch. That workflow:

AI helps here by generating consistent build scripts, updating version files, and keeping repetitive wiring (like package boundaries and build steps) in sync—especially when new modules are added. If you’re using a platform such as Koder.ai, snapshots and rollback features can also complement your CI pipeline by giving you a quick way to revert application state while you diagnose a bad change.

Treat environments as configuration, not branches. Keep the same code moving through dev, staging, and production with environment-specific settings injected at deploy time:

A common pattern is: ephemeral preview environments per pull request, a shared staging that mirrors production, and production behind phased rollouts. If you need setup guides for your team, point them to /docs; if you’re comparing CI options or plans, /pricing can be a helpful reference.

To “ship together” without blocking on app store review, use feature flags to coordinate behavior across clients. For example, you can deploy an API that supports a new field while keeping it hidden behind a flag until web and mobile are ready.

For mobile, use phased rollouts (e.g., 1% → 10% → 50% → 100%) and monitor crashes and key flows. For web and API, canary deployments or small-percentage traffic splitting serve the same purpose.

Rollbacks should be boring:

The goal is simple: any single commit should be traceable to the exact web build, mobile build, and API version, so you can roll forward or roll back with confidence.

Shipping web, mobile, and APIs from one codebase is powerful—but the failure modes are predictable. The goal isn’t “share everything,” it’s “share the right things” with clear boundaries.

Over-sharing is the #1 mistake. Teams push UI code, storage adapters, or platform-specific quirks into the shared core because it feels faster.

A few patterns to watch for:

AI can generate a lot of reusable code quickly, but it can also standardize bad decisions.

Most teams can’t pause delivery to “go all-in” on one codebase. The safest approach is incremental: share what’s stable first, keep platform autonomy where it matters, and use AI to reduce the cost of refactoring.

1) Audit duplication and pick the first shared slice. Look for code that already should match everywhere: data models, validation rules, error codes, and permission checks. This is your low-risk starting point.

2) Create one shared module: models + validation. Extract schemas (types), validation, and serialization into a shared package. Keep platform-specific adapters thin (e.g., mapping form fields to shared validators). This immediately reduces “same bug three times” problems.

3) Add a contract test suite for the API surface. Before touching UI, lock down behavior with tests that run against the API and shared validators. This gives you a safety net for future consolidation.

4) Move business logic next, not UI. Refactor core workflows (pricing rules, onboarding steps, syncing rules) into shared functions/services. Web and mobile call the shared core; the API uses the same logic server-side.

5) Consolidate UI selectively. Only share UI components when they’re truly identical (buttons, formatting, design tokens). Allow different screens where platform conventions differ.

Use AI to keep changes small and reviewable:

If you’re doing this inside a tooling layer like Koder.ai, planning mode can be a practical way to turn these steps into an explicit checklist before code is generated or moved—making the refactor easier to review and less likely to blur boundaries.

Set measurable checkpoints:

Track progress with practical metrics:

It means there’s a single, versioned source of truth for product behavior (rules, workflows, validation, permissions) that all outputs rely on.

UI and platform integrations can still be different; what’s shared is the decision-making and contracts so Web, Mobile, and the API stay consistent.

Shared libraries are reusable packages, but each app can drift by pinning different versions, making different assumptions, or releasing on different schedules.

A true “one codebase” approach makes changes to core behavior flow to every output from the same source and the same contracts.

Because platforms ship on different cadences. Web can deploy daily, mobile may wait on app store review, and the API may need careful versioning.

A shared core plus contracts reduces “Web says X, mobile says Y” by making the rule itself the shared artifact—not three separate re-implementations.

Put business logic in the shared core:

Keep platform shells responsible for UI, navigation, storage, and device/browser specifics.

Use explicit, testable contracts such as shared types/interfaces and API schemas (OpenAPI or GraphQL).

Then enforce them in CI (schema validation, breaking-change checks, contract tests) so a change can’t ship if it violates what clients expect.

Design the API contract intentionally before building a specific UI, so all clients consume the same interface.

Practically, that means agreeing on request/response shapes, error formats, pagination, and auth once—then generating typed clients and keeping docs and validation aligned with the schema.

AI is strongest at accelerating repetitive work:

You still need humans to own intent, edge cases, and review, and to enforce guardrails before merging.

A monorepo helps when a single change touches shared logic plus web/mobile/API, because you can update everything in one pull request and keep versions aligned.

If you can’t use a monorepo (access controls, independent release cycles), multiple repos can still work—expect more coordination around package versioning and compatibility.

Prioritize tests closest to the shared source of truth:

Add contract tests so API changes can’t silently break web or mobile.

Common pitfalls include over-sharing (platform hacks leaking into core), accidental coupling (core importing UI/HTTP), and inconsistent assumptions (offline vs. always-online).

Guardrails that help: