Jun 27, 2025·8 min

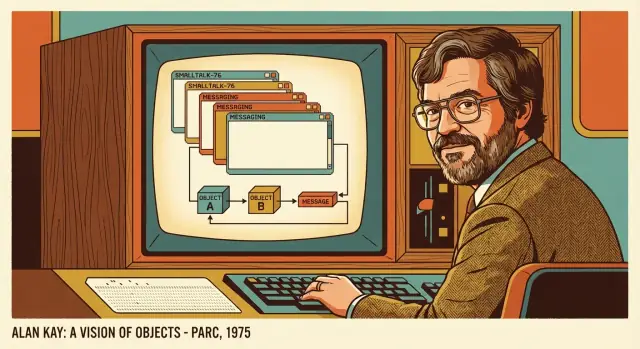

Alan Kay’s Big Ideas: Smalltalk, GUIs, and Software Systems

Explore Alan Kay’s key ideas behind Smalltalk and early GUIs—and how they shaped today’s view of software as interacting systems of objects.

Why Alan Kay Still Matters to Everyday Software

Alan Kay isn’t just a name from programming history. Many everyday assumptions we carry about computers—what a “window” is, why software should be interactive, how programs can be built from cooperating parts—were shaped by ideas he pushed forward (often with teams at Xerox PARC).

This post is about concepts, not trivia. You don’t need to know how to code to follow it, and you won’t find a tour of obscure technical details. Instead, we’ll focus on a few mental models that still show up in the tools and products we use: how software can be understood, changed, and learned.

Three themes we’ll keep returning to

First, Smalltalk: not only a programming language, but an entire working environment that encouraged exploration and learning.

Second, GUIs (graphical user interfaces): windows, icons, menus—interactive software as something you can directly manipulate, not just instruct.

Third, systems thinking: viewing software as a set of interacting parts with feedback loops, rather than a pile of code files.

What this post won’t do

It won’t treat Kay as a lone genius, and it won’t claim that one “right” paradigm fixes everything. Some ideas worked brilliantly, some were misunderstood, and some didn’t spread as widely as they could have.

The goal is practical: by the end, you should be able to look at modern apps and codebases with a clearer sense of why they feel the way they do—and what you can borrow for your next project.

The Problem He Was Trying to Solve

Alan Kay walked into a computing culture that was powerful, expensive, and mostly indifferent to ordinary people. Computers were treated like shared infrastructure: you booked time, submitted work, and waited for results. That model shaped everything—what programs looked like, who got to use them, and what “success” meant.

Batch computing: interaction was the exception

For many users, computing meant handing a job to the machine (often via cards or queued terminals) and getting output later. If something went wrong, you didn’t “poke around” and learn—you resubmitted and waited again. Exploration was slow, and the computer felt more like a remote service than a tool you could think with.

Personal computing as a different goal

Kay’s target wasn’t simply “smaller computers.” It was a different relationship: a computer as a personal medium for learning, writing, simulating, drawing, and building ideas—especially for children and non-specialists. That required immediacy. You needed to see what your actions did, revise quickly, and stay in a creative flow.

Why places like Xerox PARC mattered

To pursue that kind of change, you needed room to experiment with hardware, software, and interaction design together. Research labs such as Xerox PARC funded long bets: new displays, new input devices, new programming models, and new ways to package them into a coherent experience. The goal wasn’t to ship a feature—it was to invent a new kind of computer use.

Making user experience a first-class problem

If the computer was going to be a learning and creation machine, usability couldn’t be an afterthought. The interface had to support discovery, feedback, and understandable actions. That focus pushed Kay toward systems where the “feel” of interaction—what happens when you click, edit, or explore—was tightly connected to how the software itself was structured.

The Dynabook Vision: A Computer for Learning and Creating

Alan Kay didn’t start with “How do we make office work faster?” He started with a different question: what if a child could carry a personal computer like a book, and use it to explore ideas, make things, and learn by doing? That thought became the Dynabook—less a product spec and more a north star for personal computing.

Portable, personal, and learnable

The Dynabook was imagined as lightweight, battery-powered, and always available. But the most important word wasn’t “portable.” It was “personal.” This computer would belong to its user in the same way a notebook or instrument does—something you shape over time, not something you merely operate.

Just as important: it had to be learnable. Kay’s goal wasn’t to hide computing behind a wall of menus; it was to let people gradually become authors, not only consumers.

Education and creativity, not just productivity

The Dynabook’s “killer apps” were reading, writing, drawing, composing music, simulating science experiments, and building interactive stories. It treated programming as a literacy—another way to express ideas—rather than a specialized trade reserved for professionals.

That focus changes what “good software” means. A learning tool must invite tinkering, give quick feedback, and make it safe to try again.

How the vision shaped interfaces and languages

This is where Smalltalk and early graphical user interfaces fit in. If you want people to create, you need direct manipulation, immediate results, and an environment where experimenting feels natural. Smalltalk’s live, interactive system and the GUI’s visual metaphors supported the same goal: shorten the distance between an idea and a working artifact.

Bigger than any single device

The Dynabook wasn’t “predicting the tablet.” It was proposing a new relationship with computing: a medium for thought and creation. Many devices can approximate that, but the vision is about empowering users—especially learners—not about a particular screen size or hardware design.

Smalltalk as a Whole Environment, Not Just a Language

When people hear “Smalltalk,” they often picture a programming language. Kay’s team treated it as something bigger: a complete working system where the language, the tools, and the user experience were designed as one.

In plain terms, Smalltalk is a system where everything is an object. The windows on screen, the text you type, the buttons you click, the numbers you calculate—each is an object you can ask to do things.

A “live” system you can explore

Smalltalk was built for learning by doing. Instead of writing code, compiling, and hoping it works, you could inspect objects while the system was running, see their current state, change them, and immediately try a new idea.

That liveliness mattered because it turned programming into exploration. You weren’t just producing files; you were shaping a running world. It encouraged curiosity: “What is this thing?” “What does it contain?” “What happens if I tweak it?”

Language + tools + environment, tightly linked

Smalltalk’s development tools weren’t separate add-ons. Browsers, inspectors, debuggers, and editors were part of the same object-based universe. The tools understood the system from the inside, because they were built in the same medium.

That tight integration changed what “working on software” felt like: less like managing distant source code, more like interacting directly with the system you’re building.

A relatable analogy

Think of editing a document while it’s open and responsive—formatting changes instantly, you can search, rearrange, and undo without “rebuilding” the document first. Smalltalk aimed for that kind of immediacy, but for programs: you edit the running thing, see results right away, and keep moving.

Objects and Message Passing: The Core Mental Model

Kay’s most useful mental model isn’t “classes and inheritance.” It’s the idea that an object is a small, self-contained computer: it holds its own state (what it knows right now) and it decides how to respond when you ask it to do something.

Objects as “little computers”

Think of each object as having:

- Private memory (its state)

- A set of abilities (the actions it can perform)

- A front door (a way to receive requests)

This framing is practical because it shifts your focus from “Where is the data stored?” to “Who is responsible for handling this?”

Two views: data structures vs. actors

A common confusion is treating objects as fancy data records: a bundle of fields with a few helper functions attached. In that view, other parts of the program freely peek inside and manipulate the internals.

Kay’s view is closer to actors in a system. You don’t reach into an object and rearrange its drawers. You send it a request and let it manage its own state. That separation is the whole point.

Message passing, with an everyday example

Message passing is simply request/response.

Imagine a café: you don’t enter the kitchen and cook your own meal. You place an order (“make me a sandwich”), and you get a result (“here’s your sandwich” or “we’re out of bread”). The café decides how to fulfill the request.

Software objects work the same way: you send a message (“calculate total,” “save,” “render yourself”), and the object responds.

Why messages help systems evolve

When other parts of the system only depend on messages, you can change how an object works internally—swap algorithms, change storage, add caching—without forcing a rewrite everywhere else.

That’s how systems grow without breaking everything: stable agreements at the boundaries, freedom inside the components.

What “Object-Oriented” Really Means (and Common Confusions)

Plan the system clearly

Use Planning Mode to map the system conversation before you build anything.

People often treat “object-oriented programming” as a synonym for “using classes.” That’s understandable—most languages teach OOP through class diagrams and inheritance trees. But Kay’s original emphasis was different: think in terms of communicating pieces.

A few terms, plainly

A class is a blueprint: it describes what something knows and what it can do.

An instance (or object) is a concrete thing made from that blueprint—your specific “one of those.”

A method is an operation the object can perform when asked.

State is the object’s current data: what it remembers right now, which can change over time.

What Smalltalk pushed forward

Smalltalk helped popularize a uniform object model: everything is an object, and you interact with objects in a consistent way. It also leaned heavily on message passing—you don’t reach into another object’s internals; you send it a message and let it decide what to do.

That style pairs naturally with late binding (often via dynamic dispatch): the program can decide at runtime which method actually handles a message, based on the receiving object. The practical benefit is flexibility: you can swap behaviors without rewriting the caller.

Common confusions (and what to do instead)

- OOP is not “classes + inheritance.” Inheritance is one tool, and it’s often overused.

- OOP is not taxonomy. Naming and organizing types matters, but it’s not the goal.

A useful rule of thumb: design around interactions. Ask “What messages should exist?” and “Who should own this state?” If the objects collaborate cleanly, the class structure usually becomes simpler—and more change-friendly—almost as a side effect.

How GUIs Connect to the Object Model

A graphical user interface (GUI) changed what “using software” felt like. Instead of memorizing commands, you could point at things, move them, open them, and see results immediately. Windows, menus, icons, and buttons made computing feel closer to handling physical objects—direct manipulation rather than abstract instruction.

Direct manipulation is an object idea

That “thing-ness” maps naturally to an object model. In a well-designed GUI, nearly everything you can see and interact with can be treated as an object:

- A window is an object with state (size, position, title) and behavior (open, close, resize).

- A menu is an object that can display options and react to selections.

- An icon is an object that can be selected, dragged, and activated.

This isn’t just a programming convenience; it’s a conceptual bridge. The user thinks in terms of objects (“move this window,” “click that button”), and the software is built from objects that can actually do those actions.

Events become messages between objects

When you click, type, or drag, the system generates an event. In an object-oriented view, an event is essentially a message sent to an object:

- A click is a message to a button: “you were pressed.”

- Typing is a stream of messages to a text field: “insert this character.”

- Dragging is repeated messages: “pointer moved; update your position.”

Objects can then forward messages to other objects (“tell the document to save,” “tell the window to redraw”), creating a chain of understandable interactions.

Why it feels like a “place” to work

Because the UI is made of persistent objects with visible state, it feels like entering a workspace rather than running a one-off command. You can leave windows open, arrange tools, return to a document, and pick up where you left off. The GUI becomes a coherent environment—one where actions are conversations between objects you can see.

The “Live System” Idea: Feedback Loops and the Image

Own the codebase

Keep control by exporting source code whenever you want to maintain it your way.

One of Smalltalk’s most distinctive ideas wasn’t a syntax feature—it was the image. Instead of thinking of a program as “source code that gets compiled into an app,” Smalltalk treated the system as a running world of objects. When you saved, you could save the entire living environment: objects in memory, open tools, UI state, and the current state of your work.

Saving the whole running world

An image-based system is like pausing a movie and saving not just the script, but the exact frame, the set, and every actor’s position. When you resume, you’re back where you left off—with your tools still open, your objects still around, and your changes already in motion.

Why that enables fast feedback

This supported tight feedback loops. You could change behavior, try it immediately, observe what happened, and refine—without the mental reset of “rebuild, relaunch, reload data, navigate back to the screen.”

That same principle shows up in modern “vibe-coding” workflows too: when you can describe a change in plain language, see it applied immediately, and iterate, you learn the system faster and keep momentum. Platforms like Koder.ai lean into this by turning app-building into a conversational loop—plan, adjust, preview—while still producing real code you can export and maintain.

Modern parallels (without pretending they’re the same)

You can see echoes of the image idea in features people love today:

- Autosave and state restoration in apps

- Hot reload in some development tools

- Interactive notebooks where results appear as you work

These aren’t identical to Smalltalk images, but they share the goal: keep the distance between an idea and its result as short as possible.

The tradeoffs: power with sharp edges

Saving a whole running world raises hard questions. Reproducibility can suffer if “the truth” lives in a mutable state instead of a clean build process. Deployment is trickier: shipping an image can blur the line between app, data, and environment. Debugging can also become more complex when bugs depend on a particular sequence of interactions and accumulated state.

Smalltalk’s bet was that faster learning and iteration were worth those complications—and that bet still influences how many teams think about developer experience.

Thinking in Systems: Software as Interacting Parts

When Alan Kay talked about software, he often treated it less like a pile of code and more like a system: many parts interacting over time to produce behavior you care about.

A system isn’t defined by any single component. It’s defined by relationships—who talks to whom, what they’re allowed to ask for, and what happens as those conversations repeat.

Small parts, surprising outcomes

A few simple components can create complex behavior once you add repetition and feedback. A timer that ticks, a model that updates state, and a UI that redraws might each be straightforward. Put them together and you get things like animations, undo/redo, autosave, alerts, and “why did that just change?” moments.

That’s why systems thinking is practical: it pushes you to look for loops (“when A changes, B reacts, which triggers C…”) and time (“what happens after 10 minutes of use?”), not just single function calls.

Interfaces (messages) beat internal details

In a system, interfaces matter more than implementation. If one part can only interact with another via clear messages (“increment count”, “render”, “record event”), you can swap internals without rewriting everything else.

This is close to Kay’s emphasis on message passing: you don’t control other parts directly; you ask, they respond.

A simple example: button → model → log

Imagine three objects:

- Button: only knows how to announce a click.

- CounterModel: knows the current count and how to increase it.

- EventLog: records meaningful events.

Flow over time:

- Button sends

clicked. - Controller (or button) sends

incrementto CounterModel. - CounterModel updates state, then sends

changed(newValue). - UI listens to

changedand re-renders. - EventLog receives

record("increment", newValue).

No component needs to peek inside another. The behavior emerges from the conversation.

Designing for Humans: Learnability Over Cleverness

Alan Kay pushed a simple idea that still feels oddly radical: software should be easy to learn, not just powerful. “Clever” design often optimizes for the creator’s satisfaction—shortcuts, hidden tricks, dense abstractions—while leaving ordinary users stuck memorizing rituals.

Kay cared about simplicity because it scales: a concept that a beginner can grasp quickly is a concept teams can teach, share, and build on.

User empowerment: tools that help people think

A lot of software treats users like operators: press the right buttons, get the output. Kay’s goal was closer to a thinking tool—something that invites exploration, supports trial and error, and lets people build mental models.

This is why he valued interactive systems where you can see what’s happening and adjust as you go. When the system responds immediately and meaningfully, learning becomes part of using.

Education as a design driver (especially for children)

Kay often used learning—sometimes imagining children as users—as a forcing function for clarity. If a concept can be manipulated directly, inspected, and explained without hand-waving, it’s more likely to work for everyone.

That doesn’t mean “design only for kids.” It means using teachability as a quality test: can the system reveal its own logic?

Translating this into product decisions

Learnability is a product feature. You can design for it by:

- Reducing friction at the moment of first use: fewer steps, fewer surprises, clearer defaults.

- Making key concepts visible: show state, show relationships, show what will happen before it happens.

- Preferring discoverable actions over hidden ones: menus, affordances, and previews beat secret gestures.

The payoff isn’t just happier beginners. It’s faster onboarding, fewer support tickets, and a product people feel confident extending—exactly the kind of “user agency” Kay wanted software to amplify.

What Modern Software Borrowed (and What It Didn’t)

Try changes without fear

Experiment safely using snapshots and rollback while you explore different designs.

Kay’s work didn’t “invent everything we use now,” but it strongly influenced how many people think about building software—especially software meant for humans, not just machines.

What carried forward

A lot of modern practice echoes ideas that Smalltalk and the Xerox PARC culture made concrete and popular:

- Objects as active collaborators: Instead of treating a program as one big sequence of steps, you model it as parts that interact.

- Message-style communication: Even when we don’t literally “send messages” the Smalltalk way, we still design APIs and events as requests between parts of a system.

- GUI patterns: Windows, menus, controls, drag-and-drop, and direct manipulation all reflect a consistent belief: the interface should be learnable through exploration.

- Tools that shorten the feedback loop: Interactive debuggers, inspectors, live reload, REPLs, and strong IDE support are modern versions of the same goal—make change cheap, and learning continuous.

What changed (or didn’t survive)

Some parts of the original vision didn’t carry over cleanly:

- Scale and distribution: Smalltalk assumed a relatively coherent, local “world.” Modern systems are spread across devices, networks, and teams.

- Performance constraints: Today’s expectations (instant startup, battery efficiency, massive datasets) often push designs toward caching, batching, and careful resource control.

- The “whole environment” approach: Most developers don’t live inside a single shared image-based system; we juggle repositories, services, containers, and CI pipelines.

Modern echoes—used carefully

If you squint, many current patterns rhyme with message passing: component-based UIs (React/Vue), event-driven apps, and even microservices communicating over HTTP or queues. They’re not the same thing—but they show how Kay’s core idea (systems as interacting parts) continues to be reinterpreted under modern constraints.

If you want a practical bridge from history to practice, the last section (see /blog/practical-takeaways) turns these influences into design habits you can use immediately.

Practical Takeaways You Can Use in Your Next Project

Kay’s work can sound philosophical, but it translates into very practical habits. You don’t need to use Smalltalk—or even “do OOP”—to benefit. The goal is to build software that stays understandable as it grows.

A quick checklist: model the problem as collaborating roles

When you’re starting (or refactoring), try describing the system as a set of roles that work together:

- Name the roles in plain language (e.g., Cart, PricingRules, Inventory, Payment, Notification).

- For each role, write: “What does it know?” and “What can it do?”

- Keep each role small enough to explain in a few sentences.

- Make sure roles depend on behavior, not on each other’s internal data.

This keeps you focused on responsibilities, not on “classes because we need classes.”

Message-first thinking: define interactions before structures

Before you argue about database tables or class hierarchies, define the messages—what one part asks another part to do.

A useful exercise: write a short “conversation” for one user action:

- “Checkout asks PricingRules for a total.”

- “PricingRules asks Inventory whether items are available.”

- “Checkout asks Payment to authorize.”

- “Checkout tells Notification to send a receipt.”

Only after that should you decide how those roles are implemented (classes, modules, services). This is closer to Kay’s emphasis on message passing: behavior first, structure second.

Team advice: clear boundaries and short feedback loops

Kay cared about live systems where you can see the effects of changes quickly. In a modern team, that usually means:

- Clear boundaries: define what a component promises, and don’t let others reach into its internals.

- Short feedback loops: fast tests, preview environments, small pull requests, and frequent integration.

- Observable behavior: logs and metrics that tell you whether messages and workflows are succeeding.

If you can’t tell what changed—or whether it helped—you’re flying blind.

If you’re building with a chat-driven workflow (for example in Koder.ai), the same advice still applies: treat prompts and generated output as a way to iterate faster, but keep boundaries explicit, and use safeguards like snapshots/rollback and source-code export so the system stays understandable over time.

If you want to go deeper

If this section resonated, explore:

- Smalltalk (as an environment, not just syntax)

- Xerox PARC research and prototypes

- The Dynabook concept and “computing as a medium”

- Software systems thinking (how interacting parts create outcomes)

These topics are less about nostalgia and more about developing taste: building software that is learnable, adaptable, and coherent as a system.

FAQ

What problem was Alan Kay trying to solve with personal computing?

Alan Kay argued for a different relationship with computers: not queued batch jobs, but an interactive personal medium for learning and creating.

That mindset directly shaped expectations we now treat as normal—immediate feedback, manipulable interfaces, and software that can be explored and modified while you work.

What was the Dynabook, and why does it matter today?

The Dynabook was a vision of a portable, personal computer designed primarily for learning and creativity (reading, writing, drawing, simulation).

It’s less “he predicted tablets” and more “he defined what empowering computing should feel like”: users as authors, not just operators.

How is Smalltalk different from most modern programming languages?

In Smalltalk, the language, tools, and UI formed one coherent environment.

Practically, this means you can inspect running objects, change behavior, debug interactively, and keep working without constantly rebuilding and restarting—shortening the distance between an idea and a result.

What does “objects and message passing” mean in plain terms?

Kay’s core idea wasn’t “classes and inheritance.” It was objects as independent agents that communicate by sending messages.

Design-wise, that pushes you to define clear boundaries: callers rely on what messages an object accepts, not on its internal data layout.

What’s the most common misunderstanding about object-oriented programming?

A common trap is treating OOP as a type taxonomy: lots of classes, deep inheritance, and shared mutable data.

A better rule of thumb from Kay’s framing:

- Decide what roles exist.

- Define the messages between roles.

- Let internal structure be a consequence, not the starting point.

How do graphical user interfaces connect to the object model?

GUIs make software feel like you’re manipulating things (windows, buttons, icons). That maps naturally to an object model where each UI element has state and behavior.

User actions (clicks, drags, keystrokes) become events that are effectively messages sent to objects, which can then forward requests through the system.

What is a “live system” and what is the Smalltalk image?

A Smalltalk image saves the whole running world: objects in memory, open tools, UI state, and your current work.

Benefits:

- Very fast feedback loops

- Easy experimentation

Tradeoffs:

- Harder reproducibility

- More state-related “it depends how you got here” bugs

What does “systems thinking” change about how you design software?

Systems thinking focuses on behavior over time: feedback loops, cascading reactions, and who talks to whom.

In practice, it leads to designs with clearer interfaces (messages) and fewer hidden dependencies, because you treat the app as interacting parts—not just isolated functions.

How can I apply Kay’s ideas in my next project without using Smalltalk?

Use message-first design for one workflow:

- Write a short “conversation” describing one user action.

- Name the roles (e.g., Checkout, PricingRules, Inventory, Payment).

- Define the messages (e.g.,

getTotal,isAvailable,authorize).

Only then choose implementations (classes, modules, services). The post’s checklist in /blog/practical-takeaways is a good starting point.

What are the best modern parallels to Smalltalk and PARC ideas?

Modern tools often rhyme with Kay’s goals even if they implement them differently:

- Hot reload, REPLs, interactive debuggers → shorter feedback loops

- Component UIs and event-driven architectures → message-like interactions

- Autosave and state restoration → echoes of “keep your place”

They’re not the same as Smalltalk images, but they pursue the same practical outcome: make change and learning cheap.