Aug 10, 2025·8 min

Amazon’s Flywheel: Logistics, Prime, and AWS Reinforcement

Learn how Amazon’s logistics network, Prime membership, and AWS strengthened each other—improving speed, lowering costs, and funding expansion.

Learn how Amazon’s logistics network, Prime membership, and AWS strengthened each other—improving speed, lowering costs, and funding expansion.

People often talk about the “Amazon flywheel” as if it’s a single trick: lower prices → more customers → repeat. That story is useful—but incomplete. The bigger insight is how a few major systems amplified each other so the whole became more powerful than any part on its own.

A flywheel is a self-reinforcing loop: you push in one place, it creates momentum, and that momentum makes the next push easier. In business terms, one advantage (like faster delivery) increases demand, which funds improvements, which increases demand again.

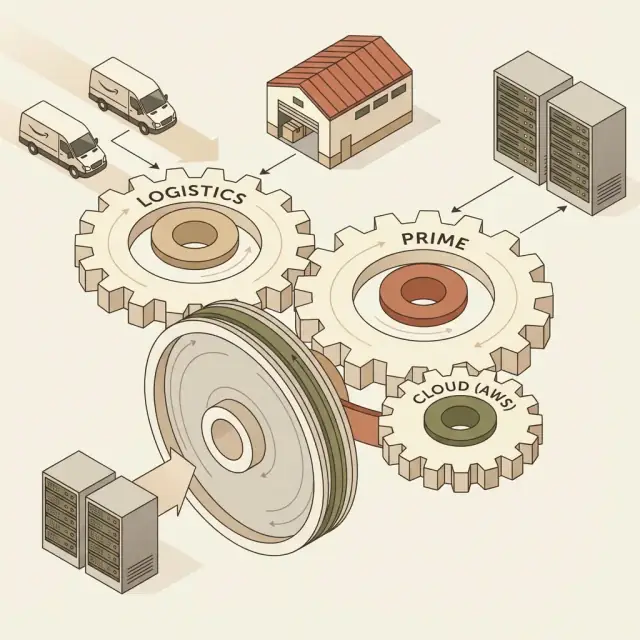

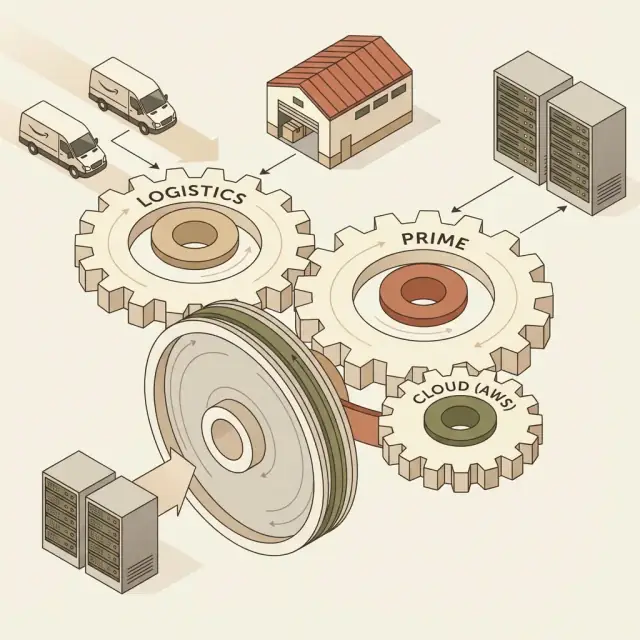

Amazon’s flywheel is most interesting when you look at how the pushes connect—especially across three pillars:

It explains why Amazon was willing to spend heavily for years: logistics density improves with volume; Prime increases frequency; frequency justifies more facilities; and AWS profits and cash flow created more room to reinvest.

A flywheel diagram can hide hard realities: timing matters, capital is constrained, execution is messy, and some advantages are not self-reinforcing (they can stall or reverse). It also doesn’t automatically prove causation—some gains came from one-off bets, not loops.

We’ll map the inputs and feedback loops, then zoom into logistics, Prime, and AWS—before pulling it together into what was hard to copy, where it can slow down, and practical ways to apply flywheel thinking yourself.

A flywheel is easiest to understand when you separate inputs (what you invest) from outputs (what you get back), and then spot how the outputs make the next round of inputs cheaper or more effective.

At a high level, Amazon’s retail flywheel can be mapped like this:

Then reinvestment feeds back into selection and experience, and the wheel turns again.

“Unit economics” means the cost and profit per basic unit of business.

A simple logistics example: if running a delivery route (driver, van, fuel) costs $400 per day and it delivers 100 packages, that’s $4 per package. If the same route—because of higher demand and better density—delivers 160 packages, the cost becomes $2.50 per package. Nothing magical happened; volume and routing efficiency changed the math.

You can tell a similar story per order: if packing + shipping averages $6 per order at low volume, getting it to $4 at higher volume creates room to lower prices, speed up delivery, or fund Prime benefits.

A one-time advantage is something you can “win” once (a great holiday season, a viral product). A feedback loop is different: the result improves the system that produces the result. More orders improve density and forecasting, which lowers cost and improves delivery, which attracts more orders.

Flywheels aren’t instant. The compounding benefit shows up after many turns—when small improvements in cost per package, delivery speed, and selection stack on each other over years.

Amazon’s retail engine isn’t powered only by “fast shipping.” It’s powered by a logistics system that turns speed into a cost advantage—and then uses that cost advantage to fund even more speed.

Fulfillment centers (and the delivery capacity that surrounds them) shorten the path from “order placed” to “out for delivery.” More buildings, more automation, more sortation sites, and more last-mile options mean fewer handoffs and fewer miles traveled per package.

When the network has slack—enough trailers, drivers, linehaul routes, and local delivery routes—Amazon can ship sooner and recover from spikes. That reduces delivery times, but it also reduces expensive fixes like rerouting, air shipments, and customer service escalations.

Density means lots of orders going to the same geographic area. When a delivery van can drop 140 packages on a tight route instead of 60 spread across a wide area, the cost per package falls.

The same logic applies inside warehouses and between facilities: higher volume enables better utilization of labor, robotics, and transportation. Even small improvements—one less mile per stop, fewer empty cages, fuller trucks—compound at Amazon scale.

A key lever is positioning inventory near customers. If popular items are stocked in the right regional nodes, the system can offer faster delivery without paying premium transport. It’s often cheaper to move inventory in bulk in advance than to rush individual orders after the fact.

Fewer delays build trust. When delivery is consistently predictable, customers order more frequently and with less “backup” shopping elsewhere—boosting volume, which feeds density and further lowers per-package costs.

Marketplace sellers add selection, but their volume also fills the network. When more third-party orders flow through fulfillment services, Amazon gets additional shipment density and steadier demand—helping justify more facilities and routes, which improves speed for everyone.

Prime is often described as “free shipping,” but its real job is behavioral: it’s a commitment device. Once someone pays an annual (or monthly) fee, they feel a subtle pressure to “get their money’s worth.” That usually shows up as more frequent orders, more categories tried, and fewer comparison-shopping detours.

Fast, reliable shipping changes the math of a purchase. When delivery is quick and predictable, customers are less likely to delay (“I’ll wait until I need a few things”) or abandon their cart because shipping feels uncertain or expensive.

A simple chain reaction kicks in:

That volume isn’t just revenue—it’s signal. It tells Amazon which items people want quickly, and where.

Retail is famously spiky: holidays, promotions, and random swings make forecasting hard. Prime smooths those peaks and valleys because members keep coming back even when prices aren’t the absolute lowest. The subscription creates a relationship, not just a transaction.

This retention effect matters because it makes demand more predictable. Predictable demand supports better logistics planning: how many drivers to schedule, where to position inventory, which delivery routes will stay busy, and when new capacity will be utilized rather than sitting idle.

Streaming video, music, exclusive deals, and other perks help Prime feel sticky. They reduce cancellation risk and keep the membership top of mind. But they’re best understood as reinforcement—adding reasons to stay—while the core driver is still shipping speed and reliability.

Prime turns shipping from an occasional fee into an everyday expectation. That expectation pulls demand forward, and that steady demand makes it easier to keep improving fulfillment and delivery performance.

Prime didn’t just “offer free shipping.” It changed customer behavior in a way that made Amazon’s logistics investments pay off faster.

When customers pay for Prime, they’re more likely to default to Amazon for everyday purchases—because each additional order feels frictionless. That consistency matters operationally: higher, steadier order volume justifies adding fulfillment centers closer to demand, opening more delivery stations, running more routes, and investing in automation (sortation, packing, forecasting) that only makes sense at scale.

Once those assets are in place, unit economics improve. A denser network means shorter last-mile distances, better truck utilization, and more packages per stop—reducing cost per package and freeing up budget for even faster delivery promises.

Better service (faster, more reliable delivery options) increases demand.

More demand improves economics (higher density and utilization).

Better economics funds more service improvements (more sites, automation, delivery capabilities).

Then the loop repeats.

Speed isn’t only about convenience—it changes the basket. When delivery shifts from “in a few days” to “today or tomorrow,” customers become comfortable ordering items that used to require a local store run: toiletries, snacks, last-minute gifts, and household essentials. That broadens order frequency and item mix, which further increases volume and network density.

Holiday spikes and promotional events create sudden surges in demand. A larger network—with more nodes, flexible labor pools, and diversified routes—can absorb those spikes more effectively. Even when costs rise during peaks, the underlying scale helps prevent service levels from collapsing, protecting Prime’s core promise and keeping customers in the habit.

AWS is easiest to understand as “renting computing over the internet.” Instead of buying servers, running data centers, and guessing how much capacity they’ll need, companies can rent processing power, databases, and storage on demand—paying for what they use.

That simple idea created something strategically unusual for Amazon: a large business with steadier, contract-like revenue dynamics than retail. Retail can be seasonal, promotion-heavy, and sensitive to shipping and inventory surprises. Cloud infrastructure, by contrast, tends to be embedded into a customer’s operations. Once a company builds on it, it’s sticky.

Because AWS generates cash with less dependence on holiday peaks and product margins, it can increase Amazon’s capacity to make long-horizon investments. The mechanism isn’t “AWS pays for everything,” but that a more predictable profit engine can:

Amazon’s retail business is a demanding internal customer: huge traffic spikes, massive catalogs, constant personalization, and the expectation that the site simply cannot go down. Meeting those needs forces excellence in reliability, monitoring, security, and data handling. Those capabilities translate directly into better cloud products.

At the same time, AWS tools can improve retail operations—forecasting, routing, fraud detection, and experimentation—because the company is building and using the same building blocks.

AWS is run as its own business, with its own customers and priorities. Still, strategic benefits can flow across the company: shared technical standards, talent, and an overall ability to keep funding big, timed bets that keep the broader flywheel moving.

Amazon’s flywheel isn’t only about trucks, warehouses, and subscriptions. A big part of the compounding effect came from shared technology and shared learning across the company—especially between retail operations and AWS.

Every purchase, search, return, and delivery attempt produces signals. At scale, those signals help answer practical questions: Which items spike seasonally? Which ZIP codes have high return rates? Where do delivery promises routinely slip?

Better forecasting reduces stockouts (lost sales) and overstock (cash tied up). It also changes where inventory should sit. If demand is predictable, you can place items closer to customers, cut shipping distance, and improve delivery speed without proportionally increasing cost.

Many foundational building blocks are useful whether you’re running an online store or a cloud platform:

These same capabilities can power tools that optimize warehouse slotting, picking routes, labor planning, and linehaul/last-mile transportation—classic operations research problems, just fed by better data.

Running a global cloud service trains teams to treat uptime, monitoring, and incident response as non-negotiable. That reliability expectation can spill into retail systems—forecasting pipelines, inventory feeds, and fulfillment software—where minutes of downtime can cascade into missed promises.

The key point: this doesn’t require forced synergy. Shared tools are valuable even when teams build for their own goals; the compounding comes from reusable patterns, internal platforms, and accumulated operational discipline.

Amazon’s flywheel wasn’t powered by small optimizations alone. It required large, timed capital decisions—especially in logistics—where the payoff depends on volume.

Building fulfillment centers, sortation hubs, delivery stations, and last-mile capacity is expensive and hard to undo. Much of the cost is fixed: leases, automation equipment, vehicles, and staffing infrastructure. If demand doesn’t arrive as expected, you’re left with underused capacity and a higher cost per package.

That’s the core risk of retail logistics: you have to invest ahead of demand to improve speed and reliability, but those improvements only become economical when utilization stays high.

Prime helped create demand certainty. A subscription shifts customer behavior from occasional purchases to a habit—more frequent orders, higher share of wallet, and lower churn. That steadier volume makes logistics investments less speculative because capacity is more likely to be used.

AWS strengthened funding capacity. Even if retail margins were thin (or negative) in a given period, a profitable cloud business could support long-term reinvestment. This doesn’t eliminate risk, but it allows management to keep investing through cycles when a pure retailer might be forced to pause.

The more Amazon owned (instead of outsourcing), the more control it gained over speed and customer experience—but the higher the fixed-cost base. That raises the stakes: utilization must remain high, forecasting must be good, and expansion must be staged.

To keep the flywheel turning, reinvestment typically needs to follow the tightest bottleneck:

The lesson is sequence: big bets work when they’re timed to unlock the next constraint—not when they’re simply “more capacity.”

Amazon’s marketplace added a second growth engine to retail: third-party sellers. Instead of Amazon buying every item upfront, millions of merchants could list products themselves—expanding selection far faster than any single retailer could. More selection meant more chances a shopper would find exactly what they wanted, which increased conversion and repeat visits.

Third-party sellers fill the long tail: niche sizes, colors, replacement parts, imported goods, and small brands. That breadth reduces the need for customers to shop around elsewhere. It also improves price competition, which matters because customers don’t separate “Amazon the store” from “Amazon the marketplace”—they experience one unified catalog.

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) changed the seller value proposition. A merchant could send inventory into Amazon’s fulfillment network and instantly offer faster shipping, Prime eligibility, and professional packing. That speed and reliability often lifted sales enough to justify the fees.

For Amazon, FBA also standardized operations: predictable packaging, fewer shipping errors, and simpler customer service workflows.

Marketplace growth only works if customers keep trusting the purchase. Key levers are delivery speed, accurate tracking, easy returns, and consistent issue resolution. If an item arrives late or returns are painful, customers blame Amazon—even when the seller caused the problem—so enforcing service standards becomes essential.

As marketplace orders rise, Amazon ships more packages through the same regions and routes. That density improves truck utilization, increases warehouse throughput, and spreads fixed costs across more units—reducing cost per package. Lower fulfillment costs enable better delivery promises, which makes the marketplace even more attractive to both customers and sellers.

Many competitors can copy individual tactics—free shipping thresholds, a paid membership, faster delivery promises, even a decent fulfillment operation. The hard part is copying the closed loop where each piece makes the others cheaper, better, and more defensible over time.

A subscription can buy loyalty, but only if the benefit is consistently delivered. Fast shipping can attract customers, but only if it becomes more efficient as volume rises. A marketplace can add selection, but only if sellers trust the platform’s traffic and fulfillment services enough to invest.

Amazon’s advantage was that these weren’t separate initiatives. Higher order volume justified more fulfillment nodes. More nodes increased speed and lowered per-package costs through density. Better shipping reliability made Prime more valuable, lifting retention and purchase frequency. That created even more volume.

Competitors often hit three limits:

This flywheel isn’t invincible. Rising transportation and labor costs can squeeze economics. Regulatory pressure can affect marketplace rules, data use, and pricing. Customer sentiment can shift if delivery quality drops or Prime feels less valuable.

To compare flywheels across companies, ask:

If a competitor can’t answer all four with credible scale, they may copy the features—but not the flywheel.

The flywheel idea is useful, but it’s not a perpetual-motion machine. When one input stops improving—or gets more expensive—feedback loops can weaken quickly. For Amazon, the biggest risks cluster around operations, customer expectations, and cloud economics.

Fast delivery is compelling, but it’s also a cost trap if volume, density, or network utilization slips. Rising last-mile costs (fuel, vehicles, insurance), labor constraints (hiring, wages, union pressure), and capacity mismatches can all increase cost per package.

Utilization swings matter more than most people realize. If Amazon builds for peak demand and then demand normalizes, fixed costs don’t disappear—empty trucks and underused facilities directly dilute unit economics. That can force uncomfortable trade-offs: slower delivery promises, higher fees, or reduced investment.

Prime works best when it becomes a habit, but habits can break if customers feel they’re paying more for the same (or worse) experience. Membership fatigue shows up when subscription renewals start depending on price sensitivity rather than perceived value.

There’s also a quality ratchet: once customers expect one-day shipping and easy returns, any dip—late deliveries, stricter return policies, inconsistent product quality—feels like a loss, not a neutral change.

At a high level, AWS is exposed to competition, pricing pressure, and enterprise buying cycles. When companies optimize costs or delay new projects, cloud growth can slow, reducing the profit cushion that funds long-term reinvestment.

Ultimately, flywheels slow when a pillar weakens: logistics costs rise, Prime retention softens, or AWS margin compresses. The system can still work—but it needs re-tuning, not just momentum.

Amazon’s flywheel is famous because it’s big—but the useful part is the structure: a clear promise, behaviors that repeat, and economics that improve with every turn. You can apply the same logic at a much smaller scale.

Use this as a working template (and keep iterating it on paper until it feels obvious):

You don’t need warehouses or a cloud platform to run flywheel thinking. You need a repeatable system.

For a local retailer, a Prime-like move could be a membership for free pickup, priority restocks, and easy returns. For a service business, it could be a monthly plan with guaranteed response times. For an e-commerce brand, it might be consolidated shipping days, negotiated carrier rates, and packaging that reduces damage and returns.

Start with “boring” reinvestments that pay back quickly: reduce rework, cut customer support tickets with clearer instructions, standardize packaging, batch deliveries by neighborhood, or shift demand into predictable windows.

If your flywheel is software-led, the same logic applies: reduce the cost of delivering value (time-to-first-value, support load, deployment friction), then reinvest into the promise. Tools like Koder.ai can help teams prototype and ship those improvements faster by turning product requirements into working web, backend, or mobile apps through a chat-driven workflow—useful when you want quick iterations, snapshots/rollback, and deployable builds without a heavy pipeline.

Track a few measures that connect promise → behavior → economics:

A healthy flywheel strengthens three reinforcements: demand (more customers returning), cost (lower unit costs as volume and process improve), and reinvestment (using gains to make the offer even better)." }

A flywheel is a self-reinforcing loop where one improvement makes the next improvement easier. In this article’s framing, the loop looks like:

The key is that outputs (like higher volume) improve the system that produces the next outputs (like lower cost per package).

It explains why reinvestment can make sense for a long time: higher volume improves logistics density and utilization, which lowers cost per package and enables better delivery promises. Those better promises increase repeat purchases—especially with Prime—creating more volume.

It’s most helpful for understanding compounding systems (logistics + Prime + marketplace + data), not isolated tactics like “free shipping.”

A flywheel diagram can hide constraints and messiness. It doesn’t automatically account for:

It’s a useful mental model, but not proof of causation or inevitability.

Unit economics means the profit and cost per basic unit (like per package or per order). In logistics, small changes in density can dramatically change unit cost.

Example from the post: if a route costs $400/day, delivering 100 packages is $4/package; delivering 160 packages is $2.50/package. That drop can be converted into lower prices, faster delivery, or better Prime benefits.

Speed requires capacity and smart placement.

Often, “closer” beats “faster”: pre-positioning inventory in bulk can be cheaper than rushing individual orders after checkout.

Prime converts shipping from a per-order decision into an ongoing commitment. Once customers pay the membership fee, they tend to:

That increased frequency creates steadier volume, which makes logistics investments pay off faster and strengthens the loop.

Prime increases order frequency and stabilizes demand, which improves planning and utilization. That makes it easier to justify adding facilities, routes, and automation.

Then logistics improvements (speed and reliability) make Prime feel more valuable, which supports renewals and habit formation. The two reinforce each other through predictable volume → better economics → better service.

AWS provides a profit and cash-flow engine with different dynamics than retail (often steadier and stickier once customers build on it). That can:

It’s not “AWS pays for everything,” but it can increase Amazon’s capacity to fund long-horizon bets.

Marketplace expands selection via third-party sellers, which increases conversion and repeat visits. When sellers use fulfillment services (like FBA), their volume also flows through Amazon’s network, adding shipment density.

Benefits described in the post include:

That added density can lower cost per package and improve delivery promises across the system.

Start with one promise, one bottleneck, and one measurable loop.

Practical approach:

Track a small set of metrics that connect promise → behavior → economics: retention, speed, unit cost, and repeat rate.