Mar 06, 2025·8 min

Amazon’s Flywheel Explained: Platform, Logistics, and AWS

A clear guide to Jeff Bezos’ Amazon flywheel: how customer focus, marketplace network effects, fulfillment scale, and AWS economics reinforce each other.

What Amazon’s Flywheel Means (Without the Jargon)

A “flywheel” is a simple idea: one good thing makes the next good thing easier, and the cycle builds momentum over time. Think of pushing a heavy wheel—at first it barely moves, but each push adds speed. Eventually, the wheel helps carry itself.

Jeff Bezos liked this model because it focuses on repeatable, connected moves instead of one-off “big bets.” A big bet can work, but it can also fail and leave you back where you started. A flywheel is different: even small improvements (faster delivery, better prices, more selection) stack together. If one push is a little weaker one year, the rest of the wheel can still keep turning.

What you’ll get from this article

We’ll break down Amazon’s flywheel without business-school vocabulary, focusing on three engines that reinforce each other:

- Platform thinking: how a marketplace can turn traffic into more selection—and more selection back into traffic.

- Logistics as a product: how fulfillment speed and reliability become part of what customers “buy,” not just a cost.

- Cloud economics (AWS): how turning internal infrastructure into a service creates cash flow and efficiency that can be reinvested.

A quick map of the loops we’ll discuss

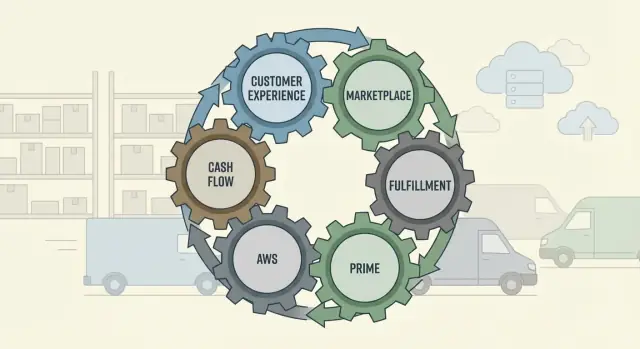

Amazon’s flywheel is really several connected loops:

- Customer experience loop: better prices + selection + convenience → more customers → more volume.

- Marketplace loop: more customers → more sellers → more selection → better shopping experience.

- Fulfillment loop: more volume → denser logistics network → faster/cheaper shipping → more customers.

- Prime frequency loop: membership benefits → more orders per customer → more predictable demand.

- AWS reinvestment loop: efficient infrastructure → profitable cloud business → more money to improve everything else.

By the end, you should be able to spot flywheels in other companies—and design a smaller version for your own product.

The Customer Experience Loop at the Center

Amazon’s flywheel starts with a simple idea: make the customer experience better, and everything else gets easier to grow.

At the center are a few basics customers actually feel:

- Selection: more of what you want, in more sizes, brands, and price points.

- Price: not always the cheapest on every item, but consistently competitive.

- Convenience: fast delivery, simple checkout, and low-friction returns.

- Trust: accurate product pages, reliable delivery promises, and predictable customer service.

How a better experience turns into more traffic (and more repeats)

When selection improves and delivery is faster, more people choose Amazon as their “default” store. That increases traffic. More traffic leads to more purchases, more reviews, and more data about what people want—which helps improve product pages, recommendations, and inventory decisions.

Just as important, a great experience increases repeat purchases. The flywheel isn’t only about attracting new shoppers; it’s about becoming the habit people return to when they need something quickly and with low risk.

Customer focus as a guide for trade-offs

“Customer obsession” sounds like a slogan, but it’s really a decision filter.

- Speed vs. cost: spending on faster shipping can be justified if it boosts conversion and repeat frequency.

- Breadth vs. depth: carrying more categories (breadth) may matter more than having every niche option in one category (depth), depending on what reduces customer effort.

Simple, concrete examples

A one-day delivery promise that’s consistently met builds trust and reduces purchase hesitation. Easy returns lower the perceived risk of ordering clothing or electronics. Reliable product pages—clear photos, accurate specs, real reviews—cut down on “surprises,” which reduces returns and increases satisfaction.

This is the loop: improve experience → earn more demand → learn faster → reinvest to improve experience again.

Marketplace Platform Thinking: Turning Traffic into Selection

Amazon’s marketplace move was a straightforward platform bet: instead of stocking every product itself, invite third-party sellers to list alongside Amazon’s own inventory. That turns customer traffic into a magnet for selection—because sellers show up where demand already exists.

Selection without owning the inventory

Third-party sellers expand what customers can buy without Amazon purchasing, storing, and risking unsold inventory for every niche item. A small brand can list a single specialty SKU; a large merchant can add thousands of variations. The result is “endless aisle” breadth that would be expensive (and slow) for a traditional retailer to build alone.

Why more sellers can improve price and availability

When multiple sellers offer the same or similar products, customers get:

- More price competition (which often pushes prices down)

- Better availability (if one seller runs out, another may still have stock)

- Faster delivery options (different sellers may hold inventory in different places)

For Amazon, this can raise conversion: shoppers find what they want more often, so they return more often.

The hard part: trust at marketplace scale

Marketplaces aren’t “set it and forget it.” More sellers can also mean more inconsistency: misleading listings, counterfeit goods, review manipulation, and uneven shipping performance. If customer trust drops, the entire selection advantage backfires.

Amazon’s answer is a set of mechanisms that make participation conditional:

- Ratings and reviews that surface reliable sellers and products

- Clear policies on authenticity, returns, and prohibited items

- Enforcement (warnings, suspensions, and removals) to deter bad actors

- Seller tools for listings, pricing, ads, and support—so good sellers can scale

The marketplace flywheel works when selection grows and trust stays high. Amazon’s platform thinking is about engineering both at the same time.

Network Effects and Trust: Why Scale Can Compound

Amazon’s marketplace has a simple compounding loop: more buyers attract more sellers, and more sellers attract more buyers.

Buyers show up because they expect convenience and low prices. Sellers show up because that traffic can turn into sales. As sellers compete, selection improves (more brands, more niches, more price points). That wider selection gives buyers another reason to start their search on Amazon—feeding the same loop again.

The “Trust Layer”: Reviews, rankings, and visibility

Scale alone isn’t enough. What makes the loop compound is trust—the belief that you’ll find what you want and that it will match expectations.

Amazon’s review system, star ratings, and search ranking reinforce demand in two ways:

- Social proof reduces risk. A product with thousands of credible reviews feels safer than an unknown alternative.

- Ranking concentrates attention. Higher-converting listings rise, get more exposure, and often generate even more sales and reviews.

This can create a winner-takes-most dynamic where a few top listings capture a large share of clicks.

When network effects weaken

Network effects are fragile when trust erodes. If customers run into counterfeit products, misleading listings, or low-quality knockoffs, they may stop browsing—or stop starting their search on Amazon at all.

Discovery can also break the loop. If search results feel noisy, repetitive, or optimized for hacks rather than relevance, buyers lose confidence, and sellers with genuine quality may invest less.

How rules improve quality over time

Platforms compound best when they set rules that make participation better for everyone. Amazon has steadily tightened standards—policing restricted products, pushing performance metrics, and rewarding reliable fulfillment and service.

These rules can feel strict to sellers, but they’re a key reason scale can increase overall quality instead of diluting it.

Logistics as a Product: Fulfillment Scale and Speed

Amazon treats logistics less like a back-office cost center and more like a customer-facing product. The “product” is simple: the right item arrives quickly, predictably, and with painless returns. When that works, customers buy more often—and sellers list more items because delivery no longer depends on each merchant’s capabilities.

What a fulfillment network actually does

A modern fulfillment network is a coordinated set of capabilities that turns inventory into delivered orders:

- Storage: placing items in warehouses (often multiple locations) to be close to demand.

- Picking and packing: locating the item fast, packaging it correctly, and batching work efficiently.

- Shipping and delivery: moving parcels through carriers or last‑mile routes.

- Returns: making it easy for customers to send items back and for inventory to be reprocessed.

Each step is a chance to reduce time, errors, and friction—things customers notice immediately.

Why “density” lowers the cost per delivery

A key idea is density: more orders in the same geographic area and time window. Higher density means delivery routes can drop more packages per mile, warehouses can justify being closer to customers, and labor and equipment get used more consistently. Even small improvements here can lower the per-unit cost of delivery, which can then be reinvested into lower prices, faster shipping options, or better service.

Speed isn’t just nice—it changes buying behavior

Faster, more reliable delivery boosts conversion because it reduces hesitation at checkout. If a shopper believes the item will arrive when they need it, they’re less likely to abandon the cart or delay the purchase. Speed also reduces customer support issues (“Where is my order?”), which improves the overall experience.

The trade-offs Amazon accepts

This system requires heavy investment and careful planning:

- Capital spending and fixed costs for warehouses, automation, and transportation capacity.

- Peak season variability, where demand spikes can strain the network or leave capacity underused later.

The bet is that scale and learning effects make the network better over time—and that better logistics feeds the flywheel.

FBA: Connecting Sellers to the Fulfillment Engine

Fuel your build budget

Create content or refer teammates and earn credits to keep building and shipping iterations.

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is Amazon’s “let us handle the heavy lifting” option for third‑party sellers. Instead of shipping every order themselves, sellers send inventory in bulk to Amazon warehouses. Amazon then stores it, picks and packs each order, ships it, and often handles returns and customer service.

Why it matters in a marketplace

A marketplace grows when customers can reliably find what they want and receive it quickly. FBA turns thousands (or millions) of independent sellers into a more consistent shopping experience—because the last mile is run through the same fulfillment system.

That consistency is valuable: delivery speed, packaging quality, tracking, and returns policies become standardized. For shoppers, it reduces “Will this seller mess up my order?” anxiety. For Amazon, it means more orders can meet the expectations that keep customers coming back.

How FBA expands Prime-eligible selection

When a seller uses FBA, many of their listings become eligible for fast shipping—often Prime. That matters because customers tend to filter for fast delivery and trust Prime badges. More Prime‑eligible items means more choice without sacrificing convenience, which can increase conversion and order frequency. In flywheel terms: more sellers → broader selection → better customer experience → more demand → more sellers.

Tensions and risks to watch

FBA isn’t “free value.” Fees can rise, and storage charges can punish slow-moving inventory. Amazon can also impose inventory limits, forcing sellers to manage forecasts carefully.

There’s also dependency risk: when fulfillment, customer contact, and performance metrics run through Amazon, sellers may feel locked in. FBA can accelerate a business—but it can also concentrate power in the platform that controls the fulfillment engine.

Prime’s Role: Membership Economics That Boost Frequency

Prime isn’t just a discount bundle. It’s a behavior change mechanism: once shipping feels “already paid for,” people stop doing the mental math on every order. That reduction in friction matters more than it sounds—when the cost (and hassle) of checkout decisions drops, small, frequent purchases become normal.

Prime as a habit-builder

Without Prime, many shoppers batch orders to “make shipping worth it.” With Prime, the default shifts toward buying when the need appears: a phone cable today, detergent tomorrow, a last-minute gift on Friday. That higher purchase frequency feeds the flywheel by increasing demand and giving Amazon more opportunities to learn what customers want.

Membership economics that fund speed

The annual fee creates a predictable pool of revenue that’s less tied to any single product margin. That money can be reinvested into faster shipping, more delivery stations, better routing software, and additional inventory placement—investments that are expensive up front but powerful once scaled.

The key is that better delivery performance makes Prime feel more valuable, which encourages renewals and attracts new members, which expands the revenue base for more delivery investment.

LTV and demand predictability

Prime tends to increase lifetime value (LTV) not only because members order more, but because they stick around. For planning, a large membership base also makes demand more predictable: when you know a segment of customers is likely to order frequently, it’s easier to justify capacity decisions and inventory positioning.

The hard limit: the promise must be kept

Prime’s value depends on consistent delivery performance. If “two-day” becomes “maybe next week,” the membership stops reducing friction and starts creating disappointment. Prime works best when the operations engine can reliably deliver on the promise at scale.

Unit Economics: How Volume Can Lower Costs

Ship the next improvement today

Create a simple web app in React from a short prompt, then iterate on what users want.

Amazon’s flywheel isn’t magic; it’s largely math. Unit economics asks a simple question: after you deliver one more order, do you get cheaper or more expensive to operate per package?

Fixed vs. variable costs in the real world

Some costs don’t change much with volume—at least in the short run. A warehouse lease, conveyor systems, robotics, sortation equipment, aircraft ownership/leases, and major routing software are largely fixed costs. You pay for the capacity whether you ship 10,000 packages or 100,000.

Other costs rise with each additional order: variable costs like packaging materials, payment processing, hourly labor for picking/packing, fuel per mile, and last‑mile delivery time.

How volume spreads fixed costs

When volume increases, fixed costs get divided across more units. If a fulfillment center costs $X per month to operate, more orders can push the fixed cost per order down—assuming you’re using the building and equipment efficiently.

Delivery routes show the same effect. A van leaving the depot has a baseline cost (driver time, vehicle depreciation, planned route distance). If you can place more stops on that route without adding much extra time, the average cost per stop drops.

Reinvesting the savings: price, speed, or both

Lower unit costs create room to improve the customer offer. Amazon can reinvest gains into:

- Lower prices (or fewer fees) to increase conversion

- Faster delivery by adding capacity closer to customers

- Better reliability through more inventory buffering and redundancy

Those improvements tend to increase order frequency, which increases volume again—feeding the flywheel.

Scale only helps if efficiency holds

Volume is not automatically good. If warehouses get congested, accuracy drops, returns spike, or delivery networks become overextended, unit costs can rise. The flywheel depends on operational discipline: forecasting demand, keeping utilization high without bottlenecks, and continuously improving processes so scale translates into real per‑order savings.

AWS: Turning Internal Infrastructure into a Business

Amazon didn’t set out to build a cloud company. It set out to run Amazon.com at huge scale—and discovered that the “boring” parts of the business (servers, storage, databases, networking, monitoring) were becoming a competitive advantage.

Origins: infrastructure built for Amazon’s own pain points

As Amazon’s retail and marketplace businesses grew, teams needed a faster way to launch new features without waiting on shared IT resources. That pressure pushed Amazon to standardize how it provisioned compute, stored data, and managed reliability. The big shift was treating infrastructure like a set of repeatable building blocks—usable by any internal team on demand.

Once those building blocks existed, Amazon had something valuable: a machine for turning capacity into products.

From “spare capacity” to a product catalog

When the company realized its internal platform could serve others, it began packaging the core components as services:

- Compute (rent processing power when you need it)

- Storage (durable, scalable data storage)

- Databases (managed systems that reduce operational overhead)

This wasn’t just reselling servers. The product was abstraction: customers didn’t have to buy hardware, predict demand months ahead, or maintain as much underlying plumbing.

Why pay-as-you-go pulled in startups and enterprises

Pay-as-you-go pricing changed the buying decision. Startups could experiment without large upfront costs, and enterprises could shift spending from capital purchases to operating expense—often with faster procurement and clearer cost allocation per team or project.

It also encouraged usage-based growth: as a customer’s product succeeded, AWS usage rose naturally, without renegotiating a giant contract every time capacity needs changed.

Cloud scale: lowering costs and funding new capability

As AWS gained more customers, it could buy hardware more efficiently, improve utilization, and spread fixed costs (data centers, networking, security) across a larger base. Those savings weren’t only profit—they funded more regions, more services, and better reliability.

That reinvestment loop strengthened Amazon’s broader flywheel: AWS generated cash, improved technical capabilities, and made it easier for Amazon teams (and external builders) to move faster with fewer constraints.

Cloud Economics and Reinvestment: Fuel for the Flywheel

AWS matters to the flywheel less as “tech magic” and more as a financial engine. Cloud services tend to produce higher margins than retail because they sell standardized capacity (compute, storage, networking) at scale, with heavy automation. When that engine throws off cash, Amazon has more room to make long-term bets that would be hard to justify if the whole company depended only on thin retail margins.

Reinvestment as a repeatable pattern

The flywheel-friendly move isn’t simply “make profit,” it’s “reinvest to improve the experience,” then let that improvement drive more volume.

Examples of reinvestment patterns that fit this logic:

- Lower prices or more frequent deals, even if it compresses near-term retail profitability

- Faster delivery options, expanded coverage, and better reliability

- Better customer service tooling and fraud prevention that reduce friction

- Improved seller tools and marketplace policies that increase selection and trust

The important point: the cash doesn’t need to be traced dollar-for-dollar from AWS to a specific retail initiative. What matters is that strong cash generation increases Amazon’s ability to keep investing through cycles when others would pull back.

Separate units, shared flexibility

AWS and retail are run as separate businesses in many operational ways (different customers, different economics, different priorities). That separation can create strategic flexibility: AWS can optimize for enterprise needs while retail optimizes for shopping and fulfillment. Yet at the corporate level, the combination can still support long-horizon decision-making—because one unit can produce steadier, higher-margin cash flows while another competes in a tougher margin environment.

Don’t oversimplify the causality

It’s tempting to say “AWS funds everything.” Reality is messier. Some improvements would have happened anyway, and some retail investments are driven by competition, not cloud profits. Treat the relationship as strategic support—not a single, direct pipe from cloud margin to every customer-facing upgrade.

Where the Flywheel Slows: Friction, Risk, and Constraints

Own the codebase

Keep full control by exporting source code when you’re ready to take the project further.

A flywheel works because each turn makes the next turn easier. But it’s not a perpetual-motion machine. When friction shows up—especially in trust and operations—the same compounding that helps you can start working against you.

Platform incentives can drift

Marketplaces are prone to incentive creep. As the platform matures, it’s tempting to squeeze more revenue out of the same customer attention—often through ads and pay-to-play placements.

That can lead to:

- Search results that feel “sponsored first, helpful second”

- More low-quality listings, confusing duplicates, or misleading titles

- Sellers optimizing for ranking tricks instead of real product quality

When customers have to work harder to find a good option, selection stops feeling like a benefit and starts feeling like noise. That’s flywheel friction.

Operational risk is real (and expensive)

Fast delivery is a promise that depends on thousands of moving parts. A few weak links can ripple across the system:

- Delivery delays from weather, labor shortages, or carrier issues

- Capacity planning mistakes (too much warehouse space, or not enough)

- Regional shocks that disrupt inventory flow and last-mile performance

Because speed is part of the product, operational hiccups aren’t just “back-end problems”—they directly affect customer behavior.

Scrutiny adds drag

As scale increases, so does attention from regulators, media, and the public. Investigations, compliance requirements, and policy changes can limit certain growth tactics or increase costs. Even when a company adapts, the time and focus spent managing scrutiny is time not spent improving the core experience.

Trust is the multiplier

The flywheel slows fastest when trust declines—counterfeits, inconsistent service, or a feeling that the platform prioritizes itself over the customer. Once trust drops, conversion drops, which reduces seller returns, which reduces selection and investment. Efficiency and trust aren’t side benefits; they’re the conditions that keep the wheel turning.

How to Apply Flywheel Thinking to Your Own Product

Flywheel thinking is a way to design growth so each improvement makes the next one easier. You don’t need Amazon’s scale—you need clarity about what you’re trying to make “feel effortless” for a customer, then build loops that reinforce that feeling.

A step-by-step checklist: define the core customer promise

Start with one sentence that’s specific and testable:

- For [who], we deliver [outcome] with [key constraint] (time, cost, reliability, simplicity).

Examples: “Get dinner on the table in 20 minutes,” “Ship fragile items without damage,” “Find a trusted local cleaner in under 5 minutes.” If you can’t measure whether you’re delivering it, it’s not a usable promise.

Identify your compounding loops

Look for loops that can compound over time:

- Acquisition loop: better product → more word-of-mouth → lower acquisition cost → more users → more feedback → better product.

- Retention loop: faster onboarding → earlier value → higher repeat rate → more revenue → more reinvestment in the experience.

- Supply loop (if you’re a marketplace): more demand → more sellers/providers → better selection → higher conversion → more demand.

- Ops loop: fewer defects/returns → lower cost to serve → ability to improve speed/quality → fewer defects.

Pick 3–5 measurable inputs

Avoid vanity metrics. Choose leading indicators you can influence weekly:

- Cost per order (or cost to serve)

- Delivery/fulfillment time (or time-to-value)

- Repeat rate (30/60/90-day)

- Defect rate (returns, support tickets, cancellations)

- Conversion rate (visit → purchase)

Common mistakes to avoid

Don’t design too many loops at once—one strong loop beats five weak ones. Don’t chase growth while ignoring quality, because defects create negative loops. And don’t underinvest in operations: the “boring” work (process, tooling, training) is often what unlocks speed and consistency.

A practical way to make this real is to shorten the “idea → shipped improvement” cycle so your flywheel can turn faster. For example, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai helps teams turn product requirements into working web, backend, or mobile apps through a chat interface—then iterate with snapshots/rollback and exportable source code. That kind of tooling directly supports the retention and ops loops: faster iteration → quicker customer value → more feedback → better product.

If you don’t have scale

Start with a small, high-control segment (one city, one category, one use case) where you can deliver the promise reliably. Use partnerships (3PLs, payment providers, marketplaces) to “rent” capabilities until volumes justify bringing them in-house.