Aug 28, 2025·8 min

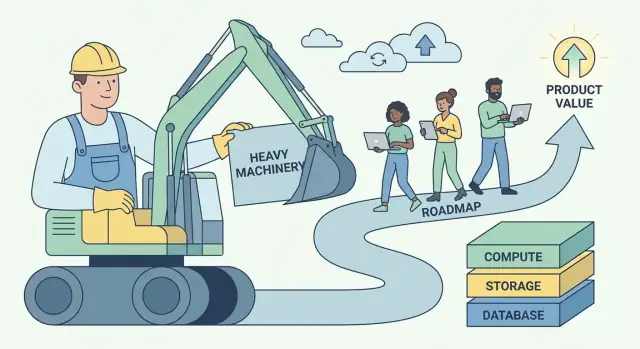

Andy Jassy’s AWS Playbook: Turning Heavy Lifting into Value

How Andy Jassy shaped AWS around “undifferentiated heavy lifting” and turned it into a repeatable model for building scalable software businesses and platforms.

What “Undifferentiated Heavy Lifting” Actually Means

“Undifferentiated heavy lifting” is a simple idea with a sharp edge: it’s the work you must do to run your software, but that doesn’t make customers choose you.

It includes tasks like provisioning servers, patching databases, rotating credentials, setting up monitoring, handling failover, scaling capacity, and chasing down production incidents caused by plumbing rather than product. These jobs are real, important, and often urgent—but they rarely create a unique experience for users.

Plain-language definition

If a task is:

- Necessary (you can’t avoid it if you want reliability)

- Repeatable (every team does a similar version of it)

- Not a competitive advantage (customers won’t pay more because you did it yourself)

…it’s undifferentiated heavy lifting.

Why the phrase resonated with builders and executives

Builders heard relief in it: permission to stop treating operational toil like a badge of honor. If everyone is reinventing the same deployment scripts and on-call runbooks, that’s not craftsmanship—it’s wasted focus.

Executives heard leverage: this category of work is expensive, scales poorly with headcount, and creates risk. Reducing it improves margins, reliability, and speed at the same time.

The business pattern this idea points to

AWS popularized a repeatable playbook:

- Remove toil by turning fragile, team-by-team operations into a service.

- Standardize the common parts so quality becomes consistent.

- Scale through automation and shared infrastructure.

- Reinvest the savings into better products and faster delivery.

This is bigger than cloud infrastructure—it’s “platform thinking” applied to any software business.

What to expect from this article

We’ll translate the concept into practical signals you can spot in your own product and team, show how managed services and internal platforms package operations as a product, and cover the real tradeoffs (control, cost, and lock-in). You’ll leave with a framework to decide what to build vs. buy—and how to turn undifferentiated work into compounding business value.

Andy Jassy’s Core Insight: Customers Want to Build, Not Babysit

Andy Jassy was one of the early leaders who helped turn Amazon’s internal infrastructure capabilities into what became AWS. His job wasn’t just “sell servers over the internet.” It was to notice a repeatable customer problem and package a solution that could scale across thousands of teams.

The real pain: operations steals attention from product

Most software teams don’t wake up excited to patch operating systems, provision capacity, rotate credentials, or recover from a failed disk. They do those things because they must—otherwise the app doesn’t run.

Jassy’s core insight was that a lot of this work is necessary but not differentiating. If you run an e-commerce site, a fintech app, or an internal HR tool, your customers value your features: faster checkout, better fraud detection, smoother onboarding. They rarely reward you for maintaining a perfectly tuned fleet of servers.

So the “babysitting” of infrastructure becomes a tax:

- It consumes time that could be spent shipping improvements.

- It forces teams to hire for skills they don’t want to specialize in.

- It increases risk because every company has to relearn the same operational lessons.

Why the timing mattered

This idea landed at a moment when demands were rising on all sides:

- Internet scale made traffic unpredictable; planning for peak was expensive.

- Startups needed to move quickly without building a data center team.

- Enterprise IT faced pressure to deliver faster while managing security and compliance.

The principle wasn’t “move everything to the cloud.” It was simpler: remove repeatable operational burdens so customers can spend more of their energy on what makes them different. That shift—time and attention back to building—became the foundation for a platform business.

Spotting Heavy Lifting in Your Own Product and Team

The first step is separating table-stakes work (needed to run a credible product) from differentiation (the reasons customers choose you).

Table stakes are not “unimportant.” They’re often critical to reliability and trust. But they rarely create preference on their own—especially once competitors can meet the same baseline.

Common “heavy lifting” signals

If you’re unsure what belongs in the undifferentiated bucket, look for work that is:

- Necessary, repetitive, and non-negotiable

- Costly when it breaks, but mostly invisible when it works

- Solved in broadly similar ways across companies

In software teams, this often includes:

- Managing servers or clusters

- Security patching and dependency updates

- Backups and disaster recovery drills

- Auto-scaling and capacity planning

- Basic monitoring, logging, and alerting

- On-call rotations for predictable failure modes

None of these are “bad.” The question is whether doing them yourself is part of your product’s value—or just the price of admission.

The simplest test: would customers pay for it?

A practical rule is:

“Would customers pay you for this specifically, or only expect it to be included?”

If the answer is “they’d only be angry if it’s missing,” you’re likely looking at undifferentiated heavy lifting.

A second test: if you removed this work tomorrow by adopting a managed service, would your best customers still value you for what remains? If yes, you’ve found a candidate for offloading, automating, or productizing.

“Undifferentiated” changes by market

What’s undifferentiated in one company can be core IP in another. A database vendor may differentiate on backup and replication. A fintech product probably shouldn’t. Your goal isn’t to copy someone else’s boundary—it’s to draw yours based on what your customers uniquely reward.

When you map your roadmap and ops work through this lens, you start seeing where time, talent, and attention are being spent just to stand still.

Why This Idea Creates Massive Business Value

“Undifferentiated heavy lifting” isn’t just a productivity hack. It’s a business model: take a problem that many companies must solve, but no one wants to differentiate on, and turn it into a service people happily pay for.

Commoditized problems are platform fuel

The best candidates are necessities with low strategic uniqueness: provisioning servers, patching databases, rotating credentials, scaling queues, managing backups. Every team needs them, almost every team would rather not build them, and the “right answer” is broadly similar across companies.

That combination creates a predictable market: high demand, repeating requirements, and clear success metrics (uptime, latency, compliance, recovery time). A platform can standardize the solution and keep improving it over time.

Economies of scale: spreading fixed costs across customers

Operational excellence has big fixed costs—SREs, security specialists, on-call rotations, audits, incident tooling, and 24/7 monitoring. When each company builds this alone, those costs get duplicated thousands of times.

A platform spreads those fixed investments across many customers. The per-customer cost drops as adoption rises, while the quality can rise because the provider can justify deeper specialization.

The reliability loop: specialization compounds uptime and security

When a service team runs the same component for many customers, they see more edge cases, detect patterns faster, and build better automation. Incidents become inputs: each failure hardens the system, improves playbooks, and tightens guardrails.

Security benefits similarly. Dedicated teams can invest in threat modeling, continuous patching, and compliance controls that would be hard for a single product team to sustain.

Pricing power: usage-based + trust + switching costs (carefully)

Platforms often earn pricing power through usage-based pricing: customers pay in proportion to value consumed, and can start small. Over time, trust becomes a differentiator—reliability and security make the service “default safe.”

Switching costs also rise as integrations deepen, but the healthiest version is earned, not trapped: better performance, better tooling, clearer billing, and fewer incidents. That’s what keeps customers renewing even when alternatives exist. For more on how this shows up in packaging and monetization, see /pricing.

The AWS Pattern: From Primitives to Managed Services

AWS didn’t win by offering “servers on the internet.” It won by repeatedly taking a hard operational problem, slicing it into simpler building blocks, and then re-bundling those blocks into services where AWS runs the day-2 work for you.

The repeatable ladder: primitive → service → managed service → platform

Think of it as a maturity ladder:

- Primitive: Raw ingredients you can assemble yourself (VMs, disks, networks)

- Service: A more opinionated API around a capability (object storage, load balancing)

- Managed service: AWS operates scaling, patching, backups, and failure recovery (databases, queues)

- Platform: A portfolio where services compose cleanly, with shared identity, billing, monitoring, and policy

Each step removes decisions, maintenance, and “what if it fails at 3 a.m.?” planning from the customer.

AWS examples (conceptual mapping)

AWS applied the same pattern across core categories:

-

Compute: Start with virtual machines (EC2). Move to higher-level compute where deployment and scaling become the default (e.g., managed container/serverless styles). The customer focuses on code and capacity intent, not host care.

-

Storage: From disks and file systems to object storage (S3). The abstraction shifts from “manage volumes” to “put/get objects,” while durability, replication, and scaling become AWS’s problem.

-

Databases: From “install a database on a VM” to managed databases (RDS, DynamoDB). Backups, patching, read replicas, and failover stop being a custom runbook and become configuration.

-

Messaging: From hand-rolled queues and workers to managed messaging (SQS/SNS). Delivery semantics, retries, and throughput tuning get standardized so teams can build workflows instead of infrastructure.

Why abstractions reduce cognitive load

Managed services reduce cognitive load in two ways:

- Fewer moving parts to reason about. Your architecture diagram shrinks from “instances + scripts + cron + alerting + backups” to “service + settings.”

- Fewer failure modes you must own. You still design for resilience, but you’re no longer responsible for the mechanics of patching, clustering, and routine recovery.

The result is faster onboarding, fewer bespoke runbooks, and more consistent operations across teams.

Takeaway checklist (reuse this in your own product)

- What are customers building that’s necessary but not differentiating?

- Can you turn their recurring runbooks into a single, stable API?

- Which tasks can you make default (backups, scaling, upgrades) instead of optional?

- Are the “sharp edges” moved behind sensible limits and guardrails?

- Can multiple teams reuse it without expert knowledge?

- Does it compose with the rest of your system (identity, monitoring, billing, policies)?

Packaging Operations as a Product

Make building pay back

Earn credits by sharing what you build with Koder.ai or referring a teammate.

A useful way to read AWS is: it doesn’t just sell technology, it sells operations. The “product” isn’t only an API endpoint—it’s everything required to run that capability safely, predictably, and at scale.

APIs vs. self-service vs. full management

An API gives you building blocks. You can provision resources, but you still design the guardrails, monitor failures, handle upgrades, and answer “who changed what?”

Self-service adds a layer customers can use without filing tickets: consoles, templates, sensible defaults, and automated provisioning. The customer still owns most day-2 work, but it’s less manual.

Full management is when the provider takes on the ongoing responsibilities: patching, scaling, backups, failover, and many classes of incident response. Customers focus on configuring what they want, not how it’s kept running.

The “boring” features customers can’t live without

The capabilities people rely on daily are rarely flashy:

- IAM and permissions: who can do what, and how access is audited

- Billing and cost visibility: budgets, invoices, tags, and alerts

- Quotas and rate limits: protections that prevent accidents—and set clear expectations

These aren’t side quests. They’re part of the promise customers buy.

Operations as a first-class feature

What makes a managed service feel “real” is the operational package around it: clear documentation, predictable support channels, and explicit service limits. Good docs reduce support load, but more importantly they reduce customer anxiety. Published limits and quota processes turn surprises into known constraints.

When you package operations as a product, you’re not only shipping features—you’re shipping confidence.

The Organizational Design That Makes Platforms Work

A platform succeeds or fails less on architecture diagrams and more on org design. If teams don’t have clear customers, incentives, and feedback loops, the “platform” turns into a backlog of opinions.

Internal teams as the first customers (dogfooding)

The fastest way to keep a platform honest is to make internal product teams the first—and loudest—customers. That means:

- Platform teams ship to internal teams through the same interfaces and docs external users would see.

- Adoption is earned (via usefulness), not mandated (via policy).

- Support tickets, incident reviews, and roadmap decisions treat internal teams like real customers, with clear SLAs.

Dogfooding forces clarity: if your own teams avoid the platform, external customers will too.

Central vs. federated platform models

Two org patterns show up repeatedly:

Central platform team: one team owns the core building blocks (CI/CD, identity, observability, runtime, data primitives). This is great for consistency and economies of scale, but risks becoming a bottleneck.

Federated model: a small central team sets standards and shared primitives, while domain teams own “platform slices” (e.g., data platform, ML platform). This improves speed and domain fit, but requires strong governance to avoid fragmentation.

Metrics that matter (and platform pitfalls)

Useful platform metrics are outcomes, not activity:

- Lead time to production (how quickly teams can ship)

- Availability and incident rate of platform services

- Cost per workload (unit economics, not total spend)

Common pitfalls include misaligned incentives (platform judged on feature count, not adoption), over-design (building for hypothetical scale), and success measured by mandates rather than voluntary usage.

The Compounding Flywheel Behind Platform Growth

Go live with confidence

Put your app on a custom domain when you are ready to share it.

Platforms grow differently than one-off products. Their advantage isn’t just “more features”—it’s a feedback loop where every new customer makes the platform easier to run, easier to improve, and harder to ignore.

The flywheel in plain terms

More customers → more real-world usage data → clearer patterns about what breaks, what’s slow, what’s confusing → better defaults and automation → a better service for everyone → more customers.

AWS benefited from this because managed services turn operational toil into a shared, repeatable capability. When the same problems show up across thousands of teams (monitoring, patching, scaling, backups), the provider can fix them once and distribute the improvement to all customers.

Why standardization accelerates innovation

Standardization is often framed as “less flexibility,” but for platforms it’s a speed multiplier. When infrastructure and operations become consistent—one set of APIs, one approach to identity, one way to observe systems—builders stop reinventing the basics.

That reclaimed time turns into higher-level innovation: better product experiences, faster experiments, and new capabilities on top of the platform (not beside it). Standardization also reduces the cognitive load for teams: fewer decisions, fewer failure modes, faster onboarding.

The long-term bet: compounding at scale

Small improvements compound when they’re applied to millions of requests and thousands of customers. A 2% reduction in incident rate, a slightly better autoscaling algorithm, or a clearer default configuration doesn’t just help one company—it upgrades the platform’s baseline.

How Heavy Lifting Removal Translates into Faster Shipping

Removing undifferentiated heavy lifting doesn’t just save hours—it changes how teams behave. When the “keep-the-lights-on” work shrinks, roadmaps stop being dominated by maintenance chores (patching servers, rotating keys, babysitting queues) and start reflecting product bets: new features, better UX, more experiments.

The second-order effects that compound

Less toil creates a chain reaction:

- Onboarding gets easier. New engineers can ship in days instead of learning a maze of internal runbooks.

- Incidents drop—and get simpler. Fewer bespoke systems means fewer weird failure modes and fewer 3 a.m. escalations.

- Releases become routine. Teams can release more often because deployment, rollback, and monitoring are standardized.

Speed vs. thrash: shipping vs. firefighting

Real speed is a steady cadence of small, predictable releases. Thrash is motion without progress: urgent bug fixes, emergency infra work, and “quick” changes that create more debt.

Heavy lifting removal reduces thrash because it eliminates entire categories of work that repeatedly interrupt planned delivery. A team that used to spend 40% of its time reacting can redirect that capacity into features—and keep it there.

Practical SaaS examples

Authentication: Instead of maintaining password storage, MFA flows, session handling, and compliance audits yourself, use a managed identity provider. Result: fewer security incidents, faster SSO rollouts, and less time spent updating auth libraries.

Payments: Offload payment processing, tax/VAT handling, and fraud checks to a specialized provider. Result: faster expansion into new regions, fewer chargeback surprises, and less engineering time tied up in edge cases.

Observability: Standardize on a managed logging/metrics/tracing stack rather than homegrown dashboards. Result: quicker debugging, clearer ownership during incidents, and confidence to deploy more frequently.

The pattern is simple: when operations become a product you consume, engineering time returns to building what customers actually pay for.

Tradeoffs: Lock-In, Control, and Cost

Removing undifferentiated heavy lifting is not a free lunch. AWS-style managed services often trade day-to-day effort for tighter coupling, fewer knobs, and bills that can surprise you.

The three big tradeoffs

Vendor lock-in. The more you rely on proprietary APIs (queues, IAM policies, workflow engines), the harder it is to move later. Lock-in isn’t always bad—it can be the price of speed—but you should choose it deliberately.

Loss of control. Managed services reduce your ability to tune performance, choose exact versions, or debug deep infrastructure issues. When an outage happens, you may be waiting on a provider’s timeline.

Cost surprises. Consumption pricing rewards efficient usage, but it can punish growth, chatty architectures, and “set-and-forget” defaults. Teams often discover costs after they ship.

When building is rational

Building (or self-hosting) can be the right call when you have unique requirements (custom latency, special data models), massive scale where unit economics flip, or compliance/data residency constraints that managed services can’t satisfy.

Guardrails that keep you fast without getting trapped

Design service boundaries: wrap provider calls behind your own interface so you can swap implementations.

Maintain a portability plan: document what would be hardest to migrate, and keep a “minimum viable exit” path (even if it’s slow).

Add cost monitoring early: budgets, alerts, tagging, and regular reviews of top spenders.

Copyable decision matrix

| Question | Prefer Managed | Prefer Build/Self-host |

|---|---|---|

| Is this a differentiator for customers? | No | Yes |

| Can we tolerate provider limits/opinionated behavior? | Yes | No |

| Do we need special compliance/control? | No | Yes |

| Is speed-to-market the top priority? | Yes | No |

| Is cost predictable at our usage pattern? | Yes | No |

A Practical Framework to Apply the Pattern in Any Software Business

Keep your exit option

Get the source code export when you want full control of your stack.

You don’t need to run a hyperscale cloud to use the “remove undifferentiated heavy lifting” playbook. Any software team—SaaS, internal platforms, data products, even support-heavy tools—has recurring work that is expensive, error-prone, and not a true differentiator.

A step-by-step method (from toil to product)

-

List recurring toil: Write down the repeated tasks people do to keep things running—manual deployments, ticket triage, data backfills, access requests, incident handoffs, brittle scripts, “tribal knowledge” checklists.

-

Quantify it: For each item, estimate frequency, time spent, and failure cost. A simple score works: hours/week + severity of mistakes + number of teams affected. This turns vague pain into a ranked backlog.

-

Standardize the workflow: Before you automate, define the “one best way.” Create a template, golden path, or minimal set of supported options. Reducing variation is often the biggest win.

-

Automate and package: Build self-serve tooling (APIs, UI, runbooks-as-code) and treat it like a product: clear ownership, versioning, docs, and a support model.

One modern variant of this approach is “vibe-coding” platforms that turn repetitive scaffolding and day-1 setup into a guided workflow. For example, Koder.ai lets teams create web, backend, and mobile apps from a chat interface (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile) and then export source code or deploy/host—useful when your bottleneck is getting from idea to a reliable baseline without redoing the same project wiring every time.

Start with one workflow (and prove the loop)

Pick a single, high-frequency workflow where success is measurable—deployments, data pipelines, or support tooling are good candidates. Aim for a quick win: fewer steps, fewer pages, fewer approvals, faster recovery.

Sequencing: what to do first

- Reliability first: Make the process consistent and safe.

- Features second: Add capabilities users actually request.

- Optimization third: Tune cost and performance after usage stabilizes.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps

The reusable lesson from Andy Jassy’s AWS strategy is simple: you win by making the common work disappear. When customers (or internal teams) stop spending time on setup, patching, scaling, and incident babysitting, they get to spend that time on what actually differentiates them—features, experiences, and new bets.

The takeaway to keep front and center

“Undifferentiated heavy lifting” isn’t just “hard work.” It’s work that many teams repeat, that must be done to operate reliably, but that rarely earns unique credit in the market. Turning that work into a product—especially a managed service—creates value twice: you lower the cost of running software and you increase the rate of shipping.

Pick one thing to remove this quarter

Don’t start with a grand platform rewrite. Start with one recurring pain that shows up in tickets, on-call pages, or sprint spillover. Good candidates:

- Environment setup that varies by team

- Manual releases and rollbacks

- Repeating security reviews for the same patterns

- Scaling/monitoring defaults that everyone re-discovers the hard way

Choose one, define “done” in plain language (e.g., “a new service can deploy safely in 15 minutes”), and ship the smallest version that eliminates the repeat work.

Related internal reads

If you want more practical patterns on platform thinking and build-vs.-buy decisions, browse /blog. If you’re evaluating what to standardize versus what to offer as an internal (or external) paid capability, /pricing can help frame packaging and tiers.

Next step: a simple platform backlog

This week, do three things: audit where time is lost to repeat ops work, prioritize by frequency × pain × risk, and build a simple platform backlog with 3–5 items you can deliver incrementally.