Jul 20, 2025·8 min

API Evolution & Backward Compatibility in AI Backends

Learn how AI-generated backends evolve APIs safely: versioning, compatible changes, migrations, deprecation steps, and tests that prevent breaking clients.

Learn how AI-generated backends evolve APIs safely: versioning, compatible changes, migrations, deprecation steps, and tests that prevent breaking clients.

API evolution is the ongoing process of changing an API after it’s already being used by real clients. That might mean adding fields, adjusting validation rules, improving performance, or introducing new endpoints. It matters most once clients are in production, because even a “small” change can break a mobile app release, an integration script, or a partner workflow.

A change is backward compatible if existing clients keep working without any updates.

For example, suppose your API returns:

{ "id": "123", "status": "processing" }

Adding a new optional field is typically backward compatible:

{ "id": "123", "status": "processing", "estimatedSeconds": 12 }

Older clients that ignore unknown fields will continue working. By contrast, renaming status to state, changing a field’s type (string → number), or making an optional field required are common breaking changes.

An AI-generated backend isn’t just a code snippet. In practice it includes:

Because AI can regenerate parts of the system quickly, the API can “drift” unless you intentionally manage changes.

This is especially true when you generate entire apps from a chat-driven workflow. For example, Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform) can create web, server, and mobile applications from a simple chat—often with React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, and Flutter for mobile. That speed is great, but it makes contract discipline (and automated diff/testing) even more important so a regenerated release doesn’t accidentally change what clients depend on.

AI can automate a lot: producing OpenAPI specs, updating boilerplate code, suggesting safe defaults, and even drafting migration steps. But human review is still essential for decisions that affect client contracts—what changes are allowed, which fields are stable, and how to handle edge cases and business rules. The goal is speed with predictable behavior, not speed at the cost of surprises.

APIs rarely have a single “client.” Even a small product can have multiple consumers that depend on the same endpoints behaving the same way:

When an API breaks, the cost isn’t just developer time. Mobile users may be stuck on older app versions for weeks, so a breaking change can turn into a long tail of errors and support tickets. Partners might experience downtime, miss data, or halt critical workflows—often with contractual or reputational consequences. Internal services can silently fail and create messy backlogs (for example, missing events or incomplete records).

AI-generated backends add a twist: code can change quickly and frequently, sometimes in large diffs, because generation is optimized for producing working code—not for preserving behavior across time. That speed is valuable, but it also increases the risk of accidental breaking changes (renamed fields, different defaults, stricter validation, new auth requirements).

That’s why backward compatibility needs to be a deliberate product decision, not a best-effort habit. The practical approach is to define a predictable change process where the API is treated like a product interface: you can add capabilities, but you don’t surprise existing clients.

A useful mental model is to treat the API contract (for example, an OpenAPI spec) as the “source of truth” for what clients can rely on. Generation then becomes an implementation detail: you can regenerate the backend, but the contract—and the promises it makes—stays stable unless you intentionally version and communicate changes.

When an AI system can generate or modify backend code quickly, the only reliable anchor is the API contract: the written description of what clients can call, what they must send, and what they can expect back.

A contract is a machine-readable spec such as:

This contract is what you promise to external consumers—even if the implementation behind it changes.

In a contract-first workflow, you design or update the OpenAPI/GraphQL schema first, then generate server stubs and fill in logic. This is usually safer for compatibility because changes are intentional and reviewable.

In a code-first workflow, the contract is produced from code annotations or runtime introspection. AI-generated backends often lean code-first by default, which is fine—as long as the generated contract is treated as an artifact to review, not an afterthought.

A practical hybrid is: let the AI propose code changes, but require that it also updates (or regenerates) the contract, and treat contract diffs as the main change signal.

Store your API specs in the same repo as the backend and review them via pull requests. A simple rule: no merge unless the contract change is understood and approved. This makes backward-incompatible edits visible early, before they reach production.

To reduce drift, generate server stubs and client SDKs from the same contract. When the contract updates, both sides update together—making it much harder for an AI-generated implementation to accidentally “invent” behavior that clients weren’t built to handle.

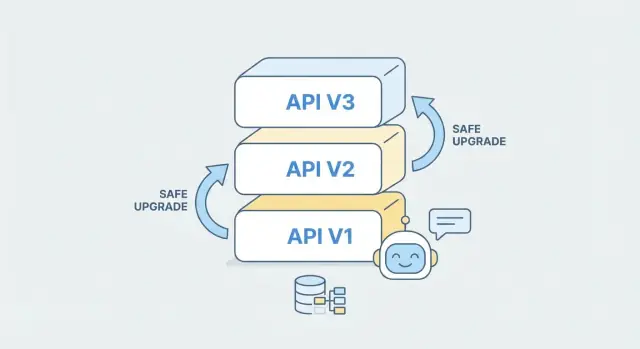

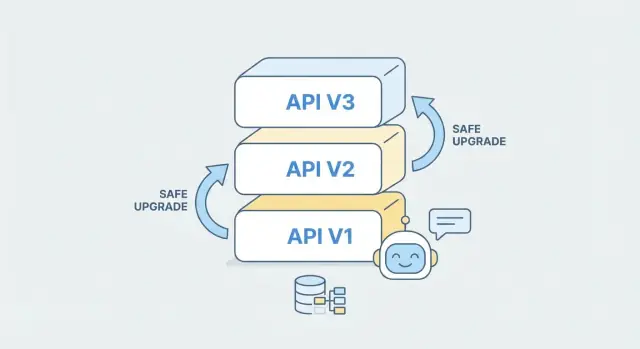

API versioning isn’t about predicting every future change—it’s about giving clients a clear, stable way to keep working while you improve the backend. In practice, the “best” strategy is the one your consumers understand instantly and your team can apply consistently.

URL versioning puts the version in the path, like /v1/orders and /v2/orders. It’s visible in every request, easy to debug, and works well with caching and routing.

Header versioning keeps URLs clean and moves the version into a header (for example, Accept: application/vnd.myapi.v2+json). This can be elegant, but it’s less obvious during troubleshooting and can be missed in copy-pasted examples.

Query parameter versioning uses something like /orders?version=2. It’s straightforward, but can get messy when clients or proxies strip/alter query strings, and it’s easier for people to accidentally mix versions.

For most teams—especially when you want simple client understanding—default to URL versioning. It’s the least surprising approach, easy to document, and makes it obvious which version a given SDK, mobile app, or partner integration is calling.

When you use AI to generate or extend a backend, treat each version as a separate “contract + implementation” unit. You can scaffold a new /v2 from an updated OpenAPI spec while keeping /v1 intact, then share business logic underneath where possible. This reduces risk: existing clients keep working, while new clients adopt v2 intentionally.

Versioning only works if your docs keep up. Maintain versioned API docs, keep examples consistent per version, and publish a changelog that clearly states what changed, what’s deprecated, and migration notes (ideally with side-by-side request/response examples).

When an AI-generated backend updates, the safest way to think about compatibility is: “Will an existing client still work without changes?” Use the checklist below to classify changes before you ship them.

These changes typically don’t break existing clients because they don’t invalidate what clients already send or expect:

middleName or metadata). Existing clients should keep working as long as they don’t require an exact field set.Treat these as breaking unless you have strong evidence otherwise:

nullable → non-nullable).Encourage clients to be tolerant readers: ignore unknown fields and handle unexpected enum values gracefully. This allows the backend to evolve by adding fields without forcing client updates.

A generator can prevent accidental breaking changes by policy:

API changes are what clients see: request/response shapes, field names, validation rules, and error behavior. Database changes are what your backend stores: tables, columns, indexes, constraints, and data formats. They’re related, but not identical.

A common mistake is treating a database migration as “internal only.” In AI-generated backends, the API layer is often generated from the schema (or tightly coupled to it), so a schema change can silently become an API change. That’s how older clients break even when you didn’t intend to touch the API.

Use a multi-step approach that keeps both old and new code paths working during rolling upgrades:

This pattern avoids “big bang” releases and gives you rollback options.

Old clients often assume a field is optional or has a stable meaning. When adding a new non-null column, choose between:

Be careful: a DB default doesn’t always help if your API serializer still emits null or changes validation rules.

AI tools can draft migration scripts and even suggest backfills, but you still need human validation: confirm constraints, check performance (locks, index builds), and run migrations against staging data to ensure older clients keep working.

Feature flags let you change behavior without changing the endpoint shape. That’s especially useful in AI-generated backends, where internal logic may be regenerated or optimized frequently, but clients still depend on consistent requests and responses.

Instead of releasing a “big switch,” you ship the new code path disabled by default, then turn it on gradually. If something goes wrong, you turn it off—without rushing an emergency redeploy.

A practical rollout plan usually combines three techniques:

For APIs, the key is to keep responses stable while you experiment internally. You can swap implementations (new model, new routing logic, new DB query plan) while returning the same status codes, field names, and error formats the contract promises. If you need to add new data, prefer additive fields that clients can ignore.

Imagine a POST /orders endpoint that currently accepts phone in many formats. You want to enforce E.164 formatting, but tightening validation can break existing clients.

A safer approach:

strict_phone_validation).This pattern lets you move toward better data quality without turning a backward-compatible API into an accidental breaking change.

Deprecation is the “polite exit” for old API behavior: you stop encouraging it, you warn clients early, and you give them a predictable path to move forward. Sunsetting is the final step: an old version is turned off on a published date. For AI-generated backends—where endpoints and schemas can evolve quickly—having a strict retirement process is what keeps updates safe and trust intact.

Use semantic versioning at the API contract level, not just in your repo.

Put this definition in your docs once, then apply it consistently. It prevents “silent majors” where an AI-assisted change looks small but breaks a real client.

Pick a default policy and stick to it so users can plan. A common approach:

If you’re unsure, choose a slightly longer window; the cost of keeping a version alive briefly is usually lower than the cost of emergency client migrations.

Rely on multiple channels because not everyone reads release notes.

Deprecation: true and Sunset: Wed, 31 Jul 2026 00:00:00 GMT, plus a Link to migration docs.Also include deprecation notices in changelogs and status updates so procurement and ops teams see them.

Keep old versions running until the sunset date, then disable them deliberately—not gradually via accidental breakage.

On sunset:

410 Gone) with a message pointing to the newest version and migration page.Most importantly, treat sunsetting as a scheduled change with owners, monitoring, and a rollback plan. That discipline is what makes frequent evolution possible without surprising clients.

AI-generated code can change quickly—and sometimes in surprising places. The safest way to keep clients working is to test the contract (what you promise externally), not just the implementation.

A practical baseline is a contract test that compares the previous OpenAPI spec to the newly generated one. Treat it like a “before vs. after” check:

Many teams automate an OpenAPI diff in CI so no generated change can be deployed without review. This is especially useful when prompts, templates, or model versions shift.

Consumer-driven contract testing flips the perspective: instead of the backend team guessing how clients use the API, each client shares a small set of expectations (the requests it sends and the responses it relies on). The backend must prove it still satisfies those expectations before release.

This works well when you have multiple consumers (web app, mobile app, partners) and you want updates without coordinating every deployment.

Add regression tests that lock down:

If you publish an error schema, test it explicitly—clients often parse errors more than we’d like.

Combine OpenAPI diff checks, consumer contracts, and shape/error regression tests into a CI gate. If a generated change fails, the fix is usually to adjust the prompt, generation rules, or a compatibility layer—before users notice.

When clients integrate with your API, they usually don’t “read” error messages—they react to error shapes and codes. A typo in a human-friendly message is annoying but survivable; a changed status code, missing field, or renamed error identifier can turn a recoverable situation into a broken checkout, a failed sync, or an infinite retry loop.

Aim to keep a consistent error envelope (the JSON structure) and a stable set of identifiers clients can rely on. For example, if you return { code, message, details, request_id }, don’t remove or rename those fields in a new version. You can improve wording in message freely, but keep code semantics stable and documented.

If you already have multiple formats in the wild, resist the urge to “clean it up” in place. Instead, add a new format behind a version boundary or a negotiation mechanism (e.g., Accept header), while continuing to support the old one.

New error codes are sometimes necessary (new validation rules, new authorization checks), but you should add them in a way that doesn’t surprise existing integrations.

A safe approach:

VALIDATION_ERROR, don’t replace it with INVALID_FIELD overnight.code, but also include backward-compatible hints in details (or keep mapping to the older generalized code for older versions).message.Crucially, never change the meaning of an existing code. If NOT_FOUND used to mean “resource doesn’t exist,” don’t start using it for “access denied” (that’s a 403).

Backward compatibility is also about “same request, same result.” Seemingly small default changes can break clients that never explicitly set parameters.

Pagination: don’t change default limit, page_size, or cursor behavior without versioning. Switching from page-based to cursor-based pagination is a breaking change unless you keep both paths.

Sorting: default sort order should be stable. Changing from created_at desc to relevance desc can reorder lists and break UI assumptions or incremental sync.

Filtering: avoid altering implicit filters (e.g., suddenly excluding “inactive” items by default). If you need a new behavior, add an explicit flag like include_inactive=true or status=all.

Some compatibility issues aren’t about endpoints—they’re about interpretation.

"9.99" to 9.99 (or vice versa) in place.include_deleted=false or send_email=true should not flip. If you must change a default, require the client to opt in via a new parameter.For AI-generated backends in particular, lock these behaviors down with explicit contracts and tests: the model may “improve” responses unless you enforce stability as a first-class requirement.

Backward compatibility isn’t something you verify once and forget. With AI-generated backends, behavior can change faster than in hand-built systems, so you need feedback loops that show who is using what, and whether an update is harming clients.

Start by tagging every request with an explicit API version (path like /v1/..., header like X-Api-Version, or the negotiated schema version). Then collect metrics segmented by that version:

This lets you notice, for example, that /v1/orders is only 5% of traffic but 70% of errors after a rollout.

Instrument your API gateway or application to log what clients actually send and which routes they’re calling:

/v1/legacy-search)If you control SDKs, add a lightweight client identifier + SDK version header to spot outdated integrations.

When errors jump, you want to answer: “Which deployment changed behavior?” Correlate spikes with:

Keep rollbacks boring: always be able to redeploy the previous generated artifact (container/image) and flip traffic back via your router. Avoid rollbacks that require data reversals; if schema changes are involved, prefer additive DB migrations so older versions keep working while you revert the API layer.

If your platform supports environment snapshots and fast rollback, use them. For instance, Koder.ai includes snapshots and rollback as part of its workflow, which pairs naturally with “expand → migrate → contract” database changes and gradual API rollouts.

AI-generated backends can change quickly—new endpoints appear, models shift, and validations tighten. The safest way to keep clients stable is to treat API changes like a small, repeatable release process rather than “one-off edits.”

Write down the “why,” the intended behavior, and the exact contract impact (fields, types, required/optional, error codes).

Mark it as compatible (safe) or breaking (requires client changes). If unsure, assume breaking and design a compatibility path.

Decide how you’ll support old clients: aliases, dual-write/dual-read, default values, tolerant parsing, or a new version.

Add the change with feature flags or configuration so you can roll it out gradually and roll back quickly.

Run automated contract checks (e.g., OpenAPI diff rules) plus golden “known client” request/response tests to catch behavior drift.

Every release should include: updated reference docs in /docs, a short migration note when relevant, and a changelog entry that states what changed and whether it’s compatible.

Announce deprecations with dates, add response headers/warnings, measure remaining usage, then remove after the sunset window.

If you want to rename last_name to family_name:

family_name.family_name and keep last_name as an alias field).last_name as deprecated, and set a removal date.If your offering includes plan-based support or long-term version support, call that out clearly on /pricing.

Backward compatibility means existing clients keep working without any changes. In practice, you can usually:

You usually can’t rename/remove fields, change types, or tighten validation without breaking someone.

Treat changes as breaking if they require any deployed client to update. Common breaking changes include:

status → state)Use an API contract as your anchor, typically:

Then:

This keeps AI regeneration from silently changing client-facing behavior.

In contract-first, you update the spec first, then generate/implement code. In code-first, the spec is generated from code.

A practical hybrid for AI workflows:

Automate an OpenAPI diff check in CI and fail builds when changes look breaking, such as:

Allow merges only when either (a) the change is confirmed compatible, or (b) you bump to a new major version.

URL versioning (e.g., /v1/orders, /v2/orders) is usually the least surprising:

Header or query versioning can work, but it’s easier for clients and support teams to miss during troubleshooting.

Assume some clients are strict. Safer patterns:

If you must change meaning or remove an enum value, do it behind a new version.

Use “expand → migrate → contract” so old and new code can run during rollouts:

This reduces downtime risk and keeps rollback possible.

Feature flags let you change internal behavior while keeping the request/response shape stable. A practical rollout:

This is especially useful for stricter validation or performance rewrites.

Make deprecation hard to miss and time-bounded:

Deprecation: true, Sunset: <date>, Link: </docs/api/v2/migration>)410 Gone) with migration guidance