May 12, 2025·8 min

Arm’s Licensing Model: Scaling CPU IP via Ecosystem Fit

How Arm scaled by licensing CPU IP across mobile and embedded—and why software, tools, and compatibility can matter more than owning fabs.

How Arm scaled by licensing CPU IP across mobile and embedded—and why software, tools, and compatibility can matter more than owning fabs.

Arm didn’t become influential by shipping boxes of finished chips. Instead, it scaled by selling CPU designs and compatibility—the pieces other companies can build into their own processors, in their own products, on their own manufacturing timelines.

“CPU IP licensing” is essentially selling a proven set of blueprints plus the legal right to use them. A partner pays Arm to use a particular CPU design (and related technology), then integrates it into a larger chip that might also include graphics, AI blocks, connectivity, security features, and more.

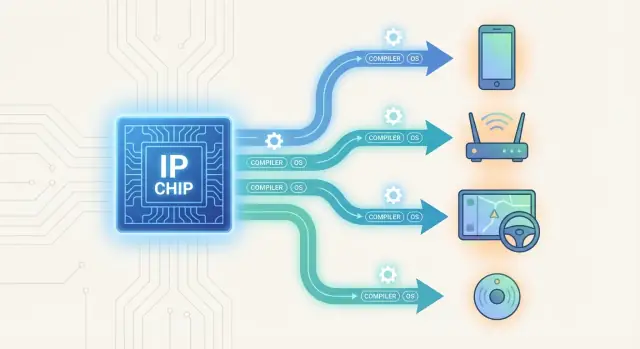

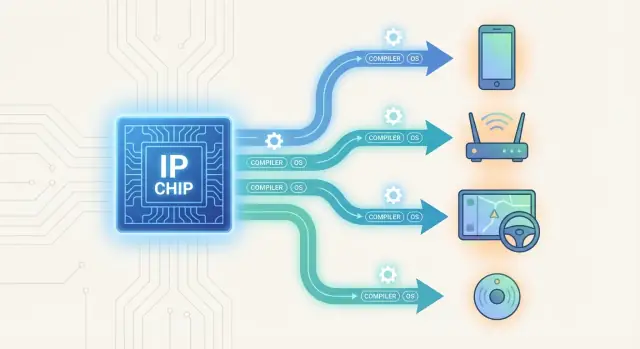

The division of labor looks like this:

In semiconductors, “better manufacturing” can be a strong advantage—but it’s often temporary, expensive, and hard to extend across many markets. Compatibility, on the other hand, compounds. When lots of devices share a common foundation (instruction set, tools, operating system support), developers, manufacturers, and customers benefit from predictable behavior and a growing pool of software.

Arm is a clear example of how ecosystem fit—shared standards, toolchains, and a large partner network—can become more valuable than owning factories.

We’ll keep the history high-level, explain what Arm actually licenses, and show how this model spread across mobile and embedded products. Then we’ll break down the economics in plain terms, the trade-offs and risks, and end with practical platform lessons you can apply even outside chips.

For a quick preview of the business mechanics, jump to /blog/the-licensing-economics-plain-english-version.

Arm doesn’t “sell chips” in the usual sense. What it sells is permission—through licenses—to use Arm intellectual property (IP) in chips that other companies design and manufacture.

It helps to separate three layers that often get mixed up:

Arm’s licensing mostly lives in the first two layers: the rules (ISA) and/or a ready-to-integrate CPU design (core). The licensee builds the full SoC around it.

Most discussions boil down to two broad models:

Depending on the agreement, licensees typically get RTL (hardware design code), reference configurations, documentation, validation collateral, and engineering support—the ingredients needed to integrate and ship a product.

What Arm typically does not do is manufacture chips. That part is handled by the licensee and their chosen foundry plus packaging/test partners.

Chipmaking is expensive, slow, and full of “unknown unknowns.” A licensing model scales because it lets many companies reuse a CPU design that’s already been validated—functionally, electrically, and often in silicon. Reuse reduces risk (fewer surprises late in the schedule) and cuts time to market (less design from scratch, fewer bugs to chase).

A modern CPU core is one of the hardest blocks to get right. When a proven core is available as IP, partners can concentrate effort on differentiation:

This creates parallel innovation: dozens of teams can build distinct products on top of the same foundation, instead of waiting on one company’s roadmap.

In a vertically integrated approach, one company designs the CPU, designs the SoC, validates it, and ships the final chip (and sometimes the devices too). That can produce great results—but scaling is constrained by one organization’s engineering bandwidth, manufacturing access, and ability to serve many niches at once.

Licensing flips that. Arm focuses on the reusable “core” problems, while partners compete and specialize around it.

As more companies ship compatible CPU designs, developers and tool vendors invest more heavily in compilers, debuggers, operating systems, libraries, and optimizations. Better tools make it easier to ship the next device, which increases adoption again—an ecosystem flywheel that a single chipmaker struggles to match alone.

Mobile chips grew up under harsh constraints: tiny devices, no fans, limited surface area to shed heat, and a battery users expect to last all day. That combination forces CPU designers to treat power and thermals as first-class requirements, not afterthoughts. A phone can’t “borrow” extra watts for long without getting hot, throttling performance, and draining the battery.

In that environment, the winning metric isn’t raw benchmark glory—it’s performance per watt. A CPU that is slightly slower on paper but sips power can deliver a better real user experience because it sustains speed without overheating.

That’s a big reason Arm licensing took off in smartphones: Arm’s instruction set architecture (ISA) and core designs aligned with the idea that efficiency is the product.

Arm’s CPU IP licensing also solved a market problem: phone makers wanted variety and competition among chip suppliers, but they couldn’t afford a fragmented software world.

With Arm, multiple chip design partners could build different mobile processors—adding their own GPUs, modems, AI blocks, memory controllers, or power-management techniques—while staying compatible at the CPU level.

That compatibility mattered to everyone: app developers, OS vendors, and tool makers. When the underlying target stays consistent, toolchains, debuggers, profilers, and libraries improve faster—and cost less to support.

Smartphones shipped in massive volumes, which amplified the benefits of standardization. High volume justified deeper optimization for Arm-based chips, encouraged broader software and tools support, and made Arm licensing the “safe default” for mobile.

Over time, that feedback loop helped CPU IP licensing outcompete approaches that relied mostly on a single company’s manufacturing advantage instead of ecosystem compatibility.

“Embedded” isn’t one market—it’s a catch‑all for products where the computer is inside something else: home appliances, industrial controllers, networking gear, automotive systems, medical devices, and a huge range of IoT hardware.

What these categories share is less about features and more about constraints: tight power budgets, fixed costs, and systems that have to behave predictably.

Embedded products often ship for many years, sometimes a decade or more. That means reliability, security patching, and supply continuity matter as much as peak performance.

A CPU foundation that stays compatible across generations reduces churn. Teams can keep the same core software architecture, reuse libraries, and backport fixes without rewriting everything for each new chip.

When a product line must be maintained long after launch, “it still runs the same code” becomes a business advantage.

Using a widely adopted Arm instruction set across many devices makes staffing and operations easier:

This is especially helpful for companies shipping multiple embedded products at once—each team doesn’t need to reinvent a platform from scratch.

Embedded portfolios rarely have a single “best” device. They have tiers: low-cost sensors, midrange controllers, and high-end gateways or automotive compute units.

Arm’s ecosystem lets partners pick cores (or design their own) that fit different power and performance targets while keeping familiar software foundations.

The result is a coherent product family: different price points and capabilities, but compatible development workflows and a smoother upgrade path.

A great factory can make chips cheaper. A great ecosystem can make products cheaper to build, ship, and maintain.

When many devices share a compatible CPU foundation, the advantage isn’t just performance-per-watt—it’s that apps, operating systems, and developer skills transfer across products. That transferability becomes a business asset: less time rewriting, fewer surprise bugs, and a bigger hiring pool of engineers who already know the tools.

Arm’s long-term ISA and ABI stability means software written for one Arm-based device often keeps working—sometimes with only a recompile—on newer chips and different vendors’ silicon.

That stability reduces hidden costs that pile up across generations:

Even small changes matter. If a company can move from “Chip A” to “Chip B” without rewriting drivers, revalidating the whole codebase, or retraining the team, it can switch suppliers faster and ship on schedule.

Compatibility isn’t only about the CPU core—it’s about everything that surrounds it.

Because Arm is widely targeted, many third-party components arrive “already done”: crypto libraries, video codecs, ML runtimes, networking stacks, and cloud agent SDKs. Silicon vendors also ship SDKs, BSPs, and reference code designed to feel familiar to developers who’ve worked on other Arm platforms.

Manufacturing scale can reduce unit cost. Ecosystem compatibility reduces total cost—engineering time, risk, and time-to-market—often by even more.

Arm licensing isn’t only about getting a CPU core or an instruction set architecture. For most teams, the make-or-break factor is whether they can build, debug, and ship software quickly on day one. That’s where ecosystem tooling depth quietly compounds over time.

A new chip vendor can have a great microarchitecture, but developers still ask basic questions: Can I compile my code? Can I debug crashes? Can I measure performance? Can I test without hardware?

For Arm-based platforms, the answer is usually “yes” out of the box because the tooling is widely standardized:

With CPU IP licensing, many different companies ship Arm-compatible chips. If each required a unique toolchain, every new vendor would feel like a fresh platform port.

Instead, Arm compatibility means developers can often reuse existing build systems, CI pipelines, and debugging workflows. That reduces “platform tax” and makes it easier for a new licensee to win design slots—especially in mobile processors and embedded systems where time-to-market matters.

Tooling works best when the software stack is already there. Arm benefits from broad support across Linux, Android, and a wide range of RTOS options, plus common runtimes and libraries.

For many products, that turns chip bring-up from a research project into a repeatable engineering task.

When compilers are stable, debuggers are familiar, and OS ports are proven, licensees iterate faster: earlier prototypes, fewer integration surprises, and quicker releases.

In practice, that speed is a major part of why the Arm licensing model scales—CPU IP is the foundation, but tools and software toolchains make it usable at scale.

Arm’s model doesn’t mean every chip looks the same. It means partners start from a CPU foundation that already “fits” the existing software world, then compete in how they build everything around it.

Many products use a broadly compatible Arm CPU core (or CPU cluster) as the general-purpose engine, then add specialized blocks that define the product:

The result is a chip that runs familiar operating systems, compilers, and middleware, while still standing out on performance-per-watt, features, or bill of materials.

Even when two vendors license similar CPU IP, they can diverge through system-on-chip (SoC) integration: memory controllers, cache sizes, power management, camera/ISP blocks, audio DSPs, and the way everything is connected on-die.

These choices affect real-world behavior—battery life, latency, thermals, and cost—often more than a small CPU speed difference.

For phone makers, appliance brands, and industrial OEMs, a shared Arm software baseline reduces lock-in. They can switch suppliers (or dual-source) while keeping much of the same OS, apps, drivers, and development tools—avoiding a “rewrite the product” scenario when supply, pricing, or performance needs change.

Partners also differentiate by shipping reference designs, validated software stacks, and proven board designs. That reduces risk for OEMs, speeds regulatory and reliability work, and compresses time-to-market—sometimes becoming the deciding factor over a slightly faster benchmark score.

Arm scales by shipping design blueprints (CPU IP), while foundries scale by shipping physical capacity (wafers). Both enable lots of chips, but they compound value in different ways.

A modern chip typically passes through four distinct players:

Arm’s scale is horizontal: one CPU foundation can serve many chip designers, across many product categories.

Because Arm doesn’t manufacture, its partners aren’t locked into a single manufacturing strategy. A chip designer can choose a foundry and process that fits the job—balancing cost, power, availability, packaging options, and timing—without needing the IP provider to “retool” a factory.

That separation also encourages experimentation. Partners can target different price points or markets while still building on a shared CPU base.

Foundry scale is constrained by physical build-out and long planning cycles. If demand shifts, adding capacity isn’t instant.

IP scale is different: once a CPU design is available, many partners can implement it and manufacture where it makes sense. Designers may be able to shift production between foundries (depending on design choices and agreements) rather than being tied to a single owned-fab roadmap. That flexibility can help manage supply risk—even when manufacturing conditions change.

Arm mostly makes money in two ways: upfront license fees and ongoing royalties.

A company pays Arm for the right to use Arm’s CPU designs (or parts of them) in a chip. This fee helps cover the work Arm already did—designing the CPU core, validating it, documenting it, and making it usable by many different chip teams.

Think of it like paying for a proven engine design before you start building cars.

Once chips go into real products—phones, routers, sensors, appliances—Arm can receive a small fee per chip (or per device, depending on the agreement). This is where the model scales: if a partner’s product becomes popular, Arm benefits too.

Royalties also align incentives in a practical way:

Royalties reward broad adoption, not just a single big deal. That pushes Arm to invest in the unglamorous things that make adoption easier—compatibility, reference designs, and long-lived support.

If customers know that software and tools will keep working across multiple chip generations, they can plan product roadmaps with less risk. That predictability reduces porting costs, shortens testing cycles, and makes it easier to support products for years—especially in embedded systems.

A simple flow diagram could show:

Arm → (license) → Chip designer → (chips) → Device maker → (devices sold) → Royalties flow back to Arm

A licensing-led ecosystem can scale faster than a single company building every chip itself—but it also means giving up some control. When your technology becomes a foundation used by many partners, your success depends on their execution, their product decisions, and how consistently the overall platform behaves in the real world.

Arm doesn’t ship the final phone or the final microcontroller. Partners choose process nodes, cache sizes, memory controllers, security features, and power-management schemes. That freedom is the point—but it can make quality and user experience uneven.

If a device feels slow, overheats, or has poor battery life, users rarely blame a specific “core.” They blame the product. Over time, inconsistent outcomes can dilute the perceived value of the underlying IP.

The more partners customize, the more the ecosystem risks drifting into “same-but-different” implementations. Most software portability still holds, but developers can run into edge cases:

Fragmentation often shows up not at the instruction-set level but in drivers, firmware behavior, and platform features around the CPU.

An ecosystem model competes on two fronts: alternative architectures and partners’ in-house designs. If a large customer decides to build its own CPU core, the licensing business can lose volume quickly. Likewise, credible competitors can attract new projects by offering simpler pricing, tighter integration, or a faster path to differentiation.

Partners bet years of planning on a stable platform. Clear roadmaps, predictable licensing terms, and consistent compatibility rules are essential. Trust also depends on good stewardship: partners want confidence that the platform owner won’t unexpectedly change direction, restrict access, or undermine their ability to differentiate.

Arm’s story is a reminder that scale doesn’t always mean “own more factories.” It can mean making it easy for many others to build compatible products that still compete in their own way.

First, standardize the layer that creates the most reuse. For Arm, that’s the CPU instruction set and core IP—stable enough to attract software and tools, but evolving in controlled steps.

Second, make adoption cheaper than switching. Clear terms, predictable roadmaps, and strong documentation reduce friction for new partners.

Third, invest early in the “boring” enablers: compilers, debuggers, reference designs, and validation programs. These are the hidden multipliers that turn a technical spec into a usable platform.

Fourth, let partners differentiate above the shared foundation. When the base is compatible, competition moves to integration, power efficiency, security features, packaging, and price—where many companies can win.

A useful software analogy: Koder.ai applies a similar platform lesson to application development. By standardizing the “foundation layer” (a chat-driven workflow backed by LLMs and an agent architecture) while still allowing teams to export source code, deploy/host, use custom domains, and roll back via snapshots, it reduces the platform tax of shipping web/mobile/backend apps—much like Arm reduces the platform tax of building chips on a shared ISA.

Licensing and ecosystem-building is often the better bet when:

Vertical integration is often stronger when you need tight control over supply, yield, or a tightly-coupled hardware/software experience.

If you’re thinking about platform strategy—APIs, SDKs, partner programs, or pricing models—browse more examples in /blog.

Compatibility is powerful, but it’s not automatic. It has to be earned through consistent decisions, careful versioning, and ongoing support—otherwise the ecosystem fragments and the advantage disappears.

Arm usually licenses CPU intellectual property (IP)—either the instruction set architecture (ISA), a ready-to-integrate CPU core design, or both. The license gives you legal rights plus technical deliverables (like RTL and documentation) so you can build your own chip around it.

The ISA is the software/hardware contract: the instruction “language” machine code uses. A CPU core is one concrete implementation of that ISA (the microarchitecture). An SoC (system-on-chip) is the full product that includes CPU cores plus GPU, memory controllers, I/O, radios, security blocks, and more.

A core license lets you integrate an Arm-designed CPU core into your SoC. You’re mostly doing integration, verification, and system-level design around a proven CPU block.

An architecture license lets you design your own CPU core that implements the Arm ISA, so it stays Arm-compatible while giving you more control over microarchitecture decisions.

Common deliverables include:

Because CPU IP is reusable: once a core design is validated, many partners can integrate it in parallel across different products. That reuse lowers risk (fewer late surprises), speeds schedules, and lets each partner focus effort on what’s unique—like power management, cache sizing, or custom accelerators.

Manufacturing advantages help with unit cost and sometimes performance, but they’re expensive, cyclical, and hard to apply across every niche.

Ecosystem compatibility reduces total product cost (engineering time, porting, tooling, maintenance) because software, skills, and third-party components transfer across devices. Over multiple generations, that “rewrite tax” often dominates.

Mobile devices are power- and thermal-limited: sustained performance matters more than short peak bursts. Arm’s model also enabled competition without software chaos—multiple vendors could ship different chips (GPU/modem/NPU choices, integration strategies) while keeping a compatible CPU/software baseline.

Embedded products often have long lifecycles (years) and need stable maintenance, security patching, and supply continuity.

A consistent CPU/software foundation helps teams:

That’s valuable when you’re supporting devices long after launch.

Mature tooling reduces the “platform tax.” For Arm targets, teams can usually rely on established compilers (GCC/Clang), debuggers (GDB/IDE integrations), profilers, and OS support (Linux/Android/RTOS). That means faster bring-up, fewer custom toolchain surprises, and quicker iteration even before final silicon arrives.

Typically with two revenue streams:

If you want a focused breakdown, see /blog/the-licensing-economics-plain-english-version.

You typically don’t get a manufactured chip—manufacturing is handled by the licensee and their foundry.