May 15, 2025·8 min

Autodesk File Formats: Why CAD Lock-In Runs So Deep

Autodesk formats like DWG and RVT can shape tools, teams, and vendors. Learn how lock-in forms across AEC and manufacturing—and how to reduce it.

Autodesk formats like DWG and RVT can shape tools, teams, and vendors. Learn how lock-in forms across AEC and manufacturing—and how to reduce it.

“Lock-in” in CAD isn’t just “I like this software.” It’s the situation where switching tools creates real friction and real cost because your work depends on a whole stack of connected choices.

In design teams, lock-in usually shows up across four areas:

Features influence day-to-day productivity. File formats determine whether your work remains usable over years, across projects, and between companies. If a format is the default in your market, it becomes a shared language—often more important than any single button in the UI.

That’s why lock-in can persist even when alternatives exist: it’s hard to beat a format that everyone around you already expects.

We’ll look at the specific mechanisms that create lock-in across AEC (where BIM models can become the workflow itself) and manufacturing (where “geometry” is only part of the deliverable—tolerances, drawings, and downstream processes matter).

This is a practical breakdown of how lock-in happens—not product rumors, licensing speculation, or policy debates.

Teams rarely choose “a file format.” They choose a tool—and then the format quietly becomes the project’s memory.

A CAD or BIM file isn’t just geometry. Over time it accumulates decisions: layers, naming conventions, constraints, views, schedules, annotations, revision history, and the assumptions behind them. Once a project depends on that file to answer everyday questions (“Which option is current?” “What changed since last issue?”), the format becomes the single source of truth.

At that point, switching software isn’t mainly about learning new buttons. It’s about preserving the meaning embedded in the file so the next person can open it and understand it without rebuilding context.

The “default exchange format” in an industry acts like a common language. If most consultants, clients, reviewers, and fabricators expect a particular file type, every new participant benefits from already speaking it. That creates a network effect: the more widely a format is used, the more valuable it becomes, and the harder it is to avoid.

Even if an alternative tool is faster or cheaper, it can feel risky if it requires constant exporting, re-checking, and explaining “why this file looks different.”

Much of real productivity comes from repeatable assets:

These are format-native investments. They make teams consistent—and they anchor teams to the format that stores them best.

Most lock-in isn’t a deliberate commitment. It’s the byproduct of doing sensible things: standardizing deliverables, reusing proven components, and collaborating with partners. File formats turn those good habits into long-term dependencies.

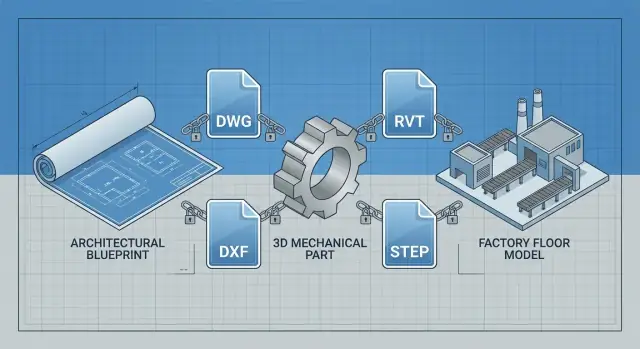

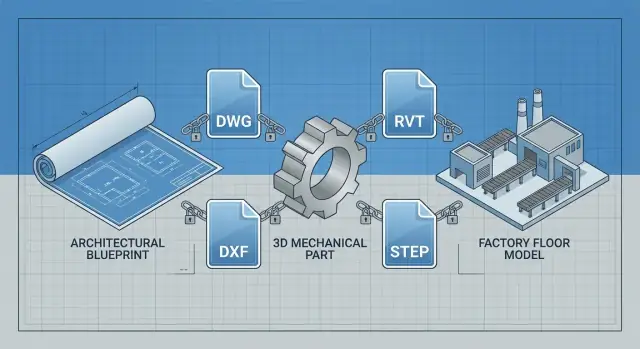

DWG and DXF sit at the center of day-to-day CAD exchange. Even teams that use different tools often converge on these formats when they need to share a base plan, a set of details, or a reference model. That shared “default” creates a kind of pull: once a project’s deliverables and downstream partners expect DWG/DXF, switching authoring tools becomes less about preference and more about meeting the file requirement.

Many CAD apps can open a DWG or import a DXF. The harder part is getting a file that is fully editable with design intent preserved. “Intent” is the structure that makes the drawing efficient to modify—how objects were created, organized, constrained, and annotated.

A quick visual check can be misleading: the geometry may look right, yet the file may behave differently when someone tries to revise it under deadline.

When DWG/DXF moves between tools (or even between versions), common pain points include:

“DWG compatible” can mean very different things depending on the tool, the DWG version (and what features were used), and project rules like client CAD standards, plotting requirements, or consultant workflows. In practice, teams don’t just need files that open—they need files that survive reviews, redlines, and late-stage changes without introducing rework.

BIM isn’t just “3D.” In Revit, the model is a database of building objects—walls, doors, ducts, families—each with parameters, relationships, and rules. From that data, teams generate schedules, tags, quantities, sheets, views, filters, and phasing. When those deliverables are contract-critical, the RVT file stops being a drawing container and becomes the workflow itself.

Many AEC teams work from shared models, central files, and standardized libraries. Office templates define naming, view setups, sheets, annotation styles, keynotes, and parameters. Shared parameters and families encode “how we design here,” and projects depend on them for consistent documentation and coordination.

Once consultants and subcontractors align to those conventions, switching tools isn’t a simple export—it means re-creating standards and retraining habits across the entire project network.

Revit can export to formats like IFC, DWG, or SAT, but these often lose the “intelligence” that makes BIM valuable. A door may become generic geometry; MEP systems may lose connectivity; parameters may not map cleanly; schedules and view logic don’t travel.

Even when geometry transfers, the receiving tool may not understand Revit-specific families, constraints, or type/instance behavior. The result is usable visuals with weaker editability—“dumb geometry” that’s hard to update reliably.

Coordination workflows also depend on model structure: clash detection, linked models, model-based takeoffs, and issue tracking tied to element IDs and categories. When those identifiers and relationships don’t survive a handoff, teams fall back to manual coordination, screenshots, and rework—exactly the friction that keeps RVT at the center of many BIM projects.

The strongest lock-in often isn’t the file format itself—it’s the internal “operating system” a firm builds around it. Over time, CAD and BIM tools accumulate company-specific standards that make work faster, safer, and more consistent. Recreating that system in a new tool can take longer than migrating the projects.

Most teams have a set of expectations embedded in templates and libraries:

These aren’t just “nice to have.” They encode lessons learned from past projects: what caused RFIs, what failed in coordination, what clients routinely request.

A mature library saves hours on every sheet and reduces mistakes. The catch is that it’s tightly coupled to the behavior of DWG blocks, Revit families, view templates, shared parameters, and plotting/export settings.

Migrating isn’t only converting geometry—it’s rebuilding:

Larger firms depend on cross-office consistency: a project can move between studios, or surge staff can jump in without “learning the drawing.” QA teams enforce standards because it’s cheaper than catching errors in construction.

Sometimes the standard isn’t optional. Public-sector clients and regulatory submissions may mandate specific outputs (for example, particular DWG conventions, PDF sheet sets, COBie fields, or model deliverables tied to RVT-based workflows). If your compliance checklist assumes those outputs, the tool choice becomes constrained—even before the first line is drawn.

Collaboration is where software preference hardens into a rule. A single designer can work around format friction. A multi-party project can’t—because every handoff adds cost, delay, and liability when data isn’t “native enough.”

A typical project data chain looks like:

Design → internal review → client review → multidisciplinary coordination → estimating/quantity takeoff → procurement → fabrication/detailing → installation → as-built/record model.

Each step involves different tools, different tolerances for ambiguity, and different risks if something is misread.

Every handoff is a question: “Can I trust this file without rework?” Native formats usually win because they preserve intent, not just geometry.

A coordinator may need levels, grids, and parametric relationships—not just exported shapes. An estimator may rely on consistent object classification and properties to avoid manual measurement. A fabricator may need clean, editable curves, layers, or families to generate shop drawings without rebuilding.

When exports lose metadata, change history, constraints, or object intelligence, the receiving party often responds with a simple policy: “Send the native file.” That policy reduces risk for them—and shifts the burden back upstream.

It’s not only your team’s choice. External parties often set the bar:

Once a major stakeholder standardizes on a format (for example DWG for drafting or RVT for BIM workflows), the project quietly becomes “a DWG job” or “a Revit job.” Even if alternatives are technically capable, the cost of convincing every partner—and policing every export/import edge case—usually outweighs the license savings.

The tool becomes a project requirement because the format becomes the coordination contract.

File compatibility is only one piece of the puzzle. Many teams stay on Autodesk tools because the surrounding ecosystem quietly holds the workflow together—especially once projects span multiple firms and specialized steps.

A typical Autodesk-centered stack touches more than “design.” It often includes rendering tools, simulation and analysis, cost estimating/quantity takeoff, document control, issue tracking, and project management systems. Add plotting standards, title blocks, sheet sets, and publish pipelines, and you get a chain where each link assumes certain Autodesk data structures.

Even when another CAD tool can import DWG or a BIM tool can open an exported model, the surrounding systems may not understand it the same way. The result is not a hard failure so much as slow leaks: lost metadata, inconsistent parameters, broken sheet automation, and manual rework that wasn’t budgeted.

Plugins and APIs deepen dependence because they encode business rules into one platform: custom room/space validation, automated tagging, standards checking, export-to-estimating buttons, or direct publishing to a document control system.

Once those add-ins become “how work gets done,” the platform stops being a tool and becomes infrastructure. Replacing it means re-buying plugins, re-certifying integrations with external partners, or rebuilding internal tools.

Many teams have scripts, Dynamo/AutoLISP routines, and custom add-ins that eliminate repetitive work. That’s a competitive advantage—until you switch.

Even if files can be imported, automations often can’t. You may open the model, but lose the repeatable process around it. That’s why switching costs show up as schedule risk, not just software spend.

A similar dynamic shows up outside CAD too: when you build internal web tools around one vendor’s assumptions, you can accidentally recreate lock-in. Platforms like Koder.ai (a chat-driven app-building platform with planning mode, snapshots/rollback, and source-code export) can help teams prototype and ship internal workflow tools while keeping an “exit path” via exported code—so your process doesn’t become inseparable from a single interface.

File formats get most of the attention, but people create the stickiest kind of lock-in. After a few years in AutoCAD or Revit, productivity isn’t just “knowing the buttons”—it’s built from habits, shortcuts, and conventions that live in muscle memory.

Teams move fast because they share unwritten practices: layer naming instincts, typical view setups, preferred annotation styles, and the shortcuts that keep drafting or modeling flowing. Switching tools means paying twice—once to learn the new interface, and again to rebuild the team’s shared way of working.

In AEC and engineering, job postings often specify “Revit required” or “AutoCAD proficiency.” Candidates self-select based on those expectations, universities teach to them, and recruiters filter for them. Certifications and portfolio norms (e.g., “send an RVT with worksets intact” or “deliver DWGs with our layer standards”) reinforce a market where the incumbent tool is treated as a baseline skill.

Even when leadership wants alternatives, onboarding materials, internal SOPs, and mentor time usually assume the current Autodesk workflow. New hires become productive by copying existing projects and templates—so every training session quietly deepens dependency.

The biggest cost is often the short-term productivity drop:

That temporary hit can be unacceptable during active projects, which makes “we’ll switch later” the default—and later rarely arrives.

Manufacturing teams don’t just need a shape—they need a definition of the part and a way to control change. That definition often includes parametric features, assemblies, tolerances, toolpaths, and a traceable revision history.

When your supplier (or your own shop) expects that full package in a specific CAD ecosystem, switching tools becomes less about preference and more about avoiding production risk.

A “good” handoff can mean different things depending on the workflow:

Neutral formats like STEP and IGES are great at moving geometry between systems—but they typically don’t transfer the full design intent: feature history, constraints, parametric relationships, and many CAD-specific metadata fields. You can open a STEP file and see the part, but you may not be able to edit it the way it was designed.

When intent is lost, teams re-create features, re-apply constraints, and re-validate drawings. That introduces risks: incorrect hole callouts, broken fits in assemblies, missing draft angles, or tolerances that don’t match the original assumptions.

Even if geometry looks right, the time spent confirming “right enough” adds hidden cost.

Suppliers often request native CAD files (or return markups in them) because that’s how they quote, program CNC, and manage revisions. If your partners standardize on a specific file type, your “interoperability” requirement quietly becomes a procurement requirement—especially when rework, delays, or scrap are on the line.

Lock-in costs rarely appear as a single line item. They show up as small frictions—extra hours fixing imports, “temporary” parallel licenses, or a schedule buffer that quietly becomes permanent. A quick checklist helps you surface them early and put numbers next to them.

Treat translation as partial compatibility, not a yes/no.

Total switching cost ≈ Licenses (overlap period) + Training (courses + slowed output) + Rework (translation fixes + rebuilds) + Schedule impact (delays × project burn rate).

Write down assumptions (rates, overlap months, file samples) and validate them with a short pilot. Testing with real project files is the fastest way to replace opinions with evidence.

Reducing CAD lock-in doesn’t have to mean “rip and replace.” The goal is to preserve delivery certainty while making future switching (or multi-tool work) less painful.

Keep legacy projects on the system they were started in, especially if they rely on established libraries, past detail sheets, or client handover requirements.

In parallel, pilot new projects (or a well-defined package within a project) using an alternative tool. Pick pilots that are low-risk but real: a small building, a single discipline, or a repeatable component family.

This avoids disrupting active deadlines while building confidence, reference examples, and internal champions.

Neutral formats can reduce dependency on a single vendor:

Be explicit about what each format is “good enough” for, and what must stay native.

Lock-in often hides in messy structure. Adopt naming standards, consistent metadata (project, discipline, status), clear versioning rules, and an archiving strategy that captures “final issued” alongside key transmittals and references.

Customization speeds work—until you need to export. Minimize features that can’t travel: overly complex object enablers, brittle macros, or templates tied to one add-in.

When you do customize, document it and keep a simpler fallback template that still meets standards.

Done gradually, these steps keep delivery stable while increasing data portability year by year.

Switching CAD/BIM tools isn’t a “yes/no” decision—it’s a risk-managed sequence of tests. A good framework separates what you must keep editable from what only needs to be deliverable.

Stay if most revenue depends on native DWG/RVT deliverables, long-lived editable archives, or tight partner ecosystems you can’t influence.

Switch (or diversify) when license costs are secondary to productivity gains, your deliverables are largely export-based, or you can standardize on open exchanges (IFC/STEP) and reduce “native-only” dependencies over time.

CAD/BIM lock-in is when switching tools creates real cost and risk because your work depends on a whole stack: native files, libraries, templates, standards, integrations, and partner expectations—not just personal preference.

A practical test: if moving off a tool would force you to rebuild intent (constraints, families, metadata, schedules) or change deliverables your partners require, you’re dealing with lock-in.

Features affect speed today; formats affect whether work stays usable and editable over years.

If a format becomes the project’s “memory” (layers, constraints, views, revisions, parameters), switching tools risks losing meaning—even if the geometry looks fine. That’s why a widely expected format can outweigh a better UI or lower price.

Because the file often becomes the single source of truth: it accumulates decisions like naming conventions, constraints, view logic, schedules, annotations, and revision context.

When teams rely on the file to answer questions (“what changed?”, “which option is current?”), the format stops being a container and becomes the project’s operating record.

Network effects happen when a format becomes the default language in your industry. The more clients/consultants/fabricators who expect it, the less translation is needed, so the format becomes even more valuable.

Practically, this shows up as policies like “send native DWG/RVT” because it reduces review and rework risk for the receiver.

A file can open and still be painful to edit. The biggest gap is losing design intent:

A quick visual check can miss problems that appear during late-stage revisions under deadline.

Common losses include:

In Revit-style BIM, the model is a database of objects and relationships (families, parameters, connectivity, view/schedule logic). Contract-critical outputs—sheets, tags, schedules, quantities—are generated from that data.

So the RVT isn’t just a file format; it’s the workflow. Exports may carry geometry, but often lose the behaviors teams rely on to coordinate and document changes.

They usually produce a downgrade in editability:

Exports like IFC/DWG/SAT can be great for coordination or deliverables, but they rarely replace native BIM for ongoing iteration and change management.

They’re format-native investments that encode “how we work”:

Recreating this internal system is often more expensive than converting a few projects, which is why mature standards and libraries anchor teams to a platform.

Do a small, evidence-based pilot and quantify friction:

avg fix time × file count × frequency.Then decide what stays native vs what can be delivered as PDF/IFC/STEP without downstream rework.

To manage this, test with representative files and verify print/output, not just on-screen geometry.