Oct 18, 2025·8 min

Baidu’s Search, Maps, and AI Bet: Winning via Distribution

Explore how Baidu balances search, maps, and AI spending while defaults, apps, and partnerships shape user access—and product power in China.

Explore how Baidu balances search, maps, and AI spending while defaults, apps, and partnerships shape user access—and product power in China.

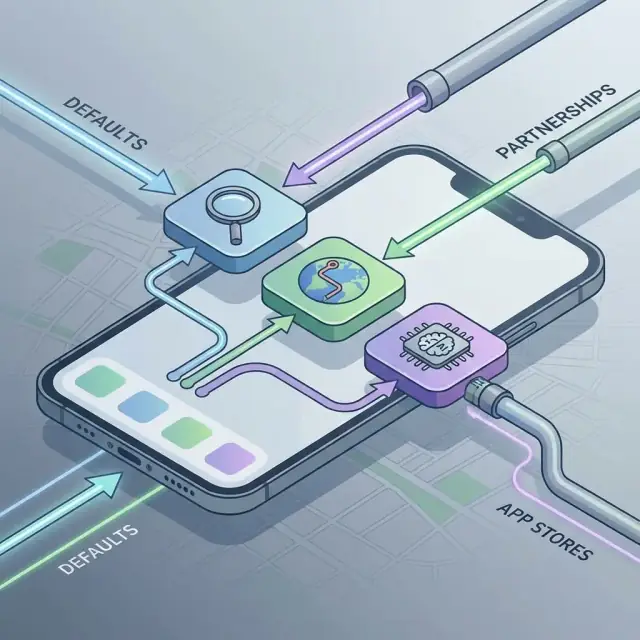

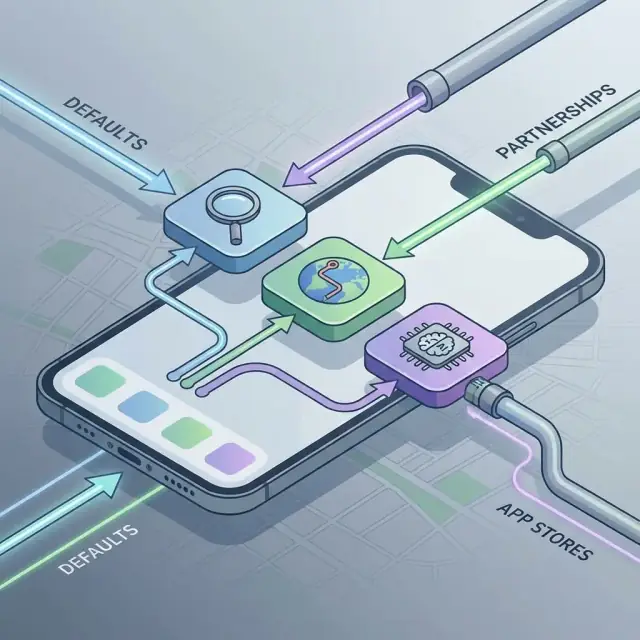

“Distribution” in consumer internet products is the set of channels that put a product in front of people at the moment of need. That includes being the default option (the search box a phone ships with), prime placement (a widget, a home-screen slot, a top tab), and traffic sources (links from other apps, OEM partnerships, browser toolbars, notification surfaces, or preloaded shortcuts).

Many products are “good enough.” When that’s true, the winner is often the one users reach with the fewest taps and the least friction. Defaults and preinstalls create habit loops: people don’t re-evaluate every time they want directions or an answer—they use what’s already there. And once a service has steady access, it can learn faster, monetize more reliably, and reinvest to improve.

This doesn’t mean features don’t matter. It means features and distribution trade off: a superior product can struggle if it’s buried; a merely solid product can thrive if it’s the easiest path.

Baidu is easiest to understand as a set of “surfaces” that capture intent:

Each surface has its own user moments—but their outcomes are heavily shaped by how users arrive there.

So the core lens for this article is distribution-first: who controls access, and what does that control enable? If competitors win attention inside superapps, if phone makers steer defaults, or if users start in maps instead of search, Baidu’s product power changes—even before we compare features.

Baidu Search is still a default mental model for many users when the job is to “look something up” and get a result that feels authoritative enough to act on. That includes straightforward information (definitions, news context, comparisons), but also service-oriented queries—finding a clinic, checking a brand’s official site, troubleshooting a phone issue, or confirming a policy requirement.

A useful way to frame Baidu’s current strength is that it sits at the intersection of intent and verification. Users often turn to it when they want a quick answer, and also when they want to validate what they saw elsewhere.

Common patterns include:

Being the first stop matters because it captures intent before it turns into a decision. If a user begins with a query like “best orthodontist near me” or “which phone has the best battery,” the search engine can shape the shortlist, route traffic to merchants, and influence which options feel “trusted.” That’s why intent-based queries remain commercially powerful: they’re closer to outcomes (calls, bookings, visits, purchases) than general browsing.

Users increasingly start inside apps, not in a browser. Product discovery can begin on superapps, short-video feeds, ecommerce platforms, or local service apps that already know your location, preferences, and payment method. Those environments can answer the question and complete the transaction without sending you back to open web search.

So Baidu’s win condition in search is narrower but still meaningful: be the fastest, most reliable “decision checkpoint” for high-intent queries—and then hand off smoothly to maps, calls, bookings, and other actions that turn attention into measurable results.

Baidu Maps behaves less like a “feature” and more like a daily utility. People open it for the same reason they check weather or messages: it reduces uncertainty in the next hour. Commutes, pickups, delivery timing, avoiding congestion, meeting points—each use is small, but the frequency is high. That repetition matters because it creates a habit loop that search alone can’t always sustain.

The moment someone asks for directions, they’re implicitly declaring local intent: I’m going somewhere, soon. That makes maps a natural on-ramp to nearby decisions—where to eat, which store is actually open, what service is available within a reasonable detour, or which route gets you there with the least friction.

Navigation sessions are full of “micro-moments” where suggestions can help without feeling like ads: a quick stop for coffee, the closest pharmacy, parking options, or a faster route if traffic spikes. For travel and unfamiliar neighborhoods, the map becomes the interface for choosing hotels, attractions, transit options, and even the best time to leave.

Place listings are effectively a structured local database: address, hours, photos, menus, pricing cues, and category tags. Add reviews and popularity signals, and maps becomes a discovery engine—one that answers questions people might not phrase as queries.

Instead of typing “best noodles near me,” a user can scan the map, filter by cuisine, and compare options by distance, rating, and foot traffic. This shifts discovery from searching for information to browsing for a decision, which is often faster and feels more grounded because it’s tied to location and time.

Because maps sits at the moment of intent, it can route users into other Baidu experiences with minimal extra effort:

In a market where access points matter, Baidu Maps is powerful precisely because it’s opened often, used quickly, and anchored to real-world intent—making it a high-frequency gateway into the rest of Baidu’s local and search ecosystem.

Baidu’s AI story is often told in terms of budget and breakthroughs. But in markets where distribution determines what people actually use, the practical question is: how does that AI show up in everyday behavior?

AI spend isn’t one line item. It can include:

The headline model matters—but the “boring” layers (deployment, latency, reliability, compliance) often decide whether the model becomes a product.

There are two distinct ways AI can create value.

AI as a feature layer enhances existing products: better query understanding in Baidu Search, smarter routing and place recommendations in Baidu Maps, improved ad targeting, richer summaries, and faster task completion.

AI as a new distribution surface is different: standalone assistants, chat-style entry points, or system-level experiences that become the starting place for tasks. If that surface is where users begin, it can redirect attention away from classic search boxes and app icons.

The highest leverage for Baidu is getting AI into workflows people already repeat: “find a restaurant,” “navigate there,” “what’s nearby,” “compare options,” “book,” “pay,” “review.” That means embedding AI into search and maps flows, not treating it as a separate demo.

The catch is simple: spending alone doesn’t guarantee adoption. Without access—defaults, preinstalls, strong placements, and tight integrations—AI products can remain impressive, underused features instead of habit-forming destinations.

A surprising amount of “market share” isn’t won by persuading users—it’s won by being the first thing they see.

When a search box is already on the home screen, or a map app is already the default handler for addresses, many people never make an explicit choice. They simply use what’s there. That behavior is rational: it’s faster, it feels “official,” and it works well enough for the everyday job.

In China’s mobile ecosystem, access is often negotiated rather than earned one click at a time. The most common distribution channels include:

Each of these channels compresses the “cost” of trying the product to near zero.

Even if competing products offer similar features, defaults compound over time because users accumulate small, personal investments:

These aren’t dramatic lock-ins. They’re everyday frictions that add up.

Distribution agreements can reshape competition more than incremental product improvements. If Baidu secures default placement or privileged entry points, it can capture the highest-intent moments (typing a query, tapping a location) before rivals even get a chance to compete. In that sense, “product power” is partly a function of access economics—who pays (or partners) to sit closest to user intent.

Superapps change what “search” means. Instead of typing a query into a browser or a dedicated search app, people often search within the app they already have open—looking up a restaurant inside a food-delivery app, a product inside an e-commerce app, or a nearby service inside a payments app. The query still exists, but the “starting point” (and the winner) is the app that owns the session.

Mini programs and in-app services push this further. They let users complete tasks—bookings, purchases, customer service, loyalty programs—without leaving the host app. That creates alternative entry points to information and transactions that used to flow through open web pages.

For Baidu, this matters because many high-value intents (local, shopping, services) can be satisfied before a user ever reaches a traditional search results page. Even when a user is “searching,” the discovery happens inside a closed ecosystem with its own rankings, ads, and merchant integrations.

As attention concentrates in superapps, fewer journeys include an open-web search step. More journeys become closed loops: browse → decide → transact, all inside one platform. That compresses the opportunity for Baidu to capture demand at the moment of intent—and it can reduce the data feedback Baidu gets from clicks and conversions.

To stay relevant, Baidu has to earn distribution inside these ecosystems: integrations that answer queries where they happen, partnerships that bring Baidu’s results into in-app search boxes, and differentiated capabilities (especially local intent, trusted answers, and AI features) that platforms or mini programs can’t easily replicate.

The goal isn’t only to pull users back to Baidu—it’s to be present at the real starting points.

Baidu’s monetization works best when it attaches ads to clear intent—moments when a user is trying to do something, not just browse. Search and maps both generate these high-signal moments, which makes it easier to sell outcomes rather than impressions.

Search advertising is still the cleanest pathway from query to action. A keyword like “dentist near me,” “moving company price,” or “best hotpot in Chaoyang” is inherently measurable: it can be tied to clicks, calls, form fills, and even downstream appointments. That measurability supports performance-style budgeting, where advertisers keep spending as long as cost-per-lead or cost-per-acquisition stays within target.

Maps create monetization paths that feel closer to “foot traffic” than “media.” Common models include:

Because map interactions occur near the moment of purchase, advertisers often accept higher prices—if they trust the tracking.

Aggressive monetization (too many ads, unclear labeling, low-quality lead sources) can degrade the product quickly: users stop trusting results, and good merchants stop bidding when leads don’t convert. The long-term winner is the platform that keeps ad load disciplined and enforces merchant quality.

Baidu’s ability to attribute outcomes—call tracking, coupon redemption, navigation-to-visit signals, and conversion reporting—determines whether local businesses treat it as a core channel or an experimental one. When reporting matches real-world results, spend becomes recurring; when it doesn’t, the budget migrates to substitutes inside superapps and vertical platforms.

A “data flywheel” is a simple loop: users do something → you collect data → the product gets better → more users do more things. If the loop keeps spinning, improvement becomes compounding rather than incremental.

Baidu Search captures what people want, while Baidu Maps captures where and when they want it. Put together, those signals are unusually powerful for intent.

When someone searches “hot pot near me,” clicks a result, opens directions in Baidu Maps, and later leaves a review, Baidu gets multiple clues:

AI personalization can then use those patterns to rank results more usefully: not just “popular restaurants,” but “places like this that people with similar intent actually visit.” Over time, that can improve everything from local search relevance to estimated wait times, suggested routes, and which listings deserve richer cards.

Flywheels don’t spin on “more data” alone—they spin on good data. Local products are especially exposed to:

If users repeatedly arrive at closed shops or scammy services, they stop clicking—and the loop reverses.

Trust is the prerequisite for feedback. Users only contribute high-quality signals (clicks, visits, reviews) when they believe results are accurate. Relevance is the prerequisite for usage: if Search and Maps don’t reliably answer local questions, users shift those queries into superapps, cutting Baidu off from the very data it needs to improve.

Baidu doesn’t only compete with “other search engines.” It competes with every product that captures the moment before a user forms a query. In China, that moment is often inside an app—so the real battle is for the starting point.

A growing share of discovery happens through:

These behaviors are substitutes because they satisfy intent upstream. By the time the user needs directions or a price, the decision is partly made.

Not all “search” is the same. Players tend to dominate by intent:

That means Baidu can be strong in classic information retrieval while still losing high-value local and lifestyle intent if users begin elsewhere.

Winning mindshare is hard; winning distribution can be bought or negotiated. OEM channels, app stores, and default settings determine which icon is visible, which assistant answers first, and which app opens links.

For Baidu’s strategy, the key question is: where does the user start for each intent? If the starting point is a superapp feed, Baidu needs routes back in (cards, deep links, partnerships). If the starting point is the home screen, defaults and preinstalls become decisive.

Regulation in China doesn’t just sit “outside” the product—it changes what search, maps, and AI are allowed to show, how fast they can update, and what must be reviewed. Compliance is an ongoing product cost: building moderation tooling, auditing partners, handling takedown requests, and maintaining records that can stand up to scrutiny.

Search ranking and local listings need governance features baked in: verified business identities, clearer ad labels, and stricter onboarding for categories prone to abuse (healthcare, finance, education). Those controls reduce risk, but they also add friction—more steps for merchants, slower iteration for product teams, and higher operating expense.

For Baidu Maps in particular, listing accuracy is inseparable from compliance. If users repeatedly encounter fake addresses, bait-and-switch pricing, or spammy POIs, they stop trusting the map for high-intent decisions like where to eat or which clinic to visit.

Trust becomes a differentiator when results look similar across platforms. A search engine that consistently removes scams, labels promotions clearly, and surfaces reliable sources can win repeat usage—even if a competitor has flashier features.

User concerns are practical and persistent:

AI-generated responses raise the stakes. If an AI answer is wrong, biased, or promotional without disclosure, users feel misled. Governance affects:

In short: distribution gets users in the door, but regulation and trust determine whether they stay—and whether Baidu can safely expand AI into everyday decisions.

Baidu’s next leg of growth is less about inventing a brand-new behavior and more about placing helpful AI and local intent features exactly where Chinese users already start—on their phones, in cars, and inside high-frequency apps.

Distribution lever: system defaults and OEM preinstalls that set Baidu (and its AI mode) as the first-stop search box, plus prominent placement in the browser address bar.

Winning in user terms: fewer query refinements, faster summaries that cite sources, and safer results for sensitive topics (health, finance, travel) with clearer confidence signals.

Risks: users may shift habits toward superapps for “good enough” answers, or prefer vertical apps where the data is fresher (shopping, reviews, short video).

Distribution lever: deep integrations in Baidu Maps—ride-hailing, parking, fuel/charging, reservations—plus partnerships with property managers, malls, and city services that make Maps the default entry point.

Winning in user terms: fewer wrong turns and fewer wasted trips—accurate ETAs, reliable entrances, indoor guidance, and one-tap actions (book, pay, check-in).

Risks: closed ecosystems can limit access to merchant inventory, and inconsistent on-the-ground data quality can break trust quickly.

Distribution lever: embedded infotainment deals with automakers and Tier-1 suppliers, making Baidu the out-of-the-box voice assistant and navigation brain.

Winning in user terms: safer driving (less screen time), smoother routing, and proactive alerts (construction, weather, charging availability) that reduce stress.

Risks: automakers may push their own assistants, and regulatory or privacy constraints could limit personalization.

Distribution lever: bundled AI writing, research, and translation features in enterprise/education partnerships and government procurement.

Winning in user terms: time saved on drafting, fact-checking, and document workflows, with stronger citation and auditability.

Risks: procurement cycles are slow, and trust hinges on accuracy, data handling, and clear accountability when outputs are wrong.

When distribution is gated by defaults, preinstalls, and superapps, “better product” isn’t just features—it’s being reachable at the moment of intent. Baidu’s story across search, maps, and AI offers a practical way to reason about that reach.

Use this checklist to evaluate any channel (OEM preinstall, browser default, superapp entry point, mini program, QR flows):

Think “surface-first,” not “brand-first.”

A useful test: where does the user already have a habit, and can your surface reduce steps at that exact moment?

Look beyond downloads and total MAU. Track:

Partnerships are leverage, but protect the long-term bond: keep clear identity/account continuity, preserve deep-linking into your core experiences, and negotiate data and measurement rights. Treat partners as distribution accelerators—while building features (history, saves, personalization, service guarantees) that make users choose you even when you’re no longer the default.

If you’re analyzing Baidu through a distribution lens and then trying to apply the same thinking to your own product, the bottleneck is often execution: building lightweight landing pages, onboarding flows, partner-specific variants, and instrumentation quickly enough to test channels before they shift.

Platforms like Koder.ai can help teams move faster here by vibe-coding web apps (React), backends (Go + PostgreSQL), and even companion mobile experiences (Flutter) from a chat interface—useful for spinning up channel-specific funnels, internal dashboards for cohort/activation tracking, or “planning mode” specs that align growth and engineering. The point isn’t the tool; it’s shortening the cycle between a distribution hypothesis and a measurable experiment.

A distribution-first lens focuses on who controls access at the moment of need—defaults, preinstalls, prime placement, deep links, and partnerships.

It matters because when products are “good enough,” the winner is often the one that’s reachable with the fewest taps, which then compounds into more usage, better monetization, and faster improvement.

Because in many consumer workflows, users don’t re-evaluate tools each time—they follow the default path.

Defaults and preinstalls create habit loops that can outweigh incremental feature differences, especially for high-frequency tasks like looking up info or getting directions.

The post frames Baidu as three core “surfaces” that capture intent:

Understanding how users arrive at each surface is key to understanding competitive power.

Baidu Search tends to win when users want lookup + verification—a fast answer that feels reliable enough to act on.

Common use cases include definitions and context, troubleshooting, checking official sites, and service-oriented queries where trust and clarity matter.

Pressure comes from users starting inside apps that can both answer and complete the transaction—superapps, ecommerce, short-video feeds, and vertical services.

If discovery and purchase happen in a closed loop, traditional web search gets fewer chances to intercept intent.

Maps is a daily utility with built-in “local intent”: opening directions implies you’re going somewhere soon.

That creates frequent micro-moments—coffee stops, pharmacies, parking, “open now”—where the map can influence decisions without requiring a separate search step.

Place listings and reviews turn a map into a structured local database (hours, menus, photos, categories, popularity).

Instead of typing a query, users can browse the map, filter options, compare distance and ratings, and make a decision faster because it’s grounded in time and location.

AI can show up in two ways:

The key is distribution: even strong models can be underused if they aren’t embedded in the workflows people already repeat.

Key access channels include:

These reduce the “try cost” to near zero and make usage feel official and effortless.

Baidu’s monetization is strongest when it attaches ads to clear, measurable intent.

Long-term performance depends on measurement quality (attribution) and user trust (ad labeling, merchant quality, spam control).