Jun 04, 2025·8 min

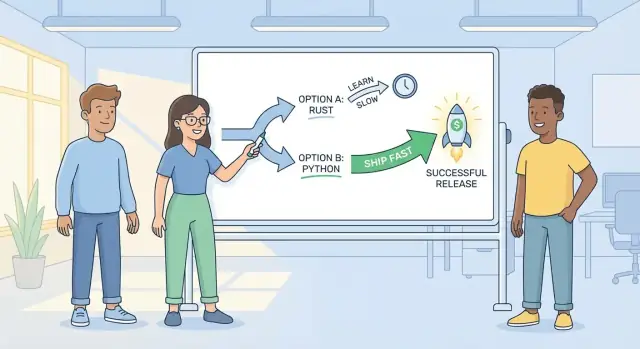

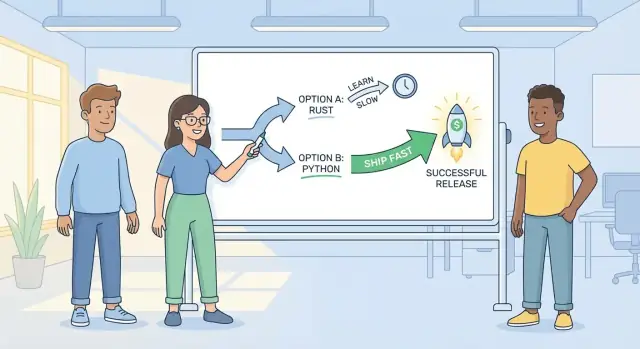

Why the Best Language Is the One Your Team Ships Fast

Choosing a programming language is rarely about “best on paper.” Learn a practical framework to pick what your team can deliver with quickly and safely.

Choosing a programming language is rarely about “best on paper.” Learn a practical framework to pick what your team can deliver with quickly and safely.

“Best language” debates usually stall because they’re framed like a universal ranking: which language is fastest, cleanest, most modern, or most loved. But teams don’t ship in a vacuum. They ship with specific people, specific deadlines, and a pile of existing systems that must keep working.

When your goal is to deliver customer value, “best” usually collapses into a more practical question: which option helps this team deliver safely and repeatedly with the least friction? A language that’s theoretically superior but slows delivery by weeks—because of unfamiliar tooling, missing libraries, or scarce hiring—won’t feel “best” for very long.

Constraints aren’t a compromise; they’re the real problem statement. Your team’s experience, current codebase, deployment setup, compliance needs, and integration points all shape what will ship fastest.

A few examples:

Shipping fast isn’t just writing code quickly. It’s the full cycle: picking up work, implementing it, testing it, deploying it, and monitoring it without anxiety.

A language supports “ship fast” when it improves cycle time and keeps quality stable—fewer regressions, simpler debugging, and reliable releases. The best language is the one that helps your team move quickly today while staying confident they can do it again next week.

Choosing a language isn’t an abstract “best tool” debate—it’s a bet on the people who will build, operate, and extend the product. Before comparing benchmarks or trendy stacks, take a clear-eyed snapshot of your team as it actually exists (not as you hope it will look in six months).

Start by listing what your team is already good at and where you routinely struggle.

Shipping “fast” includes keeping things running.

If your team carries an on-call rotation, factor that into the language choice. A stack that requires deep expertise to diagnose memory issues, concurrency bugs, or dependency conflicts can quietly tax the same few people every week.

Also include support responsibilities: customer-reported bugs, compliance requests, migrations, and internal tooling. If the language makes it hard to write reliable tests, build small scripts, or add telemetry, the speed you gain early often gets repaid with interest later.

A practical rule: pick the option that makes your median engineer effective, not just your strongest engineer impressive.

“Ship fast” sounds obvious until two people mean two different things: one means merge code quickly, another means deliver reliable value to customers. Before you compare languages, define what “fast” looks like for your team and your product.

Use a simple, shared scorecard that reflects the outcomes you care about:

A good metric is one you can collect with minimal debate. For example:

If you already track DORA metrics, use them. If not, start small with two or three numbers that match your goals.

Targets should reflect your context (team size, release cadence, compliance). Pair speed metrics with quality metrics so you don’t “ship fast” by shipping breakage.

Once you agree on the scoreboard, you can evaluate language options by asking: Which choice improves these numbers for our team in the next 3–6 months—and keeps them stable a year from now?

Before debating what language is “best,” take a clear inventory of what your team already owns—code, tooling, and constraints. This isn’t about clinging to the past; it’s about spotting hidden work that will slow delivery if you ignore it.

List the existing codebase and services your new work must integrate with. Pay attention to:

If most of your critical systems are already in one ecosystem (for example, JVM services, .NET services, or a Node backend), choosing a language that fits that ecosystem can remove months of glue code and operational headaches.

Your build, test, and deployment tooling is part of your effective “language.” A language that looks productive on paper can become slow if it doesn’t fit your CI, testing strategy, or release process.

Check what’s already in place:

If adopting a new language means rebuilding these from scratch, be honest about that cost.

Runtime environment constraints can narrow your options quickly: hosting limitations, edge execution, mobile requirements, or embedded hardware. Validate what’s allowed and supported (and by whom) before you get excited about a new stack.

A good inventory turns “language choice” into a practical decision: minimize new infrastructure, maximize reuse, and keep the path to shipping short.

Developer Experience (DX) is the daily friction (or lack of it) your team feels while building, testing, and shipping. Two languages can be equally “capable” on paper, but one will let you move faster because the tools, conventions, and ecosystem reduce decision fatigue.

Don’t ask “Is it easy to learn?” Ask “How long until our team can deliver production-quality work without constant review?”

A practical way to gauge this is to define a short onboarding target (for example, a new engineer can ship a small feature in week one, fix a bug in week two, and own a service by month two). Then compare languages by what your team already knows, how consistent the language is, and how opinionated the common frameworks are. “Flexible” can mean “endless choices,” which often slows teams down.

Speed depends on whether the boring parts are solved. Check for mature, well-supported options for:

Look for signs of maturity: stable releases, good docs, active maintainers, and a clear upgrade path. A popular package with messy breaking changes can cost more time than building a small piece yourself.

Shipping fast isn’t just writing code—it’s resolving surprises. Compare how easy it is to:

If diagnosing a slowdown requires deep expertise or custom tooling, your “fast” language may turn into slow incident recovery. Pick the option where your team can confidently answer: “What broke, why, and how do we fix it today?”

Speed to ship isn’t only about how quickly your current team can write code. It’s also about how quickly you can add capacity when priorities shift, someone leaves, or you need a specialist for a quarter.

Every language has a talent market, and that market has a real cost in time and money.

A practical test: ask your recruiter (or do a quick scan of job boards) how many candidates you can reasonably interview in two weeks for each stack.

Onboarding cost is often the hidden tax that slows delivery for months.

Track (or estimate) time-to-first-meaningful-PR: how long it takes a new developer to ship a safe, reviewed change that matters. Languages with familiar syntax, strong tooling, and common conventions tend to shorten this.

Also consider your documentation and local patterns: a “popular” language still onboards slowly if your codebase relies on niche frameworks or heavy internal abstractions.

Look beyond today’s team.

If you want a simple decision rule: prefer the language that minimizes time-to-hire + time-to-onboard, unless you have a clear performance or domain requirement that justifies the premium.

Shipping fast doesn’t mean gambling. It means setting up guardrails so ordinary days produce reliable outcomes—without relying on one senior engineer to “save the release” at midnight.

A stronger type system, strict compiler checks, or memory safety features can prevent whole classes of bugs. But the benefit only shows up if the team understands the rules and uses the tools consistently.

If adopting a safer language (or stricter mode) would slow day‑to‑day work because people fight the type checker, you may trade visible speed for hidden risk: workarounds, copy‑pasted patterns, and fragile code.

A practical middle path is to pick the language your team can work in confidently, then turn on the safety features you can sustain: strict null checks, conservative lint rules, or typed boundaries at APIs.

Most risk comes from inconsistency, not incompetence. Languages and ecosystems that encourage a default project structure (folders, naming, dependency layout, config conventions) make it easier to:

If the language’s ecosystem doesn’t provide strong conventions, you can still create your own template repo and enforce it with checks in CI.

Guardrails work when they’re automatic:

When choosing a language, look closely at how easy it is to set up these basics for a new repo. If “hello world” takes a day of build tooling and scripts, you’re setting the team up for heroics.

If you already have internal standards, document them once and link them from your engineering playbook (e.g., /blog/engineering-standards) so every new project starts protected.

Speed matters—but usually not the way engineering debates make it seem. The goal isn’t “the fastest language on a benchmark.” The goal is “fast enough” performance for the parts users actually feel, while keeping delivery speed high.

Start by naming the user-facing moments where performance is visible:

If you can’t point to a user story that improves with more performance, you probably don’t have a performance requirement—you have a preference.

Many products win by shipping improvements weekly, not by shaving milliseconds off endpoints that are already acceptable. A “fast enough” target might look like:

Once you’ve set targets, choose the language that helps you meet them reliably with your current team. Often, performance bottlenecks come from databases, network calls, third-party services, or inefficient queries—areas where language choice is secondary.

Picking a lower-level language “just in case” can backfire if it increases implementation time, reduces hiring options, or makes debugging harder. A practical pattern is:

That approach protects time to market while still leaving room for serious performance work when it’s truly needed.

Shipping fast today is only useful if your code can keep shipping fast next quarter—when new products, partners, and teams show up. When choosing a language, look beyond “Can we build it?” and ask “Can we keep integrating without slowing down?”

A language that supports clear boundaries makes it easier to scale delivery. This can be a modular monolith (well-defined packages/modules) or multiple services. What matters is whether teams can work in parallel without constant merge conflicts or shared “god” components.

Check for:

No stack stays pure. You may need to reuse an existing library, call into a platform SDK, or embed a high-performance component.

Practical questions:

Growth increases the number of callers. That’s when sloppy APIs turn into slowdowns.

Prefer languages and ecosystems that encourage:

If you standardize on a few integration patterns early—internal modules, service boundaries, and versioning rules—you protect shipping speed as the org scales.

Teams rarely disagree on goals (ship faster, fewer incidents, easier hiring). They disagree because trade-offs stay implicit. Before you pick a language—or justify sticking with one—write down what you’re intentionally optimizing for, and what you’re accepting as a cost.

Every language has “easy mode” and “hard mode.” Easy mode might be quick CRUD work, strong web frameworks, or great data tooling. Hard mode might be low-latency systems, mobile clients, or long-running background jobs.

Make this concrete by listing your top 3 product workloads (e.g., API + queue workers + reporting). For each workload, note:

“Shipping fast” includes everything after code is written. Languages differ a lot in operational friction:

A language that’s pleasant locally but painful in production can slow delivery more than a slower syntax ever will.

These costs sneak into every sprint:

If you make these trade-offs explicit, you can choose intentionally: maybe you accept slower builds for better hiring, or accept a smaller ecosystem for simpler deploys. The key is deciding as a team, not discovering by accident.

A language debate is easy to win on a whiteboard and hard to validate in production. The fastest way to cut through opinions is to run a short pilot where the only goal is to ship something real.

Choose one feature that looks like your normal work: touches a database, has a UI or API surface, needs tests, and must be deployed. Avoid “toy” examples that skip the boring parts.

Good pilot candidates include:

Keep it small enough to finish in days, not weeks. If it can’t ship quickly, it won’t teach you what “shipping” feels like.

Track time and friction across the whole workflow, not just coding.

Measure:

Write down surprises: missing libraries, confusing tooling, slow feedback loops, unclear error messages.

If you want to shorten the pilot loop even further, consider using a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai to prototype the same feature via chat, then export the source code for review. It can be a useful way to test “time to first working slice” (UI + API + database) while still keeping your normal engineering standards around tests, CI, and deployment.

At the end, do a short review: what shipped, how long it took, and what blocked progress. If possible, compare the pilot to a similar feature you shipped recently in your current stack.

Capture the decision in a lightweight doc: what you tested, the numbers you observed, and the trade-offs you’re accepting. That way the choice is traceable later—and easier to revisit if reality changes.

Choosing a language doesn’t have to feel permanent. Treat it like a business decision with an expiration date, not a lifelong commitment. The goal is to unlock shipping speed now while keeping your options open if reality changes.

Capture your decision criteria in a short doc: what you’re optimizing for, what you’re explicitly not optimizing for, and what would trigger a change. Include a revisit date (for example, 90 days after the first production release, then every 6–12 months).

Keep it concrete:

Reversibility is easier when your day-to-day work is consistent. Document conventions and bake them into templates so new code looks like existing code.

Create and maintain:

This reduces the number of hidden decisions developers make and makes later migration less chaotic.

You don’t need a full migration plan, but you do need a path.

Prefer boundaries that can be moved later: stable APIs between services, well-defined modules, and data access behind interfaces. Document what would make you migrate (e.g., performance requirements, vendor lock-in, hiring constraints) and the likely destination options. Even a one-page “if X happens, we do Y” plan will keep future debates focused and faster.

It’s the language and ecosystem that help your specific team deliver value safely and repeatedly with the least friction.

That usually means familiar tooling, predictable delivery, and fewer surprises across the whole cycle: build → test → deploy → monitor.

Because you don’t ship in a vacuum—you ship with existing people, systems, deadlines, and operational constraints.

A “better on paper” language can still lose if it adds weeks of onboarding, missing libraries, or operational complexity.

Shipping fast includes confidence, not just typing speed.

It’s the full loop: picking up work, implementing, testing, deploying, and monitoring with low anxiety and low rollback risk.

Start with a realistic snapshot:

Use a simple scorecard across speed, quality, and sustainability.

Practical metrics you can measure quickly:

Because the hidden work is usually in what you already own: existing services, internal SDKs, CI/CD patterns, deployment gates, observability, and runtime constraints.

If a new language forces you to rebuild your toolchain and ops practices, delivery speed often drops for months.

Focus on the “boring essentials” and daily workflow:

Two big ones:

A practical rule: prefer the option that minimizes time-to-hire + time-to-onboard unless you have a clear domain/performance reason to pay the premium.

Use guardrails that make the right thing automatic:

This reduces reliance on heroics and keeps releases predictable.

Run a short pilot that ships a real slice to production (not a toy): an endpoint + DB + tests + deploy + monitoring.

Track friction end-to-end:

Then decide based on observed results and document the trade-offs and revisit date.