Dec 06, 2025·8 min

Bill Gates and the PC Software Model that Built Dev Ecosystems

How Bill Gates’ PC-era software model linked tools, platforms, and distribution—helping mainstream developers ship apps at scale and shaping modern ecosystems.

How Bill Gates’ PC-era software model linked tools, platforms, and distribution—helping mainstream developers ship apps at scale and shaping modern ecosystems.

The “PC software model” wasn’t a single product or a clever licensing trick. It was a repeatable way for an entire market to work: how developers built software, how they shipped it to users, and how they made money from it.

That sounds basic—until you remember how unusual it was at the start of personal computing. Early computers were often sold as self-contained systems with proprietary hardware, one-off operating environments, and unclear paths for third-party developers. The PC era changed that by turning software into something that could scale beyond any one machine—or any one company.

In practical terms, a software model is the set of assumptions that answers:

When those answers are predictable, developers invest. When they’re not, they hesitate.

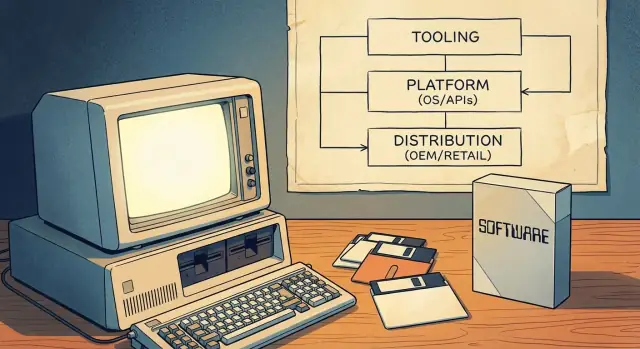

The PC software model worked because it tied together three pillars into a flywheel:

Together, these made the PC a dependable “place to build.” That dependability turned personal computing into a mainstream developer ecosystem—not just a hobbyist scene.

Before mass-market PCs, “computing” usually meant mainframes and minicomputers owned by governments, universities, and large companies. Access was scarce, expensive, and often mediated through IT departments. If you were a developer, you wrote software for a specific organization—not for a broad public market.

Early personal and hobbyist systems did exist, but they didn’t form a single dependable market. Hardware varied widely (CPU families, disk formats, graphics, peripherals), and operating systems were inconsistent or proprietary. A program that ran on one machine often required a rewrite to run on another.

That fragmentation shaped software economics:

Because the addressable audience for any single configuration was small, independent developers had a hard time justifying the time and cost to build polished, widely supported products. Distribution was also constrained: you might ship tapes or disks directly to a customer, rely on user groups, or share code informally. None of this looked like a scalable business.

When PCs became common consumer and office products, the value shifted from one-off deployments to repeatable software sales. The key idea was a standard target: a predictable combination of hardware expectations, operating system conventions, and distribution paths that developers could bet on.

Once a critical mass of buyers and compatible machines existed, writing software became less about “Will this run anywhere else?” and more about “How fast can we reach everyone using this standard?”

Before Microsoft was synonymous with operating systems, it was strongly identified with programming languages—especially BASIC. That choice wasn’t incidental. If you want an ecosystem, you first need people who can build things, and languages are the lowest-friction on-ramp.

Early microcomputers often shipped with BASIC in ROM, and Microsoft’s versions became a familiar entry point across many machines. For a student, hobbyist, or small business tinkerer, the path was simple: turn the machine on, get a prompt, type code, see results. That immediacy mattered more than elegance. It made programming feel like a normal use of a computer, not a specialized profession.

By focusing on approachable tools, Microsoft helped widen the funnel of potential developers. More people writing small programs meant more experiments, more local “apps,” and more demand for better tools. This is an early example of developer mindshare acting like compound interest: once a generation learns on your language and tooling, they tend to keep building—and buying—within that orbit.

The microcomputer era was fragmented, but Microsoft carried consistent ideas from platform to platform: similar language syntax, similar tooling expectations, and a growing sense that “if you can program here, you can probably program there too.” That predictability reduced the perceived risk of learning to code.

The strategic lesson is straightforward: platforms don’t start with marketplaces or monetization. They start with tools that make creation feel possible—and then they earn loyalty by making that experience repeatable.

A big unlock in early personal computing was the “standard OS layer” idea: instead of writing a separate version of your app for every hardware combination, you could target one common interface. For developers, that meant fewer ports, fewer support calls, and a clearer path to shipping something that worked for lots of customers.

MS-DOS sat between applications and the messy variety of PC hardware. You still had different graphics cards, printers, disk controllers, and memory configurations—but MS-DOS provided a shared baseline for file access, program loading, and basic device interaction. That common layer turned “the PC” into a single, addressable market rather than a collection of near-compatible machines.

For customers, compatibility meant confidence: if a program said it ran on MS-DOS (and, by extension, IBM PC compatibles), it was more likely to run on their machine too. For developers, compatibility meant predictable behavior—documented system calls, a stable execution model, and conventions for how programs were installed and launched.

This predictability made it rational to invest in polish, documentation, and ongoing updates, because the audience wasn’t limited to one hardware vendor’s users.

Standardization also created a constraint: keeping old software working became a priority. That backwards-compatibility pressure can slow major changes, because breaking popular programs breaks trust in the platform. The upside is a compounding software library; the downside is a narrower lane for radical OS-level innovation without careful transition plans.

Windows didn’t just sit “on top of” MS-DOS—it changed what developers could assume about the machine. Instead of every program inventing its own way to draw screens, handle input, and talk to peripherals, Windows offered a shared UI model plus a growing set of system services.

The headline change was the graphical user interface: windows, menus, dialogs, and fonts that looked and behaved consistently across apps. That mattered because consistency lowered the “reinvent the basics” tax. Developers could spend time on features users cared about, not on building yet another UI toolkit.

Windows also expanded common services that were painful in the DOS era:

Windows conventions—like standard keyboard shortcuts, dialog layouts, and common controls (buttons, lists, text boxes)—reduced development effort and user training at the same time. Shared components meant fewer bespoke solutions and fewer compatibility surprises when hardware changed.

As Windows evolved, developers had to choose: support older versions for reach, or adopt newer APIs for better capabilities. That planning shaped roadmaps, testing, and marketing.

Over time, tools, documentation, third‑party libraries, and user expectations started to center on Windows as the default target—not just an operating system, but a platform with norms and momentum.

A platform doesn’t feel “real” to developers until it’s easy to ship software on it. In the PC era, that ease was shaped less by marketing and more by the day-to-day experience of writing, building, debugging, and packaging programs.

Compilers, linkers, debuggers, and build systems quietly set the pace of an ecosystem. When compile times drop, error messages improve, and debugging gets reliable, developers can iterate faster—and iteration is what turns a half-working idea into a product.

Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) pushed this further by bundling editing, building, debugging, and project management into one workflow. A good IDE reduced the “glue work” that otherwise consumed hours: setting include paths, managing libraries, keeping builds consistent, and tracking down runtime crashes.

Better tools aren’t just “nice to have”—they change the economics for small teams. If one or two developers can build and test with confidence, they can take on projects that would otherwise require a larger staff. This lowers cost, shortens schedules, and makes it less risky for a tiny ISV to bet on a new product.

Documentation and runnable samples act like a second product: they teach the mental model, show best practices, and prevent common mistakes. Many developers don’t adopt an API because it’s powerful—they adopt it because there’s a clear example that works on day one.

Tool vendors influence which programming models win by making certain paths frictionless. If the templates, wizards, libraries, and debugging views point toward a particular approach, that approach becomes the default—not because it’s theoretically superior, but because it’s faster to learn and safer to ship.

An operating system isn’t automatically a “platform.” It becomes one when outside developers can predictably build on top of it. That’s where APIs and SDKs mattered in the PC era.

An API is basically a menu of features an app can use: draw a window, print a document, save a file, talk to hardware, play sound. Instead of every developer inventing their own way to do these things, the platform offers shared building blocks.

An SDK (software development kit) is the bundle that makes those building blocks usable: the libraries, headers, tools, documentation, and example code that show how to order from the menu.

Developers take on real cost when they build software: time, hiring, support, marketing, and ongoing updates. Stable APIs reduce the risk that an update will suddenly break core functions.

When the rules stay consistent—file dialogs behave the same, printing works the same, window controls follow the same pattern—third-party companies can plan multi-year roadmaps. That predictability is a big reason the Windows developer model attracted serious ISVs rather than only hobbyists.

Platform teams don’t just publish APIs; they cultivate adoption. Developer programs, early documentation, betas, and preview releases let software makers test compatibility before a full launch.

That creates a loop: developers find edge cases, the platform fixes them, and the next wave of apps ships with fewer surprises. Over time, this improves quality for users and lowers support costs for everyone.

APIs can also become a liability. Breaking changes force expensive rewrites. Inconsistent guidelines (different UI conventions across system apps) make third-party apps feel “wrong” even when they work. And fragmentation—multiple overlapping APIs for the same task—splits attention and slows ecosystem momentum.

At scale, the best platform strategy is often boring: clear promises, careful deprecation, and documentation that stays current.

A platform isn’t just APIs and tools—it’s also how software reaches people. In the PC era, distribution decided which products became “default,” which found an audience, and which quietly disappeared.

When PC makers preinstalled software (or bundled it in the box), they shaped user expectations. If a spreadsheet, word processor, or runtime shipped with the machine, it wasn’t merely convenient—it became the starting point. OEM partnerships also reduced friction for buyers: no extra trip to a store, no compatibility guesswork.

For developers, OEM relationships offered something even more valuable than marketing: predictable volume. Shipping with a popular hardware line could mean steady, forecastable sales—especially important for teams that needed to fund support, updates, and documentation.

Retail software boxes, mail-order catalogs, and later big-box computer stores created a “competition for shelf space.” Packaging, brand recognition, and distribution budgets mattered. A better product could lose to a more visible one.

This visibility drove a feedback loop: strong sales justified more shelf presence, which drove more sales. Developers learned that the channel wasn’t neutral—it rewarded products that could scale promotion and support.

Shareware (often distributed on disks via user groups, magazines, and BBS networks) lowered the barrier for new entrants. Users could try software before paying, and small developers could reach niche audiences without retail deals.

The common thread across all these channels was reach and predictability. When developers can count on how customers will discover, try, and buy software, they can plan staffing, pricing, updates, and long-term product bets.

A big reason the PC era pulled in mainstream developers wasn’t just technical possibility—it was predictable economics. The “PC software model” made it easier to forecast revenue, fund ongoing improvements, and build businesses around software rather than services.

Packaged software pricing (and later per-seat licensing) created clear revenue expectations: sell a copy, earn margin, repeat. Periodic paid upgrades mattered because they turned “maintenance” into a business model—developers could plan for new versions every 12–24 months, align marketing with releases, and justify investing in support and documentation.

For small teams, this was huge: you didn’t need a custom contract for every customer. A product could scale.

Once a platform reached a large installed base, it changed which apps were worth making. Niche “vertical” software (accounting for dentists, inventory for auto shops), small utilities, and games became viable because a tiny percentage of a big market can still be a business.

Developers also started optimizing for distribution-friendly products: things that demo well, fit on a shelf, and solve a specific problem quickly.

Small business buyers valued stability over novelty. Compatibility with existing files, printers, and workflows reduced support calls—often the biggest hidden cost for PC software vendors. Platforms that kept older apps running lowered risk for both customers and developers.

An ISV (independent software vendor) was a company whose product depended on someone else’s platform. The trade-off was simple: you gained reach and distribution leverage, but you lived with platform rules, version changes, and support expectations set by the ecosystem.

Network effects are simple: when a platform has more users, it’s easier for developers to justify building apps for it. And when it has more apps, it becomes more valuable to users. That loop is how “good enough” platforms turn into defaults.

In the PC era, choosing where to build wasn’t only about technical elegance. It was about reaching the largest addressable market with the least friction. Once MS‑DOS and later Windows became the common target, developers could ship one product and expect it to run for a large share of customers.

Users followed the software they wanted—spreadsheets, word processors, games—and companies followed the talent pool. Over time, the platform with the deepest catalog felt safer: better hiring, more training materials, more third‑party integrations, and fewer “will it work?” surprises.

Network effects weren’t just about app counts. Standards tightened the loop:

Every standard reduced switching costs for users—and reduced support costs for developers—making the default choice even stickier.

The flywheel breaks when developers can’t succeed:

A platform can have users, but without a reliable path for developers to build, ship, and get paid, the app ecosystem stalls—and the loop reverses.

The PC software model created huge upside for whoever set the “default” environment—but it never meant total control. Microsoft’s rise happened inside a competitive, sometimes unstable, market where other companies could (and did) change the rules.

Apple offered a tightly integrated alternative: fewer hardware combinations, a more controlled user experience, and a different developer story. On the other end, the “IBM-compatible” ecosystem wasn’t a single competitor so much as a sprawling coalition of clone makers, chip vendors, and software publishers—any of which could shift standards or bargaining power.

Even within the IBM orbit, platform direction was contested. OS/2 was a serious attempt to define the next mainstream PC operating environment, and its fate showed how hard it is to migrate developers when the existing target (MS-DOS, then Windows) already has momentum.

Later, the browser era introduced a new potential platform layer above the OS, reframing competition around defaults, distribution, and which runtime developers could count on.

Antitrust scrutiny—without getting into legal outcomes—highlights a recurring platform tension: the same moves that simplify life for users (bundled features, preinstalled software, default settings) can narrow the real choices for developers and rivals.

When a bundled component becomes the default, developers often follow the installed base rather than the “best” option. That can accelerate standardization, but it can also freeze out alternatives and reduce experimentation.

Platform growth strategies create ecosystem responsibilities. If you profit from being the default, you’re also shaping the market’s opportunity structure—who can reach users, what gets funded, and how easy it is to build something new. The healthier the platform’s rules and transparency, the more durable the developer trust that ultimately sustains it.

The PC era taught a simple rule: platforms win when they make it easy for developers to reach lots of users. The web and mobile didn’t erase that rule—they rewired the “how.”

Distribution, updates, and discovery moved online. Instead of shipping boxes to retail shelves (or mailing disks), software became a download. That reduced friction, enabled frequent updates, and introduced new ways to be found: search, links, social sharing, and later algorithmic feeds.

On mobile, app stores became the default channel. They simplified install and payments, but they also created new gatekeepers: review guidelines, ranking systems, and revenue shares. In other words, distribution got easier and more centralized at the same time.

Open source and cross-platform tooling lowered lock-in. A developer can build on macOS or Linux, use free toolchains, and ship to multiple environments. Browsers, JavaScript, and common frameworks also shifted power away from any single OS vendor by making “runs anywhere” more realistic for many categories of apps.

Developers still follow the easiest path to users.

That path is shaped by:

When those pieces are aligned, ecosystems grow—whether the “platform” is Windows, a browser, an app store, or an AI-native builder.

You don’t need to recreate the PC era to benefit from its playbook. The enduring lesson is that platforms win when they reduce uncertainty for third‑party builders—technical, commercial, and operational.

Start with the basics that make teams comfortable betting their roadmap on yours:

Treat developers as a primary customer segment. That means:

If you want examples of how business model choices affect partner behavior, compare approaches in /blog and /pricing.

One reason the PC model remains a useful lens is that it maps cleanly onto newer “vibe-coding” platforms.

For example, Koder.ai makes a strong bet on the same three pillars:

The platform also reflects a newer version of PC-era economics: tiered pricing (free, pro, business, enterprise), source code export, and incentives like credits for published content or referrals—concrete mechanisms that make building (and continuing to build) financially rational.

Short-term control can create long-term hesitation. Watch for patterns that make partners feel replaceable: copying successful apps, sudden policy changes, or breaking integrations without a migration path.

Aim for long-term compatibility where possible. When breaking changes are unavoidable, provide tooling, timelines, and incentives to move—so developers feel protected, not punished.

It’s the repeatable set of assumptions that makes software a scalable business on a platform: a stable target to build for, reliable tools and documentation to build efficiently, and predictable ways to distribute and get paid.

When those three stay consistent over time, developers can justify investing in polish, support, and long-term roadmaps.

Because fragmentation makes everything expensive: more ports, more QA matrices, more support issues, and a smaller reachable audience per build.

Once MS‑DOS/IBM-compatible PCs became a common target, developers could ship one product to a much larger installed base, which made “product software” economics work.

Tools determine iteration speed and confidence. Better compilers, debuggers, IDEs, docs, and samples reduce the time from idea → working build → shippable product.

Practically, that means:

BASIC made programming immediate: turn on the computer, get a prompt, write code, see results.

That low-friction on-ramp expanded the creator pool (students, hobbyists, small businesses). A larger creator pool then increases demand for more tools, libraries, and platform capabilities—fueling an ecosystem.

MS‑DOS provided a shared baseline for key behaviors like program loading and file access, so “runs on MS‑DOS” became a meaningful compatibility promise.

Even with varied hardware, that common OS layer reduced porting work and gave customers confidence that software would likely run on their machines.

Windows standardized the UI and expanded common system services so every app didn’t need to reinvent basic building blocks.

In practice, developers could rely on:

APIs are the capabilities apps call into (UI, files, printing, networking). SDKs package what developers need to use those APIs (headers/libraries, tools, docs, samples).

Stable APIs turn curiosity into investment because they lower the risk that an OS update will break core app behavior.

Backwards compatibility keeps old software working, which preserves trust and protects the value of the existing software library.

The trade-off is slower, riskier platform change. If breaking changes are necessary, the practical best practice is clear deprecation policies, migration tooling, and timelines so developers can plan upgrades.

Each channel shaped adoption differently:

The key is predictability—developers build businesses when they can forecast how customers will find, install, and pay.

An ISV (independent software vendor) sells software built on top of someone else’s platform.

You gain reach (large installed base, familiar distribution) but accept platform risk:

Mitigation usually means testing across versions, watching platform roadmaps, and avoiding over-dependence on unstable interfaces.