Sep 27, 2025·8 min

Blue/Green & Canary Deployments: A Clear Release Strategy

Learn when to use Blue/Green vs Canary deployments, how traffic shifting works, what to monitor, and practical rollout and rollback steps for safer releases.

What Blue/Green and Canary Deployments Mean

Shipping new code is risky for a simple reason: you don’t truly know how it behaves until real users hit it. Blue/Green and Canary are two common ways to reduce that risk while keeping downtime close to zero.

Blue/Green in plain terms

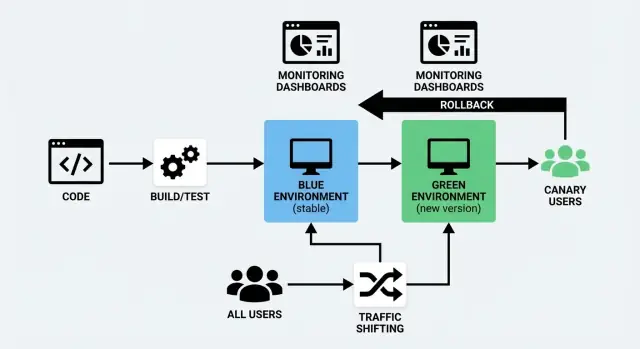

A blue/green deployment uses two separate but similar environments:

- Blue: the version currently serving users (the “live” setup).

- Green: a second, ready-to-go setup where you deploy the new version.

You prepare the Green environment in the background—deploy the new build, run checks, warm it up—then you switch traffic from Blue to Green when you’re confident. If something goes wrong, you can switch back quickly.

The key idea isn’t “two colors,” it’s a clean, reversible cutover.

Canary in plain terms

A canary release is a gradual rollout. Instead of switching everyone at once, you send the new version to a small slice of users first (for example, 1–5%). If everything looks healthy, you expand the rollout step by step until 100% of traffic is on the new version.

The key idea is learning from real traffic before you fully commit.

The shared goal: safer releases with less downtime

Both approaches are deployment strategies that aim to:

- reduce user impact when something breaks

- support a zero downtime deploy (or as close as your system allows)

- make rollbacks less stressful and more predictable

They do this in different ways: Blue/Green focuses on a fast switch between environments, while Canary focuses on controlled exposure through traffic shifting.

No single “best” option

Neither approach is automatically superior. The right choice depends on how your product is used, how confident you are in your testing, how quickly you need feedback, and what kind of failures you’re trying to avoid.

Many teams also mix them—using Blue/Green for infrastructure simplicity and Canary techniques for gradual user exposure.

In the next sections, we’ll compare them directly and show when each one tends to work best.

Blue/Green vs Canary: Quick Comparison

Blue/Green and Canary are both ways to release changes without interrupting users—but they differ in how traffic moves to the new version.

How traffic switches

Blue/Green runs two full environments: “Blue” (current) and “Green” (new). You validate Green, then switch all traffic at once—like flipping a single, controlled switch.

Canary releases the new version to a small slice of users first (for example 1–5%), then shifts traffic gradually as you watch real-world performance.

Pros and cons that actually matter

| Factor | Blue/Green | Canary |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Very fast cutover after validation | Slower by design (ramped rollout) |

| Risk | Medium: a bad release affects everyone after the switch | Lower: issues often show up before full rollout |

| Complexity | Moderate (two environments, clean switch) | Higher (traffic splitting, analysis, gradual steps) |

| Cost | Higher (you’re effectively doubling capacity during rollout) | Often lower (you can ramp using existing capacity) |

| Best for | Big, coordinated changes | Frequent, small improvements |

A simple decision guideline

Choose Blue/Green when you want a clean, predictable moment to cut over—especially for larger changes, migrations, or releases that require a firm “old vs new” separation.

Choose Canary when you ship often, want to learn from real usage safely, and prefer to reduce blast radius by letting metrics guide each step.

If you’re unsure, start with Blue/Green for operational simplicity, then add Canary for higher-risk services once monitoring and rollback habits are solid.

When Blue/Green Is the Right Fit

Blue/Green is a strong choice when you want releases to feel like a “flip of a switch.” You run two production-like environments: Blue (current) and Green (new). When Green is verified, you route users to it.

You need near-zero downtime

If your product can’t tolerate visible maintenance windows—checkout flows, booking systems, logged-in dashboards—Blue/Green helps because the new version is started, warmed up, and checked before real users are sent over. Most of the “deploy time” happens off to the side, not in front of customers.

You want the simplest rollback possible

Rollback is often just routing traffic back to Blue. That’s valuable when:

- a release must be reversible within minutes

- you want to avoid emergency hotfixes under pressure

- you need a clear, repeatable failure response

The key benefit is that rollback doesn’t require rebuilding or redeploying—it’s a traffic switch.

Your database changes can be kept compatible

Blue/Green is easiest when database migrations are backward compatible, because for a short period Blue and Green may both exist (and may both read/write, depending on your routing and job setup).

Good fits include:

- additive schema changes (new nullable columns, new tables)

- expanding data formats in a way old code can ignore

Risky fits include removing columns, renaming fields, or changing meanings in place—those can break the “switch back” promise unless you plan multi-step migrations.

You can afford duplicate environments and routing control

Blue/Green requires extra capacity (two stacks) and a way to direct traffic (load balancer, ingress, or platform routing). If you already have automation to provision environments and a clean routing lever, Blue/Green becomes a practical default for high-confidence, low-drama releases.

When Canary Releases Make More Sense

A canary release is a deployment strategy where you roll out a change to a small slice of real users first, learn from what happens, then expand. It’s the right choice when you want to reduce risk without stopping the world for a big “all at once” release.

You have lots of traffic—and clear signals

Canary works best for high-traffic apps because even 1–5% of traffic can produce meaningful data quickly. If you already track clear metrics (error rate, latency, conversion, checkout completion, API timeouts), you can validate the release on real usage patterns instead of relying only on test environments.

You’re worried about performance and edge cases

Some issues only show up under real load: slow database queries, cache misses, regional latency, unusual devices, or rare user flows. With a canary release, you can confirm the change doesn’t increase errors or degrade performance before it reaches everyone.

You need staged rollouts, not a single cutover

If your product ships frequently, has multiple teams contributing, or includes changes that can be gradually introduced (UI tweaks, pricing experiments, recommendation logic), canary rollouts fit naturally. You can expand from 1% → 10% → 50% → 100% based on what you see.

Feature flags are part of your toolkit

Canary pairs especially well with feature flags: you can deploy code safely, then enable functionality for a subset of users, regions, or accounts. That makes rollbacks less dramatic—often you can simply turn a flag off instead of redeploying.

If you’re building toward progressive delivery, canary releases are often the most flexible starting point.

See also: /blog/feature-flags-and-progressive-delivery

Traffic Shifting Basics (Without the Jargon)

Traffic shifting simply means controlling who gets the new version of your app and when. Instead of flipping everyone over at once, you move requests gradually (or selectively) from the old version to the new one. This is the practical heart of both a blue/green deployment and a canary release—and it’s also what makes a zero downtime deploy realistic.

The “steering wheel”: where traffic gets routed

You can shift traffic at a few common points in your stack. The right choice depends on what you already run and how fine-grained you need control to be.

- Load balancer: splits incoming requests between two environments or two sets of servers.

- Ingress controller (Kubernetes): routes traffic to different Services based on rules.

- Service mesh: controls traffic between services with precise rules and better visibility.

- CDN / edge routing: useful when you want routing decisions close to users, often for web traffic.

You don’t need every layer. Pick one “source of truth” for routing decisions so your release management doesn’t become guesswork.

Common ways to split traffic

Most teams use one (or a mix) of these approaches for traffic shifting:

- Percentage-based: 1% → 5% → 25% → 50% → 100%. This is the classic canary pattern.

- Header-based: route requests with a specific header (for example, from QA tools or internal testers) to the new version.

- User cohorts: shift specific groups first—employees, beta users, a region, or a customer tier.

Percentage is easiest to explain, but cohorts are often safer because you can control which users see the change (and avoid surprising your biggest customers during the first hour).

Sessions and caches: the two “gotchas”

Two things commonly break otherwise solid deployment plans:

Sticky sessions (session affinity). If your system ties a user to one server/version, a 10% traffic split might not behave like 10%. It can also cause confusing bugs when users bounce between versions mid-session. If you can, use shared session storage or ensure routing keeps a user consistently on one version.

Cache warming. New versions often hit cold caches (CDN, application cache, database query cache). That can look like a performance regression even when the code is fine. Plan time to warm caches before ramping traffic, especially for high-traffic pages and expensive endpoints.

Make traffic changes a controlled operation

Treat routing changes like production changes, not an ad-hoc button click.

Document:

- who is allowed to change traffic splits

- how it’s approved (on-call? release manager? change ticket?)

- where it’s done (load balancer config, ingress rules, mesh policy)

- what “stop” looks like (the trigger to pause the rollout and follow the rollback plan)

This small bit of governance prevents well-meaning people from “just nudging it to 50%” while you’re still figuring out whether the canary is healthy.

What to Monitor During a Rollout

Launch On Your Domain

Go live on your own domain when you are ready to promote a new version.

A rollout isn’t just “did the deploy succeed?” It’s “are real users getting a worse experience?” The easiest way to stay calm during Blue/Green or Canary is to watch a small set of signals that tell you: is the system healthy, and is the change hurting customers?

The four core signals: errors, latency, saturation, user impact

Error rate: Track HTTP 5xx, request failures, timeouts, and dependency errors (database, payments, third-party APIs). A canary that increases “small” errors can still create big support load.

Latency: Watch p50 and p95 (and p99 if you have it). A change that keeps average latency stable can still create long-tail slowdowns that users feel.

Saturation: Look at how “full” your system is—CPU, memory, disk IO, DB connections, queue depth, thread pools. Saturation problems often show up before full outages.

User-impact signals: Measure what users actually experience—checkout failures, sign-in success rate, search results returned, app crash rate, key page load times. These are often more meaningful than infrastructure stats alone.

Build a “release dashboard” everyone can read

Create a small dashboard that fits on one screen and is shared in your release channel. Keep it consistent across every rollout so people don’t waste time hunting for graphs.

Include:

- error rate (overall + key endpoints)

- latency (p50/p95 for critical paths)

- saturation (top 3 constraints for your stack, e.g., app CPU, DB connections, queue depth)

- user-impact KPIs (your top 1–3 business-critical flows)

If you run a canary release, segment metrics by version/instance group so you can compare canary vs baseline directly. For blue/green deployment, compare the new environment vs the old during the cutover window.

Set clear thresholds for pause/rollback decisions

Decide the rules before you start shifting traffic. Example thresholds might be:

- error rate increases by X% over baseline for Y minutes

- p95 latency exceeds a fixed limit (or rises X% over baseline)

- a user-impact KPI drops below a minimum acceptable value

The exact numbers depend on your service, but the important part is agreement. If everyone knows the rollback plan and the triggers, you avoid debate while customers are affected.

Alerts that focus on the rollout window

Add (or temporarily tighten) alerts specifically during rollout windows:

- unexpected spikes in 5xx/timeouts

- sudden latency regression on key routes

- rapid growth in saturation signals (connection pools, queues)

Keep alerts actionable: “what changed, where, and what to do next.” If your alerting is noisy, people will miss the one signal that matters when traffic shifting is underway.

Pre-Release Checks That Catch Problems Early

Most rollout failures aren’t caused by “big bugs.” They’re caused by small mismatches: a missing config value, a bad database migration, an expired certificate, or an integration that behaves differently in the new environment. Pre-release checks are your chance to catch those issues while the blast radius is still close to zero.

Start with health checks and smoke tests

Before you shift any traffic (whether it’s a blue/green switch or a small canary percentage), confirm the new version is basically alive and able to serve requests.

- Ensure app health endpoints report OK (not just “the process is running”)

- Validate dependencies: database, cache, queue, object storage, email/SMS providers

- Confirm secrets and environment variables are present and correctly scoped

Run quick end-to-end tests against the new environment

Unit tests are great, but they don’t prove the deployed system works. Run a short, automated end-to-end suite against the new environment that finishes in minutes, not hours.

Focus on flows that cross service boundaries (web → API → database → third-party), and include at least one “real” request per key integration.

Verify critical user journeys (the ones that pay the bills)

Automated tests miss the obvious sometimes. Do a targeted, human-friendly verification of your core workflows:

- login and password reset

- checkout or payment flow (including failure paths)

- core “create / update / delete” actions users do every day

If you support multiple roles (admin vs customer), sample at least one journey per role.

Keep a pre-release readiness checklist

A checklist turns tribal knowledge into a repeatable deployment strategy. Keep it short and actionable:

- database migrations applied and reversible (or clearly safe)

- observability ready: logs, dashboards, alerts for key metrics

- rollback plan reviewed (who, how, and what “stop” looks like)

When these checks are routine, traffic shifting becomes a controlled step—not a leap of faith.

Blue/Green Rollout: A Practical Playbook

Build Full Stack Quickly

Generate a React web app with a Go and PostgreSQL backend from a simple chat.

A blue/green rollout is easiest to run when you treat it like a checklist: prepare, deploy, validate, switch, observe, then clean up.

1) Deploy to Green (without touching users)

Ship the new version to the Green environment while Blue continues serving real traffic. Keep configs and secrets aligned so Green is a true mirror.

2) Validate Green before any traffic switch

Do quick, high-signal checks first: app starts cleanly, key pages load, payments/login work, and logs look normal. If you have automated smoke tests, run them now. This is also the moment to verify monitoring dashboards and alerts are active for Green.

3) Plan database migrations the safe way (expand/contract)

Blue/green gets tricky when the database changes. Use an expand/contract approach:

- Expand: add new columns/tables in a backwards-compatible way.

- Deploy Green so it can work with both old and new schema.

- Contract: remove old fields only after Blue is retired and you’re confident the new code is stable.

This avoids a “Green works, Blue breaks” situation during the switch.

4) Warm caches and handle background jobs

Before switching traffic, warm critical caches (home page, common queries) so users don’t pay the “cold start” cost.

For background jobs/cron workers, decide who runs them:

- run jobs in one environment only during the cutover to avoid double-processing

5) Switch traffic, then observe

Flip routing from Blue to Green (load balancer/DNS/ingress). Watch error rate, latency, and business metrics for a short window.

6) Post-switch verification and cleanup

Do a real-user-style spot check, then keep Blue available briefly as a fallback. Once stable, disable Blue jobs, archive logs, and deprovision Blue to reduce cost and confusion.

Canary Rollout: A Practical Playbook

A canary rollout is about learning safely. Instead of sending all users to the new version at once, you expose a small slice of real traffic, watch closely, and only then expand. The goal isn’t “go slow”—it’s “prove it’s safe” with evidence at each step.

A simple ramp plan (1–5% → 25% → 50% → 100%)

- Prepare the canary

Deploy the new version alongside the current stable version. Make sure you can route a defined percentage of traffic to each one, and that both versions are visible in monitoring (separate dashboards or tags help).

- Stage 1: 1–5%

Start tiny. This is where obvious issues show up fast: broken endpoints, missing configs, database migration surprises, or unexpected latency spikes.

Keep notes for the stage:

- what changed in this release (including “small” config changes)

- what you expected to happen

- what you observed (errors, latency, user-impacting issues)

- Stage 2: 25%

If the first stage is clean, increase to around a quarter of traffic. You’ll now see more “real world” variety: different user behaviors, long-tail devices, edge cases, and higher concurrency.

- Stage 3: 50%

Half traffic is where capacity and performance issues become clearer. If you’re going to hit a scaling limit, you’ll often see early warning signs here.

- Stage 4: 100% (promotion)

When metrics are stable and user impact is acceptable, shift all traffic to the new version and declare it promoted.

Choosing ramp intervals (how long to wait at each step)

Ramp timing depends on risk and traffic volume:

- High-risk change or low traffic: wait longer per stage to get enough signal (e.g., 30–60 minutes, sometimes more). Low-traffic services may need hours to see meaningful patterns.

- Low-risk change with high traffic: shorter stages can work (e.g., 5–15 minutes), because you’ll collect data quickly.

Also consider business cycles. If your product has spikes (like lunchtime, weekends, billing runs), run the canary long enough to cover the conditions that typically cause trouble.

Automate promotion and rollback

Manual rollouts create hesitation and inconsistency. Where possible, automate:

- promotion when key metrics stay within thresholds for a defined window

- rollback when thresholds are violated (for example, error rate or latency crosses a limit)

Automation doesn’t remove human judgment—it removes delay.

Treat each stage like an experiment

For every ramp step, write down:

- change summary (what exactly is different)

- success criteria (which metrics must remain stable)

- observed results (what you saw, including “nothing unusual”)

- decision (promote, hold, or rollback) and why

These notes turn your rollout history into a playbook for the next release—and make future incidents far easier to diagnose.

Rollback Plans and Failure Handling

Rollbacks are easiest when you decide in advance what “bad” looks like and who is allowed to press the button. A rollback plan isn’t pessimism—it’s how you keep small issues from turning into prolonged outages.

Define clear rollback triggers

Pick a short list of signals and set explicit thresholds so you don’t debate during an incident. Common triggers include:

- error rate: spikes in 5xx errors, failed checkouts, login failures, or API timeouts

- latency: p95/p99 latency over an agreed limit for a sustained window (for example, 5–10 minutes)

- business KPIs: sudden drops in conversion, payment success, sign-ups, or increases in cancellations

Make the trigger measurable (“p95 > 800ms for 10 minutes”) and tie it to an owner (on-call, release manager) with permission to act immediately.

Keep rollback fast (and boring)

Speed matters more than elegance. Your rollback should be one of these:

- reverse the traffic shift (typical for blue/green and canary): move traffic back to the previous, known-good version

- redeploy the previous version: if infrastructure changed, push the last stable build and re-run health checks

Avoid “manual fix then continue rollout” as your first move. Stabilize first, investigate second.

Plan for partial rollouts

With a canary release, some users may have created data under the new version. Decide ahead of time:

- Do “canary” users get routed back immediately, or kept on the canary while you assess?

- If data formats changed, is the database backward-compatible? If not, rollback might require a separate mitigation.

After-action review that improves the next release

Once stable, write a short after-action note: what triggered the rollback, what signals were missing, and what you’ll change in the checklist. Treat it as a product improvement cycle for your release process, not a blame exercise.

Feature Flags and Progressive Delivery

Make Releases Routine

Keep deployments repeatable with hosting that fits an app you generate and ship often.

Feature flags let you separate “deploy” (shipping code to production) from “release” (turning it on for people). That’s a big deal because you can use the same deployment pipeline—blue/green or canary—while controlling exposure with a simple switch.

Deploy without pressure, release with intent

With flags, you can merge and deploy safely even if a feature isn’t ready for everyone. The code is present, but dormant. When you’re confident, you enable the flag gradually—often faster than pushing a new build—and if something goes wrong, you can disable it just as quickly.

Targeted enablement (not all-or-nothing)

Progressive delivery is about increasing access in deliberate steps. A flag can be enabled for:

- a specific user group (internal staff, beta users, paid tier)

- a region (start with one country or data center)

- a percentage of users (1% → 10% → 50% → 100%)

This is especially helpful when a canary rollout tells you the new version is healthy, but you still want to manage the feature risk separately.

Guardrails that prevent “flag debt”

Feature flags are powerful, but only if they’re governed. A few guardrails keep them tidy and safe:

- ownership: every flag has an accountable team or person

- expiration: set a removal date (or review date) so old flags don’t pile up

- documentation: write what the flag does, who it affects, and how to roll it back

A practical rule: if someone can’t answer “what happens when we turn this off?” the flag isn’t ready.

For deeper guidance on using flags as part of a release strategy, see /blog/feature-flags-release-strategy.

How to Choose Your Strategy and Get Started

Choosing between blue/green and canary isn’t about “which is better.” It’s about what kind of risk you want to control, and what you can realistically operate with your current team and tooling.

A quick way to decide

If your top priority is a clean, predictable cutover and an easy “back to the old version” button, blue/green is usually the simplest fit.

If your top priority is reducing blast radius and learning from real user traffic before going wider, canary is the safer fit—especially when changes are frequent or hard to fully test ahead of time.

A practical rule: start with the approach your team can run consistently at 2 a.m. when something goes wrong.

Start small: pilot one thing

Pick one service (or one user-facing workflow) and run a pilot for a few releases. Choose something important enough to matter, but not so critical that everyone freezes. The goal is to build muscle memory around traffic shifting, monitoring, and rollback.

Write a simple runbook (and assign ownership)

Keep it short—one page is fine:

- what “good” looks like (key metrics and thresholds)

- who is on point during a rollout

- how to pause, rollback, and communicate

Make sure ownership is clear. A strategy without an owner becomes a suggestion.

Use what you already have first

Before adding new platforms, look at the tools you already rely on: load balancer settings, deployment scripts, existing monitoring, and your incident process. Add new tooling only when it removes real friction you’ve felt in the pilot.

If you’re building and shipping new services quickly, platforms that combine app generation with deployment controls can also reduce operational drag. For example, Koder.ai is a vibe-coding platform that lets teams create web, backend, and mobile apps from a chat interface—and then deploy and host them with practical safety features like snapshots and rollback, plus support for custom domains and source code export. Those capabilities map well to the core goal of this article: make releases repeatable, observable, and reversible.

Suggested next steps

If you want to see implementation options and supported workflows, review /pricing and /docs/deployments. Then schedule your first pilot release, capture what worked, and iterate your runbook after every rollout.