Oct 02, 2025·8 min

Brendan Burns and Kubernetes: Ideas That Shaped Orchestration

A practical look at Brendan Burns’ Kubernetes-era orchestration ideas—declarative state, controllers, scaling, and service operations—and why they became standard.

A practical look at Brendan Burns’ Kubernetes-era orchestration ideas—declarative state, controllers, scaling, and service operations—and why they became standard.

Kubernetes didn’t just introduce a new tool—it changed what “day-to-day ops” looks like when you’re running dozens (or hundreds) of services. Before orchestration, teams often stitched together scripts, manual runbooks, and tribal knowledge to answer the same recurring questions: Where should this service run? How do we roll out a change safely? What happens when a node dies at 2 a.m.?

At its core, orchestration is the coordination layer between your intent (“run this service like this”) and the messy reality of machines failing, traffic shifting, and deployments happening continuously. Instead of treating each server as a special snowflake, orchestration treats compute as a pool and workloads as schedulable units that can move.

Kubernetes popularized a model where teams describe what they want, and the system continually works to make reality match that description. That shift matters because it makes operations less about heroics and more about repeatable processes.

Kubernetes standardized operational outcomes that most service teams need:

This article focuses on the ideas and patterns associated with Kubernetes (and leaders like Brendan Burns), not a personal biography. And when we talk about “how it started” or “why it was designed this way,” those claims should be grounded in public sources—conference talks, design docs, and upstream documentation—so the story stays verifiable rather than myth-based.

Brendan Burns is widely recognized as one of the three original co-founders of Kubernetes, alongside Joe Beda and Craig McLuckie. In early Kubernetes work at Google, Burns helped shape both the technical direction and the way the project was explained to users—especially around “how you operate software” rather than just “how you run containers.” (Sources: Kubernetes: Up & Running, O’Reilly; Kubernetes project repository AUTHORS/maintainers listings)

Kubernetes wasn’t simply “released” as a finished internal system; it was built in public with a growing set of contributors, use cases, and constraints. That openness pushed the project toward interfaces that could survive different environments:

This collaborative pressure matters because it influenced what Kubernetes optimized for: shared primitives and repeatable patterns that lots of teams could agree on, even if they disagreed on tools.

When people say Kubernetes “standardized” deployment and operations, they usually don’t mean it made every system identical. They mean it provided a common vocabulary and a set of workflows that can be repeated across teams:

That shared model made it easier for docs, tooling, and team practices to transfer from one company to another.

It’s useful to separate Kubernetes (the open-source project) from the Kubernetes ecosystem.

The project is the core API and control plane components that implement the platform. The ecosystem is everything that grew around it—distributions, managed services, add-ons, and adjacent CNCF projects. Many real-world “Kubernetes features” people rely on (observability stacks, policy engines, GitOps tools) live in that ecosystem, not in the core project itself.

Declarative configuration is a simple shift in how you describe systems: instead of listing the steps to take, you state what you want the end result to be.

In Kubernetes terms, you don’t tell the platform “start a container, then open a port, then restart it if it crashes.” You declare “there should be three copies of this app running, reachable on this port, using this container image.” Kubernetes takes responsibility for making reality match that description.

Imperative operations are like a runbook: a sequence of commands that worked last time, executed again when something changes.

Desired state is closer to a contract. You record the intended outcome in a configuration file, and the system continually works toward that outcome. If something drifts—an instance dies, a node disappears, a manual change sneaks in—the platform detects the mismatch and corrects it.

Before (imperative runbook thinking):

This approach is workable, but it’s easy to end up with “snowflake” servers and a long checklist that only a few people trust.

After (declarative desired state):

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: checkout

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: checkout

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: checkout

spec:

containers:

- name: app

image: example/checkout:1.2.3

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

You change the file (for example, update image or replicas), apply it, and Kubernetes’ controllers work to reconcile what’s running with what’s declared.

Declarative desired state lowers operational toil by turning “do these 17 steps” into “keep it like this.” It also reduces configuration drift because the source of truth is explicit and reviewable—often in version control—so surprises are easier to spot, audit, and roll back consistently.

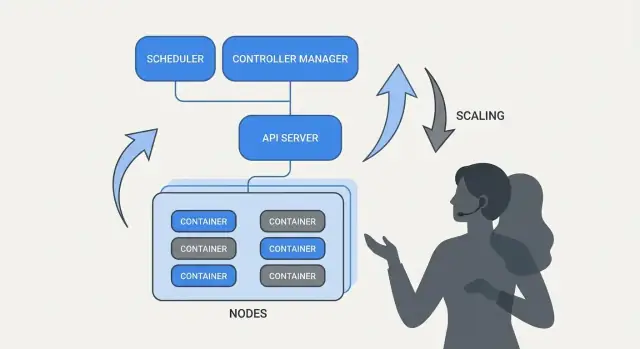

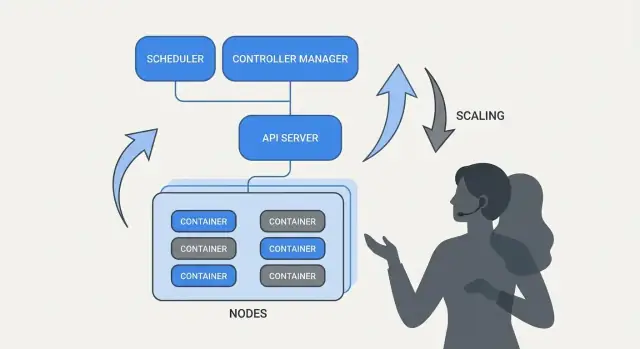

Kubernetes feels “self-managing” because it’s built around a simple pattern: you describe what you want, and the system continuously works to make reality match that description. The engine of that pattern is the controller.

A controller is a loop that watches the current state of the cluster and compares it to the desired state you declared in YAML (or via an API call). When it spots a gap, it takes action to reduce that gap.

It’s not a one-time script and it’s not waiting for a human to click a button. It runs repeatedly—observe, decide, act—so it can respond to change at any moment.

That repeated compare-and-correct behavior is called reconciliation. It’s the mechanism behind the common promise of “self-healing.” The system doesn’t magically prevent failures; it notices drift and corrects it.

Drift can happen for mundane reasons:

Reconciliation means Kubernetes treats those events as signals to re-check your intent and restore it.

Controllers translate into familiar operational results:

The key is that you’re not manually chasing symptoms. You’re declaring the target, and the control loops do the continuous “keeping it so” work.

This approach isn’t limited to one resource type. Kubernetes uses the same controller-and-reconciliation idea across many objects—Deployments, ReplicaSets, Jobs, Nodes, endpoints, and more. That consistency is a big reason Kubernetes became a platform: once you understand the pattern, you can predict how the system will behave as you add new capabilities (including custom resources that follow the same loop).

If Kubernetes did only “run containers,” it would still leave teams with the hardest part: deciding where each workload should run. Scheduling is the built-in system that places Pods onto the right nodes automatically, based on resource needs and rules you define.

That matters because placement decisions directly affect uptime and cost. A web API stuck on a crowded node can become slow or crash. A batch job placed next to latency-sensitive services can create noisy-neighbor problems. Kubernetes turns this into a repeatable product capability instead of a spreadsheet-and-SSH routine.

At a basic level, the scheduler looks for nodes that can satisfy your Pod’s requests.

This single habit—setting realistic requests—often reduces “random” instability because critical services stop competing with everything else.

Beyond resources, most production clusters rely on a few practical rules:

Scheduling features help teams encode operational intent:

The key practical takeaway: treat scheduling rules like product requirements—write them down, review them, and apply them consistently—so reliability doesn’t depend on someone remembering the “right node” at 2 a.m.

One of Kubernetes’ most practical ideas is that scaling shouldn’t require changing your application code or inventing a new deployment approach. If the app can run as one container, the same workload definition can usually grow to hundreds or thousands of copies.

Kubernetes separates scaling into two related decisions:

That split matters: you can ask for 200 pods, but if the cluster only has room for 50, “scaling” becomes a queue of pending work.

Kubernetes commonly uses three autoscalers, each focused on a different lever:

Used together, this turns scaling into policy: “keep latency stable” or “keep CPU around X%,” rather than a manual paging routine.

Scaling only works as well as the inputs:

Two mistakes show up repeatedly: scaling on the wrong metric (CPU stays low while requests time out) and missing resource requests (autoscalers can’t predict capacity, pods get packed too tightly, and performance becomes inconsistent).

A big shift Kubernetes popularized is treating “deploying” as an ongoing control problem, not a one-time script you run at 5 PM on Friday. Rollouts and rollbacks are first-class behaviors: you declare what version you want, and Kubernetes moves the system toward it while continuously checking whether the change is actually safe.

With a Deployment, a rollout is a gradual replacement of old Pods with new ones. Instead of stopping everything and starting again, Kubernetes can update in steps—keeping capacity available while the new version proves it can handle real traffic.

If the new version starts failing, rollback isn’t an emergency procedure. It’s a normal operation: you can revert to a previous ReplicaSet (the last known good version) and let the controller restore the old state.

Health checks are what turn rollouts from “hope-based” to measurable.

Used well, probes reduce false successes—deployments that look fine because Pods started, but are actually failing requests.

Kubernetes supports a rolling update out of the box, but teams often layer additional patterns on top:

Safe deployments depend on signals: error rate, latency, saturation, and user impact. Many teams connect rollout decisions to SLOs and error budgets—if a canary burns too much budget, promotion stops.

The goal is automated rollback triggers based on real indicators (failed readiness, rising 5xx, latency spikes), so “rollback” becomes a predictable system response—not a late-night hero moment.

A container platform only feels “automatic” if other parts of the system can still find your app after it moves. In real production clusters, pods are created, deleted, rescheduled, and scaled all the time. If every change required updating IP addresses in configs, operations would turn into constant busywork—and outages would be routine.

Service discovery is the practice of giving clients a reliable way to reach a changing set of backends. In Kubernetes, the key shift is that you stop targeting individual instances (“call 10.2.3.4”) and instead target a named service (“call checkout”). The platform handles which pods currently serve that name.

A Service is a stable front door for a group of pods. It has a consistent name and virtual address inside the cluster, even when the underlying pods change.

A selector is how Kubernetes decides which pods are “behind” that front door. Most commonly it matches labels, such as app=checkout.

Endpoints (or EndpointSlices) are the living list of actual pod IPs that currently match the selector. When pods scale up, roll out, or get rescheduled, this list updates automatically—clients keep using the same Service name.

Operationally, this provides:

For north–south traffic (from outside the cluster), Kubernetes typically uses an Ingress or the newer Gateway approach. Both provide a controlled entry point where you can route requests by hostname or path, and often centralize concerns like TLS termination. The important idea is the same: keep external access stable while the backends change underneath.

“Self-healing” in Kubernetes isn’t magic. It’s a set of automated reactions to failure: restart, reschedule, and replace. The platform watches what you said you wanted (your desired state) and keeps nudging reality back toward it.

If a process exits or a container becomes unhealthy, Kubernetes can restart it on the same node. This is usually driven by:

A common production pattern is: a single container crashes → Kubernetes restarts it → your Service keeps routing only to healthy Pods.

If an entire node goes down (hardware issue, kernel panic, lost network), Kubernetes detects the node as unavailable and starts moving work elsewhere. At a high level:

This is “self-healing” at the cluster level: the system replaces capacity, rather than waiting for a human to SSH in.

Self-healing only matters if you can verify it. Teams typically watch:

Even with Kubernetes, the “healing” can fail if the guardrails are wrong:

When self-healing is set up well, outages become smaller and shorter—and more importantly, measurable.

Kubernetes didn’t win only because it could run containers. It won because it offered standard APIs for the most common operational needs—deploying, scaling, networking, and observing workloads. When teams agree on the same “shape” of objects (like Deployments, Services, Jobs), tools can be shared across orgs, training is simpler, and handoffs between dev and ops stop relying on tribal knowledge.

A consistent API means your deployment pipeline doesn’t have to know the quirks of every app. It can apply the same actions—create, update, roll back, and check health—using the same Kubernetes concepts.

It also improves alignment: security teams can express guardrails as policies; SREs can standardize runbooks around common health signals; developers can reason about releases with a shared vocabulary.

The “platform” shift becomes obvious with Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs). A CRD lets you add a new type of object to the cluster (for example, Database, Cache, or Queue) and manage it with the same API patterns as built-in resources.

An Operator pairs those custom objects with a controller that continuously reconciles reality to the desired state—handling tasks that used to be manual, like backups, failovers, or version upgrades. The key benefit is not magic automation; it’s reusing the same control loop approach Kubernetes applies to everything else.

Because Kubernetes is API-driven, it integrates cleanly with modern workflows:

If you want more practical deployment and ops guides built on these ideas, browse /blog.

The biggest Kubernetes ideas—many associated with Brendan Burns’ early framing—translate well even if you’re running on VMs, serverless, or a smaller container setup.

Write down the “desired state” and let automation enforce it. Whether it’s Terraform, Ansible, or a CI pipeline, treat configuration as the source of truth. The outcome is fewer manual deploy steps and far fewer “it worked on my machine” surprises.

Use reconciliation, not one-off scripts. Instead of scripts that run once and hope for the best, build loops that continually verify key properties (version, config, number of instances, health). This is how you get repeatable ops and predictable recovery after failures.

Make scheduling and scaling explicit product features. Define when and why you add capacity (CPU, queue depth, latency SLOs). Even without Kubernetes autoscaling, teams can standardize scale rules so growth doesn’t require rewriting the app or waking someone up.

Standardize rollouts. Rolling updates, health checks, and quick rollback procedures reduce the risk of changes. You can implement these with load balancers, feature flags, and deployment pipelines that gate releases on real signals.

These patterns won’t fix poor app design, unsafe data migrations, or cost control. You still need versioned APIs, migration plans, budgeting/limits, and observability that ties deploys to customer impact.

Pick one customer-facing service and implement the checklist end-to-end, then expand.

If you’re building new services and want to get to “something deployable” faster, Koder.ai can help you generate a full web/backend/mobile app from a chat-driven spec—typically React on the frontend, Go with PostgreSQL on the backend, and Flutter for mobile—then export the source code so you can apply the same Kubernetes patterns discussed here (declarative configs, repeatable rollouts, and rollback-friendly operations). For teams evaluating cost and governance, you can also review /pricing.

Orchestration coordinates your intent (what should run) with real-world churn (node failures, rolling deploys, scaling events). Instead of managing individual servers, you manage workloads and let the platform place, restart, and replace them automatically.

Practically, it reduces:

Declarative config states the end result you want (e.g., “3 replicas of this image, exposed on this port”), not a step-by-step procedure.

Benefits you can use immediately:

Controllers are continuously running control loops that compare current state vs desired state and act to close the gap.

This is why Kubernetes can “self-manage” common outcomes:

Scheduling decides where each Pod runs based on constraints and available capacity. If you don’t guide it, you can end up with noisy neighbors, hotspots, or replicas co-located on the same node.

Common rules to encode operational intent:

Requests tell the scheduler what a Pod needs; limits cap what it can use. Without realistic requests, placement becomes guesswork and stability often suffers.

A practical starting point:

A Deployment rollout replaces old Pods with new Pods gradually while trying to maintain availability.

To keep rollouts safe:

Kubernetes provides rolling updates by default, but teams often add higher-level patterns:

Choose based on risk tolerance, traffic shape, and how quickly you can detect regressions (error rate/latency/SLO burn).

A Service gives a stable name and virtual address for a changing set of Pods. Labels/selectors determine which Pods are “behind” the Service, and EndpointSlices track the actual Pod IPs.

Operationally, this means:

service-name instead of chasing Pod IPsAutoscaling works best when each layer has clear signals:

Common pitfalls:

CRDs let you define new API objects (e.g., Database, Cache) so you can manage higher-level systems through the same Kubernetes API patterns.

Operators pair CRDs with controllers that reconcile desired state to reality, often automating:

Treat them like production software: evaluate maturity, observability, and failure modes before relying on them.