Dec 30, 2025·8 min

Bug triage with Claude Code: a practical loop for fast fixes

Bug triage with Claude Code using a repeatable loop: reproduce, minimize, identify likely causes, add a regression test, and ship a narrow fix with checks.

What bug triage is and why the loop matters

Bugs feel random when every report turns into a one-off mystery. You poke at the code, try a few ideas, and hope the problem disappears. Sometimes it does, but you don’t learn much, and the same issue shows up again in a different form.

Bug triage is the opposite. It’s a fast way to reduce uncertainty. The goal isn’t to fix everything immediately. The goal is to turn a vague complaint into a clear, testable statement, then make the smallest change that proves the statement is now false.

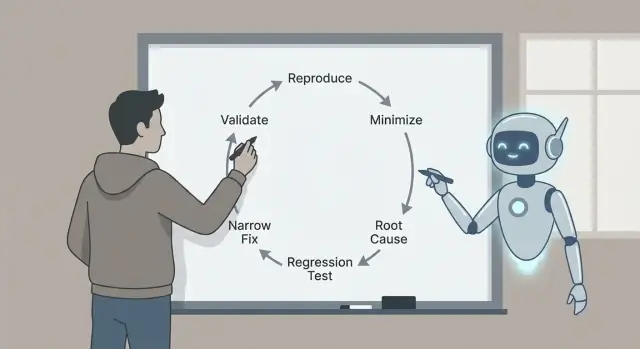

That’s why the loop matters: reproduce, minimize, identify likely causes with evidence, add a regression test, implement a narrow fix, and validate. Each step removes a specific kind of guesswork. Skip steps and you often pay for it later with bigger fixes, side effects, or “fixed” bugs that were never actually fixed.

Here’s a realistic example. A user says: “The Save button sometimes does nothing.” Without a loop, you might rummage through UI code and change timing, state, or network calls. With a loop, you first make “sometimes” become “every time, under these exact conditions,” like: “After editing a title, then quickly switching tabs, Save stays disabled.” That single sentence is already progress.

Claude Code can speed up the thinking part: turning reports into precise hypotheses, suggesting where to look, and proposing a minimal test that should fail. It’s especially helpful at scanning code, logs, and recent diffs to generate plausible explanations quickly.

You still have to verify what matters. Confirm the bug is real in your environment. Prefer evidence (logs, traces, failing tests) over a good-sounding story. Keep the fix as small as possible, prove it with a regression test, and validate it with clear checks so you don’t trade one bug for another.

The payoff is a small, safe fix you can explain, defend, and keep from regressing.

Set up the triage workspace (before touching code)

Good fixes start with a clean workspace and a single, clear problem statement. Before you ask Claude anything, pick one report and rewrite it as:

“When I do X, I expect Y, but I get Z.”

If you can’t write that sentence, you don’t have a bug yet. You have a mystery.

Collect the basics up front so you don’t keep circling back. These details are what make suggestions testable instead of vague: app version or commit (and whether it’s local, staging, or production), environment details (OS, browser/device, feature flags, region), exact inputs (form fields, API payload, user actions), who sees it (everyone, a role, a single account/tenant), and what “expected” means (copy, UI state, status code, business rule).

Then preserve evidence while it’s still fresh. A single timestamp can save hours. Capture logs around the event (client and server if possible), a screenshot or short recording, request IDs or trace IDs, exact timestamps (with timezone), and the smallest snippet of data that triggers the issue.

Example: a Koder.ai-generated React app shows “Payment succeeded” but the order stays “Pending.” Note the user role, the exact order ID, the API response body, and the server log lines for that request ID. Now you can ask Claude to focus on one flow instead of hand-waving.

Finally, set a stopping rule. Decide what will count as fixed before you start coding: a specific test passing, a UI state changing, an error no longer appearing in logs, plus a short validation checklist you’ll run every time. This keeps you from “fixing” the symptom and shipping a new bug.

Turn the bug report into a precise question for Claude

A messy bug report usually mixes facts, guesses, and frustration. Before you ask for help, convert it into a crisp question Claude can answer with evidence.

Start with a one-sentence summary that names the feature and the failure. Good: “Saving a draft sometimes deletes the title on mobile.” Not: “Drafts are broken.” That sentence becomes the anchor for the entire triage thread.

Then separate what you saw from what you expected. Keep it boring and concrete: the exact button you clicked, the message on screen, the log line, the timestamp, the device, the browser, the branch, the commit. If you don’t have those yet, say so.

A simple structure you can paste:

- Summary (one sentence)

- Observed behavior (what happened, including any error text)

- Expected behavior (what should happen)

- Repro steps (numbered, smallest set you know)

- Environment (app version, device, OS, browser, config flags)

If details are missing, ask for them as yes/no questions so people can answer quickly: Does it happen on a fresh account? Only on mobile? Only after a refresh? Did it start after the last release? Can you reproduce in incognito?

Claude is also useful as a “report cleaner.” Paste the original report (including copied text from screenshots, logs, and chat snippets), then ask:

“Rewrite this as a structured checklist. Flag contradictions. List the top 5 missing facts as yes/no questions. Do not guess causes yet.”

If a teammate says “It fails randomly,” push it toward something testable: “Fails 2/10 times on iPhone 14, iOS 17.2, when tapping Save twice quickly.” Now you can reproduce it on purpose.

Step 1 - Reproduce the bug reliably

If you can’t make the bug happen on demand, every next step is guesswork.

Start by reproducing it in the smallest environment that can still show the problem: a local dev build, a minimal branch, a tiny dataset, and as few services turned on as possible.

Write down the exact steps so someone else can follow them without asking questions. Make it copy-paste friendly: commands, IDs, and sample payloads should be included exactly as used.

A simple capture template:

- Setup: branch/commit, config flags, database state (empty, seeded, production copy)

- Steps: numbered actions with exact inputs

- Expected vs actual: what you thought would happen, what happened instead

- Evidence: error text, screenshots, timestamps, request IDs

- Frequency: always, sometimes, first run only, only after a refresh

Frequency changes your strategy. “Always” bugs are great for fast iteration. “Sometimes” bugs often point to timing, caching, race conditions, or hidden state.

Once you have reproduction notes, ask Claude for quick probes that reduce uncertainty without rewriting the app. Good probes are small: one targeted log line around the failing boundary (inputs, outputs, key state), a debug flag for a single component, a way to force deterministic behavior (fixed random seed, fixed time, single worker), a tiny seed dataset that triggers the issue, or a single failing request/response pair to replay.

Example: a signup flow fails “sometimes.” Claude might suggest logging the generated user ID, email normalization result, and unique constraint error details, then rerunning the same payload 10 times. If the failure only happens on the first run after deploy, that’s a strong hint to check migrations, cache warmup, or missing seed data.

Step 2 - Minimize to a small, repeatable test case

Create a repro-ready app

Spin up a React app and iterate on failing scenarios without heavy setup.

A good reproduction is useful. A minimal reproduction is powerful. It makes the bug faster to understand, easier to debug, and less likely to “fix” by accident.

Strip away anything that isn’t required. If the bug shows up after a long UI flow, find the shortest path that still triggers it. Remove optional screens, feature flags, and unrelated integrations until the bug either disappears (you removed something essential) or stays (you found noise).

Then shrink the data. If the bug needs a large payload, try the smallest payload that still breaks. If it needs a list of 500 items, see whether 5 fails, then 2, then 1. Remove fields one by one. The goal is the fewest moving parts that still reproduce the bug.

A practical method is “remove half and retest”:

- Cut the steps in half and check if the bug still happens.

- If yes, keep the remaining half and cut again.

- If no, restore half of what you removed and cut again.

- Repeat until you can’t remove anything without losing the bug.

Example: a checkout page crashes “sometimes” when applying a coupon. You discover it only fails when the cart has at least one discounted item, the coupon has lowercase letters, and shipping is set to “pickup.” That’s your minimal case: one discounted item, one lowercase coupon, one pickup option.

Once the minimal case is clear, ask Claude to turn it into a tiny reproduction scaffold: a minimal test that calls the failing function with the smallest inputs, a short script that hits one endpoint with a reduced payload, or a small UI test that visits one route and performs one action.

Step 3 - Identify likely root causes (with evidence)

Once you can reproduce the problem and you have a small test case, stop guessing. Your goal is to land on a short list of plausible causes, then prove or disprove each one.

A useful rule is to keep it to three hypotheses. If you have more than that, your test case is probably still too big or your observations are too vague.

Map symptoms to components

Translate what you see into where it could be happening. A UI symptom doesn’t always mean a UI bug.

Example: a React page shows a “Saved” toast, but the record is missing later. That can point to (1) UI state, (2) API behavior, or (3) the database write path.

Build evidence for each hypothesis

Ask Claude to explain likely failure modes in plain language, then ask what proof would confirm each one. The goal is to turn “maybe” into “check this exact thing.”

Three common hypotheses and the evidence to collect:

- UI/state mismatch: the client updates local state before the server confirms. Proof: capture a state snapshot before and after the action, and compare it to the actual API response.

- API edge case: the handler returns 200 but silently drops work (validation, ID parsing, feature flag). Proof: add request/response logs with correlation IDs, and verify the handler reaches the write call with the expected inputs.

- Database or timing issue: a transaction rolls back, a conflict error happens, or “read after write” is served from a cache/replica. Proof: inspect the DB query, rows affected, and error codes; log transaction boundaries and retry behavior.

Keep your notes tight: symptom, hypothesis, evidence, verdict. When one hypothesis matches the facts, you’re ready to lock in a regression test and fix only what’s necessary.

Step 4 - Add a regression test that fails for the right reason

A good regression test is your safety belt. It proves the bug exists, and it tells you when you’ve truly fixed it.

Start by choosing the smallest test that matches the real failure. If the bug only appears when multiple parts work together, a unit test can miss it.

Pick the test level that matches the bug

Use a unit test when a single function returns the wrong value. Use an integration test when the boundary between parts is the problem (API handler plus database, or UI plus state). Use end-to-end only when the bug depends on the full user flow.

Before you ask Claude to write anything, restate the minimized case as a strict expected behavior. Example: “When the user saves an empty title, the API must return 400 with message ‘title required’.” Now the test has a clear target.

Then have Claude draft a failing test first. Keep setup minimal and copy only the data that triggers the bug. Name the test after what the user experiences, not the internal function.

Verify the draft (don’t trust it blindly)

Do a quick pass yourself:

- Confirm it fails on the current code for the intended reason (not a missing fixture or wrong import).

- Check assertions are specific (exact status code, message, rendered text).

- Ensure the test covers one bug, not a bundle of behaviors.

- Keep the name user-focused, like “rejects empty title on save” rather than “handles validation.”

Once the test fails for the right reason, you’re ready to implement a narrow fix with confidence.

Step 5 - Implement a narrow fix

Plan the fix first

Outline hypotheses, tests, and validation checks before you touch code.

Once you have a small repro and a failing regression test, resist the urge to “clean things up.” The goal is to stop the bug with the smallest change that makes the test pass for the right reason.

A good narrow fix changes the smallest surface area possible. If the failure is in one function, fix that function, not the whole module. If a boundary check is missing, add the check at the boundary, not across the entire call chain.

If you’re using Claude to help, ask for two fix options, then compare them for scope and risk. Example: if a React form crashes when a field is empty, you might get:

- Option A: Add a guard in the submit handler that blocks empty input and shows an error.

- Option B: Refactor state handling so the field can never be empty.

Option A is usually the triage choice: smaller, easier to review, and less likely to break something else.

To keep the fix narrow, touch as few files as possible, prefer local fixes over refactors, add guards and validation where the bad value enters, and keep the behavior change explicit with one clear before/after. Leave comments only when the reason isn’t obvious.

Concrete example: a Go API endpoint panics when an optional query param is missing. The narrow fix is to handle the empty string at the handler boundary (parse with a default, or return a 400 with a clear message). Avoid changing shared parsing utilities unless the regression test proves the bug is in that shared code.

After the change, rerun the failing test and one or two nearby tests. If your fix requires updating many unrelated tests, it’s a signal the change is too broad.

Step 6 - Validate the fix with clear checks

Validation is where you catch the small, easy-to-miss problems: a fix that passes one test but breaks a nearby path, changes an error message, or adds a slow query.

First, rerun the regression test you added. If it passes, run the nearest neighbors: tests in the same file, the same module, and anything that covers the same inputs. Bugs often hide in shared helpers, parsing, boundary checks, or caching, so the most relevant failures usually show up close by.

Then do a quick manual check using the original report steps. Keep it short and specific: the same environment, the same data, the same sequence of clicks or API calls. If the report was vague, test the exact scenario you used to reproduce it.

A simple validation checklist

- Regression test passes, plus related tests in the same area.

- Manual repro steps no longer trigger the bug.

- Error handling still makes sense (messages, status codes, retries).

- Edge cases still behave (empty input, max sizes, unusual characters).

- No obvious performance hit (extra loops, extra calls, slow queries).

If you want help staying focused, ask Claude for a short validation plan based on your change and the failing scenario. Share what file you changed, what behavior you intended, and what could plausibly be affected. The best plans are short and executable: 5 to 8 checks you can finish in minutes, each with a clear pass/fail.

Finally, capture what you validated in the PR or notes: which tests you ran, what manual steps you tried, and any limits (for example, “did not test mobile”). This makes the fix easier to trust and easier to revisit later.

Common mistakes and traps (and how to avoid them)

Debug safely with snapshots

Experiment freely, then roll back quickly if a fix goes sideways.

The fastest way to waste time is to accept a “fix” before you can reproduce the problem on demand. If you can’t make it fail reliably, you can’t know what actually improved.

A practical rule: don’t ask for fixes until you can describe a repeatable setup (exact steps, inputs, environment, and what “wrong” looks like). If the report is vague, spend your first minutes turning it into a checklist you can run twice and get the same result.

Traps that slow you down

Fixing without a reproducible case. Require a minimal “fails every time” script or set of steps. If it only fails “sometimes,” capture timing, data size, feature flags, and logs until it stops being random.

Minimizing too early. If you strip the case down before you’ve confirmed the original failure, you can lose the signal. First lock the baseline reproduction, then shrink it one change at a time.

Letting Claude guess. Claude can propose likely causes, but you still need evidence. Ask for 2 to 3 hypotheses and the exact observations that would confirm or reject each one (a log line, a breakpoint, a query result).

Regression tests that pass for the wrong reason. A test can “pass” because it never hits the failing path. Make sure it fails before the fix, and that it fails with the expected message or assertion.

Treating symptoms instead of the trigger. If you add a null check but the real issue is “this value should never be null,” you may hide a deeper bug. Prefer fixing the condition that creates the bad state.

A quick sanity check before you call it done

Run the new regression test and the original reproduction steps before and after your change. If a checkout bug only happens when a promo code is applied after changing shipping, keep that full sequence as your “truth,” even if your minimized test is smaller.

If your validation depends on “it looks good now,” add one concrete check (a log, a metric, or a specific output) so the next person can verify it quickly.

A quick checklist, prompt templates, and next steps

When you’re under time pressure, a small, repeatable loop beats heroic debugging.

One-page triage checklist

- Reproduce: get a reliable repro and note exact inputs, environment, and expected vs actual.

- Minimize: reduce to the smallest steps or test that still fails.

- Explain: list 2 to 3 likely root causes and the evidence for each.

- Lock it in: add a regression test that fails for the right reason.

- Fix + validate: make the narrowest change, then run a short validation checklist.

Write the final decision in a few lines so the next person (often future you) can trust it. A useful format is: “Root cause: X. Trigger: Y. Fix: Z. Why safe: W. What we did not change: Q.”

Prompt templates you can paste

- “Given this bug report and logs, ask me only the missing questions needed to reproduce it reliably.”

- “Help me minimize: propose a smaller test case and tell me what to remove first, one change at a time.”

- “Rank likely root causes and cite the exact files, functions, or conditions that support each claim.”

- “Write a regression test that fails only because of this bug. Explain why it fails for the right reason.”

- “Suggest the narrowest fix, plus a validation checklist (unit, integration, and manual checks) that proves we didn’t break nearby behavior.”

Next steps: automate what you can (a saved repro script, a standard test command, a template for root-cause notes).

If you build apps with Koder.ai (koder.ai), Planning Mode can help you outline the change before you touch code, and snapshots/rollback make it easier to experiment safely while you work through a tricky repro. Once the fix is validated, you can export the source code or deploy and host the updated app, including with a custom domain when needed.

FAQ

What is bug triage, in plain terms?

Bug triage is the habit of turning a vague report into a clear, testable statement, then making the smallest change that proves the statement is no longer true.

It’s less about "fix everything" and more about reducing uncertainty step by step: reproduce, minimize, form evidence-based hypotheses, add a regression test, fix narrowly, validate.

Why does the reproduce → minimize → test → fix loop matter so much?

Because each step removes a different kind of guesswork.

- Reproduce: proves it’s real and repeatable

- Minimize: removes noise so you stop chasing unrelated behavior

- Hypothesize with evidence: keeps you from fixing the wrong thing

- Regression test: proves the bug existed and stays fixed

- Narrow fix + validation: reduces side effects and re-breaks

How do I turn a messy bug report into something actionable?

Rewrite it as: “When I do X, I expect Y, but I get Z.”

Then collect just enough context to make it testable:

- version/commit + where it happens (local/staging/prod)

- environment (device, OS, browser, flags, region)

- exact inputs/actions

- who is affected (everyone, a role, one tenant)

- evidence (timestamps, error text, request/trace IDs, logs)

What should I do first if I can’t reproduce the bug?

Start by confirming you can reproduce it in the smallest environment that can still show it (often local dev with a tiny dataset).

If it’s “sometimes,” try to make it deterministic by controlling variables:

- rerun the same payload 10 times

- fix time/randomness if possible

- reduce concurrency (single worker/thread)

- add one targeted log at the boundary that likely fails

Don’t move on until you can make it fail on demand, or you’re just guessing.

How do I minimize a bug to a small test case?

Minimization means removing anything that isn’t required while keeping the bug.

A practical method is “remove half and retest”:

- cut steps/data in half

- if it still fails, cut again

- if it stops failing, restore half and cut differently

Shrink both steps (shorter user flow) and data (smaller payload, fewer fields/items) until you have the smallest repeatable trigger.

How can Claude Code help without turning into guesswork?

Use Claude Code to speed up analysis, not to replace verification.

Good requests look like:

- “Here are repro steps + logs. List 2–3 hypotheses and what evidence would confirm each.”

- “Given this diff and stack trace, where are the most likely failure boundaries?”

- “Draft a minimal failing test for this exact scenario.”

Then you validate: reproduce locally, check logs/traces, and confirm any test fails for the right reason.

How many root-cause hypotheses should I consider at once?

Keep it to three. More than that usually means your repro is still too big or your observations are vague.

For each hypothesis, write:

- symptom (what you observe)

- hypothesis (what could cause it)

- evidence to collect (one log line, one breakpoint, one query result)

- verdict (supported/rejected)

This forces progress and prevents endless “maybe it’s X” debugging.

What makes a good regression test for a bug?

Pick the smallest test level that matches the failure:

- Unit test: one function returns the wrong thing

- Integration test: boundary issues (handler + DB, client + API)

- End-to-end: only if the full flow is required

A good regression test:

- fails on current code for the intended reason

- asserts something specific (status code, message, rendered text)

- covers one bug, not a bundle of behaviors

How do I keep a fix narrow and low-risk?

Make the smallest change that makes the failing regression test pass.

Rules of thumb:

- touch as few files as possible

- fix at the boundary where the bad value enters

- prefer a guard/validation over a refactor during triage

- avoid “cleanup” unless the test proves it’s necessary

If your fix forces lots of unrelated test updates, it’s probably too broad.

How do I validate the fix so the bug doesn’t come back?

Use a short checklist you can execute quickly:

- regression test passes

- a few neighboring tests pass (same module/inputs)

- original manual repro steps no longer trigger the bug

- error handling still makes sense (messages, status codes)

- quick edge cases (empty input, max size, weird characters)

- no obvious performance regressions

Write down what you ran and what you didn’t test so the result is trustworthy.