Apr 28, 2025·7 min

Build a Simple To‑Do App Step by Step (Plain English)

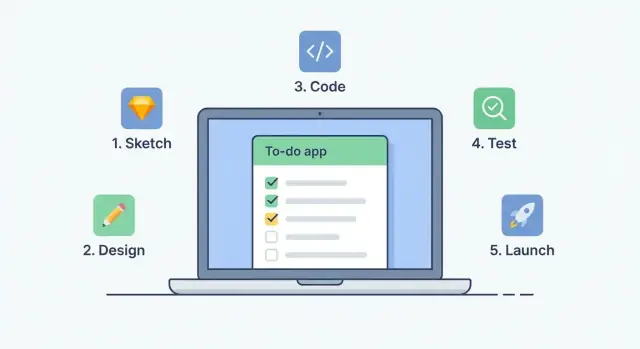

A clear, step-by-step guide to building a small to-do app: plan the features, create the screens, add logic, save data, test, and publish.

What We’re Building (and What You’ll Learn)

When I say “app” in this guide, I mean a small web app: a single page you open in a browser that responds to what you click and type. No installs, no accounts, no heavy setup—just a simple project you can run locally.

The goal (what the finished app will do)

By the end, you’ll have a to‑do app that can:

- Add tasks from an input box

- Mark tasks as done (so you can see what’s completed)

- Delete tasks you no longer need

- Keep tasks after refresh using

localStorage(so closing the tab doesn’t wipe everything)

It won’t be perfect or “enterprise-grade,” and that’s the point. This is a beginner project designed to teach the basics without throwing lots of tools at you.

What you’ll learn (in plain language)

You’ll build the app step by step and pick up the core pieces of how front-end web apps work:

- HTML to create the page structure (input, button, list)

- CSS to make it readable and pleasant to use

- JavaScript to handle clicks, create list items, and update the page

- localStorage to save and load tasks so they stick around

- Basic testing and debugging (spotting small mistakes and fixing them)

What you need before we start

Keep it simple. You only need:

- A computer (Windows, Mac, or Linux)

- A modern browser (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Edge)

- A code editor (VS Code is popular, but any editor works)

If you can create a folder and edit a few files, you’re ready.

Step 1: Decide the App’s Goal and Features

Before you write any code, decide what “success” looks like. This tutorial builds one small app with one clear job: help you track tasks you want to do.

Pick the app’s one job

Write a one-sentence goal you can keep in front of you while building:

“This app lets me add tasks to a list so I don’t forget them.”

That’s it. If you feel tempted to add calendars, reminders, tags, or accounts, park those ideas for later.

Must-have vs. nice-to-have

Make two quick lists:

Must-have (for this project):

- Add a task (type text, click a button)

- See tasks in a list

- Mark a task as done

- Delete a task

- Keep tasks after refresh (we’ll use localStorage later)

Nice-to-have (not required today): due dates, priorities, categories, search, drag-and-drop, cloud sync.

Keeping “must-have” small helps you actually finish.

Describe the screen in plain words

This app can be a single page with:

- One text input (“Add a task…”) and an “Add” button

- A list of tasks underneath

- Each task has a “done” toggle and a “delete” button

Define what “done” means

Be specific so you don’t get stuck:

- “Done” = the task looks crossed out (or faded), and it stays in the list until you delete it.

With that decided, you’re ready to set up the project files.

Step 2: Set Up Your Project Files

Before we write any code, let’s create a clean little “home” for the app. Keeping files organized from the start makes the next steps smoother.

1) Create a project folder

Make a new folder on your computer and name it something like todo-app. This folder will hold everything for this project.

Inside that folder, create three files:

index.html(the page structure)styles.css(the look and layout)app.js(the behavior and interactivity)

If your computer hides file extensions (like “.html”), make sure you’re actually creating real files. A common beginner mistake is ending up with index.html.txt.

2) Open the folder in your editor and browser

Open the todo-app folder in your code editor (VS Code, Sublime Text, etc.). Then open index.html in your web browser.

At this point, your page may be blank—and that’s fine. We’ll add content in the next step.

3) How you’ll see changes

When you edit your files, your browser won’t automatically update (unless you use a tool that does that).

So the basic loop is:

- Save your file in the editor

- Go to the browser tab

- Refresh the page to see the update

If something “doesn’t work,” refresh is the first thing to try.

Optional: Use a simple local server (nice, not required)

You can build this app by double‑clicking index.html, but a local server can prevent weird issues later (especially when you start saving data or loading files).

Beginner-friendly options:

- In VS Code, install Live Server and click “Go Live”

- If you already have Python installed, run this inside the folder:

python -m http.server

Then open the address it prints (often http://localhost:8000) in your browser.

Step 3: Build the Page Structure (HTML)

Now we’ll create a clean skeleton for the app. This HTML won’t make anything interactive yet (that’s next), but it gives your JavaScript clear places to read from and write to.

The minimal layout we need

We’ll include:

- A title so the page is obvious at a glance

- An input box for the task text

- An Add button to submit a task

- A list area where new tasks will appear

Keep the names simple and readable. Good IDs/classes make later steps easier because your JavaScript can grab elements by name without confusion.

Paste this into your index.html

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<title>To‑Do App</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />

</head>

<body>

<main class="app" id="app">

<h1 class="app__title" id="appTitle">My To‑Do List</h1>

<form class="task-form" id="taskForm">

<label class="task-form__label" for="taskInput">New task</label>

<div class="task-form__row">

<input

id="taskInput"

class="task-form__input"

type="text"

placeholder="e.g., Buy milk"

autocomplete="off"

/>

<button id="addButton" class="task-form__button" type="submit">

Add

</button>

</div>

</form>

<ul class="task-list" id="taskList" aria-label="Task list"></ul>

</main>

<script src="app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

That’s it for structure. Notice we used id="taskInput" and id="taskList"—those are the two elements you’ll talk to most in JavaScript.

Step 4: Make It Look Clean (CSS)

Right now your page exists, but it probably looks like a plain document. A little CSS makes it easier to use: clearer spacing, readable text, and buttons that feel clickable.

Start with a simple centered container

A centered box keeps the app focused and stops the content from stretching across a wide screen.

/* Basic page setup */

body {

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

background: #f6f7fb;

margin: 0;

padding: 24px;

}

/* Centered app container */

.container {

max-width: 520px;

margin: 0 auto;

background: #ffffff;

padding: 16px;

border-radius: 10px;

box-shadow: 0 6px 18px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.08);

}

Make tasks easy to scan

Each task should look like a separate “row,” with comfortable spacing.

ul { list-style: none; padding: 0; margin: 16px 0 0; }

li {

display: flex;

align-items: center;

justify-content: space-between;

gap: 12px;

padding: 10px 12px;

border: 1px solid #e7e7ee;

border-radius: 8px;

margin-bottom: 10px;

}

.task-text { flex: 1; }

Add a clear “done” look

When a task is completed, it should visually change so you can tell at a glance.

.done .task-text {

text-decoration: line-through;

color: #777;

opacity: 0.85;

}

Make buttons consistent

Keep buttons the same size and style so they feel like part of one app.

button {

border: none;

border-radius: 8px;

padding: 8px 10px;

cursor: pointer;

}

button:hover { filter: brightness(0.95); }

That’s enough styling for a clean, friendly UI—no advanced tricks needed. Next, we’ll wire up behavior with JavaScript.

Step 5: Add Tasks (JavaScript Basics)

Go beyond localStorage

Turn your to-do app into a real React project with a backend using chat.

Now that you have the input, button, and list on the page, you’ll make them do something. The goal is simple: when someone types a task and hits Add (or presses Enter), a new item appears in the list.

Wire up the button and the Enter key

In your JavaScript file, first grab the elements you need, then listen for two actions: a button click and the Enter key inside the input.

const taskInput = document.querySelector('#taskInput');

const addBtn = document.querySelector('#addBtn');

const taskList = document.querySelector('#taskList');

function addTask() {

const text = taskInput.value.trim();

// Block empty tasks (including ones that are just spaces)

if (text === '') return;

const li = document.createElement('li');

li.textContent = text;

taskList.appendChild(li);

// Clear the input and put the cursor back

taskInput.value = '';

taskInput.focus();

}

addBtn.addEventListener('click', addTask);

taskInput.addEventListener('keydown', (event) => {

if (event.key === 'Enter') {

addTask();

}

});

What this does (in plain English)

- Reads the text from the input and uses

trim()to remove extra spaces at the start/end. - Stops if the task is empty, so you don’t add blank items.

- Creates a new

<li>, sets its text, and adds it to the list. - Resets the input and returns focus to it so the next task is quick to type.

If nothing happens, double-check your element IDs in the HTML match your JavaScript selectors exactly (this is one of the most common beginner hiccups).

Step 6: Mark Done and Delete Tasks

Now that you can add tasks, let’s make them actionable: you should be able to mark a task as done and remove it.

Store tasks as simple data

Instead of storing tasks as plain strings, store them as objects. That gives each task a stable identity and a place to track “done” status:

text: what the task saysdone:trueorfalseid: a unique number so we can find/delete the right task

Here’s a simple example:

let tasks = [

{ id: 1, text: "Buy milk", done: false },

{ id: 2, text: "Email Sam", done: true }

];

Add a Done control and a Delete button

When you render each task on the page, include either a checkbox or a “Done” button, plus a “Delete” button.

An event listener is just “a way to react to clicks.” You attach it to a button (or the whole list), and when the user clicks, your code runs.

A beginner-friendly pattern is event delegation: put one click listener on the task list container, then check what was clicked.

function toggleDone(id) {

tasks = tasks.map(t => t.id === id ? { ...t, done: !t.done } : t);

renderTasks();

}

function deleteTask(id) {

tasks = tasks.filter(t => t.id !== id);

renderTasks();

}

document.querySelector("#taskList").addEventListener("click", (e) => {

const id = Number(e.target.dataset.id);

if (e.target.matches(".toggle")) toggleDone(id);

if (e.target.matches(".delete")) deleteTask(id);

});

In your renderTasks() function:

- Add

data-id="${task.id}"to each button. - Visually show done tasks (for example, by adding a

.doneclass).

Step 7: Save Tasks So They Stay (localStorage)

Right now your to‑do list has an annoying problem: if you refresh the page (or close the tab), everything disappears.

That happens because your tasks only exist in JavaScript memory. When the page reloads, that memory resets.

localStorage = a tiny “save box” inside the browser

localStorage is built into the browser. Think of it like a small box where you can store text under a name (a “key”). It’s perfect for beginner projects because it doesn’t need a server or account system.

We’ll store the entire task list as JSON text, then load it back when the page opens.

1) Save after every change

Any time you add a task, mark one done, or delete one, call saveTasks().

const STORAGE_KEY = "todo.tasks";

function saveTasks(tasks) {

localStorage.setItem(STORAGE_KEY, JSON.stringify(tasks));

}

Wherever your app updates the tasks array, do this right after:

saveTasks(tasks);

renderTasks(tasks);

2) Load on page start (and render)

When the page loads, read the saved value. If there’s nothing saved yet, fall back to an empty list.

function loadTasks() {

const saved = localStorage.getItem(STORAGE_KEY);

return saved ? JSON.parse(saved) : [];

}

let tasks = loadTasks();

renderTasks(tasks);

That’s it: your app now remembers tasks across refreshes.

Tip: localStorage only stores strings, so JSON.stringify() turns your array into text, and JSON.parse() turns it back into a real array when you load it.

Step 8: Test and Fix Common Bugs

Publish without setup pain

Host your app from Koder.ai when you are ready to share it publicly.

Testing sounds boring, but it’s the fastest way to turn your to‑do app from “works on my machine” into “works every time.” Do one quick pass after each small change.

A quick test pass (60 seconds)

Run through the main flow in this order:

- Add a task

- Mark it done

- Delete it

- Refresh the page (to confirm the UI still behaves as expected)

If any step fails, fix it before adding new features. Small apps get messy when you stack problems.

Try edge cases that break beginner apps

Edge cases are inputs that you didn’t design for, but real people will do anyway:

- Very long text (does it overflow or push buttons off screen?)

- Repeated tasks (do you delete the right one?)

- Blank input (does it add an empty task?)

A common fix is to block empty tasks:

const text = input.value.trim();

addButton.disabled = text === "";

(You can run that on every input event, and again right before you add.)

Fast “nothing happens” checklist

When clicks do nothing, it’s usually one of these:

- A selector doesn’t match (an

idor class name differs between HTML and JS). - Your script isn’t loaded (wrong filename/path, or

app.jsnot found). - There’s a JavaScript error stopping the rest of the file.

Use the console to find what’s really happening

When something feels random, log it:

console.log("Adding:", text);

console.log("Current tasks:", tasks);

Check the browser’s Console for errors (red text). Once you’ve fixed the issue, remove the logs so they don’t clutter your project.

Step 9: Make It Friendly to Use (Accessibility + Mobile)

A to‑do app is only “done” when it’s comfortable for real people to use—on phones, with a keyboard, and with assistive tools like screen readers.

Make it easy to tap on mobile

On small screens, tiny buttons are frustrating. Give clickable things enough space:

- Use larger padding on buttons (aim for about 44px tall).

- Add spacing between the Done and Delete buttons so you don’t mis-tap.

- Keep your input field full-width on mobile so typing feels natural.

If you’re using CSS, increasing padding, font-size, and gap often makes the biggest difference.

Add labels and ARIA (what and why)

Screen readers need clear names for controls.

- Your text input should have a real

<label>(best option). If you don’t want to show it, you can visually hide it with CSS, but keep it in the HTML. - Icon-only buttons (like a trash can) should include

aria-label="Delete task"so the screen reader doesn’t announce it as “button” with no context.

This helps people understand what each control does without guessing.

Keyboard support: Tab + Enter

Make sure you can use the whole app without a mouse:

- You should be able to Tab to the input and buttons.

- Pressing Enter in the input should add the task (use a

<form>so Enter works naturally). - When a task is added, consider moving focus back to the input so adding multiple tasks is quick.

Readability: contrast and font size

Use a readable font size (16px is a good baseline) and strong color contrast (dark text on a light background, or the reverse). Avoid using color alone to show “done”—add a clear style like a strikethrough plus a “Done” state.

Step 10: Clean Up and Organize Your Code

Build while earning

Create content about Koder.ai or invite others and get credits for building.

Now that everything works, take 10–15 minutes to tidy up. This makes future fixes easier and helps you understand your own project when you come back later.

A simple folder structure

Keep it small and predictable:

/index.html— the page structure (input, button, list)/styles.css— how the app looks (spacing, fonts, “done” style)/app.js— the behavior (add, toggle done, delete, save/load)/README.md— quick notes for “future you”

If you prefer subfolders, you can also do:

/css/styles.css/js/app.js

Just make sure your <link> and <script> paths match.

Make the JavaScript easier to read

A few quick wins:

- Use clear names:

taskInput,taskList,saveTasks() - Keep functions small: one function should do one job

- Use short comments only where the code isn’t obvious (avoid commenting every line)

For example, it’s easier to scan:

renderTasks(tasks)addTask(text)toggleTask(id)deleteTask(id)

Add a tiny README

Your README.md can be simple:

- What it does (a to-do list that saves tasks)

- How to run it (open

index.htmlin a browser) - Optional: any known limitations

Back up your project

At minimum, zip the folder after you finish a milestone (like “localStorage works”). If you want version history, Git is great—but optional. Even one backup copy can save you from accidental deletions.

Step 11: Publish Your App and Share It

Publishing just means putting your app’s files (HTML, CSS, JavaScript) somewhere public on the internet so other people can open a link and use it. Since this to‑do app is a “static site” (it runs in the browser and doesn’t need a server), you can host it for free on several services.

Option 1: GitHub Pages (great for static sites)

High-level steps:

- Create a GitHub account (if you don’t have one).

- Make a new repository (project) and upload your files (or push with Git).

- In the repo, go to Settings → Pages.

- Choose the branch to publish (often main) and the folder (often / root).

- Save—GitHub will give you a public URL.

If your app uses separate files, double-check your file names match your links exactly (for example styles.css vs style.css).

Option 2: Netlify or Vercel (easy drag-and-drop)

If you want the simplest “upload and go” approach:

- Create an account on Netlify or Vercel.

- Look for Deploy / Add New Project.

- Drag and drop your project folder (or connect a GitHub repo).

- Wait for the build/upload to finish.

- Open the generated URL and test it.

Quick checklist before you share the link

- Refresh the page: your tasks should still be there (

localStorageworking). - Try adding, completing, and deleting tasks: no broken buttons.

- Open it on mobile (or narrow your browser window): nothing spills off the screen.

Once it passes, send the link to a friend and ask them to try it—fresh eyes catch issues fast.

Next Steps: Easy Upgrades You Can Try

You’ve built a working to‑do app. If you want to keep learning without jumping to a huge project, these upgrades add real value and teach useful patterns.

1) Edit task text

Add an “Edit” button next to each task. When clicked, swap the task label for a small input field (pre-filled), plus “Save” and “Cancel.”

Tip: keep your task data as an array of objects (with an id and text). Editing then becomes: find the right task by id, update text, re-render, and save.

2) Filters: All / Active / Done

Add three buttons at the top: All, Active, Done.

Store the current filter in a variable like currentFilter = 'all'. When rendering, show:

- All: every task

- Active: tasks not completed

- Done: completed tasks

3) Due dates or simple categories

Keep it lightweight:

- Add an optional due date (

YYYY-MM-DD) and display it next to the task - Or add a category like “Work / Home / School” using a small dropdown

Even one extra field teaches you how to update your data model and UI together.

4) Later: move from localStorage to a simple backend

When you’re ready, the big idea is: instead of saving to localStorage, you send tasks to an API (a server) using fetch(). The server stores them in a database, so tasks sync across devices.

If you want to try that jump without rebuilding everything from scratch, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you prototype the “next version” quickly: describe the features in chat (API endpoints, database tables, UI changes), iterate in planning mode, and still export the source code when you’re ready to learn from (or customize) the generated React/Go/PostgreSQL project.

5) A good next beginner project

Try building a notes app (with search) or a habit tracker (daily check-ins). They reuse the same skills: list rendering, editing, saving, and simple UI design.