Nov 15, 2025·8 min

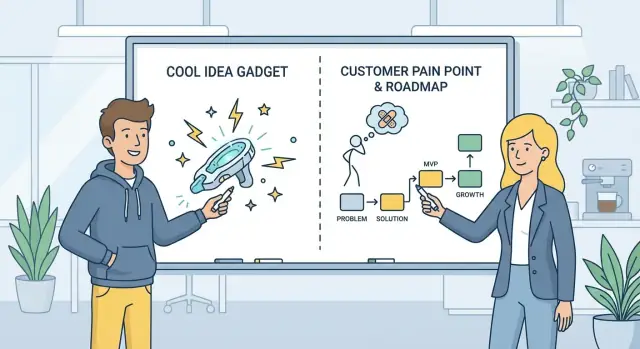

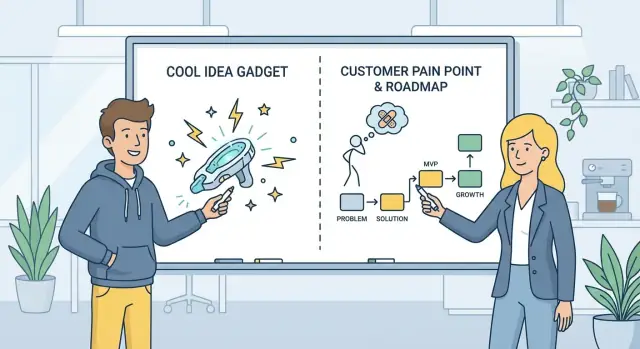

Build a Startup Around Painful Problems, Not Cool Ideas

Learn how to build a startup by starting with painful problems, not shiny ideas. Find real demand, validate quickly, and win with clear value.

Learn how to build a startup by starting with painful problems, not shiny ideas. Find real demand, validate quickly, and win with clear value.

A painful problem is something people already feel in their day-to-day life or work—something that reliably costs them time, money, revenue, sleep, reputation, or compliance risk. They’re not “interested” in fixing it; they’re already trying to reduce it, even if their current solution is messy (spreadsheets, manual workarounds, hiring temps, or just enduring it).

A cool idea is the opposite: it’s novel, clever, or exciting—but it isn’t tied to a strong, frequent, costly problem. People might say it’s “neat” or “I’d use that,” but they aren’t changing behavior or allocating budget to get it.

Pain creates urgency. If the problem is expensive or risky enough, people pay attention quickly: they reply to your emails, take meetings, and trial alternatives. Pain also creates budget: companies fund problems that threaten revenue, burn payroll hours, or increase exposure. Individuals spend on problems that save time, reduce stress, or prevent something worse.

Cool ideas usually compete with “maybe later.” When there’s no immediate consequence for ignoring it, it loses to everything else on the priority list.

This guide follows a repeatable path:

You’re not here to bet months on a big build. You’ll run small tests—short conversations, lightweight prototypes, pre-sales, and narrow MVPs—to prove there’s a painful problem with real willingness to pay. If the pain isn’t there, you’ll know early and can pivot, narrow, or walk away without regret.

A “cool idea” is easy to love and hard to sell. It gets compliments, upvotes, and “you should totally build this” energy—but that admiration doesn’t translate into a problem-first startup with real willingness to pay.

When an idea isn’t tied to a sharp startup pain point, the same symptoms appear repeatedly:

Mild pain creates infinite procrastination. If your product helps with something that’s “annoying” rather than “costly,” buyers postpone forever: “Let’s revisit next quarter.” That’s deadly for go-to-market basics, because urgency is what turns conversations into decisions.

This is why customer discovery should focus less on what people like and more on what they’ve already tried to fix—especially where time, money, or reputation is at stake. In jobs-to-be-done terms: what job is failing, and what’s the cost of failure?

Novel features can temporarily mask weak demand. Early users may play with it, share it, and praise the design—while refusing to integrate it into workflows or pay for it. Novelty boosts attention, not commitment.

The goal when you validate a startup idea isn’t admiration. It’s measurable relief: shorter cycle times, fewer errors, less manual work, lower risk, faster revenue. If you can’t name the relief and measure it, your MVP based on pain will struggle to earn adoption.

Cool ideas feel exciting, but painful problems have gravity. To stay honest, use a quick “pain score” before you fall in love with a solution.

Give each dimension a 1–5 score, then multiply.

A problem that’s weekly (4), blocks work (5), and costs $2k/month (4) scores 80. A rare, mild annoyance usually can’t compete.

Write down three roles:

High pain with no clear buyer often turns into “everyone agrees, nobody pays.” The best opportunities have the pain and budget aligned—or a strong internal champion who can translate user pain into a business case.

Pain becomes urgent when there’s a clock attached:

If a customer says “we’ll deal with it next quarter,” your pain score is probably inflated.

Workarounds are evidence someone is already paying—just not with your product yet. Watch for:

The more effort people spend to avoid the problem, the more likely they’ll pay for relief.

A painful problem only turns into a business when it belongs to a real someone, in a real situation, with real constraints (time, budget, tools, approvals). “Small businesses” or “creators” is too broad—pain gets diluted, and your learning slows to a crawl.

Picking a specific customer and setting lets you:

When you start broad, every conversation sounds different, and you end up building a flexible product that fits nobody well.

Look for places where people complain with urgency and detail—especially where the same issue keeps showing up:

Concentrated pain looks like repeated scenarios, strong emotions (“this is killing us”), and people already spending time or money to patch the issue.

Use this to define your first target customer:

If you can’t fill in “where to reach them this week,” the audience is still too vague.

Customer discovery isn’t about asking people whether your idea is “good.” It’s about uncovering what they already do today to deal with a painful situation—and what it costs them.

Opinion questions (“Would you use…?” “Do you like…?”) produce polite, inaccurate answers. Behavior questions surface reality.

Try prompts like:

Cut through vague answers by asking for a specific, recent incident:

If they can’t recall a recent example, the pain may be occasional—or not important.

Pain is measurable. During the story, listen for (and ask about) costs:

Avoid describing your solution or asking for validation. Collect multiple stories, then look for repeated triggers, workarounds, and consequences.

A useful close: “If you could wave a magic wand and change one thing about this process, what would it be—and why?”

After a handful of customer conversations, you’ll have pages of quotes and anecdotes. The goal now is to turn that mess into a clear, ranked set of problems—so you don’t build around the most entertaining story instead of the most painful one.

Extract problems, not feature requests. Highlight moments where the person describes friction, delay, risk, embarrassment, extra work, or lost money. Group similar moments under one problem label.

Create a simple table with columns like: Problem, Who said it, Frequency, Severity, Current workaround, Cost of workaround. Rank problems using a quick score (for example 1–5 for frequency and 1–5 for severity). Multiply them. You’ll quickly see what’s consistently painful.

Pay attention to exact phrases customers repeat: “I hate…”, “It always breaks when…”, “I’m stuck waiting for…”. Repeated language is a signal that the problem is top-of-mind.

Also look for repeated consequences—these are often stronger than complaints:

Write one sentence that forces clarity:

For [specific customer] in [specific setting], [problem] happens when [trigger], causing [painful consequence] because [root cause].

If you can’t fill in each bracket from real quotes, you’re not done.

Some problems will feel “bigger” or more fun. Ignore anything that:

What remains is your best candidate for a problem worth solving.

Validation isn’t “Do people like this?” It’s “Will someone commit time, reputation, or money to get this fixed?” Before you write code, look for concrete proof that the pain is strong enough to trigger action.

The best signals involve commitment:

Create a simple landing page with one specific offer: who it’s for, the painful situation, the promised outcome, and a clear call to action (book a call, join a pilot, place a deposit). Then do targeted outreach to people who fit the exact context.

Your goal isn’t traffic. Your goal is conversations with qualified buyers. A dozen high-quality outreaches can beat a thousand random clicks.

Avoid “What would you pay?” Instead, anchor pricing to current alternatives:

Decide upfront what “pass” looks like: number of qualified calls booked, pilot commitments, deposit amount, or conversion rate from outreach to next step. If you can’t set a threshold, you’re not testing—you’re hoping.

An MVP isn’t a smaller version of your dream product. It’s the smallest way to produce a real, noticeable drop in the customer’s pain.

Start by writing the outcome in plain language:

Keep it measurable and immediate.

Examples:

That outcome becomes your MVP target. Everything else is optional.

If a feature doesn’t shorten time-to-relief, lower effort, or reduce risk, it’s not MVP. Early customers forgive rough edges when the pain drops quickly; they won’t forgive “nice-to-have” extras that delay relief.

A useful rule: ship the first version that can deliver the outcome at least once for a real customer, end-to-end.

To learn faster, replace software with humans where needed:

Manual work is not failure; it’s how you discover what must be automated later.

When speed matters, use tooling that lets you prototype the workflow and iterate in days, not weeks. For example, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be useful here: you can describe the workflow in chat, generate a working web app (often React on the front end with a Go + PostgreSQL backend under the hood), and then refine it as you learn from pilots. If the test works, you can export the source code and keep building; if it doesn’t, you’ve minimized sunk cost.

Features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback can also help you run controlled MVP experiments without turning every change into a risky rebuild.

Write this down and share it with early customers:

The goal is relief, proof of demand, and clarity on what to build next—not perfection.

Positioning is not “what the product does.” It’s a clear promise to a specific person in a specific situation: you have this painful problem, and we help you get this result. If your positioning sounds like a feature list, you’re forcing customers to do the translation work.

Use a simple structure and keep it concrete:

“For X, who struggle with Y, we provide Z outcome.”

Examples:

Notice the outcome is what they want, not what you built.

Customers don’t buy “better.” They buy less risk, less time, more money, fewer mistakes. Translate pain into results you can point to:

If you can’t measure it yet, pick a proxy (“fewer handoffs,” “one source of truth,” “same-day turnaround”) and refine after real usage.

Your best copy is often a direct quote from discovery calls. Keep a swipe file of exact phrases customers use (“I’m constantly chasing…”, “We’re blind until month-end…”).

Mirror those words:

Objections are usually comparisons to what they already do. List the true alternatives (spreadsheets, a general tool, an agency, “do nothing”) and answer them directly:

Strong positioning makes buying feel like relief, not a gamble.

Early go-to-market isn’t a growth hack. It’s a truth-finding mission. Your goal is to confirm (or disprove) that the pain is real, frequent, and expensive enough that people will change behavior and pay for relief.

Choose a channel that puts you in direct contact with buyers fast:

Don’t spread across five channels. One is enough until you can consistently book conversations.

Treat every pitch like an interview with a price tag. You’re testing:

If people won’t take the next step—trial, pilot, paid test—you’ve learned something important.

Keep it simple and measurable:

Watch where you leak. If calls convert to pilots but pilots don’t convert to paid, your MVP may not deliver relief fast enough—or you’re selling to the wrong buyer.

Every “no” should produce a reason. Capture it verbatim and tag it (timing, price, trust, missing feature, wrong persona, unclear value). Then feed it back into:

The point of early selling is not to win arguments—it’s to compress learning into weeks, not months.

A “cool idea” can get sign-ups. A painful problem gets people to change behavior, stick around, and pay. The goal of metrics here is simple: prove users are getting a real outcome—not just clicking around.

Early on, focus on signals that your product delivers relief quickly:

If activation is high but repeat usage is low, you may be solving a “nice-to-have” task, not an urgent pain.

Retention is the clearest proof that the problem is persistent.

Track cohort retention (week 1 → week 4, month 1 → month 3) and pair it with expansion signals:

When the pain is real, customers naturally widen usage because the product is tied to critical work.

Watch for users who log in but don’t finish the job:

This often means your value is unclear, the workflow is too hard, or the outcome isn’t compelling.

Churn and stalled trials are data. Run short interviews to learn:

Use those answers to refine your ICP and tighten the problem statement. If churn is random and reasons are vague, you’re likely not anchored to a specific painful problem yet.

Most early startup “failures” aren’t because the product is bad—they’re because the pain isn’t strong enough, or you’re solving it for the wrong buyer. The goal isn’t to persist forever; it’s to learn quickly and make a clean decision.

Pivot when you see consistent effort from you but inconsistent pull from customers. Common red flags:

If these patterns show up across multiple conversations, you’re likely not sitting on a painful problem—at least not in the way you framed it.

There are two different moves:

Don’t change both at once. Otherwise you won’t know what caused results to improve.

Even when outcomes are weak, preserve evidence: a message that got replies, a channel that produced qualified calls, or a use case where urgency spiked. Treat those as anchors while you test changes.

Set a time-boxed decision rule to avoid endless tweaking: for example, “In the next 3 weeks, run 15 discovery calls and try to close 3 paid pilots. If we can’t identify a budget owner and a repeatable trigger for urgency, we walk away.”

Walking away isn’t failure; it’s protecting your time for a problem that actually hurts.

A painful problem reliably costs someone time, money, revenue, reputation, sleep, or compliance risk, and they’re already trying to reduce it (even with messy workarounds).

A cool idea gets interest and compliments, but it doesn’t force action—so it competes with “maybe later.”

Pain creates urgency and budget. When a problem threatens revenue, wastes payroll hours, or increases risk, people:

Novelty can get attention, but urgency is what produces decisions.

Use a simple score: Frequency × Severity × Cost (each 1–5), then multiply.

If you can’t quantify at least one of these with real examples, you’re likely dealing with a nice-to-have.

Define three roles:

If users feel pain but there’s no clear buyer (or buying process), you risk “everyone agrees, nobody pays.” Aim for pain and budget alignment—or a strong internal champion who can build a business case.

Look for a clock that forces action, such as:

If the common response is “next quarter,” treat that as a warning that urgency (and willingness to pay) may be weak.

Workarounds are proof people are already paying—just not with your product. Examples include:

The more effort and coordination a workaround requires, the better your odds that relief is valuable enough to sell.

Ask about behavior and recent incidents, not opinions:

Avoid “Would you use…?” questions; they produce polite, unreliable answers.

Use commitment-based validation before building:

Interest without commitment is noise; commitment is evidence.

Define the smallest relieving outcome: “After using this, the customer no longer has to…” and make it measurable.

Then ship the smallest version that can deliver that outcome end-to-end at least once, even if it uses manual steps (concierge setup, done-with-you implementation, manual imports). Speed-to-relief beats feature completeness.

Pivot (or narrow) when you see consistent effort from you but inconsistent pull from customers:

Separate the moves:

Time-box tests (e.g., X calls, Y pilot attempts) so you don’t drift into endless tweaking.