Aug 26, 2025·8 min

How to Build AI-First Products with Models in App Logic

A practical guide to building AI-first products where the model drives decisions: architecture, prompts, tools, data, evaluation, safety, and monitoring.

What It Means to Build an AI-First Product

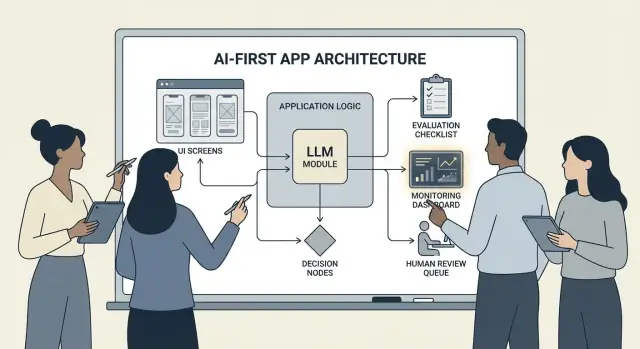

Building an AI-first product doesn’t mean “adding a chatbot.” It means the model is a real, working part of your application logic—the same way a rules engine, search index, or recommendation algorithm might be.

Your app isn’t just using AI; it’s designed around the fact that the model will interpret input, choose actions, and produce structured outputs that the rest of the system relies on.

In practical terms: instead of hard-coding every decision path (“if X then do Y”), you let the model handle the fuzzy parts—language, intent, ambiguity, prioritization—while your code handles what must be precise: permissions, payments, database writes, and policy enforcement.

When AI-first is the right fit (and when it isn’t)

AI-first works best when the problem has:

- Many valid inputs (free text, messy documents, varied user goals)

- Too many edge cases to maintain rules by hand

- Value in judgment, summarization, or synthesis rather than perfect determinism

Rule-based automation is usually better when requirements are stable and exact—tax calculations, inventory logic, eligibility checks, or compliance workflows where output must be the same every time.

Common product goals AI-first supports

Teams typically adopt model-driven logic to:

- Increase speed: draft responses, extract fields, route requests faster

- Personalize experiences: tailor explanations, plans, or recommendations

- Support decisions: highlight tradeoffs, generate options, summarize evidence

The tradeoffs you must accept (and design for)

Models can be unpredictable, sometimes confidently wrong, and their behavior may change as prompts, providers, or retrieved context changes. They also add cost per request, can introduce latency, and raise safety and trust concerns (privacy, harmful outputs, policy violations).

The right mindset is: a model is a component, not a magic answer box. Treat it like a dependency with specs, failure modes, tests, and monitoring—so you get flexibility without betting the product on wishful thinking.

Choose the Right Use Case and Define Success

Not every feature benefits from putting a model in the driver’s seat. The best AI-first use cases start with a clear job-to-be-done and end with a measurable outcome you can track week over week.

Start with the job, not the model

Write a one-sentence job story: “When ___, I want to ___, so I can ___.” Then make the outcome measurable.

Example: “When I receive a long customer email, I want a suggested reply that matches our policies, so I can respond in under 2 minutes.” This is far more actionable than “add an LLM to email.”

Map the decision points

Identify the moments where the model will choose actions. These decision points should be explicit so you can test them.

Common decision points include:

- Classify intent and route to the right workflow

- Decide whether to ask a clarifying question or proceed

- Select tools (search, CRM lookup, drafting, ticket creation)

- Decide when to escalate to a human

If you can’t name the decisions, you’re not ready to ship model-driven logic.

Write acceptance criteria for behavior

Treat model behavior like any other product requirement. Define what “good” and “bad” look like in plain language.

For example:

- Good: uses the latest policy, cites the correct order ID, asks one clear question if info is missing

- Bad: invents discounts, references unsupported locales, or answers without checking required data

These criteria become the foundation for your evaluation set later.

Identify constraints early

List constraints that shape your design choices:

- Time (response latency targets)

- Budget (cost per task)

- Compliance (PII handling, audit requirements)

- Supported locales (languages, tone, cultural expectations)

Define success metrics you can monitor

Pick a small set of metrics tied to the job:

- Task completion rate

- Accuracy (or policy adherence) on representative cases

- CSAT or qualitative user rating

- Time saved per task (or time-to-resolution)

If you can’t measure success, you’ll end up arguing about vibes instead of improving the product.

Design the AI-Driven User Flow and System Boundaries

An AI-first flow isn’t “a screen that calls an LLM.” It’s an end-to-end journey where the model makes certain decisions, the product executes them safely, and the user stays oriented.

Map the end-to-end loop

Start by drawing the pipeline as a simple chain: inputs → model → actions → outputs.

- Inputs: what the user provides (text, files, selections) plus app context (account tier, workspace, recent activity).

- Model step: what the model is responsible for deciding (classify, draft, summarize, choose next action).

- Actions: what your system might do (search, create a task, update a record, send an email).

- Outputs: what the user sees (a draft, an explanation, a confirmation screen, an error with next steps).

This map forces clarity on where uncertainty is acceptable (drafting) versus where it isn’t (billing changes).

Draw system boundaries: model vs deterministic code

Separate deterministic paths (permissions checks, business rules, calculations, database writes) from model-driven decisions (interpretation, prioritization, natural-language generation).

A useful rule: the model can recommend, but code must verify before anything irreversible happens.

Decide where the model runs

Choose a runtime based on constraints:

- Server: best for private data, consistent tooling, audit logs.

- Client: useful for lightweight assistance and privacy-by-local-processing, but harder to control.

- Edge: faster global latency, but limited dependencies.

- Hybrid: split fast intent detection at the edge and heavy work on the server.

Budget latency, cost, and data permissions

Set a per-request latency and cost budget (including retries and tool calls), then design UX around it (streaming, progressive results, “continue in background”).

Document data sources and permissions needed at each step: what the model may read, what it may write, and what requires explicit user confirmation. This becomes a contract for both engineering and trust.

Architecture Patterns: Orchestration, State, and Traces

When a model is part of your app’s logic, “architecture” isn’t just servers and APIs—it’s how you reliably run a chain of model decisions without losing control.

Orchestration: the conductor of model work

Orchestration is the layer that manages how an AI task executes end to end: prompts and templates, tool calls, memory/context, retries, timeouts, and fallbacks.

Good orchestrators treat the model as one component in a pipeline. They decide which prompt to use, when to call a tool (search, database, email, payment), how to compress or fetch context, and what to do if the model returns something invalid.

If you want to move faster from idea to working orchestration, a vibe-coding workflow can help you prototype these pipelines without rebuilding the app scaffolding from scratch. For example, Koder.ai lets teams create web apps (React), backends (Go + PostgreSQL), and even mobile apps (Flutter) via chat—then iterate on flows like “inputs → model → tool calls → validations → UI” with features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback, plus source-code export when you’re ready to own the repo.

State machines for multi-step tasks

Multi-step experiences (triage → gather info → confirm → execute → summarize) work best when you model them as a workflow or state machine.

A simple pattern is: each step has (1) allowed inputs, (2) expected outputs, and (3) transitions. This prevents wandering conversations and makes edge cases explicit—like what happens if the user changes their mind or provides partial info.

Single-shot vs. multi-turn reasoning

Single-shot works well for contained tasks: classify a message, draft a short reply, extract fields from a document. It’s cheaper, faster, and easier to validate.

Multi-turn reasoning is better when the model must ask clarifying questions or when tools are needed iteratively (e.g., plan → search → refine → confirm). Use it intentionally, and cap loops with time/step limits.

Idempotency: avoid repeated side effects

Models retry. Networks fail. Users double-click. If an AI step can trigger side effects—sending an email, booking, charging—make it idempotent.

Common tactics: attach an idempotency key to each “execute” action, store the action result, and ensure retries return the same outcome instead of repeating it.

Traces: make every step debuggable

Add traceability so you can answer: What did the model see? What did it decide? What tools ran?

Log a structured trace per run: prompt version, inputs, retrieved context IDs, tool requests/responses, validation errors, retries, and the final output. This turns “AI did something weird” into an auditable, fixable timeline.

Prompting as Product Logic: Clear Contracts and Formats

When the model is part of your application logic, your prompts stop being “copy” and become executable specifications. Treat them like product requirements: explicit scope, predictable outputs, and change control.

Start with a system prompt that defines the contract

Your system prompt should set the model’s role, what it can and cannot do, and the safety rules that matter for your product. Keep it stable and reusable.

Include:

- Role and goal: who it is (e.g., “support triage assistant”) and what success looks like.

- Scope boundaries: what requests it must refuse or escalate.

- Safety rules: PII handling, medical/legal disclaimers, no guessing.

- Tool policy: when to call tools vs. answer directly.

Structure prompts with clear inputs/outputs

Write prompts like API definitions: list the exact inputs you provide (user text, account tier, locale, policy snippets) and the exact outputs you expect. Add 1–3 examples that match real traffic, including tricky edge cases.

A useful pattern is: Context → Task → Constraints → Output format → Examples.

Use constrained formats for machine-readable results

If code needs to act on the output, don’t rely on prose. Ask for JSON that matches a schema and reject anything else.

{

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"intent": {"type": "string"},

"confidence": {"type": "number", "minimum": 0, "maximum": 1},

"actions": {

"type": "array",

"items": {"type": "string"}

},

"user_message": {"type": "string"}

},

"required": ["intent", "confidence", "actions", "user_message"],

"additionalProperties": false

}

Version prompts and roll out safely

Store prompts in version control, tag releases, and roll out like features: staged deployment, A/B where appropriate, and quick rollback. Log the prompt version with each response for debugging.

Build a prompt test suite

Create a small, representative set of cases (happy path, ambiguous requests, policy violations, long inputs, different locales). Run them automatically on every prompt change, and fail the build when outputs break the contract.

Tool Calling: Let the Model Decide, Let Code Execute

Build orchestration pipelines

Turn inputs to model to tool calls into a real app flow you can test end to end.

Tool calling is the cleanest way to split responsibilities: the model decides what needs to happen and which capability to use, while your application code performs the action and returns verified results.

This keeps facts, calculations, and side effects (creating tickets, updating records, sending emails) in deterministic, auditable code—rather than trusting free-form text.

Design a small, intentional toolset

Start with a handful of tools that cover 80% of requests and are easy to secure:

- Search (your docs/help center) to answer product questions

- DB lookup (read-only first) for user/account/order status

- Calculator for pricing, totals, conversions, and rule-based math

- Ticketing to open support requests when the user needs human follow-up

Keep each tool’s purpose narrow. A tool that does “anything” becomes hard to test and easy to misuse.

Validate inputs, sanitize outputs

Treat the model like an untrusted caller.

- Validate tool inputs with strict schemas (types, ranges, enums). Reject or repair unsafe arguments (e.g., missing IDs, overly broad queries).

- Sanitize tool outputs before handing them back to the model: strip secrets, normalize formats, and return only the fields the model needs.

This reduces prompt-injection risk via retrieved text and limits accidental data leakage.

Add permissions and rate limits per tool

Each tool should enforce:

- Permission checks (who can access which records, which actions)

- Rate limits (per user/session/tool) to reduce abuse and runaway loops

If a tool can change state (ticketing, refunds), require stronger authorization and write an audit log.

Always support a “no tool” path

Sometimes the best action is no action: answer from existing context, ask a clarifying question, or explain limitations.

Make “no tool” a first-class outcome so the model doesn’t call tools just to look busy.

Data and RAG: Make the Model Grounded in Your Reality

If your product’s answers must match your policies, inventory, contracts, or internal knowledge, you need a way to ground the model in your data—not just its general training.

RAG vs. fine-tuning vs. simple context

- Simple context (paste a few paragraphs into the prompt) works when knowledge is small, stable, and you can afford to send it every time (e.g., a short pricing table).

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is best when information is large, frequently changing, or needs citations (e.g., help-center articles, product docs, account-specific data).

- Fine-tuning is best when you want consistent style/format or domain-specific patterns—not as a primary way to “store facts.” Use it to improve how the model writes and follows your rules; pair it with RAG for up-to-date truth.

Ingestion basics: chunking, metadata, freshness

RAG quality is mostly an ingestion problem.

Chunk documents into pieces sized for your model (often a few hundred tokens), ideally aligned to natural boundaries (headings, FAQ entries). Store metadata like: document title, section heading, product/version, audience, locale, and permissions.

Plan for freshness: schedule re-indexing, track “last updated,” and expire old chunks. A stale chunk that ranks highly will quietly degrade the whole feature.

Citations and calibrated answers

Have the model cite sources by returning: (1) answer, (2) a list of snippet IDs/URLs, and (3) a confidence statement.

If retrieval is thin, instruct the model to say what it can’t confirm and offer next steps (“I couldn’t find that policy; here’s who to contact”). Avoid letting it fill the gaps.

Private data: access control and redaction

Enforce access before retrieval (filter by user/org permissions) and again before generation (redact sensitive fields).

Treat embeddings and indexes as sensitive data stores with audit logs.

When retrieval fails: graceful fallbacks

If top results are irrelevant or empty, fall back to: asking a clarifying question, routing to human support, or switching to a non-RAG response mode that explains limitations rather than guessing.

Reliability: Guardrails, Validation, and Caching

When a model sits inside your app logic, “pretty good most of the time” isn’t enough. Reliability means users see consistent behavior, your system can safely consume outputs, and failures degrade gracefully.

Define reliability goals (before you add fixes)

Write down what “reliable” means for the feature:

- Consistent outputs: similar inputs should produce comparable answers (tone, level of detail, constraints).

- Stable formats: the response must be parseable every time (JSON, bullet list, specific fields).

- Bounded behavior: clear limits on what the model should do (no guessing, cite sources, ask a question when uncertain).

These goals become acceptance criteria for both prompts and code.

Guardrails: validate, filter, and enforce policies

Treat model output as untrusted input.

- Schema validation: require a strict format (e.g., JSON with required keys) and reject anything that doesn’t parse.

- Content filters: run profanity checks, PII detectors, or policy validators on both user input and model output.

- Business rules: enforce constraints in code (price ranges, eligibility rules, allowed actions), even if the prompt mentions them.

If validation fails, return a safe fallback (ask a clarifying question, switch to a simpler template, or route to a human).

Retries that actually help

Avoid blind repetition. Retry with a changed prompt that addresses the failure mode:

- “Return valid JSON only. No markdown.”

- “If unsure, set

confidenceto low and ask one question.”

Cap retries and log the reason for each failure.

Deterministic post-processing

Use code to normalize what the model produces:

- canonicalize units, dates, and names

- de-duplicate items

- apply ranking rules or thresholds

This reduces variance and makes outputs easier to test.

Caching without creating privacy problems

Cache repeatable results (e.g., identical queries, shared embeddings, tool responses) to cut cost and latency.

Prefer:

- short TTLs for user-specific data

- cache keys that exclude raw PII (or hash carefully)

- “do not cache” flags for sensitive flows

Done well, caching boosts consistency while keeping user trust intact.

Safety and Trust: Reduce Risk Without Killing UX

Prototype AI logic fast

Build an AI-first workflow with chat, then iterate safely with snapshots and rollback.

Safety isn’t a separate compliance layer you bolt on at the end. In AI-first products, the model can influence actions, wording, and decisions—so safety has to be part of your product contract: what the assistant is allowed to do, what it must refuse, and when it must ask for help.

Key safety concerns to design for

Name the risks your app actually faces, then map each to a control:

- Sensitive data: personal identifiers, credentials, private documents, and anything regulated.

- Harmful guidance: instructions that could enable self-harm, violence, illegal activity, or unsafe medical/financial actions.

- Bias and unfair outcomes: inconsistent quality of service, recommendations, or decisions across groups.

Allowed/blocked topics + escalation paths

Write an explicit policy your product can enforce. Keep it concrete: categories, examples, and expected responses.

Use three tiers:

- Allowed: answer normally.

- Restricted: answer with constraints (e.g., general info only, no step-by-step instructions).

- Blocked: refuse and route to an escalation path (support, resources, or a human agent).

Escalation should be a product flow, not just a refusal message. Provide a “Talk to a person” option, and ensure the handoff includes context the user has already shared (with consent).

Human review for high-impact actions

If the model can trigger real consequences—payments, refunds, account changes, cancellations, data deletion—add a checkpoint.

Good patterns include: confirmation screens, “draft then approve,” limits (amount caps), and a human review queue for edge cases.

Disclosures, consent, and testable policies

Tell users when they’re interacting with AI, what data is used, and what is stored. Ask for consent where needed, especially for saving conversations or using data to improve the system.

Treat internal safety policies like code: version them, document rationale, and add tests (example prompts + expected outcomes) so safety doesn’t regress with every prompt or model update.

Evaluation: Test the Model Like Any Other Critical Component

If an LLM can change what your product does, you need a repeatable way to prove it still works—before users discover regressions for you.

Treat prompts, model versions, tool schemas, and retrieval settings as release-worthy artifacts that require testing.

Build an evaluation set from reality

Collect real user intents from support tickets, search queries, chat logs (with consent), and sales calls. Turn them into test cases that include:

- Common happy-path requests

- Ambiguous prompts that require clarifying questions

- Edge cases (missing data, conflicting constraints, unusual formats)

- Policy-sensitive scenarios (personal data, disallowed content)

Each case should include expected behavior: the answer, the decision taken (e.g., “call tool A”), and any required structure (JSON fields present, citations included, etc.).

Choose metrics that match product risk

One score won’t capture quality. Use a small set of metrics that map to user outcomes:

- Accuracy / task success: did it solve the user’s goal?

- Groundedness: are claims supported by provided context or sources?

- Format validity: does output match the contract (JSON, table, bullets)?

- Refusal rate: does it refuse when it should—and avoid refusing when it shouldn’t?

Track cost and latency alongside quality; a “better” model that doubles response time may hurt conversion.

Run offline evals for every change

Run offline evaluations before release and after every prompt, model, tool, or retrieval change. Keep results versioned so you can compare runs and quickly pinpoint what broke.

Add online tests with guardrails

Use online A/B tests to measure real outcomes (completion rate, edits, user ratings), but add safety rails: define stop conditions (e.g., spikes in invalid outputs, refusals, or tool errors) and roll back automatically when thresholds are exceeded.

Monitoring in Production: Drift, Failures, and Feedback

Build and earn credits

Get credits by sharing what you build or by inviting others to try Koder.ai.

Shipping an AI-first feature isn’t the finish line. Once real users arrive, the model will face new phrasing, edge cases, and changing data. Monitoring turns “it worked in staging” into “it keeps working next month.”

Log what matters (without collecting secrets)

Capture enough context to reproduce failures: the user intent, the prompt version, tool calls, and the model’s final output.

Log inputs/outputs with privacy-safe redaction. Treat logs like sensitive data: strip emails, phone numbers, tokens, and free-form text that might contain personal details. Keep a “debug mode” you can enable temporarily for specific sessions rather than defaulting to maximal logging.

Watch the right signals

Monitor error rates, tool failures, schema violations, and drift. Concretely, track:

- Tool-call success rate and timeouts (did the model pick the right tool, and did it execute?)

- Output format/schema compliance (did your validators reject it?)

- Fallback usage (how often you had to route to a safer or simpler path)

- Content safety blocks (how often you refused or sanitized)

For drift, compare current traffic to your baseline: changes in topic mix, language, average prompt length, and “unknown” intents. Drift isn’t always bad—but it’s always a cue to re-evaluate.

Alerts, runbooks, and incident response

Set alert thresholds and on-call runbooks. Alerts should map to actions: roll back a prompt version, disable a flaky tool, tighten validation, or switch to a fallback.

Plan incident response for unsafe or incorrect behavior. Define who can flip safety switches, how to notify users, and how you’ll document and learn from the event.

Close the loop with user feedback

Use feedback loops: thumbs up/down, reason codes, bug reports. Ask for lightweight “why?” options (wrong facts, didn’t follow instructions, unsafe, too slow) so you can route issues to the right fix—prompt, tools, data, or policy.

UX for Model-Driven Logic: Transparency and Control

Model-driven features feel magical when they work—and brittle when they don’t. UX has to assume uncertainty and still help users finish the job.

Show the “why” without overwhelming people

Users trust AI outputs more when they can see where it came from—not because they want a lecture, but because it helps them decide whether to act.

Use progressive disclosure:

- Start with the outcome (answer, draft, recommendation).

- Offer a “Why?” or “Show work” toggle that reveals key inputs: the user’s request, any tools used, and the sources or records consulted.

- If you use retrieval, show citations that jump to the exact snippet (for example, “Based on: Policy §3.2”). Keep it skimmable.

If you have a deeper explainer, link internally (e.g., /blog/rag-grounding) rather than stuffing the UI with details.

Design for uncertainty (without scary warnings)

A model isn’t a calculator. The interface should communicate confidence and invite verification.

Practical patterns:

- Confidence cues as plain language (“Likely correct”, “Needs review”) instead of fake precision.

- Options, not single answers: “Here are 3 ways to respond.” This reduces the cost of a wrong first guess.

- Confirmations for high-impact actions (sending emails, deleting data, booking payments). Ask a single clear question: “Send this message to 12 recipients?”

Make correction and recovery effortless

Users should be able to steer the output without starting over:

- Inline editing with “Apply changes” so the model continues from the user’s corrections.

- “Regenerate” with controls (tone, length, constraints) rather than a blind reroll.

- “Undo” and a visible history so mistakes are reversible.

Provide an escape hatch

When the model fails—or the user is unsure—offer a deterministic flow or human help.

Examples: “Switch to manual form”, “Use template”, or “Contact support” (e.g., /support). This isn’t a fallback of shame; it’s how you protect task completion and trust.

From Prototype to Production (Without Rebuilding Everything)

Most teams don’t fail because LLMs are incapable; they fail because the path from prototype to a reliable, testable, monitorable feature is longer than expected.

A practical way to shorten that path is to standardize the “product skeleton” early: state machines, tool schemas, validation, traces, and a deploy/rollback story. Platforms like Koder.ai can be useful here when you want to spin up an AI-first workflow quickly—building the UI, backend, and database together—and then iterate safely with snapshots/rollback, custom domains, and hosting. When you’re ready to operationalize, you can export the source code and continue with your preferred CI/CD and observability stack.