Apr 07, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Internal Developer Platforms (IDPs)

Step-by-step guide to plan, build, and ship a web app for an internal developer platform: catalog, templates, workflows, permissions, and auditability.

Step-by-step guide to plan, build, and ship a web app for an internal developer platform: catalog, templates, workflows, permissions, and auditability.

An IDP web app is an internal “front door” to your engineering system. It’s where developers go to discover what already exists (services, libraries, environments), follow the preferred way to build and run software, and request changes without hunting through a dozen tools.

Just as importantly, it’s not another all-in-one replacement for Git, CI, cloud consoles, or ticketing. The goal is to reduce friction by orchestrating what you already use—making the right path the easiest path.

Most teams build an IDP web app because day-to-day work is slowed down by:

The web app should turn these into repeatable workflows and clear, searchable information.

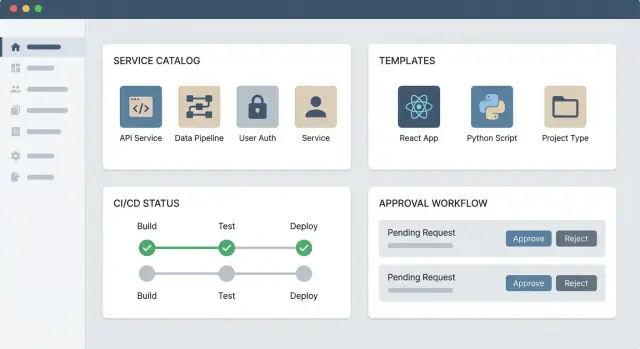

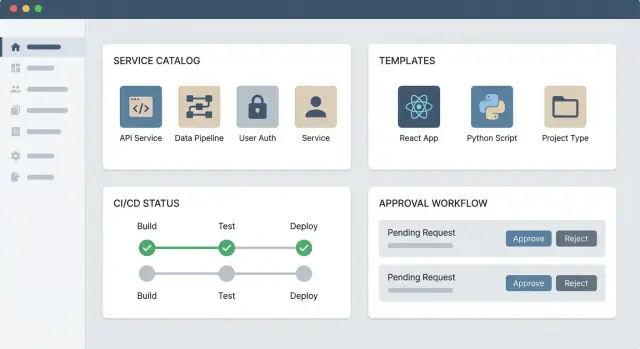

A practical IDP web app usually has three parts:

The platform team typically owns the portal product: the experience, the APIs, the templates, and the guardrails.

Product teams own their services: keeping metadata accurate, maintaining docs/runbooks, and adopting the provided templates. A healthy model is shared responsibility: the platform team builds the paved road; product teams drive on it and help improve it.

An IDP web app succeeds or fails based on whether it serves the right people with the right “happy paths.” Before you pick tooling or draw architecture diagrams, get clear on who will use the portal, what they’re trying to accomplish, and how you’ll measure progress.

Most IDP portals have four core audiences:

If you can’t describe how each group benefits in one sentence, you’re likely building a portal that feels optional.

Choose journeys that happen weekly (not yearly) and make them truly end-to-end:

Write each journey as: trigger → steps → systems touched → expected outcome → failure modes. This becomes your product backlog and your acceptance criteria.

Good metrics tie directly to time saved and friction removed:

Keep it short and visible:

V1 scope: “A portal that lets developers create a service from approved templates, registers it in the service catalog with an owner, and shows deploy + health status. Includes basic RBAC and audit logs. Excludes custom dashboards, full CMDB replacement, and bespoke workflows.”

That statement is your feature-creep filter—and your roadmap anchor for what comes next.

An internal portal succeeds when it solves one painful problem end-to-end, then earns the right to expand. The fastest path is a narrow MVP shipped to a real team within weeks—not quarters.

Start with three building blocks:

This MVP is small, but it delivers a clear outcome: “I can find my service and perform one important action without asking in Slack.”

If you want to validate the UX and workflow “happy path” quickly, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be useful for prototyping the portal UI and orchestration screens from a written workflow spec. Because Koder.ai can generate a React-based web app with a Go + PostgreSQL backend and supports source-code export, teams can iterate fast and still keep long-term ownership of the codebase.

To keep the roadmap organized, group work into four buckets:

This structure prevents a portal that’s “all catalog” or “all automation” with nothing tying it together.

Automate only what meets at least one of these criteria: (1) repeated weekly, (2) error-prone when done manually, (3) requires multi-team coordination. Everything else can be a well-curated link to the right tool, with clear instructions and ownership.

Design the portal so new workflows plug in as additional “actions” on a service or environment page. If every new workflow requires a navigation rethink, adoption will stall. Treat workflows like modules: consistent inputs, consistent status, consistent history—so you can add more without changing the mental model.

A practical IDP portal architecture keeps the user experience simple while handling “messy” integration work reliably behind the scenes. The goal is to give developers one web app, even though actions often span Git, CI/CD, cloud accounts, ticketing, and Kubernetes.

There are three common patterns, and the right choice depends on how fast you need to ship and how many teams will extend the portal:

At minimum, expect these building blocks:

Decide early what the portal “owns” versus what it merely displays:

Integrations fail for normal reasons (rate limits, transient outages, partial success). Design for:

Your service catalog is the source of truth for what exists, who owns it, and how it fits into the rest of the system. A clear data model prevents “mystery services,” duplicate entries, and broken automations.

Start by agreeing what a “service” means in your org. For most teams, it’s a deployable unit (API, worker, website) with a lifecycle.

At minimum, model these fields:

Add practical metadata that powers portals:

Treat relationships as first-class, not just text fields:

primary_owner_team_id plus additional_owner_team_ids).This relational structure enables pages like “everything owned by Team X” or “all services touching this database.”

Decide early on the canonical ID so duplicates don’t appear after imports. Common patterns:

payments-api) enforced as uniquegithub_org/repo) if repos are 1:1 with servicesDocument naming rules (allowed characters, uniqueness, rename policy) and validate them at creation time.

A service catalog fails when it becomes stale. Pick one or combine:

Keep a last_seen_at and data_source field per record so you can show freshness and debug conflicts.

If your internal developer platform (IDP) web app is going to be trusted, it needs three things that work together: authentication (who are you?), authorization (what can you do?), and auditability (what happened, and who did it?). Get these right early and you’ll avoid rework later—especially when the portal starts handling production changes.

Most companies already have identity infrastructure. Use it.

Make SSO via OIDC or SAML the default sign-in path, and pull group membership from your IdP (Okta, Azure AD, Google Workspace, etc.). Then map groups to your portal’s roles and team membership.

This keeps onboarding simple (“log in and you’re already in the right teams”), avoids password storage, and lets IT enforce global policies like MFA and session timeouts.

Avoid a vague “admin vs everyone” model. A practical set of roles for an internal developer platform is:

Keep roles small and understandable. You can always extend later, but a confusing model lowers adoption.

Role-based access control (RBAC) is necessary, but not sufficient. Your portal also needs resource-level permissions: access should be scoped to a team, a service, or an environment.

Examples:

Implement this with a simple policy pattern: (principal) can (action) on (resource) if (condition). Start with team/service scoping and grow from there.

Treat audit logs as a first-class feature, not a backend detail. Your portal should record:

Make audit trails easy to access from the places people work: a service page in the developer portal, a workflow “History” tab, and an admin view for compliance. This also speeds up incident reviews when something breaks.

A good IDP portal UX isn’t about looking fancy—it’s about reducing friction when someone is trying to ship. Developers should be able to answer three questions quickly: What exists? What can I create? What needs attention right now?

Instead of organizing menus by backend systems (“Kubernetes,” “Jira,” “Terraform”), structure the portal around the work developers actually do:

This task-based navigation also makes onboarding easier: new teammates don’t need to know your toolchain to get started.

Every service page should clearly show:

Place this “Who owns this?” panel near the top, not buried in a tab. When incidents happen, seconds matter.

Fast search is the portal’s power feature. Support filters developers naturally use: team, lifecycle (experimental/production), tier, language, platform, and “owned by me.” Add crisp status indicators (healthy/degraded, SLO at risk, blocked by approval) so users can scan a list and decide what to do.

When creating resources, ask only for what’s truly needed now. Use templates (“golden paths”) and defaults to prevent avoidable errors—naming conventions, logging/metrics hooks, and standard CI settings should be pre-filled, not retyped. If a field is optional, hide it behind “Advanced options” so the happy path stays fast.

Self-service is where an internal developer platform earns trust: developers should be able to complete common tasks end-to-end without opening tickets, while platform teams still keep control over safety, compliance, and cost.

Start with a small set of workflows that map to frequent, high-friction requests. Typical “first four”:

These workflows should be opinionated and reflect your golden path, while still allowing controlled choices (language/runtime, region, tier, data classification).

Treat every workflow like a product API. A clear contract makes workflows reusable, testable, and easier to integrate with your toolchain.

A practical contract includes:

Keep the UX focused: surface only the inputs the developer can actually decide, and infer the rest from the service catalog and policy.

Approvals are unavoidable for certain actions (production access, sensitive data, cost increases). The portal should make approvals predictable:

Crucially, approvals should be part of the workflow engine, not a manual side channel. The developer should see status, next steps, and why an approval is required.

Every workflow run should produce a permanent record:

This history becomes your “paper trail” and your support system: when something fails, developers can see exactly where and why—often resolving issues without filing a ticket. It also gives platform teams the data to improve templates and spot recurring failures.

An IDP portal only feels “real” when it can read from and act on the systems developers already use. Integrations turn a catalog entry into something you can deploy, observe, and support.

Most portals need a baseline set of connections:

Be explicit about what data is read-only (e.g., pipeline status) vs write (e.g., trigger a deployment).

API-first integrations are easier to reason about and test: you can validate auth, schemas, and error handling.

Use webhooks for near-real-time events (PR merged, pipeline finished). Use scheduled sync for systems that can’t push events or where eventual consistency is acceptable (e.g., nightly import of cloud accounts).

Create a thin “connector” or “integration service” that normalizes vendor-specific details into a stable internal contract (e.g., Repository, PipelineRun, Cluster). This isolates changes when you migrate tools and keeps your portal UI/API clean.

A practical pattern is:

/deployments/123)Every integration should have a small runbook: what “degraded” looks like, how it’s shown in the UI, and what to do.

Examples:

Keep these docs close to the product (e.g., /docs/integrations) so developers don’t have to guess.

Your IDP portal isn’t just a UI—it’s an orchestration layer that triggers CI/CD jobs, creates cloud resources, updates a service catalog, and enforces approvals. Observability lets you answer, quickly and confidently: “What happened?”, “Where did it fail?”, and “Who needs to act next?”

Instrument each workflow run with a correlation ID that follows the request from the portal UI through backend APIs, approval checks, and external tools (Git, CI, cloud, ticketing). Add request tracing so a single view shows the full path and timing of each step.

Complement traces with structured logs (JSON) that include: workflow name, run ID, step name, target service, environment, actor, and outcome. This makes it easy to filter by “all failed deploy-template runs” or “everything affecting Service X.”

Basic infra metrics aren’t enough. Add workflow metrics that map to real outcomes:

Give platform teams “at a glance” pages:

Link every status to drill-down details and the exact logs/traces for that run.

Set alerts for broken integrations (e.g., repeated 401/403), stuck approvals (no action for N hours), and sync failures. Plan data retention: keep high-volume logs shorter, but retain audit events longer for compliance and investigations, with clear access controls and export options.

Security in an IDP portal works best when it feels like “guardrails,” not gates. The goal is to reduce risky choices by making the safe path the easiest path—while still giving teams autonomy to ship.

Most governance can happen at the moment a developer requests something (a new service, repository, environment, or cloud resource). Treat every form and API call as untrusted input.

Enforce standards in code, not in docs:

This keeps your service catalog clean and makes audits far easier later.

A portal often touches credentials (CI tokens, cloud access, API keys). Treat secrets as radioactive:

Also ensure your audit logs capture who did what and when—without capturing secret values.

Focus on realistic risks:

Mitigate with signed webhook verification, least-privilege roles, and strict separation between “read” and “change” operations.

Run security checks in CI for your portal code and for generated templates (linting, policy checks, dependency scanning). Then schedule regular reviews of:

Governance is sustainable when it’s routine, automated, and visible—not a one-time project.

A developer portal only delivers value if teams actually use it. Treat rollout as a product launch: start small, learn fast, then scale based on evidence.

Pilot with 1–3 teams who are motivated and representative (one “greenfield” team, one legacy-heavy team, one with stricter compliance needs). Watch how they complete real tasks—registering a service, requesting infrastructure, triggering a deploy—and fix friction immediately. The goal isn’t feature completeness; it’s proving the portal saves time and reduces mistakes.

Provide migration steps that fit into a normal sprint. For example:

Keep “day 2” upgrades simple: allow teams to gradually add metadata and replace bespoke scripts with portal workflows.

Write concise docs for the workflows that matter: “Register a service,” “Request a database,” “Roll back a deploy.” Add in-product help next to form fields, and link out to /docs/portal and /support for deeper context. Treat docs like code: version them, review them, and prune them.

Plan ongoing ownership from the beginning: someone must triage the backlog, maintain connectors to external tools, and support users when automations fail. Define SLAs for portal incidents, set a regular cadence for connector updates, and review audit logs to spot recurring pain points and policy gaps.

As your portal matures, you’ll likely want capabilities like snapshots/rollback for portal configuration, predictable deployments, and easy environment promotion across regions. If you’re building or experimenting quickly, Koder.ai can also help teams stand up internal apps with planning mode, deployment/hosting, and code export—useful for piloting portal features before you harden them into long-term platform components.

An IDP web app is an internal developer portal that orchestrates your existing tools (Git, CI/CD, cloud consoles, ticketing, secrets) so developers can follow a consistent “golden path.” It’s not meant to replace those systems of record; it reduces friction by making common tasks discoverable, standardized, and self-service.

Start with problems that happen weekly:

If the portal doesn’t make a frequent workflow faster or safer end-to-end, it will feel optional and adoption will stall.

Keep V1 small but complete:

Ship this to a real team in weeks, then expand based on usage and bottlenecks.

Treat journeys as acceptance criteria: trigger → steps → systems touched → expected outcome → failure modes. Good early journeys include:

Use metrics that reflect friction removed:

A common split is:

Make ownership explicit in the UI (team, on-call, escalation) and back it with permissions so service owners can maintain their entries without platform-team tickets.

Start with a simple, extensible shape:

Keep the systems of record (Git/IAM/CI/cloud) as the source of truth; the portal stores requests and history.

Model services as a first-class entity with:

Use a canonical ID (slug + UUID is common) to prevent duplicates, store relationships (service↔team, service↔resource), and track freshness with fields like and .

Default to enterprise identity:

Record audit events for workflow inputs (with secrets redacted), approvals, and resulting changes, and surface that history on service and workflow pages so teams can self-debug.

Make integrations resilient by design:

Document failure modes in a short runbook under something like /docs/integrations so developers know what to do when an external system is down.

Pick metrics you can instrument from workflow runs, approvals, and integrations—not surveys alone.

last_seen_atdata_source