Nov 11, 2025·8 min

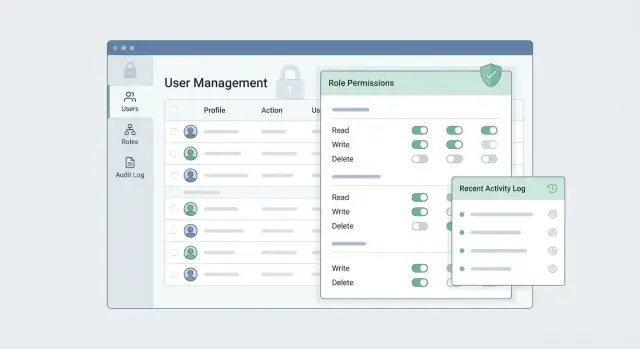

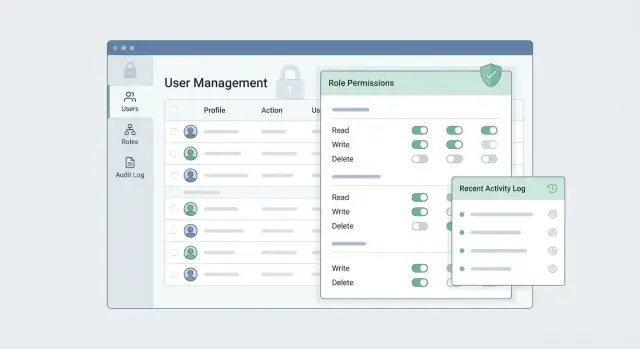

How to Build a Web App to Manage Internal Tool Permissions

Step-by-step guide to designing and building a web app that manages internal tool access with roles, approvals, audit logs, and secure operations.

Step-by-step guide to designing and building a web app that manages internal tool access with roles, approvals, audit logs, and secure operations.

Before you choose RBAC roles and permissions or start designing screens, get specific about what “internal tool permissions” means in your organization. For some teams it’s a simple “who can access which app”; for others it includes fine-grained actions inside each tool, temporary elevations, and audit evidence.

Write down the exact actions you need to control, using verbs that match how people work:

This list becomes the baseline for your access management web app: it determines what you store, what you approve, and what you audit.

Make an inventory of internal systems and tools: SaaS apps, internal admin panels, data warehouses, shared folders, CI/CD, and any “shadow admin” spreadsheets. For each, note whether permissions are enforced:

If enforcement is “by process,” it’s a risk you should either remove or explicitly accept.

Identify decision-makers and operators: IT, security/compliance, team leads, and end users who request access. Agree on success metrics you can measure:

Getting scope right prevents building a permission system that’s too complex to run—or too simple to protect least privilege access.

Your authorization model is the “shape” of your permission system. Get it right early and everything else—UI, approvals, audits, and enforcement—stays simpler.

Most internal tools can begin with role-based access control (RBAC):

RBAC is easiest to explain and review. Add overrides only when you’re seeing frequent “special case” requests. Move to ABAC when you have consistent rules that would otherwise explode your role count (e.g., “can access tool X only for their region”).

Design roles so the default is minimal access, and privilege is earned through explicit assignment:

Define permissions at two levels:

This prevents one tool’s needs from forcing every other tool into the same role structure.

Exceptions are inevitable; make them explicit:

If exceptions become common, it’s a signal to adjust roles or introduce policy rules—without letting “one-offs” turn into permanent, unreviewed privilege.

A permissions app lives or dies by its data model. If you can’t answer “who has access to what, and why?” quickly and consistently, every other feature (approvals, audits, UI) becomes brittle.

Start with a small set of tables/collections that map cleanly to real-world concepts:

export_invoices)Roles should not “float” globally without context. In most internal environments, a role is meaningful only within a tool (e.g., “Admin” in Jira vs “Admin” in AWS).

Expect many-to-many relationships:

If you support team-based inheritance, decide the rule up front: effective access = direct user assignments plus team assignments, with clear conflict handling (e.g., “deny beats allow” if you model denies).

Add fields that explain changes over time:

created_by (who granted it)expires_at (temporary access)disabled_at (soft-disable without losing history)These fields help you answer “was this access valid last Tuesday?”—critical for investigations and compliance.

Your hottest query is usually: “Does user X have permission Y in tool Z?” Index assignments by (user_id, tool_id), and precompute “effective permissions” if checks must be instant. Keep write paths simple, but optimize read paths where enforcement depends on them.

Authentication is how people prove who they are. For an internal permissions app, the goal is to make sign-in easy for employees while keeping admin actions strongly protected.

You typically have three options:

If you support more than one method, pick one as the default and make others explicit exceptions—otherwise admins will struggle to predict how accounts get created.

Most modern integrations use OIDC; many enterprises still require SAML.

Regardless of protocol, decide what you trust from the IdP:

Define session rules up front:

Even if the IdP enforces MFA at login, add step-up authentication for high-impact actions like granting admin rights, changing approval rules, or exporting audit logs. Practically, that means re-checking “MFA performed recently” (or forcing re-auth) before completing the action.

A permissions app succeeds or fails on one thing: whether people can get the access they need without creating silent risk. A clear request and approval workflow keeps access consistent, reviewable, and easy to audit later.

Start with a simple, repeatable path:

Keep requests structured: avoid free-form “please give me admin.” Instead, force selection of a predefined role or permission bundle and require a short justification.

Define approval rules up front so approvals don’t turn into debates:

Use a policy like “manager + app owner” for standard access, and add security as a required step for privileged roles.

Default to time-bound access (for example, 7–30 days) and allow “until revoked” only for a short list of stable roles. Make expiration automatic: the same workflow that grants access should also schedule the removal and notify the user before it ends.

Support an “urgent” path for incident response, but add safeguards:

That way, fast access doesn’t mean invisible access.

Your admin dashboard is where “one click” can grant access to payroll data or revoke production rights. A good UX treats every permission change as a high-stakes edit: clear, reversible, and easy to review.

Use a navigation structure that matches how admins think:

This layout reduces “where do I go?” errors and makes it harder to change the wrong thing in the wrong place.

Permission names should be plain language first, technical detail second. For example:

Show the impact of a role in a short summary (“Grants access to 12 resources, including Production”) and link to the full breakdown.

Use friction intentionally:

Admins need speed without sacrificing safety. Include search, filters (app, role, department, status), and pagination everywhere you list Users, Roles, Requests, and Audit entries. Keep filter state in the URL so pages are shareable and repeatable.

The enforcement layer is where your permission model becomes real. It should be boring, consistent, and hard to bypass.

Create a single function (or small module) that answers one question: “Can user X do action Y on resource Z?” Every UI gate, API handler, background job, and admin tool must call it.

This avoids “close enough” re-implementations that drift over time. Keep inputs explicit (user id, action, resource type/id, context) and outputs strict (allow/deny plus a reason for auditing).

Hiding buttons is not security. Enforce permissions on the server for:

A good pattern is middleware that loads the subject (resource), calls the permission-check function, and fails closed (403) if the decision is “deny.” If you expose a UI that calls /api/reports/export, the export endpoint must enforce the same rule even if the UI already disables the button.

Caching permission decisions can improve performance, but it can also keep access alive after a role change.

Prefer caching inputs that change slowly (role definitions, policy rules), and keep decision caches short-lived. Invalidate caches on events like role updates, user role assignment changes, or deprovisioning. If you must cache per-user decisions, add a “permissions version” counter to the user and bump it on any change.

Avoid:

If you want a concrete reference implementation pattern, document it and link it from your engineering runbook (e.g., /docs/authorization) so new endpoints follow the same enforcement path.

Audit logs are your “receipt system” for permissions. When someone asks, “Why does Alex have access to Payroll?” you should be able to answer in minutes—without guessing or digging through chat.

For every permission change, record who changed what, when, and why. “Why” shouldn’t be free-text only; it should tie back to the workflow that justified the change.

At a minimum, capture:

Finance-Read → Finance-Admin)Use a consistent event schema so reporting is reliable. Even if your UI changes over time, the audit story stays readable.

Not every data read needs a log entry, but access to high-risk data often does. Common examples include payroll details, customer PII exports, API key views, or “download all” actions.

Keep read-logging practical:

Provide basic reports admins actually use: “permissions by person,” “who can access X,” and “changes in the last 30 days.” Include export options (CSV/JSON) for auditors, but treat exports as sensitive actions:

Define retention up front (for example, 1–7 years depending on regulatory needs) and separate duties:

If you add a dedicated “Audit” area in your admin UI, link to it from /admin with clear warnings and a search-first design.

Permissions drift when people join, switch teams, go on leave, or leave the company. A solid access management web app treats user lifecycle as a first-class feature, not an afterthought.

Start with a clear source of truth for identity: your HR system, your IdP (Okta, Azure AD, Google), or both. Your app should be able to:

If your identity provider supports SCIM, use it. SCIM lets you automatically sync users, groups, and status changes into your app, reducing manual admin work and preventing “ghost users.” If SCIM isn’t available, schedule periodic imports (API or CSV) and require owners to review exceptions.

Team moves are where internal tool permissions often get messy. Model “team” as a managed attribute (synced from HR/IdP), and treat role assignments as derived rules where possible (e.g., “If department = Finance, grant Finance Analyst role”).

When someone changes teams, your app should:

Offboarding should revoke access quickly and predictably. Trigger deprovisioning from the IdP (disable user) and have your app immediately:

If your app also provisions access out to downstream tools, queue those removals and surface any failures in the admin dashboard so nothing lingers unnoticed.

A permissions app is an attractive target because it can grant access to many internal systems. Security here isn’t a single feature—it’s a set of small, consistent controls that reduce the chance of an attacker (or a rushed admin) doing damage.

Treat every form field, query parameter, and API payload as untrusted.

Also set safe defaults in your UI: preselect “no access” and require explicit confirmation for high-impact changes.

The UI should reduce mistakes, but it cannot be your security boundary. If an endpoint modifies permissions or reveals sensitive data, it needs a server-side permission check:

This is worth treating as a standard engineering rule: no sensitive endpoint ships without an authorization check and an audit event.

Admin endpoints and authentication flows are frequent targets for brute force and automation.

Where possible, require step-up verification for risky actions (for example, re-authentication or an approval requirement).

Store secrets (SSO client secrets, API tokens) in a dedicated secret manager, not in source code or config files.

Run regular checks for:

These checks are inexpensive and catch the most common ways permission systems fail.

Permissions bugs are rarely “the app is broken” issues—they’re “the wrong person can do the wrong thing” issues. Treat authorization rules as business logic with clear inputs and expected outcomes.

Start by unit testing your permission evaluator (whatever function decides allow/deny). Keep tests readable by naming them like scenarios.

A good pattern is a small table of cases (user state, role, resource, action → expected decision) so adding new rules doesn’t require rewriting the suite.

Unit tests won’t catch wiring mistakes—like a controller forgetting to call the authorization check. Add a few integration tests around the flows that matter most:

These tests should hit the same endpoints your UI uses, validating both API responses and resulting database changes.

Create stable fixtures for roles, teams, tools, and example users (employee, contractor, admin). Keep them versioned and shared across test suites so everyone tests against the same meaning of “Finance Admin” or “Support Read-Only.”

Add a lightweight checklist for permission changes: new roles introduced, default role changes, migrations that touch grants, and any UI changes on admin screens. When possible, link the checklist to your release process (e.g., /blog/release-checklist).

A permissions system is never “set and forget.” The real test starts after launch: new teams onboard, tools change, and urgent access needs show up at the worst time. Treat operations as part of the product, not an afterthought.

Keep dev, staging, and production isolated—especially their data. Staging should mirror production config (SSO settings, policy toggles, feature flags), but use separate identity groups and non-sensitive test accounts.

For permission-heavy apps, also separate:

Monitor the basics (uptime, latency), but add permission-specific signals:

Make alerts actionable: include the user, tool, role/policy evaluated, request ID, and a link to the relevant audit event in your admin UI.

Write short runbooks for common emergencies:

Keep runbooks in the repo and in your ops wiki, and test them during drills.

If you’re implementing this as a new internal app, the biggest risk is spending months on scaffolding (auth flows, admin UI, audit tables, request screens) before you’ve validated the model with real teams. A practical approach is to ship a minimal version quickly, then harden it with policy, logging, and automation.

One way teams do that is with Koder.ai, a vibe-coding platform that lets you create web and backend applications through a chat interface. For permission-heavy apps, it’s especially useful for generating the initial admin dashboard, request/approval flows, and CRUD data model quickly—while still keeping you in control of the underlying architecture (commonly React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend) and allowing source code export when you’re ready to move into your standard review and deployment pipeline. As your needs grow, features like snapshots/rollback and planning mode can help you iterate on authorization rules more safely.

If you want a clearer foundation for role design before scaling operations, see /blog/role-based-access-control-basics. For packaging and rollout options, check /pricing.

A permission is a specific action you want to control, expressed as a verb that matches how people work—e.g., view, edit, admin, or export.

A practical way to start is to list actions per tool and environment (prod vs staging), then standardize names so they’re reviewable and auditable.

Inventory every system where access matters—SaaS apps, internal admin panels, data warehouses, CI/CD, shared folders, and any “shadow admin” spreadsheets.

For each tool, record where enforcement happens:

Anything enforced “by process” should be treated as explicit risk or prioritized for removal.

Track metrics that reflect both speed and safety:

These give you a way to judge whether the system is actually improving operations and reducing risk.

Start with the simplest model that won’t collapse under exceptions:

Pick the simplest approach that stays understandable during reviews and audits.

Make minimal access the default and require explicit assignment for anything more:

Least privilege works best when it’s easy to explain and easy to review.

Define global permissions for org-wide capabilities (e.g., manage users, approve access, view audit logs) and tool-specific permissions for actions inside each tool (e.g., deploy to prod, view secrets).

This prevents one tool’s complexity from forcing every other tool into the same role structure.

At minimum, model:

Add lifecycle fields like created_by, expires_at, and disabled_at so you can answer historical questions (e.g., “Was this access valid last Tuesday?”) without guesswork.

Prefer SSO for internal apps so employees use the corporate identity provider.

Decide whether you trust the IdP for identity only, or identity plus groups (to auto-assign baseline access).

Use a structured flow: request → decision → grant → notify → audit.

Make requests select predefined roles/bundles (not free-form), require a short business justification, and define approval rules like:

Default to time-bound access with automatic expiration.

Log changes as an append-only trail: who changed what, when, and why, including old → new values and links to the request/approval (or ticket) that justified it.

Also: