Nov 29, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Managing Customer Feedback Loops

Learn how to design and build a web app that collects, routes, tracks, and closes customer feedback loops with clear workflows, roles, and metrics.

Learn how to design and build a web app that collects, routes, tracks, and closes customer feedback loops with clear workflows, roles, and metrics.

A feedback management app isn’t “a place to store messages.” It’s a system that helps your team reliably move from input to action to customer-visible follow-up, and then learn from what happened.

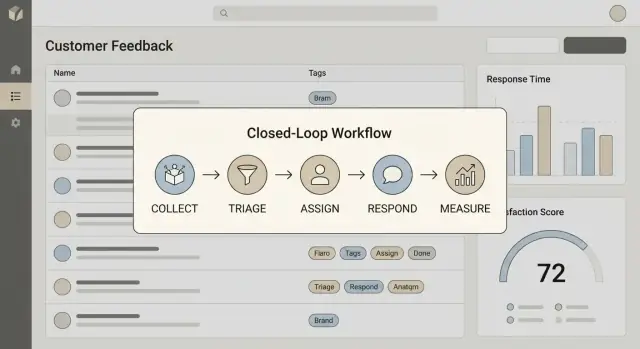

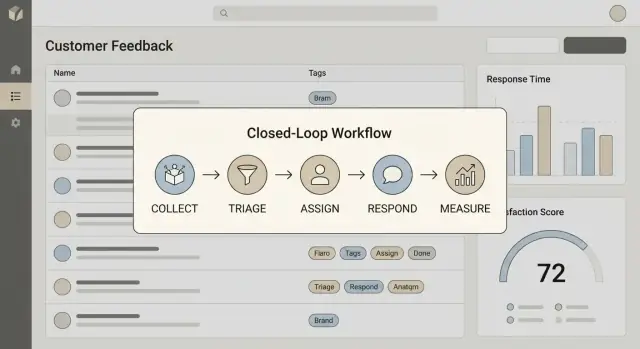

Write a one‑sentence definition your team can repeat. For most teams, closing the loop includes four steps:

If any of these steps is missing, your app will become a backlog graveyard.

Your first version should serve real day‑to‑day roles:

Be specific about the “decisions per click”:

Pick a small set of metrics that reflect speed and quality, such as time to first response, resolution rate, and CSAT change after follow‑up. These become your north star for later design choices.

Before you design screens or pick a database, map what happens to feedback from the moment it’s created to the moment you respond. A simple journey map keeps teams aligned on what “done” means and prevents you from building features that don’t fit real work.

List your feedback sources and note what data each one reliably provides:

Even if inputs differ, your app should normalize them into a consistent “feedback item” shape so teams can triage everything in one place.

A practical first model usually includes:

Statuses to start with: New → Triaged → Planned → In Progress → Shipped → Closed. Keep status meanings written down so “Planned” doesn’t mean “Maybe” for one team and “Committed” for another.

Duplicates are inevitable. Define rules early:

A common approach is to keep one canonical feedback item and link others as duplicates, preserving attribution (who asked) without fragmenting the work.

A feedback loop app succeeds or fails on day one based on whether people can process feedback quickly. Aim for a flow that feels like: “scan → decide → move on,” while still preserving context for later decisions.

Your inbox is the team’s shared queue. It should support quick triage through a small set of powerful filters:

Add “Saved views” early (even if basic), because different teams scan differently: Support wants “urgent + paying,” Product wants “feature requests + high ARR.”

When a user opens an item, they should see:

The goal is to avoid switching tabs just to answer: “Who is this, what did they mean, and have we already responded?”

From the detail view, triage should be one click per decision:

You’ll likely need two modes:

Whichever you choose, make “reply with context” the final step—so closing the loop is part of the workflow, not an afterthought.

A feedback app quickly becomes a shared system of record: product wants themes, support wants fast replies, and leadership wants exports. If you don’t define who can do what (and prove what happened), trust breaks down.

If you’ll serve multiple companies, treat each workspace/org as a hard boundary from day one. Every core record (feedback item, customer, conversation, tags, reports) should include a workspace_id, and every query should be scoped to it.

This isn’t just a database detail—it affects URLs, invitations, and analytics. One safe default: users belong to one or more workspaces, and their permissions are evaluated per workspace.

Keep the first version simple:

Then map permissions to actions, not screens: view vs. edit feedback, merge duplicates, change status, export data, and send replies. This makes it easier to add a “Read-only” role later without rewriting everything.

An audit log prevents “who changed this?” debates. Log key events with actor, timestamp, and before/after where helpful:

Enforce a reasonable password policy, protect endpoints with rate limiting (especially login and ingestion), and secure session handling.

Design with SSO in mind (SAML/OIDC) even if you ship it later: store an identity provider ID and plan for account linking. This keeps enterprise requests from forcing a painful refactor.

Early on, the biggest architecture risk isn’t “will it scale?”—it’s “will we be able to change it quickly without breaking things?” A feedback app evolves fast as you learn how teams actually triage, route, and respond.

A modular monolith is often the best first choice. You get one deployable service, one set of logs, and simpler debugging—while still keeping the codebase organized.

A practical module split looks like:

Think “separate folders and interfaces” before “separate services.” If a boundary becomes painful later (for example, ingestion volume), you can extract it with less drama.

Choose frameworks and libraries your team can ship confidently. A boring, well‑known stack usually wins because:

Novel tooling can wait until you have real constraints (high ingestion rate, strict latency needs, complex permissions). Until then, optimize for clarity and steady delivery.

Most core entities—feedback items, customers, accounts, tags, assignments—fit naturally in a relational database. You’ll want good querying, constraints, and transactions for workflow changes.

If full‑text search and filtering become important, you can add a dedicated search index later (or use built‑in capabilities first). Avoid building two sources of truth too early.

A feedback system quickly accumulates “do this eventually” work: sending email replies, syncing integrations, processing attachments, generating digests, firing webhooks. Put these into a queue/background worker setup from the start.

This keeps the UI responsive, reduces timeouts, and makes failures retryable—without forcing you into microservices on day one.

If your goal is to validate workflow and UI quickly (inbox → triage → replies), consider using a vibe‑coding platform like Koder.ai to generate the first version from a structured chat spec. It can help you stand up a React front end with a Go + PostgreSQL backend, iterate in “planning mode,” and still export the source code when you’re ready to take over a classic engineering workflow.

Your storage layer decides whether your feedback loop feels fast and trustworthy—or slow and confusing. Aim for a schema that’s easy to query for daily work (triage, assignment, status), while still preserving enough raw detail to audit what actually came in.

For an MVP, you can cover most needs with a small set of tables/collections:

A useful rule: keep feedback lean (what you query constantly) and push the “everything else” into events and channel-specific metadata.

When a ticket arrives via email, chat, or a webhook, store the raw incoming payload exactly as received (e.g., original email headers + body, or webhook JSON). This helps you:

Common pattern: an ingestions table with source, received_at, raw_payload (JSON/text/blob), and a link to the created/updated feedback_id.

Most screens boil down to a few predictable filters. Add indexes early for:

(workspace_id, status) for inbox/kanban views(workspace_id, assigned_to) for “my items”(workspace_id, created_at) for sorting and date filters(tag_id, feedback_id) on the join table or a dedicated tag lookup indexIf you support full‑text search, consider a separate search index (or your database’s built‑in text search) rather than piling complex LIKE queries onto production.

Feedback often contains personal data. Decide up front:

Implement retention as a policy per workspace (e.g., 90/180/365 days) and enforce it with a scheduled job that expires raw ingestions first, then older events/replies if required.

Ingestion is where your customer feedback loop either stays clean and useful—or turns into a messy pile. Aim for “easy to send, consistent to process.” Start with a few channels your customers already use, then expand.

A practical first set usually includes:

You don’t need heavyweight filtering on day one, but you do need basic protections:

Normalize every event into one internal format with consistent fields:

Keep both the raw payload and the normalized record so you can improve parsing later without losing data.

Send an immediate confirmation (for email/API/widget when possible): thank them, share what happens next, and avoid promises. Example: “We review every message. If we need more details, we’ll reply. We can’t respond to every request individually, but your feedback is tracked.”

A feedback inbox only stays useful if teams can quickly answer three questions: What is this? Who owns it? How urgent is it? Triage is the part of your app that turns raw messages into organized work.

Freeform tags feel flexible, but they fragment fast (“login”, “log-in”, “signin”). Begin with a small controlled taxonomy that mirrors how your product teams already think:

Allow users to suggest new tags, but require an owner (e.g., PM/Support lead) to approve them. This keeps reporting meaningful later.

Build a simple rules engine that can route feedback automatically based on predictable signals:

Keep rules transparent: show “Routed because: Enterprise plan + keyword ‘SSO’.” Teams trust automation when they can audit it.

Add SLA timers to every item and every queue:

Display SLA status in the list view (“2h left”) and on the detail page, so urgency is shared across the team—not trapped in someone’s head.

Create a clear path when items stall: an overdue queue, daily digests to owners, and a lightweight escalation ladder (Support → Team lead → On-call/Manager). The goal isn’t pressure—it’s preventing important customer feedback from quietly expiring.

Closing the loop is where a feedback management system stops being a “collection box” and becomes a trust‑building tool. The goal is simple: every piece of feedback can be connected to real work, and customers who asked for something can be told what happened—without manual spreadsheets.

Start by letting a single feedback item point to one or more internal work objects (bug, task, feature request). Don’t try to mirror your whole issue tracker—store lightweight references:

work_type (e.g., issue/task/feature)external_system (e.g., jira, linear, github)external_id and optionally external_urlThis keeps your data model stable even if you change tools later. It also enables “show me all customer feedback tied to this release” views without scraping another system.

When linked work moves to Shipped (or Done/Released), your app should be able to notify all customers attached to related feedback items.

Use a templated message with safe placeholders (name, product area, summary, release notes link). Keep it editable at send time to avoid awkward wording. If you have public notes, link them using a relative path like /releases.

Support replies through whichever channel you can reliably send from:

Whatever you choose, track replies per feedback item with an audit‑friendly timeline: sent_at, channel, author, template_id, and delivery status. If a customer replies back, store inbound messages with timestamps too, so your team can prove the loop was actually closed—not just “marked shipped.”

Reporting is only useful if it changes what teams do next. Aim for a few views people can check daily, then expand when you’re confident the underlying workflow data (status, tags, owners, timestamps) is consistent.

Start with operational dashboards that support routing and follow‑up:

Keep the charts simple and clickable so a manager can drill into the exact items that make up a spike.

Add a “customer 360” page that helps support and success teams respond with context:

This view reduces duplicate questions and makes follow‑ups feel intentional.

Teams will ask for exports early. Provide:

Make filtering consistent everywhere (same tag names, date ranges, status definitions). That consistency prevents “two versions of the truth.”

Skip dashboards that only measure activity (tickets created, tags added). Favor outcome metrics tied to action and response: time to first reply, % of items that reached a decision, and recurring issues that were actually addressed.

A feedback loop only works if it lives where people already spend time. Integrations reduce copy‑pasting, keep context close to the work, and make “closing the loop” a habit instead of a special project.

Prioritize the systems your team uses to communicate, build, and track customers:

Keep the first version simple: one‑way notifications + deep links back to your app, then add write‑back actions (e.g., “Assign owner” from Slack) later.

Even if you ship only a few native integrations, webhooks let customers and internal teams connect anything else.

Offer a small, stable set of events:

feedback.createdfeedback.updatedfeedback.closedInclude an idempotency key, timestamps, tenant/workspace id, and a minimal payload plus a URL to fetch full details. This avoids breaking consumers when you evolve your data model.

Integrations fail for normal reasons: revoked tokens, rate limits, network issues, schema mismatches.

Design for this upfront:

If you’re packaging this as a product, integrations are also a buying trigger. Add clear next steps from your app (and marketing site) to /pricing and /contact for teams who want a demo or help connecting their stack.

An effective feedback app isn’t “done” after launch—it gets shaped by how teams actually triage, act, and respond. The goal of your first release is simple: prove the workflow, reduce manual effort, and capture clean data you can trust.

Keep scope tight so you can ship quickly and learn. A practical MVP usually includes:

If a feature doesn’t help a team process feedback end‑to‑end, it can wait.

Early users will forgive missing features, but not lost feedback or incorrect routing. Focus tests where mistakes are expensive:

Aim for confidence in the workflow, not perfect coverage.

Even an MVP needs a few “boring” essentials:

Start with a pilot: one team, a limited set of channels, and a clear success metric (e.g., “respond to 90% of high‑priority feedback within 2 days”). Gather friction points weekly, then iterate the workflow before inviting more teams.

Treat usage data as your roadmap: where people click, where they abandon, which tags are unused, and what “workarounds” reveal the real requirements.

“Closing the loop” means you can reliably move from Collect → Act → Reply → Learn. In practice, every feedback item should end in a visible outcome (shipped, declined, explained, or queued) and—when appropriate—a customer-facing response with a timeframe.

Start with metrics that reflect speed and quality:

Pick a small set so teams don’t optimize for vanity activity.

Normalize everything into a single internal “feedback item” shape, while keeping the original data.

A practical approach:

This keeps triage consistent and lets you reprocess old messages when your parser improves.

Keep the core model simple and query-friendly:

Write down a short, shared status definition and start with a linear set:

Make sure each status answers “what happens next?” and “who owns the next step?” If “Planned” sometimes means “maybe,” split it or rename it so reporting stays trustworthy.

Define duplicates as “same underlying problem/request,” not just similar text.

A common workflow:

This prevents fragmented work while keeping a complete record of demand.

Keep automation simple and auditable:

Always show “Routed because…” so humans can trust and correct it. Start with suggestions or defaults before enforcing hard auto-routing.

Treat each workspace as a hard boundary:

workspace_id to every core recordworkspace_idThen define roles by actions (view/edit/merge/export/send replies), not by screens. Add an early for status changes, merges, assignments, and replies.

Start with a modular monolith and clear boundaries (auth/orgs, feedback, workflow, messaging, analytics). Use a relational database for transactional workflow data.

Add background jobs early for:

This keeps the UI fast and failures retryable without committing to microservices too soon.

Store lightweight references rather than mirroring your whole issue tracker:

external_system (jira/linear/github)work_type (bug/task/feature)external_id (and optional external_url)Then, when linked work is , trigger a workflow to notify all attached customers using templates and tracked delivery status. If you have public notes, link them relatively (e.g., ).

Use the events timeline for auditability and to avoid overloading the main feedback record.

/releases