Mar 18, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Managing Operational Runbooks

Step-by-step guide to building a web app for runbooks: data model, editor, approvals, search, permissions, audit logs, and integrations for incident response.

Step-by-step guide to building a web app for runbooks: data model, editor, approvals, search, permissions, audit logs, and integrations for incident response.

Before you choose features or a tech stack, align on what a “runbook” means in your organization. Some teams use runbooks for incident response playbooks (high-pressure, time-sensitive). Others mean standard operating procedures (repeatable tasks), scheduled maintenance, or customer-support workflows. If you don’t define the scope up front, the app will try to serve every document type—and end up serving none of them well.

Write down the categories you expect the app to hold, with a quick example for each:

Also define minimum standards: required fields (owner, services affected, last reviewed date), what “done” means (every step checked off, notes captured), and what must be avoided (long prose that’s hard to scan).

List the primary users and what they need in the moment:

Different users optimize for different things. Designing for the on-call case usually forces the interface to stay simple and predictable.

Pick 2–4 core outcomes, such as faster response, consistent execution, and easier reviews. Then attach metrics you can track:

These decisions should guide every later choice, from navigation to permissions.

Before you choose a tech stack or sketch screens, watch how operations actually work when something breaks. A runbook management web app succeeds when it fits real habits: where people look for answers, what “good enough” means during an incident, and what gets ignored when everyone is overloaded.

Interview on-call engineers, SREs, support, and service owners. Ask for specific recent examples, not general opinions. Common pain points include scattered docs across tools, stale steps that no longer match production, and unclear ownership (nobody knows who should update a runbook after a change).

Capture each pain point with a short story: what happened, what the team tried, what went wrong, and what would have helped. These stories become acceptance criteria later.

List where runbooks and SOPs live today: wikis, Google Docs, Markdown repos, PDFs, ticket comments, and incident postmortems. For each source, note:

This tells you whether you need a bulk importer, a simple copy/paste migration, or both.

Write down the typical lifecycle: create → review → use → update. Pay attention to who participates at each step, where approvals happen, and what triggers updates (service changes, incident learnings, quarterly reviews).

Even if you’re not in a regulated industry, teams often need answers to “who changed what, when, and why.” Define minimum audit trail requirements early: change summaries, approver identity, timestamps, and the ability to compare versions during incident response playbook execution.

A runbook app succeeds or fails based on whether its data model matches how operations teams actually work: many runbooks, shared building blocks, frequent edits, and high trust in “what was true at the time.” Start by defining the core objects and their relationships.

At minimum, model:

Runbooks rarely live alone. Plan links so the app can surface the right doc under pressure:

Treat versions as append-only records. A Runbook points to a current_draft_version_id and a current_published_version_id.

For steps, store content as Markdown (simple) or structured JSON blocks (better for checklists, callouts, and templates). Keep attachments out of the database: store metadata (filename, size, content_type, storage_key) and put files in object storage.

This structure sets you up for reliable audit trails and a smooth execution experience later.

A runbook app succeeds when it stays predictable under pressure. Start by defining a minimum viable product (MVP) that supports the core loop: write a runbook, publish it, and reliably use it during work.

Keep the first release tight:

If you can’t do these six things quickly, extra features won’t matter.

Once the basics are stable, add capabilities that improve control and insight:

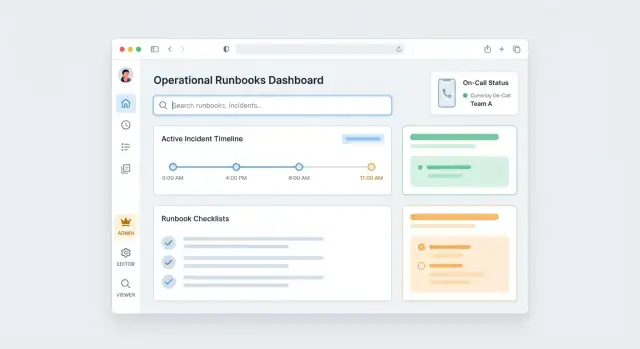

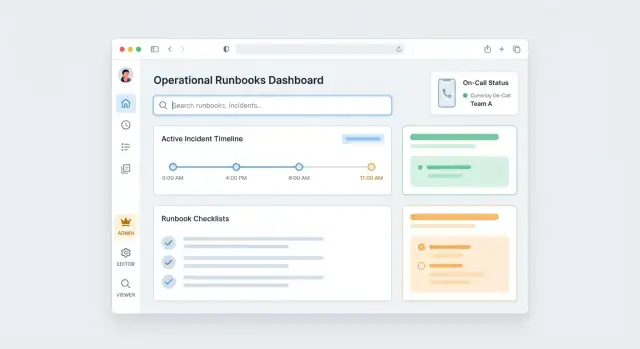

Make the UI map match how operators think:

Design user journeys around roles: an author creating and publishing, a responder searching and executing, and a manager reviewing what’s current and what’s stale.

A runbook editor should make the “right way” to write procedures the easiest way. If people can create clean, consistent steps quickly, your runbooks stay usable when stress is high and time is short.

There are three common approaches:

Many teams start with a block editor and add form-like constraints for critical step types.

Instead of a single long document, store a runbook as an ordered list of steps with types such as:

Typed steps enable consistent rendering, searching, safer reuse, and better execution UX.

Guardrails keep content readable and executable:

Support templates for common patterns (triage, rollback, post-incident checks) and a Duplicate runbook action that copies structure while prompting users to update key fields (service name, on-call channel, dashboards). Reuse reduces variance—and variance is where mistakes hide.

Operational runbooks are only useful when people trust them. A lightweight governance layer—clear owners, a predictable approval path, and recurring reviews—keeps content accurate without turning every edit into a bottleneck.

Start with a small set of statuses that match how teams work:

Make transitions explicit in the UI (e.g., “Request review”, “Approve & publish”), and record who performed each action and when.

Every runbook should have at least:

Treat ownership like an operational on-call concept: owners change as teams change, and those changes should be visible.

When someone updates a published runbook, ask for a short change summary and (when relevant) a required comment like “Why are we changing this step?” This creates shared context for reviewers and reduces back-and-forth during approval.

Runbook reviews only work if people get nudged. Send reminders for “review requested” and “review due soon,” but avoid hard-coding email or Slack. Define a simple notification interface (events + recipients), then plug in providers later—Slack today, Teams tomorrow—without rewriting core logic.

Operational runbooks often contain exactly the kind of information you don’t want broadly shared: internal URLs, escalation contacts, recovery commands, and occasionally sensitive configuration details. Treat authentication and authorization as a core feature, not a later hardening task.

At minimum, implement role-based access control with three roles:

Keep these roles consistent across the UI (buttons, editor access, approvals) so users don’t have to guess what they can do.

Most organizations organize operations by team or service, and permissions should follow that structure. A practical model is:

For higher-risk content, add an optional runbook-level override (e.g., “only Database SREs can edit this runbook”). This keeps the system manageable while still supporting exceptions.

Some steps should be visible only to a smaller group. Support restricted sections such as “Sensitive details” that require elevated permission to view. Prefer redaction (“hidden to viewers”) over deleting content so the runbook still reads coherently under pressure.

Even if you start with email/password, design the auth layer so you can add SSO later (OAuth, SAML). Use a pluggable approach for identity providers and store stable user identifiers so switching to SSO doesn’t break ownership, approvals, or audit trails.

When something is broken, nobody wants to browse documentation. They want the right runbook in seconds, even if they only remember a vague term from an alert or a teammate’s message. Findability is a product feature, not a nice-to-have.

Implement one search box that scans more than titles. Index titles, tags, owning service, and step content (including commands, URLs, and error strings). People often paste a log snippet or alert text—step-level search is what turns that into a match.

Support tolerant matching: partial words, typos, and prefix queries. Return results with highlighted snippets so users can confirm they’ve found the right procedure without opening five tabs.

Search is fastest when users can narrow the context. Provide filters that reflect how ops teams think:

Make filters sticky across sessions for on-call users, and show active filters prominently so it’s clear why results are missing.

Teams don’t use one vocabulary. “DB,” “database,” “postgres,” “RDS,” and an internal nickname might all mean the same thing. Add a lightweight synonym dictionary that you can update without redeploying (admin UI or config). Use it at query time (expand search terms) and optionally at indexing time.

Also capture common terms from incident titles and alert labels to keep synonyms aligned with reality.

The runbook page should be information-dense and skimmable: a clear summary, prerequisites, and a table of contents for steps. Show key metadata near the top (service, environment applicability, last reviewed, owner) and keep steps short, numbered, and collapsible.

Include a “copy” affordance for commands and URLs, and a compact “related runbooks” area to jump to common follow-ups (e.g., rollback, verification, escalation).

Execution mode is where your runbooks stop being “documentation” and become a tool people can rely on under time pressure. Treat it like a focused, distraction-free view that guides someone from first step to last, while capturing what actually happened.

Each step should have a clear status and a simple control surface:

Small touches help: pin the current step, show “next up,” and keep long steps readable with collapsible details.

While executing, operators need to attach context without leaving the page. Allow per-step additions such as:

Make these additions timestamped automatically, and preserve them even if the run is paused and resumed.

Real procedures aren’t linear. Support “if/then” branching steps so a runbook can adapt to conditions (e.g., “If error rate > 5%, then…”). Also include explicit Stop and escalate actions that:

Every run should create an immutable execution record: runbook version used, step timestamps, notes, evidence, and final outcome. This becomes the source of truth for post-incident review and for improving the runbook without relying on memory.

When a runbook changes, the question during an incident isn’t “what’s the latest version?”—it’s “can we trust it, and how did it get here?” A clear audit trail turns runbooks into dependable operational records instead of editable notes.

At minimum, log every meaningful change with who, what, and when. Go one step further and store before/after snapshots of the content (or a structured diff) so reviewers can see exactly what changed without guessing.

Capture events beyond editing, too:

This creates a timeline you can rely on during post-incident reviews and compliance checks.

Give users an Audit tab per runbook showing a chronological stream of changes with filters (editor, date range, event type). Include “view this version” and “compare to current” actions so responders can quickly confirm they’re following the intended procedure.

If your organization needs it, add export options like CSV/JSON for audits. Keep exports permissioned and scoped (single runbook or a time window), and consider linking to an internal admin page like /settings/audit-exports.

Define retention rules that match your requirements: for example, keep full snapshots for 90 days, then retain diffs and metadata for 1–7 years. Store audit records append-only, restrict deletion, and record any administrative overrides as auditable events themselves.

Your runbooks become dramatically more useful when they’re one click away from the alert that triggered the work. Integrations also reduce context switching during incidents, when people are stressed and time is tight.

Most teams can cover 80% of needs with two patterns:

A minimal incoming payload can be as small as:

{

"service": "payments-api",

"event_type": "5xx_rate_high",

"severity": "critical",

"incident_id": "INC-1842",

"source_url": "https://…"

}

Design your URL scheme so an alert can point directly to the best match, usually by service + event type (or tags like database, latency, deploy). For example:

/runbooks/123/runbooks/123/execute?incident=INC-1842/runbooks?service=payments-api&event=5xx_rate_highThis makes it easy for alerting systems to include the URL in notifications, and for humans to land on the right checklist without extra searching.

Hook into Slack or Microsoft Teams so responders can:

If you already have docs for integrations, link them from your UI (for example, /docs/integrations) and expose configuration where ops teams expect it (a settings page plus a quick test button).

A runbook system is part of your operational safety net. Treat it like any other production service: deploy predictably, protect it from common failures, and improve it in small, low-risk steps.

Start with a hosting model your ops team can support (managed platform, Kubernetes, or a simple VM setup). Whatever you choose, document it in its own runbook.

Backups should be automatic and tested. It’s not enough to “take snapshots”—you need confidence you can restore:

For disaster recovery, decide your targets up front: how much data you can afford to lose (RPO) and how quickly you need the app back (RTO). Keep a lightweight DR checklist that includes DNS, secrets, and a verified restore procedure.

Runbooks are most valuable under pressure, so aim for fast page loads and predictable behavior:

Also log slow queries early; it’s easier than guessing later.

Focus tests on the features that, if broken, create risky behavior:

Add a small set of end-to-end tests for “publish a runbook” and “execute a runbook” to catch integration issues.

Pilot with one team first—ideally the group with frequent on-call work. Collect feedback in the tool (quick comments) and in short weekly reviews. Expand gradually: add the next team, migrate the next set of SOPs, and refine templates based on real usage rather than assumptions.

If you want to move from concept to a working internal tool quickly, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you prototype the runbook management web app end-to-end from a chat-driven specification. You can iterate on core workflows (library → editor → execution mode), then export the source code when you’re ready to review, harden, and run it within your standard engineering process.

Koder.ai is especially practical for this kind of product because it aligns with common implementation choices (React for the web UI; Go + PostgreSQL for the backend) and supports planning mode, snapshots, and rollback—useful when you’re iterating on operationally critical features like versioning, RBAC, and audit trails.

Define the scope up front: incident response playbooks, SOPs, maintenance tasks, or support workflows.

For each runbook type, set minimum standards (owner, service(s), last reviewed date, “done” criteria, and a bias toward short, scannable steps). This prevents the app from becoming a generic document dump.

Start with 2–4 outcomes and attach measurable metrics:

These metrics help you prioritize features and detect whether the app is actually improving operations.

Watch real workflows during incidents and routine work, then capture:

Turn those stories into acceptance criteria for search, editing, permissions, and versioning.

Model these core objects:

Use many-to-many links where reality demands it (runbook↔service, runbook↔tags) and store references to alert rules/incident types so integrations can suggest the right playbook quickly.

Treat versions as append-only, immutable records.

A practical pattern is a Runbook pointing to:

current_draft_version_idcurrent_published_version_idEditing creates new draft versions; publishing promotes a draft into a new published version. Keep old published versions for audits and postmortems; consider pruning only draft history if needed.

Your MVP should reliably support the core loop:

If these are slow or confusing, “nice-to-haves” (templates, analytics, approvals, executions) won’t get used under pressure.

Pick an editor style that matches your team:

Make steps first-class objects (command/link/decision/checklist/caution) and add guardrails like required fields, link validation, and a preview that matches execution mode.

Use a distraction-free checklist view that captures what happened:

Store each run as an immutable execution record tied to the runbook version used.

Implement search as a primary product feature:

Also design the runbook page for scanning: short steps, strong metadata, copy buttons, and related runbooks.

Start with simple RBAC (Viewer/Editor/Admin) and scope access by team or service, with optional runbook-level overrides for high-risk content.

For governance, add:

Log audits as append-only events (who/what/when, publish actions, approvals, ownership changes) and design auth to accommodate future SSO (OAuth/SAML) without breaking identifiers.