Apr 18, 2025·8 min

Build an Open-Source Project Website with Community Input

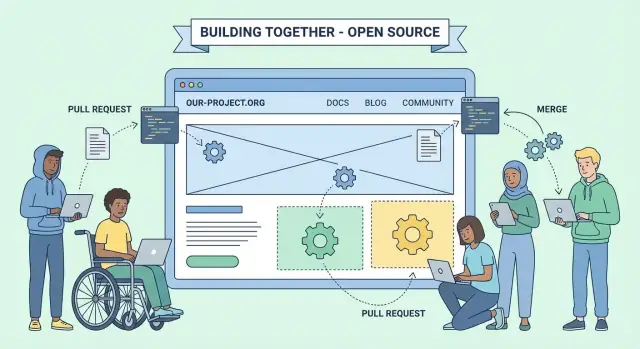

Learn how to plan, build, and maintain an open-source project website that welcomes community contributions with clear workflows, review steps, and reliable publishing.

Clarify the Website’s Purpose and Audience

Before you pick a theme or wireframe a homepage, get specific about what the site is for. Open-source websites often try to be everything at once—docs portal, marketing page, community hub, blog, donation funnel—and end up doing none of it well.

Define the primary goals

Write down the top 1–3 jobs the website must accomplish. Common examples:

- Documentation: help users succeed quickly (install, tutorials, API reference).

- Downloads: make it obvious where to get releases, packages, or containers.

- Community: show how to ask questions, join chat, find issues, or attend meetings.

- Updates: publish release notes, announcements, and roadmap changes.

If you can’t explain the website’s purpose in one sentence, visitors won’t be able to either.

Identify the audiences (and what they need)

List your main audiences and the “first click” you want each group to take:

- Users want a quick start, troubleshooting, and version-specific docs.

- Contributors want clear contribution steps and “good first issues.”

- Maintainers want a low-friction publishing process and predictable reviews.

- Sponsors want proof of impact and an easy way to support the project.

A useful exercise: for each audience, write the top 3 questions they arrive with (e.g., “How do I install?”, “Is this actively maintained?”, “Where do I report a bug?”).

Pick success metrics you can actually measure

Choose simple metrics that connect to your goals and are realistic to track:

- Docs goal → traffic to key docs pages, search queries, time-to-first-success guide.

- Community goal → number of first-time contributors, issues triaged, PRs merged.

- Updates goal → newsletter sign-ups, RSS subscribers, release post views.

State non-goals to prevent scope creep

Explicitly list what the site will not do (for now): custom web apps, complex account systems, heavy integrations, or bespoke CMS features. This protects maintainers’ time and keeps the project shippable.

Decide what the community can edit vs. maintainer-only

Split content into two buckets:

- Community-editable: docs, FAQs, tutorials, translations, examples, typo fixes.

- Maintainer-only: security pages, legal/policy text, governance decisions, official statements.

This single decision will shape your tool choices, review workflow, and contributor experience later.

Plan the Site Structure and Content Model

A community website gets messy fast if you don’t decide what “belongs” on the site versus what should stay in the repository. Before tools and themes, agree on a simple structure and a clear content model—so contributors know where to add things and maintainers know how to review them.

Start with a sitemap that matches how people think

Keep the primary navigation boring on purpose. A good default sitemap for an open-source project website is:

- Home: what the project is, why it exists, quick links

- Docs: getting started, guides, API/reference, FAQ

- Blog/News: releases, announcements, community highlights

- Community: chat/forum links, events, code of conduct

- Contribute: “how to help,” beginner issues, contribution steps

- Governance: decision-making, maintainers, policies

If a page doesn’t fit one of these, it’s a signal you may be adding something internal (better suited for the repo) or something that needs its own content type.

Decide what lives on the website vs. the repo README

Use the README for developer-facing essentials: build instructions, local dev setup, testing, and quick project status. Use the website for:

- Onboarding content for new users and contributors

- Longer guides and tutorials

- Public-facing policies (Code of Conduct, governance)

- Release notes and announcements

This separation prevents duplicated content that drifts out of sync.

Define ownership, tone, and versioning up front

Assign content owners by area (docs, blog/news, translations). Ownership can be a small group with clear review responsibility, not a single gatekeeper.

Write a short tone and style guide that’s friendly to a global community: plain language, consistent terminology, and guidance for non-native English writers.

If your project ships releases, plan for versioned docs early (for example: “latest” plus supported versions). It’s much easier to design the structure now than to retrofit it after multiple releases.

Pick a Tech Stack That Supports Contributions

Your website stack should make it simple for someone to fix a typo, add a new page, or improve docs without becoming a build engineer. For most open-source projects, that means: Markdown-first content, quick local setup, and a smooth pull-request workflow with previews.

If you expect to iterate quickly on layout and navigation, consider prototyping the site experience before you commit to a long-lived stack. Platforms like Koder.ai can help you sketch a docs/marketing site via chat, generate a working React-based UI with a backend when needed, and then export the source code to maintain in your repo—useful for exploring information architecture and contribution flows without weeks of setup.

Static site generators that work well for community edits

Here’s how common options stack up for contribution-friendly docs and project sites:

- Docusaurus: Great for docs websites with versioning, sidebar navigation, and built-in search options. Local setup is straightforward (Node), and it’s optimized for PR-based documentation.

- MkDocs (especially with Material): Very approachable for contributors—write Markdown, edit

mkdocs.yml, and run one command. Search is typically strong and fast. - Hugo: Extremely fast builds and flexible content types. Slightly more “theme/template” complexity, but excellent when you want both docs and a richer marketing site.

- Jekyll: Works seamlessly with GitHub Pages, but can feel less ergonomic than newer tools. Still fine for simpler sites.

- Astro: Excellent for modern, content-heavy sites and component-based pages. Best when you expect more custom UI work beyond docs.

Hosting and previews: prioritize “PR → preview → merge”

Choose hosting that supports preview builds so contributors can see their changes live before publishing:

- GitHub Pages / GitLab Pages: Simple and familiar; previews may require extra CI configuration.

- Netlify / Cloudflare Pages: Strong PR preview support out of the box, plus easy rollbacks.

If you can, make the default path “open a PR, get a preview link, request review, merge.” That reduces maintainer back-and-forth and boosts contributor confidence.

Write down the decision so newcomers don’t guess

Add a short docs/website-stack.md (or a section in README.md) explaining what you chose and why: how to run the site locally, where previews appear, and which kinds of changes belong in the website repo.

Set Up the Repository for Collaboration

A welcoming repo makes the difference between “drive-by edits” and sustained community contributions. Aim for a structure that’s easy to navigate, predictable for reviewers, and simple to run locally.

Recommended repo layout

Keep web-related files grouped and clearly named. One common approach is:

/

/website # marketing pages, landing, navigation

/docs # documentation source (reference, guides)

/blog # release notes, announcements, stories

/static # images, icons, downloadable assets

/.github # issue templates, workflows, CODEOWNERS

README.md # repo overview

If your project already has application code, consider placing the site in /website (or /site) so contributors don’t have to guess where to start.

Add a focused README inside /website

Create /website/README.md that answers: “How do I preview my change?” Keep it short and copy-paste friendly.

Example quickstart (adjust to your stack):

# Website quickstart

## Requirements

- Node.js 20+

## Install

npm install

## Run locally

npm run dev

## Build

npm run build

## Lint (optional)

npm run lint

Also include where key files live (navigation, footer, redirects) and how to add a new page.

Provide content templates people can copy

Templates reduce formatting debates and speed up reviews. Add a /templates folder (or document templates in /docs/CONTRIBUTING.md).

/templates

docs-page.md

tutorial.md

announcement.md

A minimal docs page template might look like:

---

title: "Page title"

description: "One-sentence summary"

---

## What you’ll learn

## Steps

## Troubleshooting

Route reviews with CODEOWNERS (when applicable)

If you have maintainers for specific areas, add /.github/CODEOWNERS so the right people get requested automatically:

/docs/ @docs-team

/blog/ @community-team

/website/ @web-maintainers

Keep configuration minimal and well-commented

Prefer one canonical config file per tool, and add brief comments explaining “why” (not every option). The goal is that a new contributor can confidently change a menu item or fix a typo without learning your entire build system.

Create Contribution Guidelines People Will Follow

Prototype the core pages fast

Prototype docs, blog, and contribute pages before you commit to a long stack.

A website attracts a different kind of contribution than the codebase: copy edits, new examples, screenshots, translations, and small UX tweaks. If your CONTRIBUTING.md is written only for developers, you’ll lose a lot of potential help.

Make CONTRIBUTING.md “website-first”

Create (or split out) a CONTRIBUTING.md that focuses on website changes: where content lives, how pages are generated, and what “done” looks like. Add a short “common tasks” table (fix a typo, add a new page, update navigation, publish a blog post) so newcomers can start in minutes.

If you already have deeper guidance, link it clearly from CONTRIBUTING.md (for example, a walkthrough page under /docs).

Explain how to propose edits (issues vs PRs)

Be explicit about when to open an issue first versus sending a direct PR:

- Open an issue first for new pages, structural changes, or anything that needs discussion (tone, positioning, major design changes).

- Direct PRs are welcome for typos, broken links, small clarifications, and obvious updates.

Include a “good issue template” snippet: what page URL, what change, why it helps readers, and any sources.

Set review expectations people can trust

Most frustration comes from silence, not feedback. Define:

- Typical response time (e.g., “we acknowledge within 3 business days”)

- Required approvals (e.g., one maintainer + one docs reviewer for new pages)

- Style checks (linters, formatting, link checker, spelling) and whether contributors should run them locally

Add a content checklist for every PR

A lightweight checklist prevents back-and-forth:

- Links work (prefer relative links for internal pages)

- Screenshots are current and have alt text

- Headings are scannable; tone matches existing docs

- Accessibility basics: color contrast, keyboard-friendly patterns, descriptive link text

- Changelog note if the change affects users

Design the Review and Publishing Workflow

A community website stays healthy when contributors know exactly what happens after they open a pull request. The goal is a workflow that is predictable, low-friction, and safe to ship.

Start with a PR template that reduces back-and-forth

Add a pull request template (for example, .github/pull_request_template.md) that asks only what reviewers need:

- What changed? (one or two sentences)

- Why? (issue link or context)

- Screenshots (for visual changes—before/after)

- Content checklist (spelling, links, frontmatter)

This structure speeds reviews and teaches contributors what “good” looks like.

Make every PR clickable with preview deployments

Enable preview deployments so reviewers can see the change running as a real site. This is especially helpful for navigation updates, styling, and broken layouts that don’t show up in a text diff.

Common pattern:

- PR opened → CI builds the site

- Hosting provider posts a preview URL back to the PR

- Reviewers click, verify, and request changes if needed

Automate the boring (and error-prone) checks

Use CI to run lightweight gates on every PR:

- Link checker to catch broken internal/external links

- Markdown lint to keep formatting consistent

- Formatting (Prettier or similar) to avoid style debates

Fail fast, with clear error messages, so contributors can fix issues without maintainer intervention.

Keep publishing simple: merge to main deploys

Document one rule: when a PR is approved and merged to main, the site deploys automatically. No manual steps, no secret commands. Put the exact behavior in /contributing so expectations are clear.

If you use a platform that supports snapshots/rollback (some hosts do, and so does Koder.ai when you deploy through it), document where to find the “last known good” build and how to restore it.

Write down rollback steps before you need them

Deployments break sometimes. Document a short rollback playbook:

- Revert the merge commit (or restore the last known-good tag)

- Confirm the deploy re-runs

- Open a follow-up issue explaining what happened and how to prevent it

Build a Consistent Design System for Content

A community website stays welcoming when pages feel like they belong to the same place. A lightweight design system helps contributors move faster, reduces review nitpicks, and keeps readers oriented—even as the site grows.

Start with reusable page layouts and navigation rules

Define a small set of page “types” and stick to them: docs page, blog/news post, landing page, and reference page. For each type, decide what always appears (title, summary, last updated, table of contents, footer links) and what never should.

Set navigation rules that protect clarity:

- Keep top-level navigation categories stable; add new pages inside existing groups first.

- Avoid more than 3 levels of nesting in sidebars.

- Require new pages to declare where they live in the hierarchy (for example, a

sidebar_positionorweight).

Create content components people can reuse

Instead of asking contributors to “make it look consistent,” give them building blocks:

- Callouts for notes, warnings, and tips

- Standard code blocks with language tags, line wrap rules, and copy buttons (if supported)

- API reference patterns (endpoint table, parameters, responses, examples)

Document these components in a short “Content UI Kit” page (for example, /docs/style-guide) with copy‑paste examples.

Keep branding lightweight

Define the minimum: logo usage (where it can’t be stretched or recolored), 2–3 core colors with accessible contrast, and one or two fonts. The goal is to make “good enough” easy, not to police creativity.

Make screenshots and diagrams easy to maintain

Agree on conventions: fixed widths, consistent padding, and naming like feature-name__settings-dialog.png. Prefer source files for diagrams (e.g., Mermaid or editable SVG) so updates don’t require a designer.

Protect the information hierarchy

Add a simple checklist to PR templates: “Is there already a page for this?”, “Does the title match the section it’s in?”, and “Will this create a new top-level category?” This prevents content sprawl while still encouraging contributions.

Make the Site Accessible, Fast, and Discoverable

Collaborate on site changes

Use Koder.ai to iterate on structure and copy with maintainers and contributors.

A community website only works if people can actually use it—on assistive tech, on slow connections, and through search. Treat accessibility, performance, and SEO as defaults, not polish added at the end.

Accessibility: hit the baseline every time

Start with semantic structure. Use headings in order (H1 on the page, then H2/H3), and don’t skip levels just to get a bigger font.

For non-text content, require meaningful alt text. A simple rule: if an image conveys information, describe it; if it’s purely decorative, use empty alt (alt="") so screen readers can skip it.

Check color contrast and focus states in your design tokens so contributors don’t have to guess. Make sure every interactive element is reachable by keyboard, and that focus doesn’t get trapped in menus, dialogs, or code examples.

Performance: keep the page light

Optimize images by default: resize to the maximum display size, compress, and prefer modern formats where your build supports them. Avoid loading large client-side bundles for pages that are mostly text.

Keep third‑party scripts to a minimum. Each extra widget adds weight and can slow down the site for everyone.

Lean on caching defaults provided by your host (for example, immutable assets with hashes). If your static site generator supports it, generate minified CSS/JS and inline only what’s truly critical.

Discoverability: simple SEO that works

Give every page a clear title and a short meta description that matches what the page delivers. Use clean, stable URLs (no dates unless they matter) and consistent canonical paths.

Generate a sitemap and a robots.txt that allows indexing of public docs. If you publish multiple versions of documentation, avoid duplicate content by making one version “current” and clearly linking to others.

Analytics and licensing: be transparent

Only add analytics if you will act on the data. If you do, explain what is collected, why, and how to opt out on a dedicated page (for example, /privacy).

Finally, include a clear license notice for the website content (separate from the code license if needed). Put it in the footer and in your repository README so contributors know how their text and images can be reused.

Create the Core Pages That Help People Join In

Your website’s core pages are the “front desk” for new contributors. If they answer the obvious questions quickly—what the project is, how to try it, and where help is needed—more people will move from curiosity to action.

Start with onboarding: “What is this project?” and “Quickstart”

Create a plain-language overview page that explains what the project does, who it’s for, and what success looks like. Include a few concrete examples and a short “Is this for you?” section.

Then add a Quickstart page that is optimized for momentum: one path to a first successful run, with copy‑paste commands and a short troubleshooting block. If setup differs by platform, keep the main path short and link out to detailed guides.

Suggested pages:

- /docs/overview — “What is this project?”

- /docs/quickstart — the shortest working path

Create a “Contribute” hub that routes people to the right work

A single /contribute page should point to:

- Good first issues (link to a filtered issue list)

- Documentation tasks (a labeled issue queue or

/docs/contributing) - Translation/localization work (how to add a locale, where strings live)

Keep it specific: name 3–5 tasks you actually want done this month, and link to the exact issue(s).

Community pages that set expectations

Publish the essentials as first-class pages, not buried in a repo:

- Code of Conduct (and how to report issues)

- Chat/community links (Discord/Matrix/Slack) and response-time expectations

- Meeting notes (a simple archive:

/community/meetings)

Release notes/changelog with a repeatable template

Add /changelog (or /releases) with a consistent format: date, highlights, upgrade notes, and links to PRs/issues. Templates reduce maintainer effort and make community-written notes easier to review.

Showcase adopters/plugins—only if you can keep it current

A showcase page can motivate contributions, but stale lists hurt credibility. If you add /community/showcase, set a lightweight rule (e.g., “review quarterly”) and provide a small submission form or PR template.

Support Ongoing Community Updates and Localization

Go beyond a static site

When you need more than static pages, add a Go backend with PostgreSQL.

A community site stays healthy when updates are easy, safe, and rewarding—even for first‑time contributors. Your goal is to reduce “where do I click?” friction and make small improvements feel worthwhile.

Make every page editable in one click

Add a clear “Edit this page” link on docs, guides, and even FAQs. Point it directly to the file in your repo so it opens a pull request (PR) flow with minimal steps.

Keep the link text friendly (for example: “Fix a typo” or “Improve this page”) and place it near the top or bottom of the content. If you have a contributing guide, link it right there too (e.g., /contributing).

Support translations with a simple, predictable structure

Localization works best when the folder layout answers questions at a glance. A common approach is:

- /docs/en/…

- /docs/es/…

- /docs/ja/…

Document the review steps: who can approve translations, how you handle partial translations, and how you track what’s outdated. Consider adding a short note at the top of translated pages when they lag behind the source language.

Add “latest vs stable” guidance (and versioned docs if needed)

If your project has releases, make it obvious what users should read:

- “Latest” for current development

- “Stable” for the most recent release

Even without full docs versioning, a small banner or selector that explains the difference prevents confusion and reduces support load.

Keep FAQs and troubleshooting easy to update

Put FAQs in the same content system as your docs (not buried in issue comments). Link to it prominently (e.g., /docs/faq) and encourage people to contribute fixes when they hit a problem.

Encourage small, high-impact contributions

Explicitly invite quick wins: typo fixes, clearer examples, updated screenshots, and “this worked for me” troubleshooting notes. These are often the best entry point for new contributors—and they steadily improve your open-source project website.

If you want to incentivize writing and maintenance work, be transparent about what you reward and why. For example, some teams offer small sponsorships or credits; Koder.ai has an “earn credits” program for creating content about the platform, which can be adapted as inspiration for lightweight, community-friendly recognition systems.

Maintain the Website Without Burning Out Maintainers

A community-driven site should feel welcoming—but not at the cost of a few people doing endless cleanup. The goal is to make maintenance predictable, lightweight, and shareable.

Set simple maintenance routines

Pick a cadence people can remember and automate what you can.

- Weekly (automated): broken link checks, basic spellcheck, and build tests in CI.

- Monthly (15–30 minutes): review open website PRs/issues, merge small fixes, close stale threads with a friendly note.

- Quarterly: dependency updates for your static site generator and plugins, plus a quick accessibility spot-check.

If you document this schedule in /CONTRIBUTING.md (and keep it short), others can step in confidently.

Define governance for content decisions

Content disagreements are normal: tone, naming, what belongs on the homepage, or whether a blog post is “official.” Avoid drawn-out debates by writing down:

- Who has final editorial approval (e.g., “Website Maintainers” or a rotating editor).

- How disputes are resolved (time-box discussion, propose alternatives, then decide).

- What qualifies as “official” vs. “community” content.

This is less about control and more about clarity.

Keep a lightweight content calendar

A calendar doesn’t need to be fancy. Create a single issue (or a simple markdown file) listing upcoming:

- releases

- events/talks

- security notices

- monthly project updates

Link to it from blog/news planning notes so contributors can self-assign.

Make it easy for newcomers to help

Track recurring website issues (typos, outdated screenshots, missing links, accessibility fixes) and label them “good first issue.” Include clear acceptance criteria like “update one page + run formatter + screenshot the result.”

Add troubleshooting for local setup

Put a short “Common local setup issues” section in your docs. Example:

# clean install

rm -rf node_modules

npm ci

npm run dev

Also mention the top 2–3 gotchas you see often (wrong Node version, missing Ruby/Python dependency, port already in use). This reduces back-and-forth and saves maintainer energy.

FAQ

How do I decide what my open-source project website is actually for?

Write a one-sentence purpose statement, then list the top 1–3 jobs the site must do (for example: docs, downloads, community, updates). If a page or feature doesn’t support those jobs, treat it as a non-goal for now.

A simple check: if you can’t explain the site’s purpose in one sentence, visitors won’t be able to either.

Which audiences should the site serve, and how do I design for them?

List your main audiences and define the first click you want from each:

- Users → Quickstart, install, troubleshooting

- Contributors → contribution steps, “good first issues”

- Maintainers → publishing workflow, review expectations

- Sponsors → impact proof, how to support

For each audience, write the top 3 questions they arrive with (e.g., “Is this maintained?”, “Where do I report a bug?”) and ensure your navigation answers them quickly.

What’s a good default sitemap for an open-source website?

Start with a “boring on purpose” sitemap that matches how people search:

- Home

- Docs

- Blog/News

- Community

- Contribute

- Governance

If new content doesn’t fit, it’s a sign you either need a new content type (rare) or the information belongs in the repo instead of the website.

What should live on the website vs. in the repository README?

Keep developer workflow in the README and public onboarding on the website.

Use the repo README for:

- Build/test instructions

- Local dev setup

- quick project status

Use the website for:

Which static site generator is best for community contributions?

Pick a stack that supports “Markdown-first” edits and quick local preview.

Common choices:

- Docusaurus: great for doc versioning + sidebars

- : simple for contributors; strong search

How do I set up previews so contributors can see changes before they’re published?

Aim for a default path of PR → preview → review → merge.

Practical approach:

- Enable preview builds with a host that posts a preview URL to the PR

- Document where previews appear and how to request review

- Keep deployment rules simple (for example, “merge to

maindeploys”)

This reduces reviewer back-and-forth and gives contributors confidence their change looks right.

What repository setup makes website contributions easier?

Use structure and templates to reduce formatting debates.

Helpful basics:

What should a CONTRIBUTING guide include for a community website?

Make it “website-first” and specific.

Include:

- Where content lives and how pages are generated

- When to open an issue vs. when a direct PR is welcome

- Expected response times and required approvals

- A small PR checklist (links, screenshots/alt text, tone, accessibility basics)

Keep it short enough that people will actually read it—and link to deeper docs when needed.

How do I keep the site accessible, fast, and discoverable?

Treat these as defaults, not optional polish:

- Use semantic headings in order (don’t skip levels)

- Ensure keyboard navigation works (visible focus states, no trapped focus)

- Provide meaningful alt text for informative images; use empty alt for decorative ones

- Optimize images (resize + compress) and keep third-party scripts minimal

- Add clear titles and meta descriptions; keep URLs stable

Add automated checks where possible (link checker, Markdown lint, formatting) so reviewers aren’t doing it manually.

How do we support ongoing updates, translations, and long-term maintenance without burnout?

Make updates easy and maintenance predictable.

For community updates:

- Add an “Edit this page” link that points directly to the source file

- Keep FAQs/troubleshooting in the same docs system (e.g.,

/docs/faq) - Use a predictable translation structure like

/docs/en/...,/docs/es/...

For maintainer sustainability: