Nov 12, 2025·8 min

Build a Website Ready for AI Crawlers and LLM Indexing

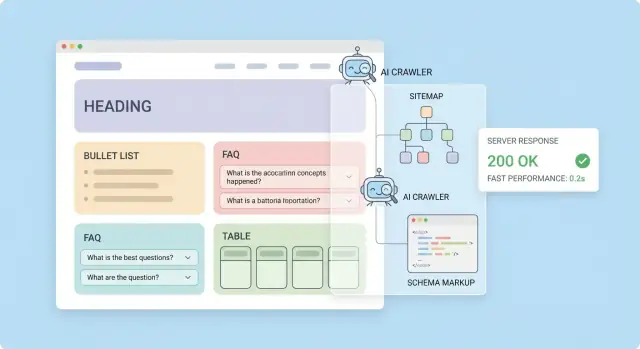

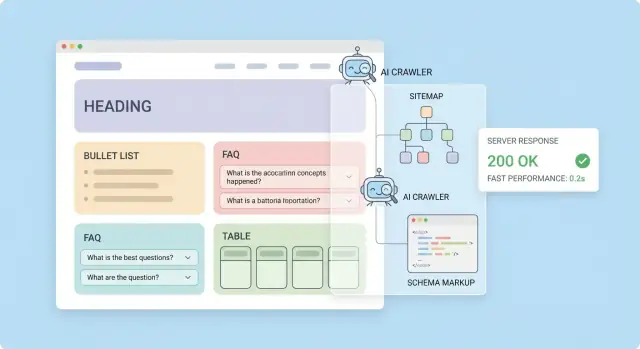

Learn how to structure content, metadata, crawl rules, and performance so AI crawlers and LLM tools can discover, parse, and cite your pages reliably.

Learn how to structure content, metadata, crawl rules, and performance so AI crawlers and LLM tools can discover, parse, and cite your pages reliably.

“AI-optimized” is often used as a buzzword, but in practice it means your website is easy for automated systems to find, read, and reuse accurately.

When people say AI crawlers, they usually mean bots operated by search engines, AI products, or data providers that fetch web pages to power features like summaries, answers, training datasets, or retrieval systems. LLM indexing typically refers to turning your pages into a searchable knowledge store (often “chunked” text with metadata) so an AI assistant can retrieve the right passage and cite or quote it.

AI optimization is less about “ranking” and more about four outcomes:

No one can guarantee inclusion in any particular AI index or model. Different providers crawl differently, respect different policies, and refresh on different schedules.

What you can control is making your content straightforward to access, extract, and attribute—so if it’s used, it’s used correctly.

llms.txt file to guide LLM-focused discoveryIf you’re building new pages and flows quickly, it helps to choose tooling that doesn’t fight these requirements. For example, teams using Koder.ai (a chat-driven vibe-coding platform that generates React frontends and Go/PostgreSQL backends) often bake in SSR/SSG-friendly templates, stable routes, and consistent metadata early—so “AI-ready” becomes a default, not a retrofit.

LLMs and AI crawlers don’t interpret a page the way a person does. They extract text, infer relationships between ideas, and try to map your page to a single, clear intent. The more predictable your structure is, the fewer wrong assumptions they need to make.

Start by making the page easy to scan in plain text:

A useful pattern is: promise → summary → explanation → proof → next steps.

Place a short summary near the top (2–5 lines). This helps AI systems quickly classify the page and capture the key claims.

Example TL;DR:

TL;DR: This page explains how to structure content so AI crawlers can extract the main topic, definitions, and key takeaways reliably.

LLM indexing works best when each URL answers one intent. If you mix unrelated goals (e.g., “pricing,” “integration docs,” and “company history” on one page), the page becomes harder to categorize and may surface for the wrong queries.

If you need to cover related but distinct intents, split them into separate pages and connect them with internal links (e.g., /pricing, /docs/integrations).

If your audience could interpret a term multiple ways, define it early.

Example:

AI crawler optimization: preparing site content and access rules so automated systems can reliably discover, read, and interpret pages.

Pick one name for each product, feature, plan, and key concept—and stick to it everywhere. Consistency improves extraction (“Feature X” always refers to the same thing) and reduces entity confusion when models summarize or compare your pages.

Most AI indexing pipelines break pages into chunks and store/retrieve the best-matching pieces later. Your job is to make those chunks obvious, self-contained, and easy to quote.

Keep one H1 per page (the page’s promise), then use H2s for the major sections someone might search for, and H3s for subtopics.

A simple rule: if you could turn your H2s into a table of contents that describes the full page, you’re doing it right. This structure helps retrieval systems attach the right context to each chunk.

Avoid vague labels like “Overview” or “More info.” Instead, make headings answer the user’s intent:

When a chunk is pulled out of context, the heading often becomes its “title.” Make it meaningful.

Use short paragraphs (1–3 sentences) for readability and to keep chunks focused.

Bullet lists work well for requirements, steps, and feature highlights. Tables are great for comparisons because they preserve structure.

| Plan | Best for | Key limit |

|---|---|---|

| Starter | Trying it out | 1 project |

| Team | Collaboration | 10 projects |

A small FAQ section with blunt, complete answers improves extractability:

Q: Do you support CSV uploads?

A: Yes—CSV up to 50 MB per file.

Close key pages with navigation blocks so both users and crawlers can follow intent-based paths:

AI crawlers don’t all behave like a full browser. Many can fetch and read raw HTML immediately, but struggle (or simply skip) executing JavaScript, waiting for API calls, and assembling the page after hydration. If your key content only appears after client-side rendering, you risk being “invisible” to systems doing LLM indexing.

With a traditional HTML page, the crawler downloads the document and can extract headings, paragraphs, links, and metadata right away.

With a JS-heavy page, the first response might be a thin shell (a few divs and scripts). The meaningful text shows up only after scripts run, data loads, and components render. That second step is where coverage drops: some crawlers won’t run scripts; others run them with timeouts or partial support.

For pages you want indexed—product descriptions, pricing, FAQs, docs—favor:

The goal isn’t “no JavaScript.” It’s meaningful HTML first, JS second.

Tabs, accordions, and “read more” controls are fine if the text is in the DOM. Problems happen when tab content is fetched only after a click, or injected after a client-side request. If that content matters for AI discovery, include it in the initial HTML and use CSS/ARIA to control visibility.

Use both of these checks:

If your headings, main copy, internal links, or FAQ answers appear only in Inspect Element but not in View Source, treat it as a rendering risk and move that content into server-rendered output.

AI crawlers and traditional search bots both need clear, consistent access rules. If you accidentally block important content—or allow crawlers into private or “messy” areas—you can waste crawl budget and pollute what gets indexed.

Use robots.txt for broad rules: what entire folders (or URL patterns) should be crawled or avoided.

A practical baseline:

/admin/, /account/, internal search results, or parameter-heavy URLs that generate near-infinite combinations.Example:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /admin/

Disallow: /account/

Disallow: /internal-search/

Sitemap: /sitemap.xml

Important: blocking with robots.txt prevents crawling, but it doesn’t always guarantee a URL won’t appear in an index if it’s referenced elsewhere. For index control, use page-level directives.

Use meta name="robots" in HTML pages and X-Robots-Tag headers for non-HTML files (PDFs, feeds, generated exports).

Common patterns:

noindex,follow so links still pass through but the page itself stays out of indexes.noindex alone—protect with authentication, and consider also disallowing crawl.noindex plus proper canonicalization (covered later).Document—and enforce—rules per environment:

noindex globally (header-based is easiest) to avoid accidental indexing.If your access controls affect user data, make sure the user-facing policy matches reality (see /privacy and /terms when relevant).

If you want AI systems (and search crawlers) to reliably understand and cite your pages, you need to reduce “same content, many URLs” situations. Duplicates waste crawl budget, split signals, and can cause the wrong version of a page to be indexed or referenced.

Aim for URLs that stay valid for years. Avoid exposing unnecessary parameters such as session IDs, sorting options, or tracking codes in indexable URLs (for example: ?utm_source=..., ?sort=price, ?ref=). If parameters are required for functionality (filters, pagination, internal search), ensure the “main” version is still accessible at a stable, clean URL.

Stable URLs improve long-term citations: when an LLM learns or stores a reference, it’s far more likely to keep pointing to the same page if your URL structure doesn’t change every redesign.

Add a <link rel="canonical"> on pages where duplicates are expected:

Canonical tags should point to the preferred, indexable URL (and ideally that canonical URL should return a 200 status).

When a page moves permanently, use a 301 redirect. Avoid redirect chains (A → B → C) and loops; they slow down crawlers and can lead to partial indexing. Redirect old URLs directly to the final destination, and keep redirects consistent across HTTP/HTTPS and www/non-www.

Implement hreflang only when you have genuinely localized equivalents (not just translated snippets). Incorrect hreflang can create confusion about which page should be cited for which audience.

Sitemaps and internal links are your “delivery system” for discovery: they tell crawlers what exists, what matters, and what should be ignored. For AI crawlers and LLM indexing, the goal is simple—make your best, cleanest URLs easy to find and hard to miss.

Your sitemap should include only indexable, canonical URLs. If a page is blocked by robots.txt, marked noindex, redirected, or isn’t the canonical version, it doesn’t belong in the sitemap. This keeps crawler budgets focused and reduces the chance that an LLM picks up a duplicate or outdated version.

Be consistent with URL formats (trailing slashes, lowercase, HTTPS) so the sitemap mirrors your canonical rules.

If you have lots of URLs, split them into multiple sitemap files (common limit: 50,000 URLs per file) and publish a sitemap index that lists each sitemap. Organize by content type when it helps, e.g.:

/sitemaps/pages.xml/sitemaps/blog.xml/sitemaps/docs.xmlThis makes maintenance easier and helps you monitor what’s being discovered.

lastmod as a trust signal, not a deployment timestampUpdate lastmod thoughtfully—only when the page meaningfully changes (content, pricing, policy, key metadata). If every URL updates on every deploy, crawlers learn to ignore the field, and genuinely important updates may be revisited later than you’d like.

A strong hub-and-spoke structure helps both users and machines. Create hubs (category, product, or topic pages) that link to the most important “spoke” pages, and ensure each spoke links back to its hub. Add contextual links in copy, not just in menus.

If you publish educational content, keep your main entry points obvious—send users to /blog for articles and /docs for deeper reference material.

Structured data is a way to label what a page is (an article, product, FAQ, organization) in a format machines can read reliably. Search engines and AI systems don’t have to guess which text is the title, who wrote it, or what the main entity is—they can parse it directly.

Use Schema.org types that match your content:

Pick one primary type per page, then add supporting properties (for example, an Article can reference an Organization as the publisher).

AI crawlers and search engines compare structured data to the visible page. If your markup claims an FAQ that isn’t actually on the page, or lists an author name that’s not shown, you create confusion and risk having the markup ignored.

For content pages, include author plus datePublished and dateModified when they’re real and meaningful. This makes freshness and accountability clearer—two things LLMs often look for when deciding what to trust.

If you have official profiles, add sameAs links (e.g., your company’s verified social profiles) to your Organization schema.

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "Article",

"headline": "Build a Website Ready for AI Crawlers and LLM Indexing",

"author": { "@type": "Person", "name": "Jane Doe" },

"datePublished": "2025-01-10",

"dateModified": "2025-02-02",

"publisher": {

"@type": "Organization",

"name": "Acme",

"sameAs": ["https://www.linkedin.com/company/acme"]

}

}

Finally, validate with common testing tools (Google’s Rich Results Test, Schema Markup Validator). Fix errors, and treat warnings pragmatically: prioritize the ones tied to your chosen type and key properties (title, author, dates, product info).

An llms.txt file is a small, human-readable “index card” for your site that points language-model-focused crawlers (and the people configuring them) to the most important entry points: your docs, key product pages, and any reference material that explains your terminology.

It’s not a standard with guaranteed behavior across all crawlers, and you shouldn’t treat it as a replacement for sitemaps, canonicals, or robots controls. Think of it as a helpful shortcut for discovery and context.

Put it at the site root so it’s easy to find:

/llms.txtThat’s the same idea as robots.txt: predictable location, quick fetch.

Keep it short and curated. Good candidates:

Also consider adding brief style notes that reduce ambiguity (for example, “We call customers ‘workspaces’ in our UI”). Avoid long marketing copy, full URL dumps, or anything that conflicts with your canonical URLs.

Here’s a simple example:

# llms.txt

# Purpose: curated entry points for understanding and navigating this site.

## Key pages

- / (Homepage)

- /pricing

- /docs

- /docs/getting-started

- /docs/api

- /blog

## Terminology and style

- Prefer “workspace” over “account”.

- Product name is “Acme Cloud” (capitalized).

- API objects: “Project”, “User”, “Token”.

## Policies

- /terms

- /privacy

Consistency matters more than volume:

robots.txt (it creates mixed signals).A practical routine that stays manageable:

llms.txt and confirm it’s still the best entry point.llms.txt whenever you update your sitemap or change canonicals.Done well, llms.txt stays small, accurate, and genuinely useful—without making promises about how any particular crawler will behave.

Crawlers (including AI-focused ones) behave a lot like impatient users: if your site is slow or flaky, they’ll fetch fewer pages, retry less often, and refresh their index less frequently. Good performance and reliable server responses increase the odds that your content is discovered, re-crawled, and kept up to date.

If your server frequently times out or returns errors, a crawler may back off automatically. That means new pages can take longer to show up, and updates may not be reflected quickly.

Aim for steady uptime and predictable response times during peak hours—not just great “lab” scores.

Time to First Byte (TTFB) is a strong signal of server health. A few high-impact fixes:

Even though crawlers don’t “see” images like people do, large files still waste crawl time and bandwidth.

Crawlers rely on status codes to decide what to keep and what to drop:

If the main article text requires authentication, many crawlers will only index the shell. Keep core reading access public, or provide a crawlable preview that includes the key content.

Protect your site from abuse, but avoid blunt blocks. Prefer:

Retry-After headersThis keeps your site safe while still letting responsible crawlers do their job.

“E‑E‑A‑T” doesn’t require grand claims or fancy badges. For AI crawlers and LLMs, it mostly means your site is clear about who wrote something, where facts came from, and who is accountable for maintaining it.

When you state a fact, attach the source as close to the claim as possible. Prioritize primary and official references (laws, standards bodies, vendor docs, peer‑reviewed papers) over secondhand summaries.

For example, if you mention structured data behavior, cite Google’s documentation (“Google Search Central — Structured Data”) and, when relevant, the schema definitions (“Schema.org vocabulary”). If you discuss robots directives, reference the relevant standards and official crawler docs (e.g., “RFC 9309: Robots Exclusion Protocol”). Even if you don’t link out on every mention, include enough detail that a reader can locate the exact document.

Add an author byline with a short bio, credentials, and what the author is responsible for. Then make ownership explicit:

Avoid “best” and “guaranteed” language. Instead, describe what you tested, what changed, and what the limits are. Add update notes at the top or bottom of key pages (e.g., “Updated 2025‑12‑10: clarified canonical handling for redirects”). This creates a maintenance trail that both humans and machines can interpret.

Define your core terms once, then use them consistently across the site (e.g., “AI crawler,” “LLM indexing,” “rendered HTML”). A lightweight glossary page (e.g., /glossary) reduces ambiguity and makes your content easier to summarize accurately.

An AI-ready site isn’t a one-time project. Small changes—like a CMS update, a new redirect, or a redesigned navigation—can quietly break discovery and indexing. A simple testing routine keeps you from guessing when traffic or visibility shifts.

Start with the basics: track crawl errors, index coverage, and your top-linked pages. If crawlers can’t fetch key URLs (timeouts, 404s, blocked resources), LLM indexing tends to degrade quickly.

Also monitor:

After launches (even “small” ones), review what changed:

A 15-minute post-release audit often catches issues before they become long-term visibility losses.

Pick a handful of high-value pages and test how they’re summarized by AI tools or internal summarization scripts. Look for:

If summaries are vague, the fix is usually editorial: stronger H2/H3 headings, clearer first paragraphs, and more explicit terminology.

Turn what you learn into a periodic checklist and assign an owner (a real name, not “marketing”). Keep it living and actionable—then link the latest version internally so the whole team uses the same playbook. Publish a lightweight reference like /blog/ai-seo-checklist and update it as your site and tooling evolve.

If your team ships fast (especially with AI-assisted development), consider adding “AI readiness” checks directly into your build/release workflow: templates that always output canonical tags, consistent author/date fields, and server-rendered core content. Platforms like Koder.ai can help here by making those defaults repeatable across new React pages and app surfaces—and by letting you iterate via planning mode, snapshot, and rollback when a change accidentally impacts crawlability.

Small, steady improvements compound: fewer crawl failures, cleaner indexing, and content that’s easier for both people and machines to understand.

It means your site is easy for automated systems to discover, parse, and reuse accurately.

In practice, that comes down to crawlable URLs, clean HTML structure, clear attribution (author/date/sources), and content written in self-contained chunks that retrieval systems can match to specific questions.

Not reliably. Different providers crawl on different schedules, follow different policies, and may not crawl you at all.

Focus on what you can control: make your pages accessible, unambiguous, fast to fetch, and easy to attribute so that if they’re used, they’re used correctly.

Aim for meaningful HTML in the initial response.

Use SSR/SSG/hybrid rendering for important pages (pricing, docs, FAQs). Then enhance with JavaScript for interactivity. If your main text only appears after hydration or API calls, many crawlers will miss it.

Compare:

If key headings, main copy, links, or FAQs show up only in Inspect Element, move that content into server-rendered HTML.

Use robots.txt for broad crawl rules (e.g., block /admin/), and meta robots / X-Robots-Tag for indexing decisions per page or file.

A common pattern is noindex,follow for thin utility pages, and authentication (not just ) for private areas.

Use a stable, indexable canonical URL for each piece of content.

rel="canonical" where duplicates are expected (filters, parameters, variants).This reduces split signals and makes citations more consistent over time.

Include only canonical, indexable URLs.

Exclude URLs that are redirected, noindex, blocked by robots.txt, or non-canonical duplicates. Keep formats consistent (HTTPS, trailing slash rules, lowercase), and use lastmod only when content meaningfully changes.

Treat it like a curated “index card” that points to your best entry points (docs hubs, getting started, glossary, policies).

Keep it short, list only URLs you want discovered and cited, and ensure every link returns 200 with the correct canonical. Don’t use it as a replacement for sitemaps, canonicals, or robots directives.

Write pages so chunks can stand alone:

This improves retrieval accuracy and reduces wrong summaries.

Add and maintain visible trust signals:

datePublished and meaningful dateModifiedThese cues make attribution and citation more reliable for both crawlers and users.

noindex