Nov 19, 2025·8 min

Product bundle pricing math: clear discounts and accurate stock

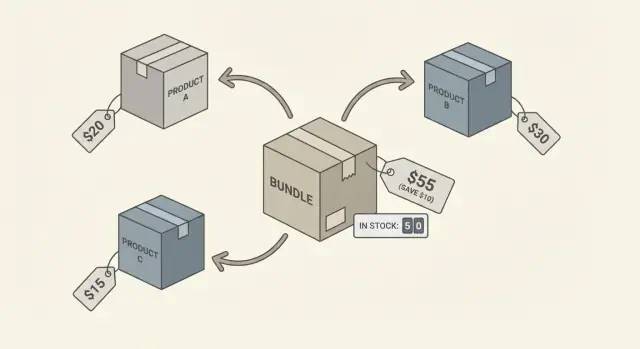

Learn product bundle pricing math to show discounts clearly, measure margins, and keep component inventory accurate with simple models and checks.

Why bundles break pricing and inventory if you wing it

Bundles feel simple to shoppers: “buy these together and save.” But inside your store, they touch pricing, tax, promos, COGS, and stock at the same time. If you do not set clear rules, you get a checkout that looks right while reports quietly drift away from reality.

Two things usually go wrong first: the discount is unclear, and stock counts become unreliable. A customer might see a bundle price, then also see extra promo codes, “compare at” prices, or per-item discounts stacked in a way that makes the savings hard to understand. Internally, your systems may not agree on whether the bundle sold as one unit or as multiple items.

Here are the two main risks to watch:

- Unclear discounts: customers cannot tell what they saved, support gets more “was I charged right?” tickets, and finance cannot explain revenue in plain terms.

- Wrong stock counts: you sell a kit, but only the kit SKU goes down, not the components, so you oversell parts or freeze cash in excess inventory.

A bundle can also look profitable but lose money. This happens when revenue is recorded at the bundle level, but costs are tracked at the component level (or not tracked at all). You might see a healthy “bundle gross margin” in a dashboard, while the real cost of one expensive component is being ignored, discounted twice, or refunded more often than expected.

“Accurate” should mean four practical things:

-

Checkout matches the promise: the customer can see the bundle price and the savings in one consistent way.

-

Sales reporting is explainable: you can answer, “How many units of each item did we actually move?” and “How much discount did we give?”

-

Inventory stays honest: when one bundle ships, the right quantity of each component is deducted, even if the warehouse picks from separate bins.

-

Returns do not corrupt data: if a customer returns one item from a kit, your system knows how to adjust revenue, discount, and stock without guessing.

If you start with clear product bundle pricing math and a single inventory rule, the rest of the bundle decisions get much easier.

Common bundle and kit types (and what they imply)

Before you do any product bundle pricing math, name the bundle type. The type decides what customers see, how you measure margin, and how stock should move.

A pure bundle is “these items must be bought together.” Think “camera body + lens + bag” sold as one deal. This usually needs one clear bundle price, a clear discount story (compared to buying each item), and consistent inventory deduction across the same components every time.

A mix-and-match set is “pick any 3 from this group.” Pricing and stock get trickier because the components vary. You often need rules like “same price no matter what” (simple, but margins can swing) or “price depends on chosen items” (clearer margins, more complexity).

Kits, multipacks, and assortments sound similar but behave differently:

- A kit is a curated set of different SKUs that solves a job (starter kit, repair kit). Customers expect guidance and a meaningful discount.

- A multipack is more of the same SKU (6-pack of socks). Stock math is simple: it’s just quantity.

- An assortment is a mixed pack where the exact mix may be fixed or variable (snack box). Variable assortments need extra rules for substitutions.

A bundle should have its own SKU when you need stable reporting and operations. Common reasons:

- You want a dedicated barcode/label for picking and packing.

- You run ads or marketplaces that require a single SKU to buy.

- You need clean sales reporting by bundle (not just by components).

- You plan to change the bundle price often without touching component prices.

Avoid bundling when the “bundle” is really just a temporary discount. If items can be bought separately and the set changes weekly, a promo (discount rule at checkout) keeps your catalog cleaner and reduces inventory surprises.

Pricing math that keeps discounts clear

Customers rarely do deep math. They compare what the bundle costs today against what they think the items would cost on their own. Your job is to make that comparison easy and consistent, so the discount feels real and your pricing rules stay stable.

Start by defining two prices for every bundle:

- List price (reference): sum of current, public prices of the included items (using the specific variants in the bundle).

- Bundle price (what they pay): the actual selling price of the bundle SKU.

Then calculate discount in one standard way and stick to it:

Discount amount = List price - Bundle price

Discount percent = Discount amount / List price

This is the simplest form of product bundle pricing math, and it matches what most shoppers expect.

Rounding is where trust can get lost. If your cart shows $79.99 and “20% off”, customers will check it. Pick rules that avoid awkward pennies.

A practical set of rules:

- Round the bundle price to your normal retail pattern (like ending in .99).

- Compute the discount percent from unrounded values, then display it rounded down to a whole percent.

- If you display “Save $X”, round the savings down to the nearest cent.

- Never show a discount if it is less than a small threshold (for example, under 1%).

Bundles with options need one more choice: do you price from the cheapest possible configuration, or from what the shopper picked? For “choose 1 of 3” kits, calculate list price using the selected variant, not an average, so the displayed savings stays honest.

Finally, decide what happens when component prices change later. The cleanest approach is to treat the bundle price as its own decision: keep it fixed until you intentionally reprice it, and recompute the displayed “compare at” list price from current component prices. If that makes the discount swing too much, set a review trigger (for example, if the discount changes by more than 5 points) so you can adjust before customers notice.

Margin math: make the profit measurable

A bundle discount is only “good” if you can still see the profit. Start by nailing down COGS (cost of goods sold) at the component level. Each item in the kit needs a current unit cost (what you pay to buy or make it), plus any bundle-only costs like extra packaging.

Bundle COGS is simple: add up the component COGS multiplied by the quantities in the bundle, then add packaging and handling.

Bundle COGS = Σ (component unit COGS × component quantity) + packaging + handling

Gross margin $ = bundle price - Bundle COGS - shipping subsidies

Gross margin % = Gross margin $ / bundle price

Example: a “Starter Kit” sells for $99.

- Component A costs $28, Component B costs $12, Component C costs $8.

- The kit includes 1 of each.

- Extra box and inserts cost $3.

- You also cover $6 of shipping as a promotion.

Bundle COGS = 28 + 12 + 8 + 3 = $51

Gross margin $ = 99 - 51 - 6 = $42

Gross margin % = 42 / 99 = 42.4%

That is the core of product bundle pricing math: the discount looks clear to the shopper, and the margin stays visible to you.

For reporting, you may need to allocate bundle revenue back to components (for category sales, commissions, or tax reporting). A common approach is proportional allocation based on each item’s standalone price. If A is 50% of the total standalone value, it gets 50% of bundle revenue. Keep the allocation rule consistent so month-to-month reporting stays comparable.

Before you publish a discount, set guardrails that block bad bundles:

- Minimum gross margin percent for any bundle (for example, 35%)

- Minimum gross margin dollars per order (protects you on low-priced kits)

- Shipping subsidy cap per order (shipping often wipes out “good” margins)

- Include packaging and pick-pack time in COGS for kits that take longer to assemble

Those last costs feel small, but they scale fast. If a kit needs special packing, treat it as real COGS, not a rounding error.

Inventory deduction models that stay accurate

Stop promo stacking surprises

Write down stacking rules once and apply them consistently across web and backend.

If pricing is the promise, inventory is the truth. The moment a bundle sells, your stock system has to answer one question fast: which physical items just left the shelf?

Model A: deduct component inventory at sale time

You keep only components on hand. When the bundle sells, you subtract the required quantities of each component (for example, 1 bottle + 2 filters). This is the cleanest option when the “bundle” is mostly a pricing concept.

It works best when pickers build the kit during fulfillment. It also keeps product bundle pricing math honest, because you can see whether the discount is being “paid for” by cheaper shipping, higher conversion, or just margin.

Model B vs Model C: kit SKU stock or virtual reservation

Model B treats the kit as a real stocked item with its own on-hand count. You assemble kits ahead of time, then deduct 1 kit per sale. You still need a build step that consumes components when you assemble, or your component counts will be wrong.

Model C keeps a virtual bundle SKU for selling and reporting, but reserves components at order time (not shipment time). Reservation prevents overselling when stock is tight or when payment capture is delayed.

Here’s a simple way to choose:

- Need fastest picking and consistent packing? Model B.

- Need the most accurate component-level availability? Model A.

- Need strong oversell protection with backorders or long payment windows? Model C.

- Need clean reporting by bundle SKU without losing component truth? Model C.

- Need minimal warehouse change and flexible swapping? Model A.

Multiple warehouses adds one more rule: deduct where the items actually ship from. With Model A or C, component selection should be warehouse-specific (Warehouse 1 might have the charger, Warehouse 2 might not). With Model B, you must track kit stock per warehouse, and you need transfers or assembly work orders to move kits around.

A quick example: you sell a “Starter Kit” that includes 1 mug and 1 lid. If Warehouse A has mugs but no lids, Model A can still sell only if the order is routed to a warehouse that has both, or if you split-ship (and accept extra shipping cost). Model B avoids that confusion by stocking complete kits where they can actually be shipped.

Step-by-step: model a bundle in your catalog and stock system

A bundle only behaves well if your catalog and inventory agree on what is being sold: a new item, or a set of existing items. Start by deciding what needs to be tracked, priced, and returned.

A simple modeling flow

Use this flow to set up one bundle (and reuse the same rules for the next one):

- Decide whether the bundle gets a separate SKU. Use a bundle SKU if you want separate reporting, a distinct barcode, unique images, or a different return policy. Skip a bundle SKU if it is just a checkout convenience and you only care about component sales.

- Define a bill of materials (BOM). List every component and quantity (including “boring” items like cables, inserts, or batteries). This BOM is the source of truth for inventory deduction.

- Set pricing and discount display rules. Pick one method and stick to it: either (a) show the bundle price with a clear “you save X” versus sum of components, or (b) allocate the discount across components for cleaner margin reporting. This is where product bundle pricing math should be explicit and documented.

- Choose deduction timing. Deduct on order placed if you have fast fulfillment and want to prevent overselling. Deduct on shipped if you take backorders or often edit orders. If you use “reserved stock,” reserve on order placed and deduct on shipment.

- Test edge cases before launch. Try low stock on one component, partial shipments, substitutions, and a return of only part of the kit.

Here’s a quick scenario to validate your setup: you sell a “Starter Kit” with 1 mug and 2 coffee packs. If mugs are out of stock but coffee packs are not, your storefront should either block the bundle or clearly mark it as backordered, and your system should never deduct 2 coffee packs without also reserving the mug.

If you build custom workflows, a tool like Koder.ai can help you define the bundle rules (SKU, BOM, deduction timing) once, then generate the catalog and stock logic consistently across web and backend systems.

Fulfillment, substitutions, and returns without messy math

Bundles get painful the moment reality shows up: one item is missing, the customer wants a swap, or the return is partial. The easiest way to stay sane is to keep the customer-facing order simple (one bundle line) while tracking fulfillment and stock at the component level.

When one component is out of stock, decide up front whether the bundle can ship partial or must wait. If you allow partial shipments, only deduct inventory for what actually ships, and keep the rest reserved so you do not oversell. The bundle line stays “partially fulfilled,” but your stock ledger stays clean.

Allowing substitutions is fine as long as you treat it like a controlled change, not an ad hoc free-for-all. Set substitution rules that preserve reporting and margin.

- Only substitute within a predefined group (same size, type, or cost band).

- Record both the “planned component” and the “shipped component” on the fulfillment.

- Price stays the bundle price unless you explicitly approve an upcharge or credit.

- If the substitute costs more, record the extra cost so bundle margin stays accurate.

Returns need two paths: a full kit return and a single component return. Example: a “Starter Kit” sold for $90 (discounted from $100). It includes a bottle ($40 list) and a brush ($60 list). If the whole kit returns, reverse both components back into stock, and refund $90.

If only the brush returns, refund a prorated share of the paid bundle price, not the brush’s standalone price. A simple, defensible method is to prorate by list price.

- Compute weight: brush share = 60 / (40 + 60) = 60%.

- Refund = $90 x 60% = $54 (plus tax rules as required).

- Restock only the brush, and reverse only its cost in your margin reporting.

This keeps discounts clear, prevents “free money” refunds, and stops inventory from drifting over time.

Common mistakes and traps (and how to avoid them)

Ship bundles with source control

Generate your bundle service and export source code when you are ready to own it.

Bundles usually fail for boring reasons: the catalog rules are unclear, and the math gets applied twice. Fixing it is mostly about choosing one source of truth for price, margin, and stock.

The biggest inventory trap is deducting stock in two places. If you keep a bundle SKU for selling, decide whether it is a “virtual” SKU (no stock of its own) or a “prepacked” SKU (it has its own on-hand units). Virtual bundles should deduct only the components. Prepacked kits should deduct only the kit SKU until you break one open.

Discounts can also look bigger than they are because of rounding. A bundle price like $49.99 feels clean, but if each component is rounded differently, the implied discount may shift by a cent or two per order. Over time that can create customer support noise and messy reporting. Pick a rounding rule and apply it once, at the final bundle price.

Here are common traps that hit margins and operations, with quick fixes:

- You forget “hidden” costs like packaging, pick-and-pack labor, or extra inserts. Add a per-bundle handling cost line so bundle margin calculation stays honest.

- You mix variants (size, color, region) inside a kit without a strict mapping. Require a clear rule: which component SKU is used for each bundle option.

- You update component costs or prices but never recheck the bundle. Schedule a margin review whenever a component changes.

- Your POS or ERP allocates revenue across components differently than your reports. Define one allocation method (by list price share is common) and stick to it.

- Promotions stack accidentally (bundle discount plus coupon plus automatic tier discount). Set stacking rules up front.

If you are building this logic in code, write the rules down before you implement. In Koder.ai, using planning mode for the bundle rules (stock deduction, rounding, discount stacking) can help you keep the behavior consistent when you later export source code or add new bundles.

Quick checklist before you launch a bundle

Before you publish a bundle, take 10 minutes to confirm the rules are consistent. Most problems show up later as “why did we lose money?” or “why is stock wrong?” and both usually trace back to unclear math.

Start with the customer-facing price. If you show “Save 15%”, make sure the number is based on the same reference price you use everywhere else (your current selling prices, not an old MSRP). This is where product bundle pricing math gets tested in real life: the displayed discount should match what a shopper can verify.

Then check profit using the exact costs that will hit you on every order. Include pick-and-pack labor, packaging, payment fees, and any extra shipping cost caused by heavier or multiple items. If the bundle only clears your margin target when everything goes perfectly, it is a risky offer.

Inventory is the other half. Decide whether the bundle is its own SKU, how it deducts components, and what happens in edge cases like cancellations and returns. If you cannot explain the stock logic in one sentence, it will fail under pressure.

Here’s a tight pre-launch checklist to run through:

- Discount proof: the “you save” message and the checkout total use the same reference prices and rounding rules.

- Margin proof: bundle profit stays above your minimum after product cost, fees, packaging, and fulfillment work.

- Stock proof: selling one bundle always deducts the same component quantities, and returns/cancels reverse them cleanly.

- Low-stock rule: define one behavior (block sale, allow backorder, or offer a defined substitute) and apply it consistently.

- Reporting proof: you can answer, without manual spreadsheets, how many bundles sold, how many components were consumed, and profit per bundle.

If you are automating this in a tool like Koder.ai, write these rules down first, then implement them exactly as written so the numbers stay stable as you scale.

Example: a starter kit with real numbers

Change bundle logic safely

Iterate on pricing and stock logic safely with snapshots and rollback.

Picture a “Starter Kit” made of three items you also sell separately. The goal is to make the discount obvious, the profit easy to check, and stock always correct.

The kit, prices, and discount

Assume these components, with simple pricing and cost (COGS):

- Water bottle: list price $20, COGS $8

- Gym towel: list price $12, COGS $4

- Protein shaker: list price $18, COGS $6

If sold separately, the customer would pay $20 + $12 + $18 = $50 (that is your “sum of parts” list total).

Now set the bundle price to $42. The discount is $50 - $42 = $8 off. Discount percent is $8 / $50 = 16%.

This is the cleanest way to present product bundle pricing math: show the sum of parts, then show the kit price and the savings.

COGS and margin on the bundle

Bundle COGS is just the sum of component COGS: $8 + $4 + $6 = $18.

Gross profit on the kit is $42 - $18 = $24.

Gross margin percent is $24 / $42 = 57.1%.

That one number lets you compare the bundle to your normal margins. If your usual target is 60%, you know this kit is slightly tighter and you can decide if the higher conversion rate is worth it.

Inventory impact (5 kits sold, then a partial return)

Start with on-hand inventory: bottles 40, towels 30, shakers 25.

Sell 5 kits. Inventory should deduct 5 units of each component:

Bottles 40 - 5 = 35, towels 30 - 5 = 25, shakers 25 - 5 = 20.

Now a customer returns only the towel from one kit. Put 1 towel back into stock (towels 25 + 1 = 26).

For the money side, pick a clear rule and stick to it: either (a) no partial returns on kits, or (b) partial refunds use each item’s share of the kit price, not the full standalone price. If you refund using the standalone towel price ($12), you can accidentally turn a profitable kit into a loss.

Next steps: document the rules and automate what you can

Bundles only stay profitable and accurate when everyone follows the same rules. Before you scale a kit across channels, write down a simple “bundle policy” that your team can point to when something goes weird.

Include three things in plain language: how you set bundle prices (and how discounts are shown), how inventory is deducted (bundle SKU, components, or both), and how returns work (refund on the bundle or on each component).

A good policy can fit on one page. Use a short checklist like this:

- Pricing rule: what discount is allowed and where it is displayed (percent off, fixed price, or “buy X get Y”).

- Margin rule: what cost basis you use and the minimum margin you will accept.

- Inventory rule: what gets deducted at order time and what happens if a component is out of stock.

- Returns rule: full kit only vs partial returns, and how you handle opened or missing items.

- Change rule: who can edit bundle composition, prices, and substitutions.

Next, test the edge cases with real orders, not spreadsheets. Create one test order for each scenario you expect: a partial return, a substitution, a backordered component, a bundle with mixed tax categories, and a price change mid-month. Save screenshots or notes so you can repeat the test after system updates.

Set a monthly review to catch margin drift. Component costs change quietly, and your “great deal” can become a loss leader without anyone noticing. A 15-minute calendar reminder to review top bundles, component costs, and actual margins is usually enough.

If your current tools cannot express your rules cleanly, build a small internal app that does just what you need (bundle setup, validation, and reporting). With Koder.ai, you can describe your bundle rules in chat and generate a back-office tool (React + Go + PostgreSQL), then iterate safely using snapshots and rollback when you need to adjust logic.