Nov 05, 2025·8 min

Charles Geschke and Adobe’s Legacy: The Infrastructure Behind PDF

Explore Charles Geschke’s role in Adobe’s engineering legacy and the infrastructure behind PDFs—standards, rendering, fonts, security, and why it works everywhere.

Explore Charles Geschke’s role in Adobe’s engineering legacy and the infrastructure behind PDFs—standards, rendering, fonts, security, and why it works everywhere.

If you’ve ever opened a PDF that looked identical on a phone, a Windows laptop, and a printer at the copy shop, you’ve benefited from Charles Geschke’s work—even if you’ve never heard his name.

Geschke co-founded Adobe and helped drive early technical decisions that made digital documents reliable: not just “a file you can send,” but a format that preserves layout, fonts, and graphics with predictable results. That reliability is the quiet convenience behind everyday moments like signing a lease, submitting a tax form, printing a boarding pass, or sharing a report with clients.

An engineering legacy is rarely a single invention. More often, it’s durable infrastructure that others can build on:

In document formats, that legacy shows up as fewer surprises: fewer broken line breaks, swapped fonts, or “it looked fine on my machine” moments.

This isn’t a full biography of Geschke. It’s a practical tour of the PDF infrastructure and the engineering concepts beneath it—how we got dependable document exchange at global scale.

You’ll see how PostScript set the stage, why PDF became a shared language, and how rendering, fonts, color, security, accessibility, and ISO standardization fit together.

It’s written for product teams, operations leaders, designers, compliance folks, and anyone who relies on documents to “just work”—without needing to be an engineer.

Before PDF, “sending a document” often meant sending a suggestion of what the document should look like.

You could design a report on your office computer, print it perfectly, and then watch it fall apart when a colleague opened it elsewhere. Even within the same company, different computers, printers, and software versions could produce noticeably different results.

The most common failures were surprisingly ordinary:

The result was friction: extra rounds of “What version are you using?”, re-exporting files, and printing test pages. The document became a source of uncertainty instead of a shared reference.

A device-independent document carries its own instructions for how it should appear—so it doesn’t rely on the quirks of the viewer’s computer or printer.

Instead of saying “use whatever fonts and defaults you have,” it describes the page precisely: where text goes, how fonts should render, how images should scale, and how each page should print. The goal is simple: the same pages, everywhere.

Businesses and governments didn’t just want nicer formatting—they needed predictable outcomes.

Contracts, compliance filings, medical records, manuals, and tax forms depend on stable pagination and consistent appearance. When a document is evidence, an instruction, or a binding agreement, “close enough” isn’t acceptable. That pressure for dependable, repeatable documents set the stage for formats and technologies that could travel across devices without changing shape.

PostScript is one of those inventions you rarely name, yet you benefit from it any time a document prints correctly. Co-created under Adobe’s early leadership (with Charles Geschke as a key figure), it was designed for a very specific problem: how to tell a printer exactly what a page should look like—text, shapes, images, spacing—without depending on the quirks of a particular machine.

Before PostScript-style thinking, many systems treated output like pixels: you “drew” dots onto a screen-sized grid and hoped the same bitmap would work elsewhere. That approach breaks quickly when the destination changes. A 72 DPI monitor and a 600 DPI printer don’t share the same idea of a pixel, so a pixel-based document can look blurry, reflow oddly, or clip at the margins.

PostScript flipped the model: instead of sending pixels, you describe the page using instructions—place this text at these coordinates, draw this curve, fill this area with this color. The printer (or interpreter) renders those instructions at whatever resolution it has available.

In publishing, “close enough” isn’t enough. Layout, typography, and spacing need to match proofs and press output. PostScript aligned perfectly with that demand: it supported precise geometry, scalable text, and predictable placement, which made it a natural fit for professional printing workflows.

By proving that “describe the page” can produce consistent results across devices, PostScript established the core promise later associated with PDF: a document that keeps its visual intent when shared, printed, or archived—no matter where it’s opened.

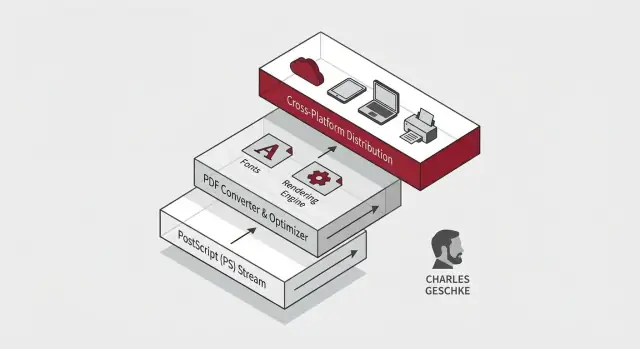

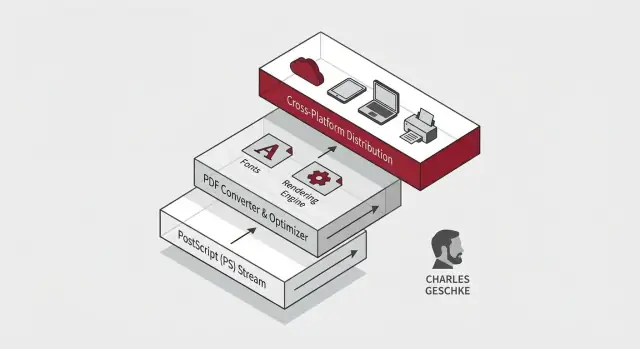

PostScript solved a big problem: it let printers render a page from precise drawing instructions. But PostScript was primarily a language for producing pages, not a tidy file format for storing, sharing, and revisiting documents.

PDF took the same “page description” idea and turned it into a portable document model: a file you can hand to someone else and expect it to look the same—on another computer, another operating system, or years later.

At a practical level, a PDF is a container that bundles everything needed to reproduce pages consistently:

This packaging is the key shift: instead of relying on the receiving device to “have the same stuff installed,” the document can carry its own dependencies.

PDF and PostScript share DNA: both describe pages in a device-independent way. The difference is intent.

Acrobat became the toolchain around that promise. It’s used to create PDFs from other documents, view them consistently, edit when needed, and validate that files match standards (for example, long-term archiving profiles). That ecosystem is what turned a clever file format into a day-to-day workflow for billions.

When people say “it’s a PDF, it will look the same,” they’re really praising a rendering engine: the part of software that turns a file’s instructions into pixels on a screen or ink on paper.

A typical renderer follows a predictable sequence:

That sounds straightforward until you remember that every step hides edge cases.

PDF pages mix features that behave differently across devices:

Different operating systems and printers ship with different font libraries, graphics stacks, and drivers. A conforming PDF renderer reduces surprises by strictly following the spec—and by honoring embedded resources rather than “guessing” with local substitutes.

Ever noticed how a PDF invoice prints with the same margins and page count from different computers? That reliability comes from deterministic rendering: the same layout decisions, the same font outlines, the same color conversions—so “Page 2 of 2” doesn’t become “Page 2 of 3” when it hits the printer queue.

Fonts are the quiet troublemakers of document consistency. Two files can contain the “same text,” yet look different because the font isn’t actually the same on every device. If a computer doesn’t have the font you used, it substitutes another one—changing line breaks, spacing, and sometimes even which characters appear.

Fonts affect far more than style. They define exact character widths, kerning (how letters fit together), and metrics that determine where every line ends. Swap one font for another and a carefully aligned table can shift, pages can reflow, and a signature line can land on the next page.

That’s why early “send a document to someone else” workflows often failed: word processors relied on local font installs, and printers had their own font sets.

PDF’s approach is straightforward: include what you need.

Example: a 20-page contract using a commercial font might embed only the glyphs needed for names, numbers, punctuation, and “§”. That can be a few hundred glyphs instead of thousands.

Internationalization isn’t just “supports many languages.” It means the PDF must reliably map each character you see (like “Ж”, “你”, or “€” ) to the right shape in the embedded font.

A common failure mode is when text looks correct but is stored with the wrong mapping—copy/paste breaks, search fails, or screen readers read gibberish. Good PDFs preserve both: the visual glyphs and the underlying character meaning.

Not every font can legally be embedded, and not every platform ships the same fonts. These constraints pushed PDF engineering toward flexible strategies: embed when allowed, subset to reduce distribution risk and file size, and provide fallbacks that don’t silently change meaning. This is also why “use standard fonts” became a best practice in many organizations—because licensing and availability directly impact whether “looks the same” is even possible.

PDFs feel “solid” because they can preserve both pixel-based images (like photos) and resolution-independent vector graphics (like logos, charts, and CAD drawings) in one container.

When you zoom a PDF, photos behave like photos: they’ll eventually show pixels because they’re made of a fixed grid. But vector elements—paths, shapes, and text—are described mathematically. That’s why a logo or a line chart can stay crisp at 100%, 400%, or on a poster-sized print.

A well-made PDF mixes these two types carefully, so diagrams stay sharp while images remain faithful.

Two PDFs can look similar yet have very different sizes. Common reasons:

This is why “Save as PDF” from different tools produces wildly different results.

Screens use RGB (light-based mixing). Printing often uses CMYK (ink-based mixing). Converting between them can shift brightness and saturation—especially with vivid blues, greens, and brand colors.

PDF supports color profiles (ICC profiles) to describe how colors should be interpreted. When profiles are present and respected, what you approve on screen is much closer to what arrives from the printer.

Color and image issues usually trace back to missing or ignored profiles, or inconsistent export settings. Typical failures include:

Teams that care about brand and print quality should treat PDF export settings as part of the deliverable, not an afterthought.

PDF succeeded not just because the format was clever, but because people could trust it across companies, devices, and decades. That trust is what standardization provides: a shared rulebook that lets different tools produce and read the same file without negotiating private details.

Without a standard, each vendor can interpret “PDF” slightly differently—font handling here, transparency there, encryption somewhere else. The result is familiar: a file that looks fine in one viewer but breaks in another.

A formal standard tightens the contract. It defines what a valid PDF is, which features exist, and how they must behave. That makes interoperability practical at scale: a bank can send statements, a court can publish filings, and a printer can output a brochure, all without coordinating which app the recipient uses.

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) publishes specifications that many industries treat as neutral ground. When PDF became an ISO standard (ISO 32000), it moved from “an Adobe format” to “a public, documented, consensus-based specification.”

This shift matters for long time horizons. If a company disappears or changes direction, the ISO text remains, and software can still be built to the same rules.

PDF isn’t one-size-fits-all, so ISO also defines profiles—focused versions of PDF for specific jobs:

Standards reduce “it worked on my machine” moments by limiting ambiguity. They also make procurement easier: organizations can ask for “PDF/A” or “PDF/UA” support and know what that claim should mean—even when different vendors implement it.

PDFs earned trust because they travel well—but that same portability makes security a shared responsibility between the file creator, the tools, and the reader.

People often lump everything into “password-protected PDFs,” but PDF security has a few different layers:

In other words, permissions can reduce casual misuse, but they aren’t a substitute for encryption or access control.

A digital signature can prove two valuable things: who signed (identity, depending on the certificate) and what changed (tamper detection). If a signed PDF is altered, readers can show the signature as invalid.

What signatures don’t prove: that the content is true, fair, or approved by your organization’s policies. They confirm integrity and signer identity—not correctness.

Most real-world issues aren’t about “breaking PDF encryption.” They’re about unsafe handling:

For individuals: keep your PDF reader updated, avoid opening unexpected attachments, and prefer files shared via a trusted system rather than forwarded copies.

For teams: standardize on approved viewers, disable risky features where possible (like automatic script execution), scan inbound documents, and train staff on safe sharing. If you publish “official” PDFs, sign them and document verification steps in internal guidance (or a simple page like /security).

Accessibility isn’t a “polish step” for PDFs—it’s part of the same infrastructure promise that made PDF valuable in the first place: the document should work reliably for everyone, on any device, with any assistive technology.

A PDF can look perfect and still be unusable to someone who relies on a screen reader. The difference is structure. A tagged PDF includes a hidden map of the content:

Many accessibility problems come from “visual-only” documents:

These aren’t edge cases—they directly affect customers, employees, and citizens trying to complete basic tasks.

Remediation is costly because it reconstructs structure after the fact. It’s cheaper to build access in from the source:

Treat accessibility as a requirement in your document workflow, not a final review item.

A “software standard used by billions” isn’t just about popularity—it’s about predictability. A PDF might be opened on a phone, previewed in an email app, annotated in a desktop reader, printed from a browser, and archived in a records system. If the document changes meaning anywhere along that path, the standard is failing.

PDFs live inside many “good enough” viewers: OS preview tools, browser viewers, office suites, mobile apps, printer firmware, and enterprise document management systems. Each one implements the spec with slightly different priorities—speed on low-power devices, limited memory, security restrictions, or simplified rendering.

That diversity is a feature and a risk. It’s a feature because PDFs remain usable without a single gatekeeper. It’s a risk because differences show up in the cracks: transparency flattening, font substitution, overprint behavior, form field scripting, or embedded color profiles.

When a format is universal, rare bugs become common. If 0.1% of PDFs trigger a rendering quirk, that’s still millions of documents.

Interoperability testing is how the ecosystem stays sane: creating “torture tests” for fonts, annotations, printing, encryption, and accessibility tagging; comparing outputs across engines; and fixing ambiguous interpretations of the spec. This is also why conservative authoring practices (embed fonts, avoid exotic features unless needed) remain valuable.

Interoperability isn’t a nice-to-have—it’s infrastructure. Governments rely on consistent forms and long retention periods. Contracts depend on pagination and signatures staying stable. Academic publishing needs faithful typography and figures across submission systems. Archival profiles such as PDF/A exist because “open later” must mean “open the same way later.”

The ecosystem effect is simple: the more places a PDF can travel unchanged, the more organizations can trust documents as durable, portable evidence.

PDF succeeded because it optimized for a deceptively simple promise: a document should look and behave the same wherever it’s opened. Teams can borrow that mindset even if you’re not building file formats.

When deciding between open standards, vendor formats, or internal schemas, start by listing the promises you need to keep:

If those promises matter, prefer formats with ISO standards, multiple independent implementations, and clear profiles (for example, archival variants).

Use this as a lightweight policy template:

Many teams end up turning “PDF reliability” into a product feature: portals that generate invoices, systems that assemble compliance packets, or workflows that collect signatures and archive artifacts.

If you want to prototype or ship those document-heavy systems faster, Koder.ai can help you build the surrounding web app and backend from a simple chat—use planning mode to map the workflow, generate a React frontend with a Go + PostgreSQL backend, and iterate safely with snapshots and rollback. When you’re ready, you can export the source code or deploy with hosting and custom domains.

An engineering legacy is the durable infrastructure that makes other people’s work predictable: clear specs, stable core models, and tools that interoperate across vendors.

In PDFs, that shows up as fewer “it looked different on my machine” problems—consistent pagination, embedded resources, and long-term readability.

Before PDF, documents often depended on local fonts, app defaults, printer drivers, and OS-specific rendering. When any of those differed, you’d see reflowed text, shifted margins, missing characters, or changed page counts.

PDF’s value proposition was bundling enough information (fonts, graphics instructions, metadata) to reproduce pages reliably across environments.

PostScript is primarily a page description language aimed at generating printed output: it tells a device how to draw a page.

PDF takes the same “describe the page” idea but packages it as a structured, self-contained document optimized for viewing, exchange, search, linking, and archiving—so you can open the same file later and get the same pages.

Rendering means converting the PDF’s instructions into pixels on a screen or marks on paper. Small interpretation differences—fonts, transparency, color profiles, stroke rules—can change what you see.

A conforming renderer follows the spec closely and honors embedded resources, which is why invoices, forms, and reports tend to keep identical margins and page counts across devices.

Fonts control exact character widths and spacing. If a viewer substitutes a different font, line breaks and pagination can change—even if the text content is identical.

Embedding (often with subsetting) puts the required font data inside the PDF so recipients don’t depend on what’s installed locally.

A PDF can display the right glyphs but still store incorrect character mappings, which breaks search, copy/paste, and screen readers.

To avoid this, generate PDFs from sources that preserve text semantics, embed appropriate fonts, and validate that the document’s text layer and character encoding are correct—especially for non-Latin scripts.

Screens are typically RGB; print workflows often use CMYK. Converting between them can shift brightness and saturation, especially for vivid brand colors.

Use consistent export settings and include ICC profiles when color accuracy matters. Avoid last-minute conversions and watch for “double-compressed” images that introduce artifacts.

ISO standardization (ISO 32000) turns PDF from a vendor-controlled format into a public, consensus-based specification.

That makes long-term interoperability more realistic: multiple independent tools can implement the same rules, and organizations can rely on a stable standard even as software vendors change.

They’re constrained profiles for specific outcomes:

Pick the profile that matches your operational requirement—archive, print, or accessibility compliance.

Encryption controls who can open the file; “permissions” like no-copy/no-print are policy hints that compliant software may enforce, but they’re not strong security by themselves.

Digital signatures help prove integrity (detect tampering) and, depending on certificates, the signer’s identity—but they don’t prove the content is accurate or approved. For real-world safety: keep readers updated, treat inbound PDFs as untrusted, and standardize verification steps for official documents.