Oct 22, 2025·8 min

How to Choose the Right Backend Programming Language in 2026

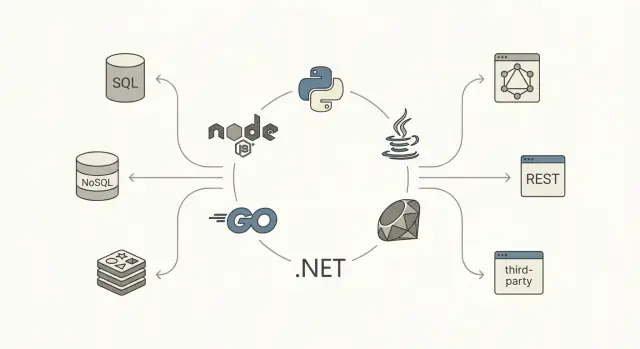

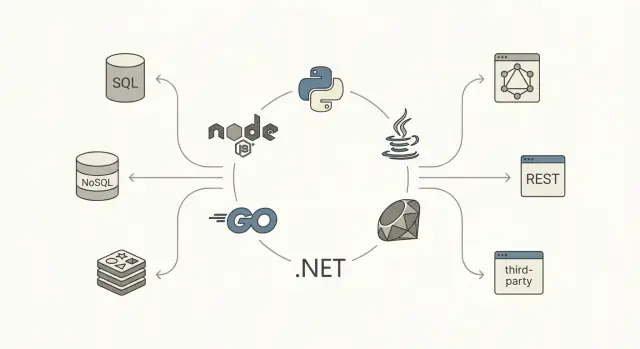

Compare Node.js, Python, Java, Go, .NET, and Ruby for backend work. Learn trade-offs in performance, hiring, tooling, scaling, and long-term maintenance.

Compare Node.js, Python, Java, Go, .NET, and Ruby for backend work. Learn trade-offs in performance, hiring, tooling, scaling, and long-term maintenance.

“Best backend language” is usually shorthand for “best fit for what I’m building, with the people and constraints I have.” A language can be perfect for one backend workload and a poor match for another—even if it’s popular, fast, or loved by your team.

Before you compare Node.js backend vs Python backend vs Java backend (and so on), name the job your backend must do:

Different goals shift the weighting between performance vs productivity. A language that accelerates feature delivery for a CRUD API might slow you down for high-throughput streaming or low-latency systems.

Choosing a backend programming language is often decided by constraints more than features:

There is no single best backend language in 2026—only trade-offs. Ruby on Rails might win for speed of building a product, Go might win for operational simplicity, Java might win for mature ecosystems and enterprise tooling, and Node.js might win for real-time and full-stack JavaScript alignment.

By the end of this guide, you should be able to pick a language with confidence by matching it to your workload, constraints, and long-term ownership—not by hype or rankings.

Picking a backend programming language is less about “what’s best” and more about what optimizes your specific outcomes. Before you compare a Node.js backend to a Python backend, or Java backend to Go backend, make the criteria explicit—otherwise you’ll debate preferences instead of making a decision.

Start with a short list you can actually score:

Add any domain-specific requirements (e.g., real-time features, heavy data processing, or strict compliance) as additional criteria.

TCO is the combined price of building and owning the system:

A language that’s fast to prototype can become expensive if it leads to frequent incidents or hard-to-change code.

Some constraints are non-negotiable, and it’s better to surface them early:

Don’t treat every criterion equally. If you’re validating a market, weight time-to-market higher. If you’re building a long-lived internal platform, weight maintainability and operational stability more. A simple weighted scorecard keeps the conversation grounded and makes trade-offs explicit for API development and beyond.

Before you compare syntax or benchmarks, write down what your backend must do and how it will be shaped. Languages look “best” when they match the workload and the architecture you’re actually building.

Most backends are a mix, but the dominant work matters:

If your system is mostly I/O-bound, concurrency primitives, async tooling, and ergonomics often matter more than raw speed. If it’s CPU-bound, predictable performance and easy parallelism rise to the top.

Traffic shape changes language pressure:

Also note global latency expectations and the SLA you’re targeting. A 99.9% API SLA with tight p95 latency requirements pushes you toward mature runtimes, strong tooling, and proven deployment patterns.

Document your data path:

Finally, list integrations: third-party APIs, messaging/queues (Kafka, RabbitMQ, SQS), and background jobs. If async work and queue consumers are central, pick a language/ecosystem where workers, retries, idempotency patterns, and monitoring are first-class—not afterthoughts.

Performance isn’t a single number. For backends, it usually breaks down into latency (how fast one request completes), throughput (how many requests you can serve per second), and resource usage (CPU, memory, and sometimes network/IO). The language and runtime affect all three—mostly through how they schedule work, manage memory, and handle blocking operations.

A language that looks fast in microbenchmarks can still produce poor tail latency (p95/p99) under load—often due to contention, blocking calls, or memory pressure. If your service is IO-heavy (DB, cache, HTTP calls), the biggest wins often come from reducing waiting and improving concurrency, not from shaving nanoseconds off pure compute.

Different ecosystems push different approaches:

GC-managed runtimes can boost developer productivity, but allocation rate and heap growth can impact tail latency via pauses or increased CPU work for collection. You don’t need to be a GC expert—just know that “more allocations” and “bigger objects” can become performance problems, especially at scale.

Before deciding, implement (or prototype) a few representative endpoints and measure:

Treat this as an engineering experiment, not a guess. Your workload’s mix of IO, compute, and concurrency will make the “fastest” backend programming language look different in practice.

A backend language rarely succeeds on syntax alone. The day-to-day experience is shaped by its ecosystem: how quickly you can scaffold services, evolve schemas, secure endpoints, test changes, and ship safely.

Look for frameworks that match your preferred style (minimal vs batteries-included) and your architecture (monolith, modular monolith, microservices). A healthy ecosystem usually has at least one widely adopted “default” option plus solid alternatives.

Pay attention to the unglamorous parts: mature ORMs or query builders, reliable migrations, authentication/authorization libraries, input validation, and background job tooling. If these pieces are fragmented or outdated, teams tend to re-implement basics and accumulate inconsistent patterns across services.

The best package manager is the one your team can operate predictably. Evaluate:

Also check the language and framework release cadence. Fast releases can be great—if your organization can keep up. If you’re in a regulated environment or run many services, a slower, long-term-support rhythm may reduce operational risk.

Modern backends need first-class observability. Ensure the ecosystem has mature options for structured logging, metrics (Prometheus/OpenTelemetry), distributed tracing, and profiling.

A practical test: can you go from “p95 latency spiked” to a specific endpoint, query, or dependency call within minutes? Languages with strong profiling and tracing integrations can save significant engineering time over a year.

Operational constraints should influence language choice. Some runtimes shine in containers with small images and fast startup; others excel for long-running services with predictable memory behavior. If serverless is on the table, cold-start characteristics, packaging limits, and connection management patterns matter.

Before committing, build a thin vertical slice and deploy it the way you intend to run it (e.g., in Kubernetes or a function platform). It’s often more revealing than reading framework feature lists.

Maintainability is less about “beautiful code” and more about how quickly a team can change behavior without breaking production. Language choice influences that through type systems, tooling, and the norms of the ecosystem.

Strongly typed languages (Java, Go, C#/.NET) tend to make large refactors safer because the compiler becomes a second reviewer. Rename a field, change a function signature, or split a module, and you get immediate feedback across the codebase.

Dynamically typed languages (Python, Ruby, vanilla JavaScript) can be very productive, but correctness relies more on conventions, test coverage, and runtime checks. If you go this route, “gradual typing” often helps: TypeScript for Node.js, or type hints plus a checker (e.g., mypy/pyright) for Python. The key is consistency—half-typed code can be worse than either extreme.

Backend systems fail at the boundaries: request/response formats, event payloads, and database mappings. A maintainable stack makes contracts explicit.

OpenAPI/Swagger is the common baseline for HTTP APIs. Many teams pair it with schema validation and DTOs to prevent “stringly-typed” APIs. Examples you’ll see in practice:

Code generation support matters: generating clients/servers/DTOs reduces drift and improves onboarding.

Ecosystems differ in how naturally testing fits into the workflow. Node commonly uses Jest/Vitest with fast feedback. Python’s pytest is expressive and excels at fixtures. Java’s JUnit/Testcontainers is strong for integration tests. Go’s built-in testing package encourages straightforward tests, while .NET’s xUnit/NUnit integrates tightly with IDEs and CI. Ruby’s RSpec culture is opinionated and readable.

A practical rule: choose the ecosystem where it’s easiest for your team to run tests locally, mock dependencies cleanly, and write integration tests without ceremony.

Picking a backend programming language is also a staffing decision. A language that’s “best” on paper can become expensive if you can’t hire, onboard, and retain people who can operate it confidently.

Inventory current strengths: not just who can write code, but who can debug production issues, tune performance, set up CI, handle incidents, and review PRs at speed.

A simple rule that holds up well: prefer languages the team can operate well, not just write. If your on-call rotation already struggles with observability, deployments, or concurrency bugs, adding a new runtime or paradigm may amplify risk.

Hiring markets vary sharply by geography and experience level. For example, you may find plenty of junior Node.js or Python candidates locally, but fewer senior engineers with deep JVM tuning or Go concurrency experience—or the opposite, depending on your region.

When evaluating “availability,” look at:

Even strong engineers need time to become effective in a new ecosystem: idioms, frameworks, testing practices, dependency management, and deployment tooling. Estimate onboarding in weeks, not days.

Practical questions:

Optimizing for initial velocity can backfire if the team dislikes maintaining the stack. Consider upgrade cadence, framework churn, and how pleasant the language is for writing tests, refactoring, and tracing bugs.

If you expect turnover, prioritize readability, predictable tooling, and a deep bench of maintainers—because “ownership” lasts longer than the first release.

Node.js shines for I/O-heavy APIs, chat, collaboration tools, and real-time features (WebSockets, streaming). A common stack is TypeScript + Express/Fastify/NestJS, often paired with PostgreSQL/Redis and queues.

The usual pitfalls are CPU-bound work blocking the event loop, dependency sprawl, and inconsistent typing if you stay on plain JavaScript. When performance matters, push heavy compute to workers/services and keep strict TypeScript + linting.

Python is a productivity leader, especially for data-heavy backends that touch analytics, ML, ETL, and automation. Framework choices typically split between Django (batteries-included) and FastAPI (modern, typed, API-first).

Performance is usually “good enough” for many CRUD systems, but hot paths can become costly at scale. Common strategies: async I/O for concurrency, caching, moving compute to specialized services, or using faster runtimes/extensions where justified.

Java remains a strong default for enterprise systems: mature JVM tooling, predictable performance, and a deep ecosystem (Spring Boot, Quarkus, Kafka, observability tooling). Ops maturity is a key advantage—teams know how to deploy and run it.

Typical use cases include high-throughput APIs, complex domains, and regulated environments where stability and long-term support matter.

Go fits microservices and network services where concurrency and simplicity are priorities. Goroutines make “many things at once” straightforward, and the standard library is practical.

Trade-offs: fewer batteries-included web frameworks than Java/.NET, and you may write more plumbing yourself (though that can be a feature).

Modern .NET (ASP.NET Core) is excellent for enterprise APIs, with strong tooling (Visual Studio, Rider), great performance, and solid Windows/Linux parity. A common stack is ASP.NET Core + EF Core + SQL Server/PostgreSQL.

Ruby on Rails is still one of the fastest ways to ship a polished web product. Scaling is often achieved by extracting heavy workloads into background jobs and services.

The trade-off is raw throughput per instance; you typically scale horizontally and invest earlier in caching and job queues.

There’s rarely a single “best” backend programming language—only a best fit for a specific workload, team, and risk profile. Here are common patterns and the languages that tend to match them.

If speed of iteration and hiring generalists matter most, Node.js and Python are frequent picks. Node.js shines when the same team wants to share TypeScript across frontend and backend, and when API development is primarily I/O-bound. Python is strong for data-heavy products, scripting, and teams that expect to integrate analytics or ML early.

Ruby on Rails is still a great “feature factory” when the team is Rails-experienced and you’re building a conventional web app with lots of CRUD and admin workflows.

For services where latency, throughput, and predictable resource use dominate, Go is a common default: fast startup, simple concurrency model, and easy containerization. Java and .NET are also excellent choices here, especially when you need mature profiling, JVM/CLR tuning, and battle-tested libraries for distributed systems.

If you expect long-running connections (streaming, websockets) or high fan-out, prioritize runtime behavior under load and operational tooling over raw micro-benchmarks.

For internal tools, developer time often costs more than compute. Python, Node.js, and .NET (particularly in Microsoft-heavy orgs) typically win due to rapid delivery, strong libraries, and easy integration with existing systems.

In compliance-heavy settings (auditability, access controls, long support cycles), Java and .NET tend to be safest: mature security practices, established governance patterns, and predictable LTS options. This matters when “Who can approve a dependency?” is as important as performance vs productivity.

A monolith usually benefits from a single primary language to keep onboarding and maintenance simple. Microservices can justify more diversity—but only when teams are truly autonomous and platform tooling (CI/CD, observability, standards) is strong.

A pragmatic split is common: e.g., Java/.NET/Go for core APIs and Python for data pipelines. Avoid polyglot “for preference” early; each new language multiplies incident response, security review, and ownership overhead.

Picking a backend programming language is easier when you treat it like a product decision: define constraints, score options, then validate with a small proof-of-concept (PoC). The goal isn’t a “perfect” choice—it’s a defensible one you can explain to your team and future hires.

Start with two lists:

If a language fails a must-have, it’s out—no scoring debate. This prevents analysis paralysis.

Create a short matrix and keep it consistent across candidates.

| Criterion | Weight (%) | Score (1–5) | Weighted score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance & concurrency fit | 20 | ||

| Ecosystem & libraries (DB, auth, queues) | 20 | ||

| Developer productivity | 15 | ||

| Hiring & long-term maintainability | 15 | ||

| Operational fit (deploy, observability) | 15 | ||

| Safety & correctness (typing, tooling) | 15 |

How to calculate: Weighted score = Weight × Score. Sum totals per language. Keep weights to ~5–7 criteria so the numbers stay meaningful.

PoC checklist (time-box it to 1–3 days per language):

Decide upfront what “good” means:

Score the PoC results back into the matrix, then choose the option with the best total and the fewest must-have risks.

Choosing a backend programming language is easiest to get wrong when the decision is made from the outside in—what’s trending, what a conference talk praised, or what won a single benchmark.

A micro-benchmark rarely reflects your real bottlenecks: database queries, third‑party APIs, serialization, or network latency. Treat “fastest” claims as a starting question, not a verdict. Validate with a thin proof-of-concept that mirrors your workload: data access patterns, payload sizes, and concurrency profile.

Many teams pick a language that looks productive in code, then pay the price in production:

If your org can’t support the operational model, the language choice won’t save you.

Future-proofing often means not betting everything at once. Favor incremental migration:

It means best fit for your workload, team, and constraints, not a universal winner. A language can be great for a CRUD API and a poor fit for low-latency streaming or CPU-heavy processing. Make the choice based on measurable needs (latency, throughput, ops, hiring), not rankings.

Start by writing down the dominant workload:

Then pick languages whose concurrency model and ecosystem match that workload, and validate with a small PoC.

Use a short, scoreable list:

Add any hard requirements like compliance, serverless constraints, or required SDKs.

TCO includes building and owning the system:

A language that prototypes quickly can still be expensive if it increases incidents or makes changes risky.

Concurrency determines how well your service handles many simultaneous requests and long waits on DB/HTTP/queues:

Because what hurts in production is often tail latency (p95/p99), not average speed. GC-managed runtimes can see latency spikes if allocation rate and heap growth are high. The practical approach is to measure your real critical paths and watch CPU/memory under load, rather than trusting microbenchmarks.

Do a thin vertical slice that matches real work:

Time-box it (1–3 days per language) and compare results against pre-set targets.

It depends on how you want correctness enforced:

If you choose a dynamic language, use gradual typing consistently (e.g., TypeScript or Python type hints + mypy/pyright) to avoid “half-typed” drift.

Because production ownership is as important as writing code. Ask:

Prefer the language your team can operate well, not just implement features in.

Common pitfalls:

Future-proof by keeping contracts explicit (OpenAPI/JSON Schema/Protobuf), validating with PoCs, and migrating incrementally (e.g., strangler pattern) instead of rewriting everything at once.

Match the model to your dominant workload and your team’s operational maturity.