Aug 18, 2025·8 min

Chris Lattner’s LLVM: The Quiet Engine Behind Modern Toolchains

Learn how Chris Lattner’s LLVM became the modular compiler platform behind languages and tools—powering optimizations, better diagnostics, and fast builds.

What LLVM Is, in Plain English

LLVM is best thought of as the “engine room” that many compilers and developer tools share.

When you write code in a language like C, Swift, or Rust, something has to translate that code into instructions your CPU can run. A traditional compiler often built every part of that pipeline itself. LLVM takes a different approach: it provides a high-quality, reusable core that handles the hard, expensive parts—optimization, analysis, and generating machine code for many kinds of processors.

A shared foundation for many languages

LLVM isn’t a single compiler you “use directly” most of the time. It’s compiler infrastructure: building blocks that language teams can assemble into a toolchain. One team can focus on syntax, semantics, and developer-facing features, then hand off the heavy lifting to LLVM.

That shared foundation is a big reason modern languages can ship fast, safe toolchains without reinventing decades of compiler work.

Why it matters even if you’re not a compiler person

LLVM shows up in day-to-day developer experience:

- Speed: it can turn high-level code into efficient machine code across platforms.

- Better errors and debugging: the ecosystem around LLVM enables richer diagnostics and better tooling.

- More than “just compilation”: static analysis, sanitizers, code coverage, and other developer aids often build on the same underlying representation and libraries.

What this article will (and won’t) be

This is a guided tour of the ideas Chris Lattner set in motion: how LLVM is structured, why the middle layer matters, and how it enables optimizations and multi-platform support. It’s not a textbook—we’ll keep the focus on intuition and real-world impact rather than formal theory.

Chris Lattner’s Original Vision

Chris Lattner is a computer scientist and engineer who, as a graduate student in the early 2000s, started LLVM with a practical frustration: compiler technology was powerful, but hard to reuse. If you wanted a new programming language, better optimizations, or support for a new CPU, you often had to tinker with a tightly coupled “all-in-one” compiler where every change had side effects.

The problem he wanted to solve

At the time, many compilers were built like single, large machines: the part that understood the language, the part that optimized, and the part that generated machine code were deeply intertwined. That made them effective for their original purpose, but expensive to adapt.

Lattner’s goal wasn’t “a compiler for one language.” It was a shared foundation that could power many languages and many tools—without everyone rewriting the same complex pieces over and over. The bet was that if you could standardize the middle of the pipeline, you could innovate faster at the edges.

Why “modular infrastructure” was a fresh idea

The key shift was treating compilation as a set of separable building blocks with clear boundaries. In a modular world:

- a language team can focus on parsing and developer-facing features,

- an optimization team can improve performance once and share it broadly,

- hardware support can be added without redesigning everything upstream.

This separation sounds obvious now, but it ran against the grain of how many production compilers had evolved.

Open source, built to be used by others

LLVM was released as open source early, which mattered because a shared infrastructure only works if multiple groups can trust it, inspect it, and extend it. Over time, universities, companies, and independent contributors shaped the project by adding targets, fixing corner cases, improving performance, and building new tools around it.

That community aspect wasn’t just goodwill—it was part of the design: make the core broadly useful, and it becomes worth maintaining together.

The Big Idea: Frontends, a Shared Core, and Backends

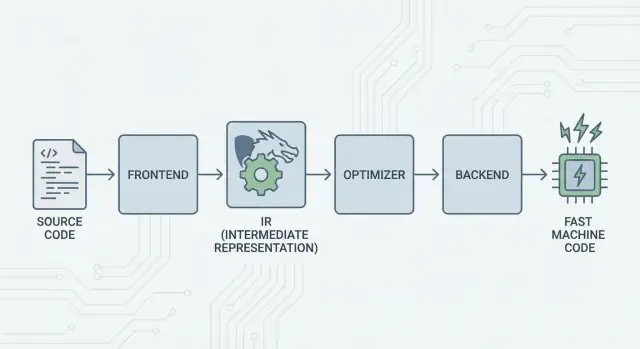

LLVM’s core idea is straightforward: split a compiler into three major pieces so many languages can share the hardest work.

1) Frontends: “What did the programmer mean?”

A frontend understands a specific programming language. It reads your source code, checks the rules (syntax and types), and turns it into a structured representation.

The key point: frontends don’t need to know every CPU detail. Their job is to translate language concepts—functions, loops, variables—into something more universal.

2) The shared middle: one common core instead of N×M work

Traditionally, building a compiler meant doing the same work over and over:

- With N languages and M chip targets, you end up with N×M combinations to support.

LLVM reduces that to:

- N frontends that translate into a shared form

- M backends that translate from that shared form to machine code

That “shared form” is LLVM’s center: a common pipeline where optimizations and analyses live. This is the big simplifier. Improvements in the middle (like better optimizations or better debugging info) can benefit many languages at once, instead of being reimplemented in every compiler.

3) Backends: “How do we make this run fast on that CPU?”

A backend takes the shared representation and produces machine-specific output: instructions for x86, ARM, and so on. This is where details like registers, calling conventions, and instruction selection matter.

An intuitive picture of the pipeline

Think of compilation as a travel route:

- Source code starts in a language-specific country (frontend).

- It crosses a border into a shared, standardized “middle language” (LLVM’s core representation and passes).

- It then takes a local train system to a specific destination city (backend for your target machine).

The result is a modular toolchain: languages can focus on expressing ideas clearly, while LLVM’s shared core focuses on making those ideas run efficiently across many platforms.

LLVM IR: The Middle Layer That Enables Reuse

LLVM IR (Intermediate Representation) is the “common language” that sits between a programming language and the machine code your CPU runs.

A compiler frontend (like Clang for C/C++) translates your source code into this shared form. Then LLVM’s optimizers and code generators work on the IR, not on the original language. Finally, a backend turns the IR into instructions for a specific target (x86, ARM, and so on).

A common language between tools and CPUs

Think of LLVM IR as a carefully designed bridge:

- Above it: many source languages can plug in (C, C++, Rust, Swift, Julia, etc.).

- Below it: many CPUs can be targeted.

- In the middle: the same analysis and optimization tools can be reused.

This is why people often describe LLVM as “compiler infrastructure” rather than “a compiler.” The IR is the shared contract that makes that infrastructure reusable.

Why IR enables reuse (and saves everyone work)

Once code is in LLVM IR, most optimization passes don’t need to know whether it started life as C++ templates, Rust iterators, or Swift generics. They mostly care about universal ideas like:

- “This value is constant.”

- “This computation is repeated; can we reuse the result?”

- “This memory load can be moved or removed safely.”

So language teams don’t have to build (and maintain) their own complete optimizer stack. They can focus on the frontend—parsing, type checking, language-specific rules—then hand off to LLVM for the heavy lifting.

What it “looks like” conceptually

LLVM IR is low-level enough to map cleanly to machine code, but still structured enough to analyze. Conceptually, it’s built from simple instructions (add, compare, load/store), explicit control flow (branches), and strongly-typed values—more like a tidy assembly language designed for compilers than something humans typically write.

How Optimizations Work (Without the Math)

When people hear “compiler optimizations,” they often imagine mysterious tricks. In LLVM, most optimizations are better understood as safe, mechanical rewrites of the program—transformations that preserve what the code does, but aim to do it faster (or smaller).

Think of it like editing, not inventing

LLVM takes your code (in LLVM IR) and repeatedly applies small improvements, much like polishing a draft:

- Remove duplicate work: If a value is computed twice and nothing changed in between, LLVM can compute it once and reuse the result.

- Simplify obvious logic: Constant expressions can be folded early (e.g., turning

3 * 4into12), so the CPU does less at runtime. - Streamline loops: Loop-related passes can reduce repeated checks, move invariant work out of the loop, or recognize patterns that can be executed more efficiently.

These changes are deliberately conservative. A pass only performs a rewrite when it can prove the rewrite won’t change the program’s meaning.

Relatable examples

If your program does this conceptually:

- Reads the same configuration value every iteration of a loop

- Performs the same calculation on the same inputs in multiple places

- Checks a condition that’s always true/false in a given context

…LLVM tries to turn that into “do the setup once,” “reuse results,” and “delete dead branches.” It’s less magic and more housekeeping.

The real tradeoff: compile time vs. runtime

Optimization isn’t free: more analysis and more passes usually mean slower compilation, even if the final program runs faster. That’s why toolchains offer levels like “optimize a little” vs. “optimize aggressively.”

Profiles can help here. With profile-guided optimization (PGO), you run the program, collect real usage data, and then recompile so LLVM focuses effort on the paths that actually matter—making the tradeoff more predictable.

Backends: Reaching Many CPUs Without Rewriting Everything

Turn Sharing into Credits

Get credits by sharing what you build or inviting others to try Koder.ai.

A compiler has two very different jobs. First, it needs to understand your source code. Second, it needs to produce machine code that a specific CPU can execute. LLVM backends focus on that second job.

What a backend actually does

Think of LLVM IR as a “universal recipe” for what the program should do. A backend turns that recipe into the exact instructions for a particular processor family—x86-64 for most desktops and servers, ARM64 for many phones and newer laptops, or specialized targets like WebAssembly.

Concretely, a backend is responsible for:

- Instruction selection: mapping IR operations to real CPU instructions

- Register allocation: choosing which values live in fast CPU registers vs. memory

- Scheduling: ordering instructions so the CPU can run them efficiently

- Assembly/object output: emitting code the linker and OS understand

Why shared infrastructure makes new hardware support easier

Without a shared core, every language would need to re-implement all of this for every CPU it wants to support—an enormous amount of work, and a constant maintenance burden.

LLVM flips that: frontends (like Clang) produce LLVM IR once, and backends handle the “last mile” per target. Adding support for a new CPU generally means writing one backend (or extending an existing one), not rewriting every compiler in existence.

Portability for teams shipping on multiple platforms

For projects that must run on Windows/macOS/Linux, on x86 and ARM, or even in the browser, LLVM’s backend model is a practical advantage. You can keep one codebase and largely one build pipeline, then retarget by choosing a different backend (or cross-compiling).

That portability is why LLVM shows up everywhere: it’s not only about speed—it’s also about avoiding repeated, platform-specific compiler work that slows teams down.

Clang: Where Many Developers First Feel LLVM

Clang is the C, C++, and Objective-C frontend that plugs into LLVM. If LLVM is the shared engine that can optimize and generate machine code, Clang is the part that reads your source files, understands the language rules, and turns what you wrote into a form LLVM can work with.

Why Clang got noticed

Many developers didn’t discover LLVM by reading compiler papers—they encountered it the first time they swapped compilers and the feedback suddenly improved.

Clang’s diagnostics are known for being more readable and more specific. Instead of vague errors, it often points to the exact token that triggered the problem, shows the relevant line, and explains what it expected. That matters in day-to-day work because the “compile, fix, repeat” loop becomes less frustrating.

Clang also exposes clean, well-documented interfaces (notably through libclang and the broader Clang tooling ecosystem). That made it easier for editors, IDEs, and other developer tools to integrate deep language understanding without reinventing a C/C++ parser.

How it shows up in daily workflows

Once a tool can reliably parse and analyze your code, you start getting features that feel less like text editing and more like working with a structured program:

- Accurate code navigation (“jump to definition,” “find references”) even in large, macro-heavy C++ projects

- Refactoring support that understands symbols and scopes, not just search-and-replace

- Inline hints and quick fixes driven by real syntax and type information

This is why Clang is often the first “touch point” for LLVM: it’s where practical developer experience improvements originate. Even if you never think about LLVM IR or backends, you still benefit when your editor’s autocomplete is smarter, your static checks are more precise, and your build errors are easier to act on.

Why Many Modern Languages Build on LLVM

LLVM is appealing to language teams for a simple reason: it lets them focus on the language instead of spending years reinventing a full optimizing compiler.

Faster time-to-market

Building a new language already involves parsing, type-checking, diagnostics, package tooling, documentation, and community support. If you also have to create a production-grade optimizer, code generator, and platform support from scratch, shipping gets delayed—sometimes by years.

LLVM provides a ready-made compilation core: register allocation, instruction selection, mature optimization passes, and targets for common CPUs. Teams can plug in a frontend that lowers their language into LLVM IR, then rely on the existing pipeline to produce native code for macOS, Linux, and Windows.

High performance (without “heroics”)

LLVM’s optimizer and backends are the result of long-term engineering and constant real-world testing. That translates into strong baseline performance for languages that adopt it—often good enough early on, and capable of improving as LLVM improves.

That’s part of why several well-known languages have built around it:

- Swift uses LLVM to generate highly optimized native binaries across Apple platforms.

- Rust relies on LLVM for code generation and many architecture targets.

- Julia uses LLVM to enable fast numerical code, including runtime compilation for specialized workloads.

Not every language needs LLVM

Choosing LLVM is a tradeoff, not a requirement. Some languages prioritize tiny binaries, ultra-fast compilation, or tight control over the entire toolchain. Others already have established compilers (like GCC-based ecosystems) or prefer simpler backends.

LLVM is popular because it’s a strong default—not because it’s the only valid path.

JIT and Runtime Compilation: Fast Feedback Loops

Recover Fast

Undo a bad change quickly and keep moving without losing momentum.

“Just-in-time” (JIT) compilation is easiest to think of as compiling as you run. Instead of translating all code ahead of time into a final executable, a JIT engine waits until a piece of code is actually needed, then compiles that part on the fly—often using real runtime information (like the exact types and sizes of data) to make better choices.

Why JIT can feel so fast

Because you don’t have to compile everything up front, JIT systems can deliver quick feedback for interactive work. You write or generate a bit of code, run it immediately, and the system compiles only what’s necessary right now. If that same code runs repeatedly, the JIT can cache the compiled result or recompile “hot” sections more aggressively.

Where runtime compilation helps in practice

JIT shines when workloads are dynamic or interactive:

- REPLs and notebooks: Evaluate snippets instantly while still getting native-speed execution for heavy loops.

- Plugins and extensions: Applications can load user code at runtime and compile it to match the host CPU.

- Dynamic workloads: When inputs vary a lot, runtime profiling can guide which paths deserve optimization.

- Scientific computing: Generated kernels (for a specific matrix size, model shape, or hardware feature) can be compiled on demand.

LLVM’s role (without the hype)

LLVM doesn’t magically make every program faster, and it isn’t a complete JIT by itself. What it provides is a toolkit: a well-defined IR, a large set of optimization passes, and code generation for many CPUs. Projects can build JIT engines on top of those building blocks, choosing the right tradeoff between startup time, peak performance, and complexity.

Performance, Predictability, and Real-World Tradeoffs

LLVM-based toolchains can produce extremely fast code—but “fast” is not a single, stable property. It depends on the exact compiler version, target CPU, optimization settings, and even what you ask the compiler to assume about the program.

Why “same source, different results” happens

Two compilers can read the same C/C++ (or Rust, Swift, etc.) source and still generate noticeably different machine code. Some of that is intentional: each compiler has its own set of optimization passes, heuristics, and default settings. Even within LLVM, Clang 15 and Clang 18 may make different inlining decisions, vectorize different loops, or schedule instructions differently.

It can also be caused by undefined behavior and unspecified behavior in the language. If your program accidentally relies on something the standard doesn’t guarantee (like signed overflow in C), different compilers—or different flags—may “optimize” in ways that change results.

Determinism, debug builds, and release builds

People often expect compilation to be deterministic: same inputs, same outputs. In practice, you’ll get close, but not always identical binaries across environments. Build paths, timestamps, link order, profile-guided data, and LTO choices can all affect the final artifact.

The bigger, more practical distinction is debug vs. release. Debug builds typically disable many optimizations to preserve step-by-step debugging and readable stack traces. Release builds enable aggressive transformations that can reorder code, inline functions, and remove variables—great for performance, but sometimes harder to debug.

Practical advice: measure, don’t guess

Treat performance as a measurement problem:

- Benchmark on representative hardware and realistic datasets.

- Warm up caches and run multiple iterations.

- Compare builds with explicit flags (for example, changing

-O2vs-O3, enabling/disabling LTO, or selecting a target with-march).

Small flag changes can shift performance in either direction. The safest workflow is: pick a hypothesis, measure it, and keep benchmarks close to what your users actually run.

Tooling Beyond Compilation: Analysis, Debugging, and Safety

Ship a Full Stack App

Generate a React front end with a Go and PostgreSQL backend in one flow.

LLVM is often described as a compiler toolkit, but many developers feel its impact through tools that sit around compilation: analyzers, debuggers, and safety checks that can be turned on during builds and tests.

Analysis and instrumentation as “add-ons”

Because LLVM exposes a well-defined intermediate representation (IR) and a pass pipeline, it’s natural to build extra steps that inspect or rewrite code for a purpose other than speed. A pass might insert counters for profiling, mark suspicious memory operations, or gather coverage data.

The key point is that these features can be integrated without each language team reinventing the same plumbing.

Sanitizers: catching bugs close to the source

Clang and LLVM popularized a family of runtime “sanitizers” that instrument programs to detect common classes of bugs during testing—think out-of-bounds memory access, use-after-free, data races, and undefined behavior patterns. They’re not magic shields, and they typically slow programs down, so they’re mainly used in CI and pre-release testing. But when they trigger, they often point to a precise source location and a readable explanation, which is exactly what teams need when chasing intermittent crashes.

Better diagnostics = faster onboarding

Tooling quality is also about communication. Clear warnings, actionable error messages, and consistent debug info reduce the “mystery factor” for newcomers. When the toolchain explains what happened and how to fix it, developers spend less time memorizing compiler quirks and more time learning the codebase.

LLVM doesn’t guarantee perfect diagnostics or safety on its own, but it provides a common foundation that makes these developer-facing tools practical to build, maintain, and share across many projects.

When to Use LLVM (and When Not To)

LLVM is best thought of as a “build-your-own compiler and tooling kit.” That flexibility is exactly why it powers so many modern toolchains—but it’s also why it isn’t the right answer for every project.

When LLVM is a great fit

LLVM shines when you want to reuse serious compiler engineering without reinventing it.

If you’re building a new programming language, LLVM can give you a proven optimization pipeline, mature code generation for many CPUs, and a path to good debugging support.

If you’re shipping cross-platform applications, LLVM’s backend ecosystem reduces the work needed to target different architectures. You focus on your language or product logic, rather than writing separate code generators.

If your goal is developer tooling—linters, static analysis, code navigation, refactoring—LLVM (and the broader ecosystem around it) is a strong foundation because the compiler already “understands” code structure and types.

When it may be overkill

LLVM can be heavy if you’re working on tiny embedded systems where build size, memory, and compile time are tightly constrained.

It may also be a poor fit for very specialized pipelines where you don’t want general-purpose optimizations, or where your “language” is closer to a fixed DSL with a straightforward direct-to-machine-code mapping.

A simple checklist

Ask these three questions:

- Do we need to target multiple platforms/CPUs now or soon?

- Do we benefit from existing optimizations and debug info, rather than building our own?

- Do we want an ecosystem path (tooling, integrations, hiring) more than a minimal custom compiler?

If you answered “yes” to most, LLVM is usually a practical bet. If you mainly want the smallest, simplest compiler that solves one narrow problem, a lighter approach can win.

A practical note for product teams: LLVM’s benefits, without becoming compiler experts

Most teams don’t want to “adopt LLVM” as a project. They want outcomes: cross-platform builds, fast binaries, good diagnostics, and reliable tooling.

That’s one reason platforms like Koder.ai are interesting in this context. If your workflow is increasingly driven by higher-level automation (planning, generating scaffolding, iterating in a tight loop), you still benefit from LLVM indirectly through the toolchains underneath—whether you’re building a React web app, a Go backend with PostgreSQL, or a Flutter mobile client. Koder.ai’s chat-driven “vibe-coding” approach focuses on shipping product faster, while modern compiler infrastructure (LLVM/Clang and friends, where applicable) continues to do the unglamorous work of optimization, diagnostics, and portability in the background.