Jan 01, 2026·6 min

Claude Code for Go API scaffolding: consistent handlers and services

Claude Code for Go API scaffolding: define one clean handler-service-error pattern, then generate new endpoints that stay consistent across your Go API.

Claude Code for Go API scaffolding: define one clean handler-service-error pattern, then generate new endpoints that stay consistent across your Go API.

Go APIs usually start clean: a few endpoints, one or two people, and everything lives in everyone's head. Then the API grows, features ship under pressure, and small differences sneak in. Each one feels harmless, but together they slow every future change.

A common example: one handler decodes JSON into a struct and returns 400 with a helpful message, another returns 422 with a different shape, and a third logs errors in a different format. None of that breaks compilation. It just creates constant decision-making and tiny rewrites every time you add something.

You feel the mess in places like:

CreateUser, AddUser, RegisterUser) that makes searching harder."Scaffolding" here means a repeatable template for new work: where code goes, what each layer does, and what responses look like. It's less about generating lots of code and more about locking in a consistent shape.

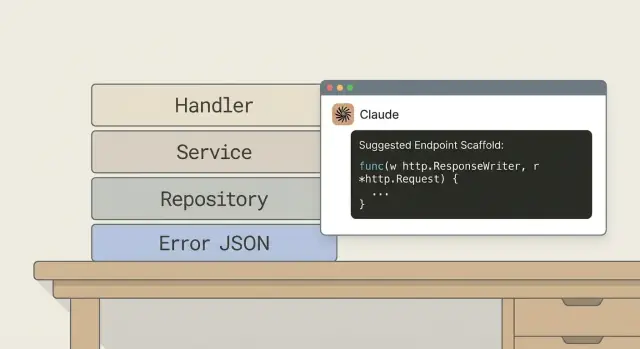

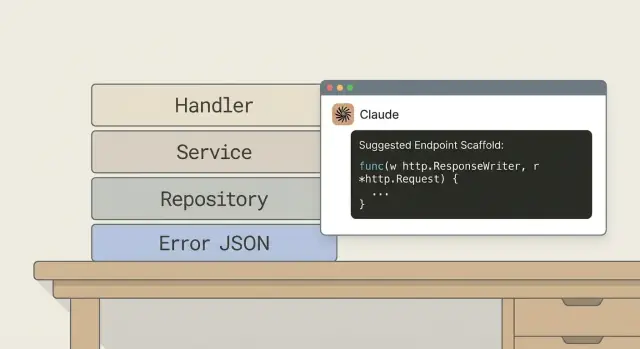

Tools like Claude can help you scaffold new endpoints fast, but they only stay helpful when you treat the pattern as a rule. You define the rules, you review every diff, and you run tests. The model fills in the standard parts; it doesn't get to redefine your architecture.

A Go API stays easy to grow when every request follows the same path. Before you start generating endpoints, pick one layer split and stick to it.

The handler's job is HTTP only: read the request, call the service, and write the response. It shouldn't contain business rules, SQL, or "just this one special case" logic.

The service owns the use case: business rules, decisions, and orchestration across repositories or external calls. It shouldn't know about HTTP concerns like status codes, headers, or how errors are rendered.

Data access (repository/store) owns persistence details. It translates service intent into SQL/queries/transactions. It shouldn't enforce business rules beyond basic data integrity, and it shouldn't shape API responses.

A separation checklist that stays practical:

Pick one rule and don't bend it.

A simple approach:

Example: the handler checks that email is present and looks like an email. The service checks that the email is allowed and not already in use.

Decide early whether services return domain types or DTOs.

A clean default is: handlers use request/response DTOs, services use domain types, and the handler maps domain to response. That keeps the service stable even when the HTTP contract changes.

If mapping feels heavy, keep it consistent anyway: have the service return a domain type plus a typed error, and keep the JSON shaping in the handler.

If you want generated endpoints to feel like they were written by the same person, lock down error responses early. Generation works best when the output format is non-negotiable: one JSON shape, one status-code map, and one rule for what gets exposed.

Start with a single error envelope that every endpoint returns on failure. Keep it small and predictable:

{

"code": "validation_failed",

"message": "One or more fields are invalid.",

"details": {

"fields": {

"email": "must be a valid email address",

"age": "must be greater than 0"

}

},

"request_id": "req_01HR..."

}

Use code for machines (stable and predictable) and message for humans (short and safe). Put optional structured data into details. For validation, a simple details.fields map is easy to generate and easy for clients to display next to inputs.

Next, write down a status code map and stick to it. The less debate per endpoint, the better. If you want both 400 and 422, make the split explicit:

bad_json -> 400 Bad Request (malformed JSON)validation_failed -> 422 Unprocessable Content (well-formed JSON, invalid fields)not_found -> 404 Not Foundconflict -> 409 Conflict (duplicate key, version mismatch)unauthorized -> 401 Unauthorizedforbidden -> 403 Forbiddeninternal -> 500 Internal Server ErrorDecide what you log vs what you return. A good rule: clients get a safe message and a request ID; logs get the full error and internal context (SQL, upstream payloads, user IDs) that you would never want to leak.

Finally, standardize request_id. Accept an incoming ID header if present (from an API gateway), otherwise generate one at the edge (middleware). Attach it to the context, include it in logs, and return it in every error response.

If you want scaffolding to stay consistent, your folder layout has to be boring and repeatable. Generators follow patterns they can see, but they drift when files are scattered or names change per feature.

Pick one naming convention and don't bend it. Choose one word for each thing and keep it: handler, service, repo, request, response. If the route is POST /users, name files and types around users and create (not sometimes register, sometimes addUser).

A simple layout that matches the usual layers:

internal/

httpapi/

handlers/

users_handler.go

services/

users_service.go

data/

users_repo.go

apitypes/

users_types.go

Decide where shared types live, because this is where projects often get messy. One useful rule:

internal/apitypes (match JSON and validation needs).If a type has JSON tags and is designed for clients, treat it as an API type.

Keep handler dependencies minimal and make that rule explicit:

Write a short pattern doc in the repo root (plain Markdown is fine). Include the folder tree, naming rules, and one tiny example flow (handler -> service -> repo, plus which file each piece belongs in). This is the exact reference you paste into your generator so new endpoints match the structure every time.

Before generating ten endpoints, create one endpoint you trust. This is the gold standard: the file you can point to and say, "New code must look like this." You can write it from scratch or refactor an existing one until it matches.

Keep the handler thin. One move that helps a lot: put an interface between the handler and the service so the handler depends on a contract, not a concrete struct.

Add small comments in the reference endpoint only where future generated code might stumble. Explain decisions (why 400 vs 422, why create returns 201, why you hide internal errors behind a generic message). Skip comments that just restate code.

Once the reference endpoint works, extract helpers so every new endpoint has fewer chances to drift. The most reusable helpers are usually:

Here's what "thin handler + interface" can look like in practice:

type UserService interface {

CreateUser(ctx context.Context, in CreateUserInput) (User, error)

}

func (h *Handler) CreateUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var in CreateUserRequest

if err := BindJSON(r, &in); err != nil {

WriteError(w, ErrBadJSON) // 400: malformed JSON

return

}

if err := Validate(in); err != nil {

WriteError(w, err) // 422: validation details

return

}

user, err := h.svc.CreateUser(r.Context(), in.ToInput())

if err != nil {

WriteError(w, err)

return

}

WriteJSON(w, http.StatusCreated, user)

}

Lock it in with a couple of tests (even a small table test for error mapping). Generation works best when it has one clean target to imitate.

Consistency starts with what you paste in and what you forbid. For a new endpoint, give two things:

Include the handler, service method, request/response types, and any shared helpers the endpoint uses. Then state the contract in plain terms:

POST /v1/widgets)Be explicit about what must match: naming, package paths, and helper functions (WriteJSON, BindJSON, WriteError, your validator).

A tight prompt prevents "helpful" refactors. For example:

Using the reference endpoint below and the pattern notes, generate a new endpoint.

Contract:

- Route: POST /v1/widgets

- Request: {"name": string, "color": string}

- Response: {"id": string, "name": string, "color": string, "createdAt": string}

- Errors: invalid JSON -> 400; validation -> 422; duplicate name -> 409; unexpected -> 500

Output ONLY these files:

1) internal/http/handlers/widgets_create.go

2) internal/service/widgets.go (add method only)

3) internal/types/widgets.go (add types only)

Do not change: router setup, existing error format, existing helpers, or unrelated files.

Must use: package paths and helper functions exactly as in the reference.

If you use tests, request them explicitly (and name the test file). Otherwise the model may skip them or invent a test setup.

Do a quick diff check after generation. If it modified shared helpers, router registration, or your standard error response, reject the output and restate the "do not change" rules more strictly.

The output is only as consistent as the input you give. The fastest way to avoid "almost right" code is to reuse one prompt template every time, with a small context snapshot pulled from your repo.

Copy, paste, and fill the placeholders:

You are editing an existing Go HTTP API.

CONTEXT

- Folder tree (only the relevant parts):

<paste a small tree: internal/http, internal/service, internal/repo, etc>

- Key types and patterns:

- Handler signature style: <example>

- Service interface style: <example>

- Request/response DTOs live in: <package>

- Standard error response JSON:

{

"error": {

"code": "invalid_argument",

"message": "...",

"details": {"field": "reason"}

}

}

- Status code map:

invalid_json -> 400

invalid_argument -> 422

not_found -> 404

conflict -> 409

internal -> 500

TASK

Add a new endpoint: <METHOD> <PATH>

- Handler name: <Name>

- Service method: <Name>

- Request JSON example:

{"name":"Acme"}

- Success response JSON example:

{"id":"123","name":"Acme"}

CONSTRAINTS

- No new dependencies.

- Keep functions small and single-purpose.

- Match existing naming, folder layout, and error style exactly.

- Do not refactor unrelated files.

ACCEPTANCE CHECKS

- Code builds.

- Existing tests pass (add tests only if the repo already uses them for handlers/services).

- Run gofmt on changed files.

FINAL INSTRUCTION

Before writing code, list any assumptions you must make. If an assumption is risky, ask a short question instead.

This works because it forces three things: a context block (what exists), a constraints block (what not to do), and concrete JSON examples (so shapes don't drift). The final instruction is your safety catch: if the model is unsure, it should say so before it commits you to a new pattern.

Say you want to add a "Create project" endpoint. The goal is simple: accept a name, enforce a few rules, store it, and return a new ID. The tricky part is keeping the same handler-service-repo split and the same error JSON you already use.

A consistent flow looks like this:

Here's the request the handler accepts:

{ "name": "Roadmap", "owner_id": "u_123" }

On success, return 201 Created. The ID should come from one place every time. For example, let Postgres generate it and have the repo return it:

{ "id": "p_456", "name": "Roadmap", "owner_id": "u_123", "created_at": "2026-01-09T12:34:56Z" }

Two realistic failure paths:

If validation fails (missing or too short name), return a field-level error using your standard shape and your chosen status code:

{ "error": { "code": "VALIDATION_ERROR", "message": "Invalid request", "details": { "name": "must be at least 3 characters" } } }

If the name must be unique per owner and the service finds an existing project, return 409 Conflict:

{ "error": { "code": "PROJECT_NAME_TAKEN", "message": "Project name already exists", "details": { "name": "Roadmap" } } }

One decision that keeps the pattern clean: the handler checks "is this request shaped correctly?" while the service owns "is this allowed?" That separation makes generated endpoints predictable.

The fastest way to lose consistency is to let the generator improvise.

One common drift is a new error shape. One endpoint returns {error: "..."}, another returns {message: "..."}, and a third adds a nested object. Fix this by keeping a single error envelope and a single status code map in one place, then requiring new endpoints to reuse them by import path and function name. If the generator proposes a new field, treat it like an API change request, not a convenience.

Another drift is handler bloat. It starts small: validate, then check permissions, then query the DB, then branch on business rules. Soon every handler looks different. Keep one rule: handlers translate HTTP into typed inputs and outputs; services own decisions; data access owns queries.

Naming mismatches also add up. If one endpoint uses CreateUserRequest and another uses NewUserPayload, you'll waste time hunting types and writing glue. Pick a naming scheme and reject new names unless there's a strong reason.

Never return raw database errors to clients. Aside from leaking details, it creates inconsistent messages and status codes. Wrap internal errors, log the cause, and return a stable public error code.

Avoid adding new libraries "just for convenience". Each extra validator, router helper, or error package becomes another style to match.

Guardrails that prevent most breakage:

If you can't diff two endpoints and see the same shape (imports, flow, error handling), tighten the prompt and regenerate before merging.

Before you merge anything generated, check structure first. If the shape is right, logic bugs are easier to spot.

Structure checks:

request_id behavior.Behavior checks:

Treat your pattern as a shared contract, not a preference. Keep the "how we build endpoints" doc next to your code, and maintain one reference endpoint that shows the full approach end to end.

Scale up generation in small batches. Generate 2 to 3 endpoints that hit different edges (a simple read, a create with validation, an update with a not-found case). Then stop and refine. If reviews keep finding the same style drift, update the baseline doc and the reference endpoint before generating more.

A loop you can repeat:

If you want a tighter build-review loop, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai (koder.ai) can help you scaffold and iterate quickly in a chat-driven workflow, then export the source code once it matches your standard. The tool matters less than the rule: your baseline stays in charge.

Lock down a repeatable template early: a consistent layer split (handler → service → data access), one error envelope, and a status-code map. Then use a single “reference endpoint” as the example every new endpoint must copy.

Keep handlers HTTP-only:

If you see SQL, permission checks, or business branching in a handler, push that into the service.

Put business rules and decisions in the service:

The service should return domain results and typed errors—no HTTP status codes, no JSON shaping.

Keep persistence concerns isolated:

Avoid encoding API response formats or enforcing business rules in the repo beyond basic data integrity.

A simple default:

Example: handler checks email is present and looks like an email; service checks it’s allowed and not already in use.

Use one standard error envelope everywhere and keep it stable. A practical shape is:

code for machines (stable)message for humans (short and safe)details for structured extras (like field errors)request_id for tracingThis avoids client-side special cases and keeps generated endpoints predictable.

Write down a status-code map and follow it every time. A common split:

Return safe, consistent public errors, and log the real cause internally.

code, short message, plus request_idThis prevents leaking internals and avoids random error message differences across endpoints.

Create one “golden” endpoint you trust and require new endpoints to match it:

BindJSON, WriteJSON, WriteError, etc.)Then add a couple of small tests (even table tests for error mapping) to lock the pattern in.

Give the model strict context and constraints:

After generation, reject diffs that “improve” architecture instead of following the baseline.

400 for malformed JSON (bad_json)422 for validation failures (validation_failed)404 for missing resources (not_found)409 for conflicts (duplicates/version mismatches)500 for unexpected failuresThe key is consistency: no debating per endpoint.