Dec 14, 2025·6 min

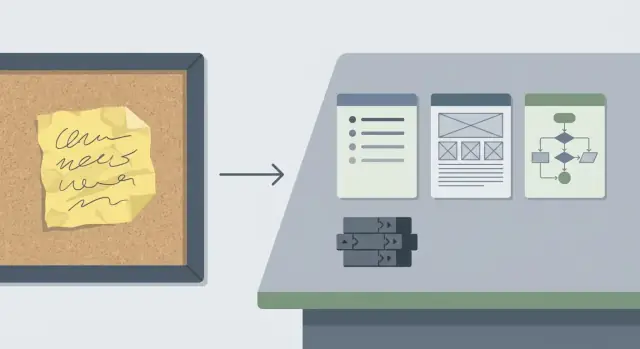

Claude Code task scoping: from vague requests to commits

Learn Claude Code task scoping to turn messy feature requests into clear acceptance criteria, a minimal UI/API plan, and a few small commits.

Why vague feature requests waste time

A vague request sounds harmless: “Add a better search,” “Make onboarding smoother,” “Users need notifications.” In real teams it often arrives as a one-line chat message, a screenshot with arrows, or a half-remembered customer call. Everyone agrees, but everyone pictures something different.

The cost shows up later. When scope is unclear, people build on guesses. The first demo turns into another round of clarification: “That’s not what I meant.” Work gets redone, and the change quietly grows. Design tweaks trigger code changes, which trigger more testing. Reviews slow down because a fuzzy change is hard to verify. If nobody can define what “correct” looks like, reviewers end up debating behavior instead of checking quality.

You can usually spot a vague task early:

- No step-by-step example of what a user should be able to do

- No edge cases (empty states, permissions, errors)

- “Just in case” work that balloons into a huge PR

- Review comments arguing about behavior, not implementation

- “We’ll figure it out as we go” becomes the plan

A well-scoped task gives the team a finish line: clear acceptance criteria, a minimal UI and API plan, and explicit boundaries around what’s not included. That’s the difference between “improve search” and a small change that’s easy to build and review.

One practical habit: separate “definition of done” from “nice-to-have.” “Done” is a short list of checks you can run (for example: “Search returns results by title, shows ‘No results’ when empty, and keeps the query in the URL”). “Nice-to-have” is everything that can wait (synonyms, ranking tweaks, highlighting, analytics). Labeling those up front prevents accidental scope growth.

Start with the outcome, not the solution

Vague requests often start as proposed fixes: “Add a button,” “Switch to a new flow,” “Use a different model.” Pause and translate the suggestion into an outcome first.

A simple format helps: “As a [user], I want to [do something], so I can [reach a goal].” Keep it plain. If you can’t say it in one breath, it’s still too fuzzy.

Next, describe what changes for the user when it’s done. Focus on visible behavior, not implementation details. For example: “After I submit the form, I see a confirmation and can find the new record in the list.” That creates a clear finish line and makes it harder for “just one more tweak” to sneak in.

Also write down what stays the same. Non-goals protect your scope. If the request is “improve onboarding,” a non-goal might be “no dashboard redesign” or “no pricing-tier logic changes.”

Finally, pick one primary path to support first: the single end-to-end slice that proves the feature works.

Example: instead of “add snapshots everywhere,” write: “As a project owner, I can restore the latest snapshot of my app, so I can undo a bad change.” Non-goals: “no bulk restore, no UI redesign.”

Ask the few questions that remove ambiguity

A vague request is rarely missing effort. It’s missing decisions.

Start with constraints that quietly change scope. Deadlines matter, but so do access rules and compliance needs. If you’re building on a platform with tiers and roles, decide early who gets the feature and under what plan.

Then ask for one concrete example. A screenshot, a competitor behavior, or a prior ticket reveals what “better” actually means. If the requester has none, ask them to replay the last time they felt the pain: what screen were they on, what did they click, what did they expect?

Edge cases are where scope explodes, so name the big ones early: empty data, validation errors, slow or failed network calls, and what “undo” really means.

Finally, decide how you’ll verify success. Without a testable outcome, the task turns into opinions.

These five questions usually remove most of the ambiguity:

- Who gets access (tier and roles)?

- What’s the deadline, and what’s the smallest acceptable version?

- What’s one example of the expected behavior?

- What should happen on empty states, errors, and slow connections?

- How will we confirm it works (specific criteria or metric)?

Example: “Add custom domains for clients” gets clearer once you decide which tier it belongs to, who can set it up, whether hosting location matters for compliance, what error shows for invalid DNS, and what “done” means (domain verified, HTTPS active, and a safe rollback plan).

Convert messy notes into acceptance criteria

Messy requests mix goals, guesses, and half-remembered edge cases. The job is to turn that into statements anyone can test without reading your mind. The same criteria should guide design, coding, review, and QA.

A simple pattern keeps it clear. You can use Given/When/Then, or short bullets that mean the same thing.

A quick acceptance-criteria template

Write each criterion as a single test someone could run:

- Given a starting state, when the user does X, then Y happens.

- Include validation rules (what inputs are allowed).

- Include at least one failure case (what error the user sees).

- Define the “done signal” (what QA checks, what reviewers expect).

Now apply it. Suppose the note says: “Make snapshots easier. I want to roll back if the last change breaks things.” Turn it into testable statements:

- Given a project with 2 snapshots, when I open Snapshots, then I see both with time and a short label.

- Given a snapshot, when I click Roll back and confirm, then the project returns to that snapshot and the app builds successfully.

- Given I am not the project owner, when I try to roll back, then I see an error and nothing changes.

- Given a rollback is in progress, when I refresh the page, then I can still see status and final result.

- Given a rollback fails, when it stops, then I see a clear message and the current version stays active.

If QA can run these checks and reviewers can verify them in the UI and logs, you’re ready to plan the UI and API work and split it into small commits.

Draft a minimal UI plan

A minimal UI plan is a promise: the smallest visible change that proves the feature works.

Start by naming which screens will change and what a person will notice in 10 seconds. If the request says “make it easier” or “clean it up,” translate that into one concrete change you can point to.

Write it as a small map, not a redesign. For example: “Orders page: add a filter bar above the table,” or “Settings: add a new toggle under Notifications.” If you can’t name the screen and the exact element that changes, the scope is still unclear.

Define the key UI states

Most UI changes need a few predictable states. Spell out only the ones that apply:

- Loading

- Empty

- Error (and whether retry exists)

- Success (toast, inline message, updated list)

Confirm the words users will see

UI copy is part of scope. Capture labels and messages that must be approved: button text, field labels, helper text, and error messages. If wording is still open, mark it as placeholder copy and note who will confirm it.

Keep a small “not now” note for anything that isn’t required to use the feature (responsive polish, advanced sorting, animations, new icons).

Draft a minimal API and data plan

Make reviews faster

Turn acceptance criteria into a clear checklist your team can review and test.

A scoped task needs a small, clear contract between UI, backend, and data. The goal isn’t to design the entire system. It’s to define the smallest set of requests and fields that prove the feature works.

Start by listing the data you need and where it comes from: existing fields you can read, new fields you must store, and values you can compute. If you can’t name a source for each field, you don’t have a plan yet.

Keep the API surface small. For many features, one read and one write is enough:

GET /items/{id}returns the state needed to render the screenPOST /items/{id}/updateaccepts only what the user can change and returns the updated state

Write inputs and outputs as plain objects, not paragraphs. Include required vs optional fields, and what happens on common errors (not found, validation failed).

Do a quick auth pass before touching the database. Decide who can read and who can write, and state the rule in one sentence (for example: “any signed-in user can read, only admins can write”). Skipping this often leads to rework.

Finally, decide what must be stored and what can be computed. A simple rule: store facts, compute views.

Use Claude Code to produce a scoped task

Claude Code works best when you give it a clear target and a tight box. Start by pasting the messy request and any constraints (deadline, users affected, data rules). Then ask for a scoped output that includes:

- A plain-language restatement of the scope and a short acceptance-criteria checklist.

- A small sequence of commits (aim for 3 to 7), each with a clear outcome.

- Likely files or folders touched per commit, and what changes inside them.

- A quick test plan per commit (one happy path and one edge case).

- Explicit out-of-scope notes.

After it replies, read it like a reviewer. If you see phrases like “improve performance” or “make it cleaner,” ask for measurable wording.

Mini example (what “good” looks like)

Request: “Add a way to pause a subscription.”

A scoped version might say: “User can pause for 1 to 3 months; next billing date updates; admin can see pause status,” and out of scope: “No proration changes.”

From there, the commit plan becomes practical: one commit for DB and API shape, one for UI controls, one for validation and error states, one for end-to-end tests.

Split work into small, reviewable commits

From ticket to prototype

Turn your UI and API notes into a working app without starting from scratch.

Big changes hide bugs. Small commits make reviews faster, make rollbacks safer, and help you notice when you drift away from the acceptance criteria.

A useful rule: each commit should unlock one new behavior, and include a quick way to prove it works.

A common sequence looks like this:

- Data model or migration (if needed) plus tests

- API behavior and validation

- UI wiring with empty and error states

- Logging or analytics only if required, then small polish

Keep each commit focused. Avoid “while I was here” refactors. Keep the app working end to end, even if the UI is basic. Don’t bundle migrations, behavior, and UI into one commit unless you have a strong reason.

Walkthrough: “Export reports”

A stakeholder says: “Can we add Export reports?” It hides a lot of choices: which report, which format, who can export, and how delivery works.

Ask only the questions that change the design:

- Which report types are in scope for v1?

- What format is required for v1 (CSV, PDF)?

- Who can export (admins, specific roles)?

- Is it a direct download or an emailed export?

- Any limits (date range max, row count cap, timeouts)?

Assume the answers are: “Sales Summary report, CSV only, manager role, direct download, last 90 days max.” Now the v1 acceptance criteria becomes concrete: managers can click Export on the Sales Summary page; the CSV matches the on-screen table columns; the export respects current filters; exporting more than 90 days shows a clear error; the download completes within 30 seconds for up to 50k rows.

Minimal UI plan: one Export button near table actions, a loading state while generating, and an error message that tells the user how to fix the issue (like “Choose 90 days or less”).

Minimal API plan: one endpoint that takes filters and returns a generated CSV as a file response, reusing the same query as the table while enforcing the 90-day rule server-side.

Then ship it in a few tight commits: first the endpoint for a fixed happy path, then UI wiring, then validation and user-facing errors, then tests and documentation.

Common scoping mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Hidden requirements sneak in

Requests like “add team roles” often hide rules about inviting, editing, and what happens to existing users. If you catch yourself guessing, write the assumption down and turn it into a question or an explicit rule.

UI polish gets mixed with core behavior

Teams lose days when one task includes both “make it work” and “make it pretty.” Keep the first task focused on behavior and data. Put styling, animations, and spacing into a follow-up task unless they’re required to use the feature.

You try to solve every edge case in v1

Edge cases matter, but not all of them need to be solved immediately. Handle the few that can break trust (double submits, conflicting edits) and defer the rest with clear notes.

Error states and permissions get pushed to “later”

If you don’t write them down, you’ll miss them. Include at least one unhappy path and at least one permission rule in your acceptance criteria.

Criteria you can’t verify

Avoid “fast” or “intuitive” unless you attach a number or a concrete check. Replace them with something you can prove in review.

Quick checklist before you start coding

Decide access up front

Bake roles and access into the plan so permissions do not become rework.

Pin the task down so a teammate can review and test without mind-reading:

- Outcome and non-goals: one sentence for the outcome, plus 1 to 3 explicit non-goals.

- Acceptance criteria: 5 to 10 testable checks in plain language.

- UI states: the minimum loading, empty, error, and success states.

- API and data notes: the smallest endpoint shape and any data changes, plus who can read and write.

- Commit plan with tests: 3 to 7 commits, each with a quick proof.

Example: “Add saved searches” becomes “Users can save a filter and reapply it later,” with non-goals like “no sharing” and “no sorting changes.”

Next steps: keep scope stable while you build

Once you have a scoped task, protect it. Before coding, do a quick sanity review with the people who asked for the change:

- Read the acceptance criteria and confirm it matches the outcome.

- Confirm permissions, empty states, and failure behavior.

- Reconfirm what’s out of scope.

- Agree on the smallest UI and API changes that meet the criteria.

- Decide how you’ll demo it and what “done” looks like.

Then store the criteria where the work happens: in the ticket, in the PR description, and anywhere your team actually looks.

If you’re building in Koder.ai (koder.ai), it helps to lock the plan first and then generate code from it. Planning Mode is a good fit for that workflow, and snapshots and rollback can keep experiments safe when you need to try an approach and back it out.

When new ideas pop up mid-build, keep scope stable: write them into a follow-up list, pause to re-scope if they change the acceptance criteria, and keep commits tied to one criterion at a time.

FAQ

How do I know a feature request is too vague to start building?

Start by writing the outcome in one sentence (what the user can do when it’s done), then add 3–7 acceptance criteria that a tester can verify.

If you can’t describe the “correct” behavior without debating it, the task is still vague.

What’s the fastest way to turn “do X better” into a clear outcome?

Use this quick format:

- As a [user]

- I want to [action]

- So I can [goal]

Then add one concrete example of the expected behavior. If you can’t give an example, replay the last time the problem happened and write what the user clicked and expected to see.

How should I separate “done” from “nice-to-have” without arguing for days?

Write a short “Definition of done” list first (the checks that must pass), then a separate “Nice-to-have” list.

Default rule: if it’s not needed to prove the feature works end-to-end, it goes into nice-to-have.

What questions remove the most ambiguity early?

Ask the few questions that change scope:

- Who gets access (tier and roles)?

- What’s the deadline, and what’s the smallest acceptable version?

- What’s one example of expected behavior?

- What happens on empty states, errors, and slow connections?

- How will we confirm it works (criteria or a metric)?

These force the missing decisions into the open.

Which edge cases should I include in v1 acceptance criteria?

Treat edge cases as scope items, not surprises. For v1, cover the ones that break trust:

- Empty state

- Validation errors

- Permission denied

- Network/API failures

- “Undo” or rollback behavior (if relevant)

Anything else can be explicitly deferred as out-of-scope notes.

What does good acceptance criteria look like in practice?

Use testable statements anyone can run without guessing:

- Given a starting state

- When the user does X

- Then Y happens

Include at least one failure case and one permission rule. If a criterion can’t be tested, rewrite it until it can.

How minimal should a UI plan be for a scoped task?

Name the exact screens and the one visible change per screen.

Also list the required UI states:

- Loading

- Empty

- Error (and whether retry exists)

- Success (toast/message/updated list)

Keep copy (button text, errors) in scope too, even if it’s placeholder text.

What’s the simplest way to draft an API/data plan without over-designing?

Keep the contract small: usually one read and one write is enough for v1.

Define:

- Inputs/outputs as plain objects (required vs optional fields)

- Common errors (not found, validation failed)

- Auth rule in one sentence (who can read/write)

Store facts; compute views when possible.

How should I prompt Claude Code to produce a scoped task and commit plan?

Ask for a boxed deliverable:

- Restated scope + acceptance checklist

- 3–7 commits, each unlocking one behavior

- Likely files touched per commit

- Quick test plan (happy path + one edge)

- Explicit out-of-scope list

Then re-prompt any vague wording like “make it cleaner” into measurable behavior.

How do I split a feature into small commits that are easy to review?

Default sequence:

- Data/model change (if needed) + tests

- API behavior + validation

- UI wiring with empty/error states

- Final polish only if required

Rule of thumb: one commit = one new user-visible behavior + a quick way to prove it works. Avoid bundling “while I’m here” refactors into the feature commits.