Oct 20, 2025·8 min

Claude Shannon’s Information Theory in Modern Digital Tech

Learn Claude Shannon’s core ideas—bits, entropy, and channel capacity—and how they power compression, error correction, reliable networks, and modern digital media.

Learn Claude Shannon’s core ideas—bits, entropy, and channel capacity—and how they power compression, error correction, reliable networks, and modern digital media.

You use Claude Shannon’s ideas every time you send a text, watch a video, or join Wi‑Fi. Not because your phone “knows Shannon,” but because modern digital systems are built around a simple promise: we can turn messy real‑world messages into bits, move those bits through imperfect channels, and still recover the original content with high reliability.

Information theory is the math of messages: how much choice (uncertainty) a message contains, how efficiently it can be represented, and how reliably it can be transmitted when noise, interference, and congestion get in the way.

There is math behind it, but you don’t need to be a mathematician to get the practical intuition. We’ll use everyday examples—like why some photos compress better than others, or why your call can sound fine even when the signal is weak—to explain the ideas without heavy formulas.

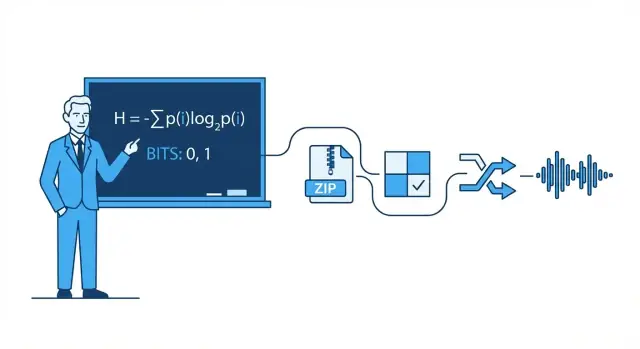

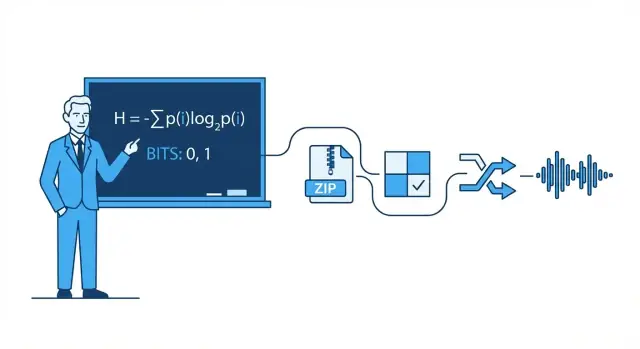

This article revolves around four Shannon-inspired pillars that show up across modern tech:

By the end, you should be able to think clearly about real tradeoffs: why higher video quality needs more bandwidth, why “more bars” doesn’t always mean faster internet, why some apps feel instant while others buffer, and why every system hits limits—especially the famous Shannon limit on how much reliable data a channel can carry.

In 1948, mathematician and engineer Claude Shannon published a paper with an unassuming title—A Mathematical Theory of Communication—that quietly rewired how we think about sending data. Instead of treating communication as an art, he treated it as an engineering problem: a source produces messages, a channel carries them, noise corrupts them, and a receiver tries to reconstruct what was sent.

Shannon’s key move was to define information in a way that’s measurable and useful for machines. In his framework, information isn’t about how important a message feels, what it means, or whether it’s true. It’s about how surprising it is—how much uncertainty gets removed when you learn the outcome.

If you already know what’s going to happen, the message carries almost no information. If you’re genuinely unsure, learning the result carries more.

To measure information, Shannon popularized the bit (short for binary digit). A bit is the amount of information needed to resolve a simple yes/no uncertainty.

Example: If I ask “Is the light on?” and you have no idea beforehand, the answer (yes or no) can be thought of as delivering 1 bit of information. Many real messages can be broken into long sequences of these binary choices, which is why everything from text to photos to audio can be stored and transmitted as bits.

This article focuses on the practical intuition behind Shannon’s ideas and why they show up everywhere: compression (making files smaller), error correction (fixing corruption), network reliability (retries and throughput), and channel capacity (how fast you can send data over a noisy link).

What it won’t do is walk through heavy proofs. You don’t need advanced math to understand the punchline: once you can measure information, you can design systems that approach the best possible efficiency—often surprisingly close to the theoretical limits Shannon described.

Before talking about entropy, compression, or error correction, it helps to pin down a few everyday terms. Shannon’s ideas are easier when you can name the pieces.

A symbol is one “token” from a set you’ve agreed on. That set is the alphabet. In English text, the alphabet might be letters (plus space and punctuation). In a computer file, the alphabet could be byte values 0–255.

A message is a sequence of symbols from that alphabet: a word, a sentence, a photo file, or a stream of audio samples.

To keep things concrete, imagine a tiny alphabet: {A, B, C}. A message could be:

A A B C A B A ...

A bit is a binary digit: 0 or 1. Computers store and transmit bits because hardware can reliably distinguish two states.

A code is a rule for representing symbols using bits (or other symbols). For example, with our {A, B, C} alphabet, one possible binary code is:

Now any message made of A/B/C can be turned into a stream of bits.

These terms are often mixed up:

Real messages aren’t random: some symbols appear more often than others. Suppose A happens 70% of the time, B 20%, C 10%. A good compression scheme will typically give shorter bit patterns to common symbols (A) and longer ones to rare symbols (C). That “unevenness” is what later sections will quantify with entropy.

Shannon’s most famous idea is entropy: a way to measure how much “surprise” is in a source of information. Not surprise as emotion—surprise as unpredictability. The more unpredictable the next symbol is, the more information it carries when it arrives.

Imagine you’re watching coin flips.

This “average surprise” framing matches everyday patterns: a text file with repeated spaces and common words is easier to predict than a file of random characters.

Compression works by assigning shorter codes to common symbols and longer codes to rare ones. If the source is predictable (low entropy), you can lean heavily on short codes most of the time and save space. If it’s close to random (high entropy), there’s less room to shrink it because nothing shows up often enough to exploit.

Shannon showed that entropy sets a conceptual benchmark: it’s the best possible lower bound on the average number of bits per symbol you can achieve when encoding data from that source.

Important: entropy is not a compression algorithm. It doesn’t tell you exactly how to compress a file. It tells you what’s theoretically possible—and when you’re already close to the limit.

Compression is what happens when you take a message that could be described in fewer bits, and you actually do it. Shannon’s key insight is that data with lower entropy (more predictability) has “room” to shrink, while high-entropy data (close to random) doesn’t.

Repeated patterns are the obvious win: if a file contains the same sequences over and over, you can store the sequence once and reference it many times. But even without clear repeats, skewed symbol frequencies help.

If a text uses “e” far more often than “z,” or a log file repeats the same timestamps and keywords, you don’t need to spend the same number of bits on every character. The more uneven the frequencies, the more predictable the source—and the more compressible it is.

A practical way to exploit skewed frequencies is variable-length coding:

Done carefully, this reduces the average bits per symbol without losing information.

Real-world lossless compressors often mix multiple ideas, but you’ll commonly hear these families:

Lossless compression reproduces the original perfectly (e.g., ZIP, PNG). It’s essential for software, documents, and anything where a single wrong bit matters.

Lossy compression deliberately discards information people usually don’t notice (e.g., JPEG photos, MP3/AAC audio). The goal shifts from “same bits back” to “same experience,” often achieving much smaller files by removing perceptually minor details.

Every digital system rests on a fragile assumption: a 0 stays a 0, and a 1 stays a 1. In reality, bits can flip.

In transmission, electrical interference, weak Wi‑Fi signals, or radio noise can nudge a signal over a threshold so a receiver interprets it incorrectly. In storage, tiny physical effects—wear in flash memory, scratches on optical media, even stray radiation—can change a stored charge or magnetic state.

Because errors are inevitable, engineers intentionally add redundancy: extra bits that don’t carry “new” information, but help you detect or repair damage.

Parity bit (quick detection). Add one extra bit so the total number of 1s is even (even parity) or odd (odd parity). If a single bit flips, the parity check fails.

Checksum (better detection for chunks). Instead of one bit, compute a small summary number from a packet or file (e.g., additive checksum, CRC). The receiver recomputes and compares.

Repetition code (simple correction). Send each bit three times: 0 becomes 000, 1 becomes 111. The receiver uses majority vote.

Error detection answers: “Did anything go wrong?” It’s common when retries are cheap—like network packets that can be resent.

Error correction answers: “What were the original bits?” It’s used when retries are expensive or impossible—like streaming audio over a noisy link, deep-space communication, or reading data from storage where re-reading might still produce errors.

Redundancy feels wasteful, but it’s the reason modern systems can be fast and trustworthy despite imperfect hardware and noisy channels.

When you send data over a real channel—Wi‑Fi, cellular, a USB cable, even a hard drive—noise and interference can flip bits or blur symbols. Shannon’s big promise was surprising: reliable communication is possible, even over noisy channels, as long as you don’t try to push too much information through.

Channel capacity is the channel’s “speed limit” for information: the maximum rate (bits per second) you can transmit with errors driven arbitrarily close to zero, given the channel’s noise level and constraints like bandwidth and power.

It’s not the same as the raw symbol rate (how fast you toggle a signal). It’s about how much meaningful information survives after noise—once you include smart encoding, redundancy, and decoding.

The Shannon limit is the practical name people give to this boundary: below it, you can (in theory) make communication as reliable as you want; above it, you can’t—errors remain no matter how clever your design is.

Engineers spend a lot of effort getting closer to the limit with better modulation and error-correcting codes. Modern systems like LTE/5G and Wi‑Fi use advanced coding so they can operate near this boundary instead of wasting huge amounts of signal power or bandwidth.

Think of it like packing items into a moving truck on a bumpy road:

Shannon didn’t hand us a single “best code,” but he proved the limit exists—and that striving toward it is worth it.

Shannon’s noisy-channel theorem is often summarized as a promise: if you send data below a channel’s capacity, there exist codes that can make errors arbitrarily rare. Real engineering is about turning that “existence proof” into practical schemes that fit into chips, batteries, and deadlines.

Most real systems use block codes (protect a chunk of bits at a time) or stream-oriented codes (protect an ongoing sequence).

With block codes, you add carefully designed redundancy to each block so the receiver can detect and correct mistakes. With interleaving, you reshuffle the order of transmitted bits/symbols so that a burst of noise (many errors in a row) is spread out into smaller, correctable errors across multiple blocks—crucial for wireless and storage.

Another big divider is how the receiver “decides” what it heard:

Soft decisions feed more information into the decoder and can significantly improve reliability, especially in Wi‑Fi and cellular.

From deep-space communication (where retransmission is expensive or impossible) to satellites, Wi‑Fi, and 5G, error-correcting codes are the practical bridge between Shannon’s theory and the reality of noisy channels—trading extra bits and computation for fewer dropped calls, faster downloads, and more reliable links.

The internet works even though individual links are imperfect. Wi‑Fi fades, mobile signals get blocked, and copper and fiber still suffer noise, interference, and occasional hardware glitches. Shannon’s core message—noise is inevitable, but reliability is still achievable—shows up in networking as a careful mix of error detection/correction and retransmission.

Data is split into packets so the network can route around trouble and recover from losses without resending everything. Each packet carries extra bits (headers and checks) that help the receiver decide whether what arrived is trustworthy.

A common pattern is ARQ (Automatic Repeat reQuest):

When a packet is wrong, you have two main choices:

FEC can reduce delays on links where retransmissions are expensive (high latency, intermittent loss). ARQ can be efficient when losses are rare, because you don’t “tax” every packet with heavy redundancy.

Reliability mechanisms consume capacity: extra bits, extra packets, and extra waiting. Retransmissions increase load, which can worsen congestion; congestion in turn increases delay and loss, triggering even more retries.

Good networking design aims for a balance: enough reliability to deliver correct data, while keeping overhead low so the network can maintain healthy throughput under varying conditions.

A useful way to understand modern digital systems is as a pipeline with two jobs: make the message smaller and make the message survive the journey. Shannon’s key insight was that you can often think about these as separate layers—even if real products sometimes blur them.

You start with a “source”: text, audio, video, sensor readings. Source coding removes predictable structure so you don’t waste bits. That could be ZIP for files, AAC/Opus for audio, or H.264/AV1 for video.

Compression is where entropy shows up in practice: the more predictable the content, the fewer bits you need on average.

Then the compressed bits must cross a noisy channel: Wi‑Fi, cellular, fiber, a USB cable. Channel coding adds carefully designed redundancy so the receiver can detect and correct errors. This is the world of CRCs, Reed–Solomon, LDPC, and other forward error correction (FEC) methods.

Shannon showed that, in theory, you can design source coding to approach the best possible compression, and channel coding to approach the best possible reliability up to channel capacity—independently.

In practice, this separation is still a great way to debug systems: if performance is bad, you can ask whether you’re losing efficiency in compression (source coding), losing reliability on the link (channel coding), or paying too much latency with retries and buffering.

When you stream video, the app uses a codec to compress frames. Over Wi‑Fi, packets may be lost or corrupted, so the system adds error detection, sometimes FEC, and then uses retries (ARQ) when needed. If the connection worsens, the player may switch to a lower bitrate stream.

Real systems blur the separation because time matters: waiting for retries can cause buffering, and wireless conditions can change quickly. That’s why streaming stacks combine compression choices, redundancy, and adaptation together—not perfectly separated, but still guided by Shannon’s model.

Information theory gets quoted a lot, and a few ideas get oversimplified along the way. Here are common misunderstandings—and the real tradeoffs engineers make when building compression, storage, and networking systems.

In everyday speech, “random” can mean “messy” or “unpredictable.” Shannon entropy is narrower: it measures surprise given a probability model.

So entropy isn’t a vibe; it’s a number tied to assumptions about how the source behaves.

Compression removes redundancy. Error correction often adds redundancy on purpose so the receiver can fix mistakes.

That creates a practical tension:

Shannon’s channel capacity says every channel has a maximum reliable throughput under given noise conditions. Below that limit, error rates can be made extremely small with the right coding; above it, errors become unavoidable no matter how clever you are.

This is why “perfectly reliable at any speed” isn’t possible: pushing speed up usually means accepting higher error probability, higher latency (more retransmissions), or more overhead (stronger coding).

When evaluating a product or architecture, ask:

Getting these four right matters more than memorizing formulas.

Shannon’s core message is that information can be measured, moved, protected, and compressed using a small set of ideas.

Modern networks and storage systems are essentially constant tradeoffs among rate, reliability, latency, and compute.

If you’re building real products—APIs, streaming features, mobile apps, telemetry pipelines—Shannon’s framework is a useful design checklist: compress what you can, protect what you must, and be explicit about the latency/throughput budget. One place this shows up immediately is when you prototype end-to-end systems quickly and then iterate: with a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai, teams can spin up a React web app, a Go backend with PostgreSQL, and even a Flutter mobile client from a chat-driven spec, then test real-world tradeoffs (payload size, retries, buffering behavior) early. Features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback make it easier to experiment with “stronger reliability vs. lower overhead” changes without losing momentum.

Deeper reading pays off for:

To keep going, browse related explainers in /blog, then check /docs for how our product exposes communication and compression-related settings and APIs. If you’re comparing plans or throughput limits, /pricing is the next stop.

Shannon’s key move was defining information as uncertainty reduced, not as meaning or importance. That makes information measurable, which lets engineers design systems that:

A bit is the amount of information needed to resolve a yes/no uncertainty. Digital hardware can reliably distinguish two states, so many different kinds of data can be turned into long sequences of 0s and 1s (bits) and treated uniformly for storage and transmission.

Entropy is a measure of average unpredictability in a source. It matters because unpredictability predicts compressibility:

Entropy is not a compressor; it’s a benchmark for what’s possible on average.

Compression reduces size by exploiting patterns and uneven symbol frequencies.

Text, logs, and simple graphics often compress well; encrypted or already-compressed data often doesn’t.

Encoding is just converting data into a chosen representation (e.g., UTF-8, mapping symbols to bits).

Compression is encoding that reduces the average number of bits by exploiting predictability.

Encryption is scrambling data with a key for secrecy; it typically makes data look random, which usually makes it harder to compress.

Because real channels and storage are imperfect. Interference, weak signals, hardware wear, and other effects can flip bits. Engineers add redundancy so receivers can:

That “extra” data is what buys reliability.

Error detection tells you something is wrong (common when resending is possible, like packets on the internet).

Error correction tells you what the original data was (useful when resending is expensive or impossible, like streaming links, satellites, or storage).

Many systems combine them: detect most issues quickly, correct some locally, and retransmit when needed.

Channel capacity is the maximum rate (bits/sec) you can send with error rates driven arbitrarily low, given noise and constraints.

The Shannon limit is the practical “speed limit” implication:

So better “signal bars” don’t automatically mean higher throughput if you’re already near other limits (congestion, interference, coding choices).

Networks split data into packets and use a mix of:

Reliability isn’t free: retries and extra bits reduce usable throughput, especially under congestion or poor wireless conditions.

Because you’re trading among rate, reliability, latency, and overhead:

Streaming systems often adapt bitrate and protection based on changing Wi‑Fi/cellular conditions to stay on the best point of that tradeoff.