Aug 14, 2025·7 min

Compiler approach to web performance: Rich Harris's view

A practical look at the compiler approach to web performance, contrasting runtime-heavy frameworks with compile-time output, plus a simple decision framework.

A practical look at the compiler approach to web performance, contrasting runtime-heavy frameworks with compile-time output, plus a simple decision framework.

Users rarely describe performance in technical terms. They say the app feels heavy. Pages take a beat too long to show anything, buttons respond late, and simple actions like opening a menu, typing in a search box, or switching tabs stutter.

The symptoms are familiar: a slow first load (blank or half-built UI), laggy interactions (clicks that land after a pause, jittery scrolling), and long spinners after actions that should feel instant, like saving a form or filtering a list.

A lot of this is runtime cost. In plain terms, it’s the work the browser has to do after the page loads to make the app usable: download more JavaScript, parse it, run it, build the UI, attach handlers, and then keep doing extra work on every update. Even on fast devices, there’s a limit to how much JavaScript you can push through the browser before the experience starts to drag.

Performance problems also show up late. Early on, the app is small: a few screens, light data, simple UI. Then the product grows. Marketing adds trackers, design adds richer components, teams add state, features, dependencies, and personalization. Each change looks harmless on its own, but the total work adds up.

That’s why teams start paying attention to compiler-first performance ideas. The goal usually isn’t perfect scores. It’s to keep shipping without the app getting slower every month.

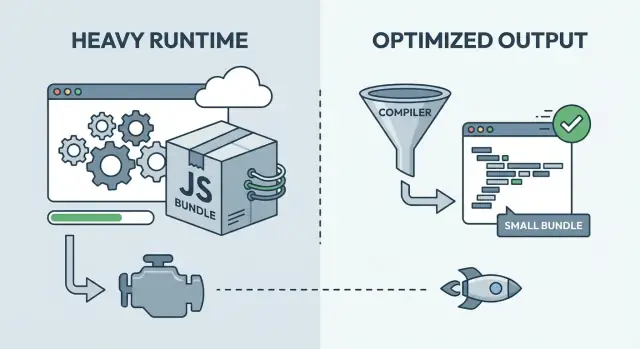

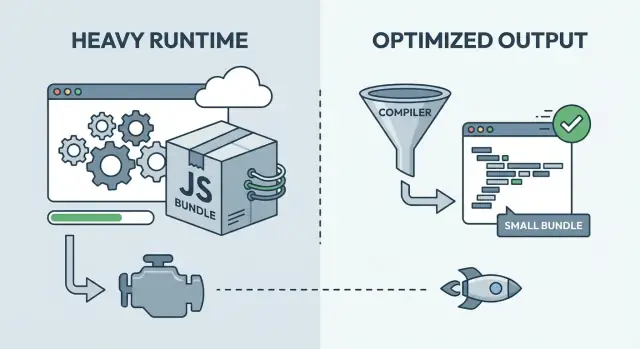

Most frontend frameworks help you do two things: build an app, and keep the UI in sync with data. The key difference is when the second part happens.

With a runtime-heavy framework, more of the work happens in the browser after the page loads. You ship a general-purpose runtime that can handle many cases: tracking changes, deciding what should update, and applying those updates. That flexibility can be great for development, but it often means more JavaScript to download, parse, and execute before the UI feels ready.

With compile-time optimization, more of that work moves into the build step. Instead of sending the browser a big set of rules, the build tool analyzes your components and generates more direct, app-specific code.

A useful mental model:

Most real products sit somewhere in the middle. Compiler-first approaches still ship some runtime code (routing, data fetching, animations, error handling). Runtime-heavy frameworks also lean on build-time techniques (minification, code splitting, server rendering) to reduce client work. The practical question isn’t which camp is “right,” but which mix fits your product.

Rich Harris is one of the clearest voices behind compiler-first frontend thinking. His argument is straightforward: do more work ahead of time so users download less code and the browser does less work.

The motivation is practical. Many runtime-heavy frameworks ship a general-purpose engine: component logic, reactivity, diffing, scheduling, and helpers that have to work for every possible app. That flexibility costs bytes and CPU. Even when your UI is small, you can still pay for a big runtime.

A compiler approach flips the model. During build time, the compiler looks at your actual components and generates the specific DOM update code they need. If a label never changes, it becomes plain HTML. If only one value changes, only the update path for that value is emitted. Instead of shipping a generic UI machine, you ship the output tailored to your product.

That often leads to a simple outcome: less framework code sent to users, and less work done on every interaction. It also tends to show up most on low-end devices, where extra runtime overhead becomes visible fast.

Tradeoffs still matter:

A practical rule of thumb: if your UI is mostly knowable at build time, a compiler can generate tight output. If your UI is highly dynamic or plugin-driven, a heavier runtime can be easier.

Compile-time optimization changes where the work happens. More decisions get made during the build, and less work is left for the browser.

One visible result is less JavaScript shipped. Smaller bundles reduce network time, parsing time, and the delay before the page can respond to a tap or click. On mid-range phones, that matters more than many teams expect.

Compilers can also generate more direct DOM updates. When the build step can see a component’s structure, it can produce update code that touches only the DOM nodes that actually change, without as many layers of abstraction on every interaction. This can make frequent updates feel snappier, especially in lists, tables, and forms.

Build-time analysis can also strengthen tree-shaking and dead-code removal. The payoff isn’t just smaller files. It’s fewer code paths the browser has to load and execute.

Hydration is another area where build-time choices can help. Hydration is the step where a server-rendered page becomes interactive by attaching event handlers and rebuilding enough state in the browser. If the build can mark what needs interactivity and what doesn’t, you can reduce first-load work.

As a side effect, compilation often improves CSS scoping. The build can rewrite class names, remove unused styles, and reduce cross-component style leakage. That lowers surprise costs as the UI grows.

Picture a dashboard with filters and a large data table. A compiler-first approach can keep the initial load lighter, update only the cells that changed after a filter click, and avoid hydrating parts of the page that never become interactive.

A bigger runtime isn’t automatically bad. It often buys flexibility: patterns decided at runtime, lots of third-party components, and workflows tested over years.

Runtime-heavy frameworks shine when the UI rules change often. If you need complex routing, nested layouts, rich forms, and a deep state model, a mature runtime can feel like a safety net.

A runtime helps when you want the framework to handle a lot while the app is running, not just while it’s being built. That can make teams faster day to day, even if it adds overhead.

Common wins include a large ecosystem, familiar patterns for state and data fetching, strong dev tools, easier plugin-style extension, and smoother onboarding when you’re hiring from a common talent pool.

Team familiarity is a real cost and a real benefit. A slightly slower framework that your team can ship with confidently can beat a faster approach that needs retraining, stricter discipline, or custom tooling to avoid footguns.

Many “slow app” complaints aren’t caused by the framework runtime. If your page is waiting on a slow API, heavy images, too many fonts, or third-party scripts, switching frameworks won’t fix the core issue.

An internal admin dashboard behind a login often feels fine even with a larger runtime, because users are on strong devices and the work is dominated by tables, permissions, and backend queries.

“Fast enough” can be the right target early on. If you’re still proving product value, keep iteration speed high, set basic budgets, and only take on compiler-first complexity when you have evidence it matters.

Iteration speed is time-to-feedback: how quickly someone can change a screen, run it, see what broke, and fix it. Teams that keep this loop short ship more often and learn faster. That’s why runtime-heavy frameworks can feel productive early: familiar patterns, quick results, lots of built-in behavior.

Performance work slows that loop when it’s done too early or too broadly. If every pull request turns into micro-optimization debates, the team stops taking risks. If you build a complex pipeline before you know what the product is, people spend time fighting tooling instead of talking to users.

The trick is agreeing on what “good enough” means and iterating inside that box. A performance budget gives you that box. It’s not about chasing perfect scores. It’s about limits that protect the experience while keeping development moving.

A practical budget might include:

If you ignore performance, you usually pay later. Once a product grows, slowness gets tied to architecture decisions, not just small tweaks. A late rewrite can mean freezing features, retraining the team, and breaking workflows that used to work.

Compiler-first tooling can shift this tradeoff. You may accept slightly longer builds, but you reduce the amount of work done on every device, every visit.

Revisit budgets as the product proves itself. Early on, protect the basics. As traffic and revenue grow, tighten the budgets and invest where the changes move real metrics, not pride.

Performance arguments get messy when nobody agrees on what “fast” means. Pick a small set of metrics, write them down, and treat them as a shared scoreboard.

A simple starter set:

Measure on representative devices, not just a development laptop. A fast CPU, warm cache, and local server can hide delays that show up on a mid-range phone over average mobile data.

Keep it grounded: pick two or three devices that match real users and run the same flow each time (home screen, login, a common task). Do that consistently.

Before you change frameworks, capture a baseline. Take today’s build, record the numbers for the same flows, and keep them visible. That baseline is your before photo.

Don’t judge performance by a single lab score. Lab tools help, but they can reward the wrong thing (great first load) while missing what users complain about (janky menus, slow typing, delays after the first screen).

When numbers get worse, don’t guess. Check what shipped, what blocked rendering, and where time went: network, JavaScript, or API.

To make a calm, repeatable choice, treat framework and rendering decisions like product decisions. The goal isn’t best tech. It’s the right balance between performance and the pace your team needs.

A thin slice should include the messy parts: real data, auth, and your slowest screen.

If you want a quick way to prototype that thin slice, Koder.ai (koder.ai) lets you build web, backend, and mobile app flows through chat, then export the source code. That can help you test a real route early and keep experiments reversible with snapshots and rollback.

Document the decision in plain language, including what would make you revisit it (traffic growth, mobile share, SEO goals). That makes the choice durable when the team changes.

Performance decisions usually go wrong when teams optimize what they can see today, not what users will feel in three months.

One mistake is over-optimizing in week one. A team spends days shaving milliseconds off a page that’s still changing daily, while the real problem is that users don’t yet have the right features. Early on, speed up learning first. Lock in deeper performance work once routes and components stabilize.

Another is ignoring bundle growth until it hurts. Things feel fine at 200 KB, then a few “small” additions later you’re shipping megabytes. A simple habit helps: track bundle size over time and treat sudden jumps like bugs.

Teams also default to client-only rendering for everything, even when some routes are mostly static (pricing pages, docs-style content, onboarding steps). Those pages can often be delivered with far less work on the device.

A quieter killer is adding a big UI library for convenience without measuring its cost in production builds. Convenience is valid. Just be clear about what you’re paying for in extra JavaScript, extra CSS, and slower interactions on mid-range phones.

Finally, mixing approaches without clear boundaries creates hard-to-debug apps. If half the app assumes compiler-generated updates while the other half relies on runtime magic, you end up with unclear rules and confusing failures.

A few guardrails that hold up in real teams:

Imagine a 3-person team building a SaaS for scheduling and billing. It has two faces: a public marketing site (landing pages, pricing, docs) and an authenticated dashboard (calendar, invoices, reports, settings).

With a runtime-first path, they pick a runtime-heavy setup because it makes UI changes quick. The dashboard becomes a big client-side app with reusable components, a state library, and rich interactions. Iteration is fast. Over time, the first load starts feeling heavy on mid-range phones.

With a compiler-first path, they choose a framework that pushes more work to build time to reduce client JavaScript. Common flows like opening the dashboard, switching tabs, and searching feel snappier. The tradeoff is that the team needs to be more deliberate about patterns and tooling, and some easy runtime tricks aren’t as drop-in.

What triggers change is rarely taste. It’s usually pressure from reality: slower pages hurt signups, more users show up on low-end devices, enterprise buyers ask for predictable budgets, the dashboard becomes always open and memory matters, or support tickets mention slowness on real networks.

A hybrid option often wins. Keep marketing pages lean (server-rendered or mostly static, minimal client code) and accept more runtime in the dashboard where interactivity pays for itself.

Using the decision steps: they name the critical journeys (signup, first invoice, weekly reporting), measure them on a mid-range phone, set a budget, and pick hybrid. Compiler-first defaults for public pages and shared components, runtime-heavy only where it clearly improves experimentation speed.

The easiest way to make these ideas real is a short weekly loop.

Start with a 15-minute scan: is bundle size trending up, which routes feel slow, what the biggest UI pieces are on those routes (tables, charts, editors, maps), and which dependencies contribute the most. Then pick one bottleneck you can fix without rewriting your stack.

For this week, keep it small:

To keep choices reversible, draw clear boundaries between routes and features. Prefer modules you can swap later (charts, rich text editors, analytics SDKs) without touching the whole app.

Most of the time it’s not the network alone—it’s runtime cost: the browser downloading, parsing, and executing JavaScript, building the UI, and doing extra work on every update.

That’s why an app can feel “heavy” even on a good laptop once the JavaScript workload gets large.

They’re the same goal (do less on the client), but the mechanism differs.

It means the framework can analyze your components at build time and output code tailored to your app, instead of shipping a big, generic UI engine.

The practical benefit is usually smaller bundles and less CPU work during interactions (clicks, typing, scrolling).

Start with:

Measure the same user flow each time so you can compare builds reliably.

Yes. If your app is waiting on slow APIs, huge images, too many fonts, or third-party scripts, a new framework won’t remove those bottlenecks.

Treat framework choice as one lever. First confirm where the time goes: network, JavaScript CPU, rendering, or backend.

Choose runtime-heavy when you need flexibility and iteration speed:

If the runtime isn’t your bottleneck, the convenience can be worth the extra bytes.

A simple default is:

Hybrid works best when you write down boundaries so the app doesn’t become a confusing mix of assumptions.

Use a budget that protects user feel without blocking shipping. For example:

Budgets are guardrails, not a contest for perfect scores.

Hydration is the work of taking a server-rendered page and making it interactive by attaching event handlers and rebuilding enough state in the browser.

If you hydrate too much, first load can feel slow even though HTML shows quickly. Build-time tooling can sometimes reduce hydration by marking what truly needs interactivity.

A good “thin slice” includes real-world mess:

If you’re prototyping that slice, Koder.ai can help you build the web + backend flow via chat and export the source, so you can measure and compare approaches early without committing to a full rewrite.