Sep 17, 2025·8 min

How to Create a Product Website That Grows With Use Cases

Learn how to design a product website that scales as new use cases appear—using modular pages, clear navigation, reusable content blocks, and a simple messaging system.

Learn how to design a product website that scales as new use cases appear—using modular pages, clear navigation, reusable content blocks, and a simple messaging system.

A product website “grows with use cases” when it can absorb new ways people use your product—without forcing you to rewrite your positioning, rebuild navigation, or duplicate half your content.

Use cases tend to expand in a few predictable directions:

The goal isn’t to create a page for every scenario. It’s to design a site where you can add a new use case as a “module”—a page, a section, a proof point—while keeping the overall story consistent.

That usually means:

As use cases grow, many sites drift into patterns that hurt clarity:

You’ll know your site structure can scale when:

Before you design new pages or rewrite your homepage, get clear on what “use cases” you actually need to support. A use-case inventory is a lightweight list of the situations people hire your product for—written in plain language, not product features.

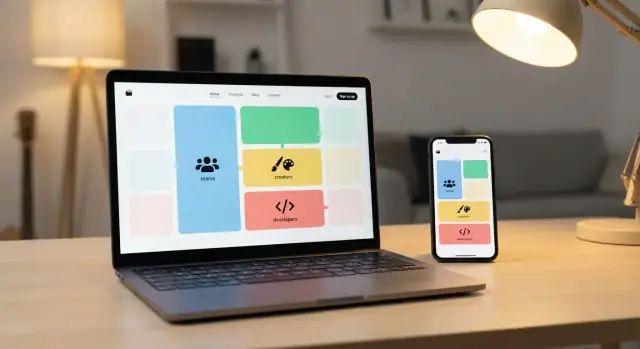

Start by grouping people into a few audience types you can recognize quickly. Keep it simple—3–6 groups is plenty.

Consider:

The goal isn’t a perfect segmentation model; it’s a shared vocabulary your team can use when creating or expanding use-case pages later.

For each audience type, write down the “job” they’re trying to accomplish and what success looks like. Focus on outcomes, not buttons.

Examples of outcome language:

Different audiences need different information at each step:

Use real customer language to avoid guesswork. Pull from sales call notes, support tickets, onboarding questions, and common objections. These become the raw ingredients for use-case page copy, FAQs, and proof points.

A use-case-driven site grows fast. Without a reusable messaging framework, every new page invents its own language—and visitors start wondering if they’re even looking at the same product. A framework gives you consistency without making everything sound generic.

Your core promise is the sentence every use-case page should be able to “inherit.” Keep it simple:

For [who it’s for], we help you [achieve outcome] without [common pain].

Example pattern: “For operations teams, we reduce manual handoffs so work moves faster with fewer errors.”

Pick proof points that can be reused across audiences, then selectively emphasized per use case. These can be:

Write each proof point as a benefit-first line, then back it up with a short “because…” clause.

Your tagline should be memorable and outcome-focused (6–10 words). Then add a short paragraph (2–4 sentences) that explains what the product is, who it’s for, and where it fits in a workflow.

Use this pair everywhere: homepage hero, product pages, use-case intros, sales decks.

Consistency builds trust and improves scanning. Make a small glossary that includes:

This is how you scale messaging without rewriting it every time you add a new page.

A product website that adds use cases over time needs structure that stays understandable as the menu grows. The goal isn’t to predict every future page—it’s to choose organizing principles that remain stable when you double the number of use cases.

Your homepage should guide people into a small set of predictable routes. Choose paths that match how prospects self-identify:

Keep it to one primary model if you can. If you must mix, make the second model clearly secondary (below the fold or in a submenu) so visitors don’t feel forced to “solve” your navigation.

These labels can overlap, so define them clearly:

A simple rule: if a page changes mainly by customer context, it’s an Industry. If it changes mainly by desired result, it’s a Use case.

Start with core pages that will stay true over time (top categories and a few “anchor” pages). Then add deeper pages underneath as you learn.

Example hierarchy:

Aim for predictable categories and avoid burying key pages behind multiple layers. If someone can’t guess where a page lives, the structure is too clever. Shallow navigation also makes it easier to add new use cases without rearranging your whole site.

If your website needs to support more and more use cases over time, the fastest way to stay consistent is to stop treating each new page as a one-off design project. Instead, define a small set of page types and build templates you can reuse with minimal debate.

Most product sites can be covered with a clear, limited menu of templates:

Each type should have a purpose, a primary audience, and a “success action” (e.g., book a demo, start a trial, request pricing).

Build pages from the same set of modules so you can mix and match without redesigning:

This keeps new use case pages fast to publish, and it helps visitors recognize the structure as they browse.

A template only scales if the rules are written down. Create simple guidelines like:

When a new use case appears, your team should be able to publish it by filling in modules—not reinventing the page.

Use-case pages work best when they feel “made for me” to the reader—without boxing your product into a tiny corner. The trick is to be precise about the outcome and audience, while keeping the underlying story reusable.

Pick one naming formula and stick with it. A reliable option is Outcome + Audience, such as “Faster reporting for ops teams.” It signals value immediately, and it prevents titles from drifting into vague labels like “Analytics” or overly narrow ones like “Reporting for warehouse ops in the Midwest.”

A good name answers two questions:

Consistency is what makes a growing library feel intentional. A simple flow that scales well is:

Problem → Approach → Outcomes → How it works

Keep each section tight. The goal is not to explain every feature; it’s to help someone recognize their situation and understand why your product is a fit.

Add a short “Who it’s for / not for” block. This helps qualified visitors self-select quickly and reduces noise from the wrong leads. Be direct but not harsh (e.g., “Best for teams with recurring reporting needs” / “Not ideal if you only run one-off reports a few times a year”).

Each use-case page should have:

Avoid stacking multiple competing buttons. When every page has a clear next step, your use-case library can expand without creating decision fatigue.

Proof is what turns a “sounds good” use case into a “this will work for me.” The trick is to make trust elements repeatable so every new use-case page doesn’t require starting from zero.

Aim for a mix you can apply across many use cases:

Not every page needs every type. What matters is that each use case has at least one strong, credible proof point.

Trust works best when it appears where a visitor is weighing risk:

Keep these elements compact. You’re reducing friction, not asking people to read a novel.

Create a simple “proof library” your team can pull from when new use cases are added. It can live in a doc, spreadsheet, or CMS collection, but it should include:

This prevents proof from being scattered across decks, emails, and old pages—and helps marketing, sales, and product stay consistent.

A scalable trust pattern is a small FAQ block tailored to that specific use case. Focus on common blockers like setup time, integrations, data security, and “Will this work for my team size?” Keep answers direct and avoid overpromising; clarity builds trust faster than hype.

A website that “grows with use cases” can’t rely on navigation alone. As you add more pages, visitors need clear paths between topics, and search engines need a predictable structure to understand what each page is about.

Pick a small set of URL buckets and stick to them. This makes future pages feel like they belong, and it reduces the chance you’ll need painful reorganizations later.

Common patterns that scale well:

Keep URLs short, lowercase, and based on the primary phrase of the page. Avoid dates, campaign names, or clever wording that won’t age well.

Each use-case page should act like a hub, connecting to the next most helpful step for that reader. Add internal links from use case → relevant:

Use natural anchor text (the clickable words) that describes what the reader will get, not generic “learn more.”

At the end (and sometimes mid-page), include a small “Related use cases” block. Make the selection purposeful:

Before publishing a new page, define its unique theme and primary keyword. If two pages target the same query (e.g., “customer onboarding automation”), merge them or differentiate clearly—such as “for startups” vs. “for enterprise,” or “for product-led onboarding” vs. “for sales-led onboarding.”

A site that supports many use cases will attract people at very different stages: some are just exploring, others are comparing options, and a few are ready to buy. If every page pushes the same action, you’ll either scare off early visitors or slow down motivated buyers.

Pick a few calls-to-action you can reuse across the site and apply them consistently:

Consistency helps visitors understand what happens next, and it reduces design and copy decisions when you add new pages.

Use the page’s job to decide the primary CTA:

Ask only what you need to route the request. Fewer fields means more completions. If you must qualify, do it after the first step (for example, during scheduling or in onboarding).

After someone clicks, don’t leave them guessing. Provide a clear next step:

These paths turn a click into progress, regardless of which audience found the page.

A website that can grow with new use cases needs feedback you can trust. If you don’t measure consistently, you’ll end up redesigning based on opinions, the loudest stakeholder, or the last sales call.

Start with a few events that map directly to business outcomes. At minimum, track:

Keep event names consistent across templates so you can compare pages fairly. The goal is not to measure everything—it’s to measure the actions that signal intent.

Use cases multiply quickly, so you need views that stay useful as the site expands. Create dashboards (or simple reports) that break performance down in two ways:

This helps you spot patterns—like use-case pages driving lots of CTA clicks but low form submits (a sign your form or follow-up promise needs work), or one segment converting better with a different CTA.

Numbers tell you what changed; qualitative feedback tells you why. Mix in:

Avoid constant tinkering. Use a predictable rhythm:

Treat big changes as experiments: document what you changed, why, and what success looks like before you ship.

A website that “grows with use cases” needs a gate—not to slow teams down, but to keep the experience coherent as new pages appear. Governance is simply the set of rules and routines that decide what gets added, where it lives, and how it stays accurate.

Treat every new use-case idea like a mini product request. Use a single form or doc so marketing, product, and sales speak the same language.

New use-case checklist

Avoid “exploding” your navigation as the list expands. Add a use case to primary navigation only when there’s repeatable demand (not a one-off deal) and it represents a meaningful audience you plan to keep serving. Everything else can live in secondary hubs, filters, or search.

Use cases naturally blur. Plan for sunsetting or merging pages when:

Maintain a content calendar tied to product releases, customer stories, and quarterly priorities. This prevents random additions and ensures updates land when the product and proof are strongest.

A website that can expand with new use cases is easier to build if you treat it like a product release: ship a solid “v1,” then add new pages without redesigning everything.

1) Audit (Week 1)

Capture current pages, repeated messages, missing questions, and which customer segments show up most in sales calls.

2) Templates (Week 2)

Define reusable page templates (homepage, solution/use-case page, industry page, integration page) plus shared components (hero, proof strip, FAQ, CTA).

3) Core pages (Week 3)

Publish the foundation: positioning, navigation, and conversion paths (e.g., product, pricing, security/trust, contact/demo, and a blog/news area).

4) Top 3 use cases (Weeks 4–5)

Create pages for the three highest-value use cases first. Treat them as the pattern library for future pages.

5) Expand (ongoing, monthly cadence)

Add 1–2 new use-case pages per month, based on demand, search interest, and pipeline impact.

Use a CMS your team can edit safely, a small design system (tokens + components), and a living content doc that defines structure, tone, and required sections for every new use-case page.

If your team wants to move faster from “template spec” to working pages, tools like Koder.ai can help: you can describe a modular React page structure in chat, iterate in a planning mode, and ship updates without hand-building every layout. It’s especially useful when you’re adding use-case pages on a monthly cadence and want consistent components, clean URLs, and repeatable CTAs—while still being able to export source code or deploy/host when you’re ready.

Agree on your top 3 use cases, pick one template, draft one use-case page end-to-end, and review it with sales. Then lock the template and start the monthly expansion cadence.

It means your site can add new scenarios—industries, roles, or workflows—without rewriting core positioning, reorganizing navigation, or duplicating lots of content. You’re expanding with repeatable modules (pages, sections, proof points) while keeping one consistent story.

Because it creates clutter and inconsistency:

A scalable approach keeps a stable narrative and adds specificity in structured, reusable ways.

Start with a lightweight inventory:

Use the “inheritance” test: every use-case page should clearly fit under one core promise:

For [who], we help you [outcome] without [pain].

If a new use case forces you to rewrite that sentence, it may be a different product category, a different ICP, or a sign your positioning is too broad.

Make the distinction explicit:

Rule of thumb: if the page changes mainly by context, it’s an industry page; if it changes mainly by desired result, it’s a use-case page.

Pick 1 primary model that matches how visitors self-identify (role, goal, or industry). Keep the other models secondary (below the fold, hubs, or submenus).

Aim for:

Use an Outcome + Audience pattern and keep it consistent, for example: “Faster reporting for ops teams.”

A good use-case title answers:

Avoid vague labels (“Analytics”) and overly narrow ones that won’t scale.

Use a repeatable structure such as:

Include a short Who it’s for / not for block to help visitors self-qualify, and keep CTAs consistent:

Standardize evidence so it’s easy to reuse:

Maintain a simple proof library (quotes, permissions, applicable segments) so new pages don’t start from zero.

Track a small set of consistent events across templates:

Then review performance:

Add qualitative input (polls, light testing, sales objections) and iterate on a cadence (monthly small fixes, quarterly structural changes).