Jun 13, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Centralized Metrics Ownership

Learn a practical blueprint for building a web app that centralizes metric definitions, owners, approvals, and reuse across teams.

Learn a practical blueprint for building a web app that centralizes metric definitions, owners, approvals, and reuse across teams.

Centralized metrics means your company has one shared place where business metrics are defined, owned, and explained—so everyone is working from the same playbook. In practice, it’s a metrics catalog (a KPI dictionary) where each metric has a single approved definition, an accountable owner, and clear guidance on how to use it.

Without a centralized definition, teams naturally create their own versions of the same KPI. “Active users” might mean “logged in” to Product, “did any event” to Analytics, and “paid subscribers who used a feature” to Finance.

Each version can be reasonable in isolation—but when a dashboard, a quarterly business review, and a billing report disagree, trust erodes fast.

You also get hidden costs: duplicated work, long Slack threads to reconcile numbers, last-minute changes before exec reviews, and a growing pile of tribal knowledge that breaks when people switch roles.

A centralized metrics app creates a single source of truth for:

This is not about forcing one number for every question—it’s about making differences explicit, intentional, and discoverable.

You’ll know centralized metrics governance is working when you see fewer metric disputes, faster reporting cycles, fewer “which definition did you use?” follow-ups, and consistent KPIs across dashboards and meetings—even as the company scales.

Before you design screens or workflows, decide what the app is responsible for remembering. A centralized metrics app fails when definitions live in comments, spreadsheets, or people’s heads. Your data model should make every metric explainable, searchable, and safely changeable.

Most teams can cover the majority of use cases with these objects:

These objects make the catalog feel complete: users can jump from a metric to its slices, origin, steward, and where it appears.

A metric page should answer: What is it? How is it calculated? When should I use it?

Include fields such as:

Even at the data model level, plan for governance:

Good catalogs are navigable:

If you get these objects and relationships right, your later UX (catalog browsing, metric pages, templates) becomes straightforward—and your definitions stay consistent as the company grows.

A centralized metrics app only works when every metric has a clear “adult in the room.” Ownership answers basic questions quickly: Who guarantees this definition is correct? Who approves changes? Who tells everyone what changed?

Metric owner

The accountable person for a metric’s meaning and use. Owners don’t need to write SQL, but they do need authority and context.

Steward / reviewer

A quality gatekeeper who checks that definitions follow standards (naming, units, segmentation rules, allowed filters), and that the metric aligns with existing metrics.

Contributor

Anyone who can propose a new metric or suggest edits (Product Ops, Analytics, Finance, Growth, etc.). Contributors move ideas forward, but they don’t ship changes on their own.

Consumer

The majority of users: people who read, search, and reference metrics in dashboards, docs, and planning.

Admin

Manages the system itself: permissions, role assignment, templates, and high-risk actions like forced ownership reassignment.

Owners are responsible for:

Set expectations directly in the UI so people don’t guess:

Make “unowned metric” a first-class state. A pragmatic path:

This structure prevents ghost metrics and keeps definitions stable as teams change.

A centralized metrics app works when it’s clear who can change a metric, how changes are evaluated, and what “approved” actually guarantees. A simple, reliable model is a status-driven workflow with explicit permissions and a visible paper trail.

Draft → Review → Approved → Deprecated should be more than labels—each status should control behavior:

Treat new metrics and changes as proposals. A proposal should capture:

A consistent checklist keeps reviews fast and fair:

Every transition should be logged: proposer, reviewers, approver, timestamps, and a diff of what changed. This history is what lets you confidently answer: “When did this KPI change, and why?” It also makes rollbacks safer when a definition causes surprises.

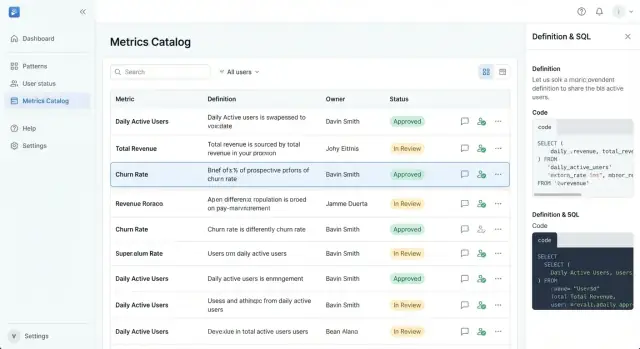

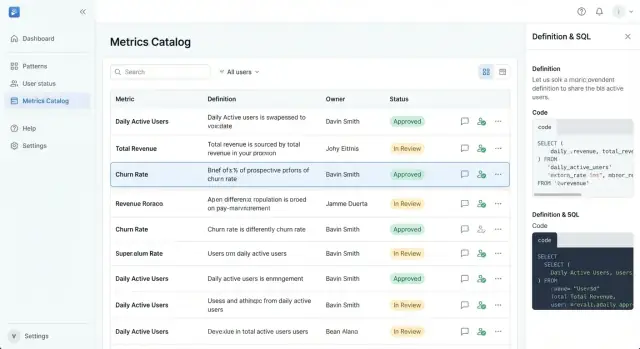

Your app succeeds or fails on whether someone can answer, in under a minute: “Is this metric real, current, and who owns it?” The UX should feel closer to a well-organized product catalog than a data tool.

Start with a catalog home that supports quick scanning and confident selection.

Make the primary navigation opinionated:

Each metric card/row should show the minimum decision set: metric name, short definition, status badge, owner, and last updated date. This prevents users from clicking into multiple pages just to figure out whether a metric is usable.

A metric page should be readable top-to-bottom like a spec sheet:

Keep technical content collapsible (“Show SQL / calculation details”) so non-technical users aren’t forced to parse it.

Templates reduce inconsistency. Use required fields (name, definition, owner, status, domain, numerator/denominator or formula) and provide suggested wording like “Count of…” or “Percentage of…”. Pre-fill examples to prevent blank, vague entries.

Write for clarity: avoid acronyms in titles, support synonyms (“Active Users” vs. “DAU”), and show tooltips for unavoidable jargon. Always pair a metric with a human owner—people trust people more than tables.

If a metrics app is where definitions become official, access control can’t be an afterthought. You’re not just protecting data—you’re protecting decisions: what counts as Revenue, who can change it, and when.

Start with a clear login approach and keep it consistent across the product:

Whichever you choose, make identity stable: users should have a unique ID even if their email changes.

Use role-based access control (RBAC) for broad permissions, and add resource-level ownership for precision.

A simple model:

Then layer in ownership rules like “Only the metric owner (or domain approver) can edit the approved definition.” This prevents drive-by edits while still enabling collaboration.

Some actions should require stronger checks because they alter trust:

Practical safeguards: confirmation dialogs with clear impact text, required reasons for changes, and (for sensitive actions) re-authentication or admin approval.

Add an admin area that supports real operations:

Even if your first release is small, designing these controls early prevents messy exceptions later—and makes metrics governance feel predictable instead of political.

When a metric changes, confusion spreads faster than the update. A centralized metrics app should treat every definition like a product release: versioned, reviewable, and easy to roll back (at least conceptually) if something goes wrong.

Create a new version whenever anything that could affect interpretation changes—definition text, calculation logic, included/excluded data, ownership, thresholds, or even the display name. “Minor edit” and “major edit” can exist, but both should be captured as versions so people can answer: Which definition did we use when we made that decision?

A practical rule: if a stakeholder might ask “did this metric change?”, it deserves a new version.

Each metric page should include a clear timeline that shows:

Approvals should be linked to the exact version they authorized.

Many metrics need definitions that change at a specific point in time (new pricing, new product packaging, a revised policy). Support effective dates so the app can show:

This avoids retroactively rewriting history and helps analysts align reporting periods correctly.

Deprecation should be explicit, not silent. When a metric is deprecated:

Done well, deprecation reduces duplicate KPIs while preserving context for old dashboards and past decisions.

A centralized metrics app only becomes the source of truth when it fits into how people already work: dashboards in BI, queries in the warehouse, and approvals in chat. Integrations turn definitions into something teams can trust and reuse.

Your metric page should answer a simple question: “Where is this number used?” Add a BI integration that lets users link a metric to dashboards, reports, or specific tiles.

This creates two-way traceability:

/bi/dashboards/123 if you proxy or store internal references).The practical win is faster audits and fewer debates: when a dashboard looks off, people can verify the definition rather than re-litigating it.

Most metric disagreements start in the query. Make the warehouse connection explicit:

You don’t need to execute queries in your app at first. Even static SQL plus lineage gives reviewers something concrete to validate.

Routing governance through email slows everything down. Post event notifications to Slack/Teams for:

Include a deep link back to the metric page and the specific action needed (review, approve, comment).

An API lets other systems treat metrics as a product, not a document. Prioritize endpoints for search, read, and status:

Add webhooks so tools can react in real time (e.g., trigger a BI annotation when a metric is deprecated). Document these at /docs/api, and keep payloads stable so automations don’t break.

Together, these integrations reduce tribal knowledge and keep metric ownership visible wherever decisions happen.

A metrics app only works when definitions are consistent enough that two people reading the same metric arrive at the same interpretation. Standards and quality checks turn “a page with a formula” into something teams can trust and reuse.

Start by standardizing the fields every metric must have:

Make these fields required in your metric template, not “recommended.” If a metric can’t meet the standard, it’s not ready to publish.

Most disagreements happen at the edges. Add a dedicated “Edge cases” section with prompts for:

Add structured validation fields so users know when a metric is healthy:

Before approval, require a checklist like:

The app should block submission or approval until all required items pass, turning quality from a guideline into a workflow.

A metrics catalog only works when it becomes the first stop for “What does this number mean?” Adoption is a product problem, not just a governance problem: you need clear value for everyday users, low-friction paths to contribute, and visible responsiveness from owners.

Instrument simple signals that tell you whether people are actually relying on the catalog:

Use these signals to prioritize improvements. For example, a high “no results” rate often means inconsistent naming or missing synonyms—fixable with better templates and curation.

People trust definitions more when they can ask questions in context. Add lightweight feedback where confusion happens:

Route feedback to the metric owner and steward, and show status (“triaged,” “in review,” “approved”) so users see progress rather than silence.

Adoption stalls when users don’t know how to contribute safely. Provide two prominent guides and link them from the empty state and the navigation:

Keep these as living pages (e.g., /docs/adding-a-metric and /docs/requesting-changes).

Set a weekly review meeting (30 minutes is enough) with owners and stewards to:

Consistency is the adoption flywheel: fast answers build trust, and trust drives repeat use.

Security for a metrics ownership app isn’t only about preventing breaches—it’s also about keeping the catalog trustworthy and safe for everyday sharing. The key is being clear about what belongs in the system, what doesn’t, and how changes are recorded.

Treat the app as a source of truth for meaning, not a repository of raw facts.

Store safely:

/dashboards/revenue)Avoid storing:

When teams want examples, use synthetic examples (“Order A, Order B”) or aggregate examples (“last week’s total”) with clear labels.

You’ll want an audit trail for compliance and accountability, but logs can accidentally become a data leak.

Log:

Don’t log:

Set retention by policy (for example, 90–180 days for standard logs; longer for audit events) and separate audit events from debug logs so you can keep the former without keeping everything.

Minimum expectations:

Begin with a pilot domain (e.g., Revenue or Acquisition) and 1–2 teams. Define success metrics such as “% of dashboards linked to approved metrics” or “time to approve a new KPI.” Iterate on friction points, then expand domain by domain with lightweight training and a clear expectation: if it’s not in the catalog, it’s not an official metric.

If you’re turning this into a real internal tool, the fastest path is usually to ship a thin but complete version—catalog browsing, metric pages, RBAC, and an approval workflow—then iterate.

Teams often use Koder.ai to get that first version live quickly: you can describe the app in chat, use Planning Mode to lock the scope, and generate a working stack (React on the frontend; Go + PostgreSQL on the backend). From there, snapshots and rollback help you iterate safely, and source code export keeps you unblocked if you want to take the codebase into your existing engineering pipeline. Deployment/hosting and custom domains are useful for internal rollouts, and the free/pro/business/enterprise tiers make it easy to start small and scale governance as adoption grows.

Centralized metrics means there’s one shared, approved place to define KPIs—typically a metrics catalog/KPI dictionary—so teams don’t maintain conflicting versions.

Practically, each metric has:

Start by inventorying the KPIs that appear in exec reviews, finance reporting, and top dashboards, then compare definitions side-by-side.

Common red flags:

Most teams get strong coverage with these objects:

Aim for fields that answer: What is it? How is it calculated? When should I use it?

A practical “required” set:

Use a status-driven workflow that controls what’s editable and what’s “official”:

Also store a proposal record capturing .

Define clear roles and tie them to permissions:

Version whenever a change could alter interpretation (definition, logic, filters, grain, thresholds, even renames).

Include a readable changelog:

Support effective dates so you can show current, upcoming, and past definitions without rewriting history.

Use RBAC + resource-level ownership:

Add extra friction for trust-sensitive actions (publish/approve, deprecate/delete, change ownership/permissions) using confirmation prompts and required reasons.

Start with integrations that reduce real day-to-day friction:

Treat adoption as a product rollout:

For security, store definitions and metadata, not raw customer data or secrets. Keep audit logs for changes/approvals, set retention policies, and ensure backups + restore tests are in place.

Model the relationships explicitly (e.g., dashboards use many metrics; metrics depend on multiple sources).

Make “unowned metric” a first-class state with escalation rules (auto-suggest → time-box → escalate to governance lead).