Jul 08, 2025·8 min

How to Create a Web App for Cross-Team Dependency Tracking

Learn how to plan and build a web app for cross-team dependency tracking: data model, UX, workflows, alerts, integrations, and rollout steps.

Learn how to plan and build a web app for cross-team dependency tracking: data model, UX, workflows, alerts, integrations, and rollout steps.

Before you design screens or choose a tech stack, get crisp on what “dependency” means in your organization. If people use the word to describe everything, your app will end up tracking nothing well.

Write a one-sentence definition everyone can repeat, then list what qualifies. Common categories include:

Also define what is not a dependency (e.g., “nice-to-have improvements,” general risks, or internal tasks that don’t block another team). This keeps the system clean.

Dependency tracking fails when it’s built only for PMs or only for engineers. Name your primary users and what each needs in 30 seconds:

Pick a small set of outcomes, like:

Capture the problems your app must solve on day one: stale spreadsheets, unclear owners, missed dates, hidden risks, and status updates scattered across chat threads.

Once you’re aligned on what you’re tracking and who it’s for, lock down the vocabulary and lifecycle. Shared definitions are what turn “a list of tickets” into a system that reduces blockers.

Pick a small set of types that covers most real situations, and make each type easy to recognize:

The goal is consistency: two people should classify the same dependency the same way.

A dependency record should be small but complete enough to manage:

If you allow creating a dependency without an owner team or due date, you’re building a “concern tracker,” not a coordination tool.

Use a simple state model that matches how teams actually work:

Proposed → Accepted → In progress → Ready → Delivered/Closed, plus Rejected.

Write down state-change rules. For example: “Accepted requires an owner team and an initial target date,” or “Ready requires evidence.”

For closure, require all of the following:

These definitions become the backbone of your filters, reminders, and status reviews later.

A dependency tracker succeeds or fails based on whether people can describe reality without fighting the tool. Start with a small set of objects that match how teams already talk, then add structure where it prevents confusion.

Use a handful of primary records:

Avoid creating separate types for every edge case. It’s better to add a few fields (e.g., “type: data/API/approval”) than split the model too early.

Dependencies often involve multiple groups and multiple tasks. Model this explicitly:

This prevents brittle “one dependency = one ticket” thinking and makes roll-up reporting possible.

Every primary object should include audit fields:

Not every dependency has a team in your org chart. Add an Owner/Contact record (name, org, email/Slack, notes) and allow dependencies to point to it. That keeps vendor or “other department” blockers visible without forcing them into your internal team structure.

If roles aren’t explicit, dependency tracking turns into a comment thread: everyone assumes someone else is responsible, and dates get “adjusted” without context. A clear role model keeps the app trustworthy and makes escalation predictable.

Start with four everyday roles and one administrative role:

Make the Owner required and singular: one dependency, one accountable owner. You can still support collaborators (contributors from other teams), but collaborators should never replace accountability.

Add an escalation path when an Owner doesn’t respond: first ping the Owner, then their manager (or team lead), then a program/release owner—based on your org’s structure.

Separate “editing details” from “changing commitments.” A practical default:

If you support private initiatives, define who can see them (e.g., only involved teams + Admin). Avoid “secret dependencies” that surprise delivery teams.

Don’t hide accountability in a policy doc. Show it on every dependency:

Labeling “Accountable vs Consulted” directly in the form reduces misrouting and makes status reviews faster.

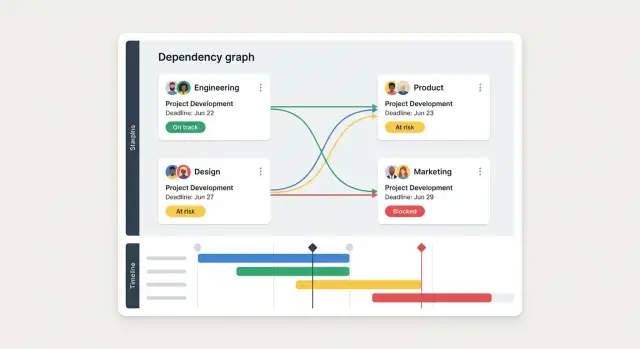

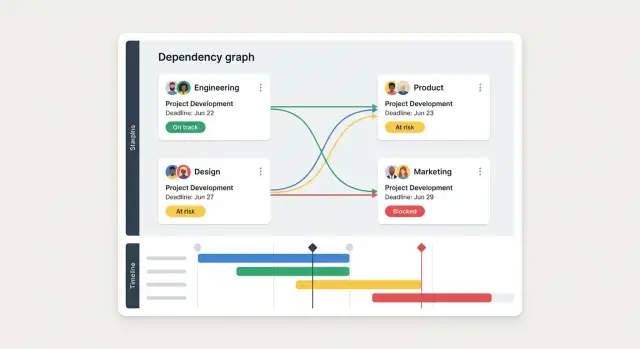

A dependency tracker only works if people can find their items in seconds and update them without thinking. Design around the most common questions: “What am I blocking?”, “What’s blocking me?”, and “Is anything about to slip?”

Start with a small set of views that match how teams talk about work:

Most tools fail at the “daily update.” Optimize for speed:

Use color plus text labels (never color alone) and keep the vocabulary consistent. Add a prominent “Last updated” timestamp on every dependency, and a stale warning when it hasn’t been touched for a defined period (for example, 7–14 days). This nudges updates without forcing meetings.

Every dependency should have a single thread that contains:

When the detail page tells the full story, status reviews become faster—and many “quick syncs” disappear because the answer is already written down.

A dependency tracker succeeds or fails on the everyday actions it supports. If teams can’t quickly request work, respond with a clear commitment, and close the loop with proof, your app turns into a “FYI board” instead of an execution tool.

Start with a single “Create request” flow that captures what the providing team needs to deliver, why it matters, and when it’s needed. Keep it structured: requested due date, acceptance criteria, and a link to the relevant epic/spec.

From there, enforce an explicit response state:

This avoids the most common failure mode: silent “maybe” dependencies that look fine until they blow up.

Define lightweight expectations in the workflow itself. Examples:

The goal isn’t policing; it’s keeping commitments current so planning stays honest.

Allow teams to set a dependency to At risk with a short note and next step. When someone changes a due date or status, require a reason (a dropdown + free text). This single rule creates an audit trail that makes retrospectives and escalations factual, not emotional.

“Close” should mean the dependency is satisfied. Require evidence: a link to a merged PR, released ticket, document, or an approval note. If closure is fuzzy, teams will “green” items early to reduce noise.

Support bulk updates during status reviews: select multiple dependencies and set the same status, add a shared note (e.g., “re-planned after Q1 reset”), or request updates. This keeps the app fast enough to use in real meetings, not just after them.

Notifications should protect delivery, not distract people. The easiest way to create noise is to alert everyone about everything. Instead, design alerts around decision points (someone needs to act) and risk signals (something is drifting).

Keep your first version focused on events that change the plan or require an explicit response:

Each trigger should map to a clear next step: accept/decline, propose a new date, add context, or escalate.

Default to in-app notifications (so alerts are tied to the dependency record) plus email for anything that can’t wait.

Offer optional chat integrations—Slack or Microsoft Teams—but treat them as delivery mechanisms, not the system of record. Chat messages should deep-link back to the item (for example, /dependencies/123) and include the minimum context: who needs to act, what changed, and by when.

Provide team-level and user-level controls:

This is also where “watchers” matter: notify the requester, the owning team, and any explicitly added stakeholders—avoid broad broadcasts.

Escalation should be automated but conservative: alert when a dependency is overdue, when the due date is pushed repeatedly, or when a blocked status has no update for a defined period.

Route escalations to the right level (team lead, program manager) and include the history so the recipient can act quickly without chasing context.

Integrations should eliminate re-entry, not add setup overhead. The safest approach is to start with the systems teams already trust (issue trackers, calendars, and identity), keep the first version read-only or one-way, then expand only after people rely on it.

Pick a primary tracker (Jira, Linear, or Azure DevOps) and support a simple link-first flow:

PROJ-123).This avoids “two sources of truth” while still giving dependency visibility. Later, add optional two-way sync for a small subset of fields (status, due date), with clear conflict rules.

Milestones and deadlines are often maintained in Google Calendar or Microsoft Outlook. Start by reading events into your dependency timeline (e.g., “Release Cutoff”, “UAT Window”) without writing anything back.

Read-only calendar sync lets teams keep planning where they already do it, while your app shows impacts and upcoming dates in one place.

Single sign-on reduces onboarding friction and permission drift. Choose based on customer reality:

If you’re early, ship one provider first and document how to request others.

Even non-technical teams benefit when internal ops can automate handoffs. Provide a few endpoints and event hooks with copy-paste examples.

# Create a dependency from a release checklist

curl -X POST /api/dependencies \

-H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" \

-d '{"title":"API contract from Payments","trackerUrl":"https://jira/.../PAY-77"}'

Webhooks like dependency.created and dependency.status_changed let teams integrate with internal tools without waiting on your roadmap. For more, link to /docs/integrations.

Dashboards are where a dependency app earns its keep: they turn “I think we’re blocked” into a clear, shared picture of what needs attention before the next check-in.

A single “one size fits all” dashboard usually fails. Instead, design a few views that match how people run meetings:

Build a small set of reports people will actually use in reviews:

Each report should answer: “Who needs to do what next?” Include owner, expected date, and last update.

Make filtering fast and obvious, because most meetings start with “show me just…”

Support filters like team, initiative, status, due date range, risk level, and tags (e.g., “security review,” “data contract,” “release train”). Save common filter sets as named views (e.g., “Release A — next 14 days”).

Not everyone will live in your app all day. Provide:

If you offer a paid tier, keep admin-friendly sharing controls and point to /pricing for details.

You don’t need a complex platform to ship a dependency tracking web app. An MVP can be a simple three-part system: a web UI for humans, an API for rules and integrations, and a database for the source of truth. Optimize for “easy to change” over “perfect.” You’ll learn more from real usage than from months of upfront architecture.

A pragmatic starting point looks like this:

If you expect Slack/Jira integration soon, keep integrations as separate modules/jobs that talk to the same API, rather than letting external tools write directly to the database.

If you want to get to a working product quickly without standing up everything from scratch, a vibe-coding workflow can help: for example, Koder.ai can generate a React web UI and a Go + PostgreSQL backend from a chat-based spec, then let you iterate using planning mode, snapshots, and rollback. You still own the architecture decisions, but you can shorten the path from “requirements” to “usable pilot,” and export the source code when you’re ready to take it fully in-house.

Most screens are list views: open dependencies, blockers by team, changes this week. Design for that:

Dependency data can include sensitive delivery details. Use least-privilege access (team-level visibility where appropriate) and keep audit logs for edits—who changed what, and when. That audit trail reduces debate in status reviews and makes the tool feel reliable.

Rolling out a dependency tracking web app is less about features and more about changing habits. Treat the rollout as a product launch: start small, prove value, then scale with a clear operating rhythm.

Pick 2–4 teams working on one shared initiative (for example, a release train or a single customer program). Define success criteria you can measure in a few weeks:

Keep the pilot configuration minimal: only the fields and views required to answer, “What’s blocked, by whom, and by when?”

Most teams already track project dependencies in spreadsheets. Import them, but do it intentionally:

Run a short “data QA” pass with pilot users to confirm definitions and fix ambiguous entries.

Adoption sticks when the app supports an existing cadence. Provide:

If you’re building quickly (for instance, iterating the pilot in Koder.ai), use environments/snapshots to test changes to required fields, states, and dashboards with the pilot teams—then roll forward (or roll back) without disrupting everyone.

Track where people get stuck: confusing fields, missing statuses, or views that don’t answer review questions. Review feedback weekly during the pilot, then adjust fields and default views before inviting more teams. A simple “Report an issue” link to /support helps keep the loop tight.

Once your dependency tracking app is live, the biggest risks aren’t technical—they’re behavioral. Most teams don’t abandon tools because they “don’t work,” but because updating them feels optional, confusing, or noisy.

Too many fields. If creating a dependency feels like filling out a form, people will delay it or skip it. Start with a minimal set of required fields: title, requesting team, owning team, “next action,” due date, and status.

Unclear ownership. If it’s not obvious who must act next, dependencies become status threads. Make “owner” and “next action owner” explicit, and display them prominently.

No update habits. Even a great UI fails if items go stale. Add gentle nudges: highlight stale items in lists, send reminders only when a due date is near or the last update is old, and make updates easy (one-click status change plus a short note).

Notification overload. If every comment pings everyone, users will mute the system. Default to “watchers” who opt in, and send summaries (daily/weekly) for low urgency.

Treat “next action” as a first-class field: every open dependency should always have a clear next step and a single accountable person. If it’s missing, the item shouldn’t look “complete” in key views.

Also define what “done” means (e.g., resolved, no longer needed, or moved to another tracker) and require a short closure reason to avoid zombie items.

Decide who owns your tags, team list, and categories. Typically it’s a program manager or ops role with lightweight change control. Set a simple retirement policy: archive old initiatives automatically after X days closed, and review unused tags quarterly.

After adoption stabilizes, consider upgrades that add value without adding friction:

If you need a structured way to prioritize enhancements, tie each idea to a review ritual (weekly status meeting, release planning, incident retros) so improvements are driven by real usage—not guesses.

Start with a one-sentence definition everyone can repeat, then list what qualifies (work item, deliverable, decision, environment/access).

Also write down what does not count (nice-to-haves, general risks, internal tasks that don’t block another team). This keeps the tool from becoming a vague “concern tracker.”

At minimum, design for:

If you build for only one group, the others won’t update it—and the system will go stale.

Use a small, consistent lifecycle such as:

Then define rules for state changes (e.g., “Accepted requires an owner team and a target date,” “Ready requires evidence”). Consistency matters more than complexity.

Require only what you need to coordinate:

If you allow missing owner or due date, you’ll collect items that can’t be acted on.

Make “done” provable. Require:

This prevents early “green status” updates just to reduce noise.

Define four everyday roles plus admin:

Keep “one dependency, one owner” to avoid ambiguity; use collaborators for helpers, not accountability.

Start with views that answer daily questions:

Optimize for fast updates: templates, inline editing, keyboard-friendly controls, and a prominent “Last updated.”

Alert only on decision points and risk signals:

Use watchers instead of broadcasting, support digest mode, and deduplicate notifications (one summary per dependency per time window).

Integrate to remove duplicate entry, not to create a second source of truth:

dependency.created, dependency.status_changed)Keep chat (Slack/Teams) as a delivery channel that deep-links back to the record, not the system of record.

Run a focused pilot before scaling:

Treat “no owner or due date” as incomplete, and iterate based on where users get stuck.