Nov 06, 2025·8 min

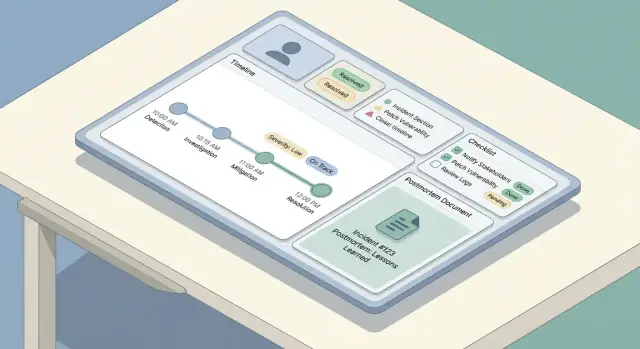

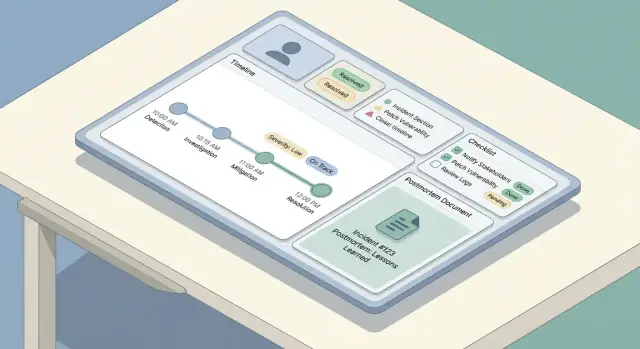

How to Build a Web App for Incident Tracking & Postmortems

A practical blueprint to design, build, and launch a web app for incident tracking and postmortems, from workflows to data modeling and UX.

A practical blueprint to design, build, and launch a web app for incident tracking and postmortems, from workflows to data modeling and UX.

Before you sketch screens or choose a database, align on what your team means by an incident tracking web app—and what “postmortem management” should accomplish. Teams often use the same words differently: for one group, an incident is any customer-reported issue; for another, it’s only a Sev-1 outage with an on-call escalation.

Write a short definition that answers:

This definition drives your incident response workflow and prevents the app from becoming either too strict (nobody uses it) or too loose (data is inconsistent).

Decide what a postmortem is in your organization: a lightweight summary for every incident, or a full RCA only for high-severity events. Make it explicit whether the goal is learning, compliance, reducing repeat incidents, or all three.

A helpful rule: if you expect a postmortem to produce change, then your tool must support action items tracking, not just document storage.

Most teams build this kind of app to fix a small set of recurring pain points:

Keep this list tight. Every feature you add should map to at least one of these problems.

Pick a few metrics you can measure automatically from your app’s data model:

These become your operational metrics and your “definition of done” for the first release.

The same app serves different roles in on-call operations:

If you design for all of them at once, you’ll build a cluttered UI. Instead, pick a primary user for v1—and ensure everyone else can still get what they need via tailored views, dashboards, and permissions later.

A clear workflow prevents two common failure modes: incidents that stall because nobody knows “what’s next,” and incidents that look “done” but never produce learning. Start by mapping your lifecycle end-to-end and then attach roles and permissions to each step.

Most teams follow a simple arc: detect → triage → mitigate → resolve → learn. Your app should reflect this with a small set of predictable steps, not an endless menu of options.

Define what “done” means for each stage. For example, mitigation might mean customer impact is stopped, even if the root cause is still unknown.

Keep roles explicit so people can act without waiting for meetings:

Your UI should make the “current owner” visible, and your workflow should support delegation (reassigning, adding responders, rotating commander).

Choose required states and allowed transitions, such as Investigating → Mitigated → Resolved. Add guardrails:

Separate internal updates (fast, tactical, can be messy) from stakeholder-facing updates (clear, time-stamped, curated). Build two update streams with different templates, visibility, and approval rules—often the commander is the only publisher for stakeholder updates.

A good incident tool feels “simple” in the UI because the data model underneath is consistent. Before building screens, decide what objects exist, how they relate, and what must be historically accurate.

Start with a small set of first-class objects:

Most relationships are one-to-many:

Use stable identifiers (UUIDs) for incidents and events. Humans still need a friendly key like INC-2025-0042, which you can generate from a sequence.

Model these early so you can filter, search, and report:

Incident data is sensitive and often reviewed later. Treat edits as data—not overwrites:

This structure makes later features—search, metrics, and permissions—much easier to implement without rework.

When something breaks, the app’s job is to reduce typing and increase clarity. This section covers the “write path”: how people create an incident, keep it updated, and reconstruct what happened later.

Keep the intake form short enough to finish while you’re troubleshooting. A good default set of required fields is:

Everything else should be optional at creation time (impact, customer ticket links, suspected cause). Use smart defaults: set start time to “now”, preselect the user’s on-call team, and offer a one-tap “Create & open incident room” action.

Your update UI should be optimized for repeated, small edits. Provide a compact update panel with:

Make updates append-friendly: each update becomes a timestamped entry, not an overwrite of previous text.

Build a timeline that mixes:

This creates a reliable narrative without forcing people to remember to log every click.

During an outage, many updates happen from a phone. Prioritize a fast, low-friction screen: large touch targets, a single scrolling page, offline-friendly drafts, and one-tap actions like “Post update” and “Copy incident link”.

Severity is the “speed dial” of incident response: it tells people how urgently to act, how widely to communicate, and what trade-offs are acceptable.

Avoid vague labels like “high/medium/low.” Make each severity level map to clear operational expectations—especially response time and communication cadence.

For example:

Make these rules visible in the UI wherever severity is chosen, so responders don’t need to hunt through documentation.

Checklists reduce cognitive load when people are stressed. Keep them short, actionable, and tied to roles.

A useful pattern is a few sections:

Make checklist items timestamped and attributable, so they become part of the incident record.

Incidents rarely live in one tool. Your app should let responders attach links to:

Prefer “typed” links (e.g., Runbook, Ticket) so they can be filtered later.

If your org tracks reliability targets, add lightweight fields such as SLO affected (yes/no), estimated error budget burn, and customer SLA risk. Keep them optional—but easy to fill during or right after the incident, when details are freshest.

A good postmortem is easy to start, hard to forget, and consistent across teams. The simplest way to get there is to provide a default template (with minimal required fields) and auto-fill it from the incident record so people spend time thinking—not retyping.

Your built-in template should balance structure with flexibility:

Make “Root cause” optional early on if you want faster publishing, but require it before final approval.

The postmortem shouldn’t be a separate document floating around. When a postmortem is created, automatically attach:

Use these to pre-fill the postmortem sections. For example, the “Impact” block can start with the incident’s start/end times and current severity, while “What we did” can pull from timeline entries.

Add a lightweight workflow so postmortems don’t stall:

At each step, capture decision notes: what changed, why it changed, and who approved it. This avoids “silent edits” and makes future audits or learning reviews much easier.

If you want to keep the UI simple, treat reviews like comments with explicit outcomes (Approve / Request changes) and store the final approval as an immutable record.

For teams that need it, link “Published” to your status updates workflow (see /blog/integrations-status-updates) without copying content by hand.

Postmortems only reduce future incidents if the follow-up work actually happens. Treat action items as first-class objects in your app—not a paragraph at the bottom of a document.

Each action item should have consistent fields so it can be tracked and measured:

Add small but useful metadata: tags (e.g., “monitoring”, “docs”), component/service, and “created from” (incident ID and postmortem ID).

Don’t trap action items inside a single postmortem page. Provide:

This turns follow-ups into an operational queue rather than scattered notes.

Some tasks repeat (quarterly game days, runbook reviews). Support a recurring template that generates new items on a schedule, while keeping each occurrence independently trackable.

If teams already use another tracker, allow an action item to include an external reference link and external ID, while keeping your app as the source for incident linkage and verification.

Build lightweight nudges: notify owners as due dates approach, flag overdue items to a team lead, and surface chronic overdue patterns in reports. Keep rules configurable so teams can match their on-call operations and workload reality.

Incidents and postmortems often contain sensitive details—customer identifiers, internal IPs, security findings, or vendor issues. Clear access rules keep the tool useful for collaboration without turning it into a data leak.

Start with a small, understandable set of roles:

If you have multiple teams, consider scoping roles by service/team (e.g., “Payments Editors”) rather than granting broad global access.

Classify content early, before people build habits:

A practical pattern is to mark sections as Internal or Shareable and enforce it in exports and status pages. Security incidents may require a separate incident type with stricter defaults.

For every change to incidents and postmortems, record: who changed it, what changed, and when. Include edits to severity, timestamps, impact, and “final” approvals. Make audit logs searchable and non-editable.

Support strong auth out of the box: email + MFA or magic link, and add SSO (SAML/OIDC) if your users expect it. Use short-lived sessions, secure cookies, CSRF protection, and automatic session revocation on role changes. For more rollout considerations, see /blog/testing-rollout-continuous-improvement.

When an incident is active, people scan—not read. Your UX should make the current state obvious in seconds, while still letting responders drill into details without getting lost.

Start with three screens that cover most workflows:

A simple rule: the incident detail page should answer “What’s happening right now?” at the top, and “How did we get here?” below.

Incidents pile up quickly, so make discovery fast and forgiving:

Offer saved views like My open incidents or Sev-1 this week so on-call engineers don’t rebuild filters every shift.

Use consistent, color-safe badges across the app (and avoid subtle shades that fail under stress). Keep the same status vocabulary everywhere: list, detail header, and timeline events.

At a glance, responders should see:

Prioritize scannability:

Design for the worst moment: if someone is sleep-deprived and paging through their phone, the UI should still guide them to the right action fast.

Integrations are what turn an incident tracker from “a place to write notes” into the system your team actually runs incidents in. Start by listing the systems you must connect: monitoring/observability (PagerDuty/Opsgenie, Datadog, CloudWatch), chat (Slack/Teams), email, ticketing (Jira/ServiceNow), and a status page.

Most teams end up with a mix:

Alerts are noisy, retried, and often arrive out of order. Define a stable idempotency key per provider event (for example: provider + alert_id + occurrence_id), and store it with a unique constraint. For deduplication, decide rules like “same service + same signature within 15 minutes” should append to an existing incident rather than create a new one.

Be explicit about what your app owns versus what stays in the source tool:

When an integration fails, degrade gracefully: queue retries, surface a warning on the incident (“Slack posting delayed”), and always allow operators to continue manually.

Treat status updates as a first-class output: a structured “Update” action in your UI should be able to publish to chat, append to the incident timeline, and optionally sync to the status page—without asking the responder to write the same message three times.

Your incident tool is a “during-an-outage” system, so favor simplicity and reliability over novelty. The best stack is usually the one your team can build, debug, and operate at 2 a.m. with confidence.

Start with what your engineers already ship in production. A mainstream web framework (Rails, Django, Laravel, Spring, Express/Nest, ASP.NET) is typically a safer bet than a brand-new framework that only one person understands.

For data storage, a relational database (PostgreSQL/MySQL) fits incident records well: incidents, updates, participants, action items, and postmortems all benefit from transactions and clear relationships. Add Redis only if you truly need caching, queues, or ephemeral locks.

Hosting can be as simple as a managed platform (Render/Fly/Heroku-like) or your existing cloud (AWS/GCP/Azure). Prefer managed databases and managed backups if possible.

Active incidents feel better with real-time updates, but you don’t always need websockets on day one.

A practical approach: design the API/events so you can start with polling and upgrade to websockets later without rewriting the UI.

If this app fails during an incident, it becomes part of the incident. Add:

Treat this like a production system:

If you want to validate the workflow and screens before investing in a full build, a vibe-coding approach can work well: use a tool like Koder.ai to generate a working prototype from a detailed chat specification, then iterate with responders during tabletop exercises. Because Koder.ai can produce real React frontends with a Go + PostgreSQL backend (and supports source code export), you can treat early versions as “throwaway prototypes” or as a starting point your team can harden—without losing the learnings you gathered from real incident simulations.

Shipping an incident tracking app without rehearsal is a gamble. The best teams treat the tool like any other operational system: test the critical paths, run realistic drills, roll out gradually, and keep tuning based on real usage.

Focus first on the flows people will rely on during high stress:

Add regression tests that validate what must not break: timestamps, time zones, and event ordering. Incidents are narratives—if the timeline is wrong, trust is gone.

Permission bugs are operational and security risks. Write tests that prove:

Also test “near misses,” like a user losing access mid-incident or a team reorg changing group membership.

Before broad rollout, run tabletop simulations using your app as the source of truth. Pick scenarios your org recognizes (e.g., partial outage, data delay, third-party failure). Watch for friction: confusing fields, missing context, too many clicks, unclear ownership.

Capture feedback immediately and turn it into small, fast improvements.

Start with one pilot team and a few pre-built templates (incident types, checklists, postmortem formats). Provide short training and a one-page “how we run incidents” guide linked from the app (e.g., /docs/incident-process).

Track adoption metrics and iterate on friction points: time-to-create, % incidents with updates, postmortem completion rate, and action-item closure time. Treat these as product metrics—not compliance metrics—and keep improving every release.

Start by writing a concrete definition your org agrees on:

That definition should map directly to your workflow states and required fields so data stays consistent without becoming burdensome.

Treat postmortems as a workflow, not a document:

If you expect change, you need action-item tracking and reminders—not just storage.

A practical v1 set is:

Skip advanced automation until these flows work smoothly under stress.

Use a small number of predictable stages aligned to how teams actually work:

Define “done” for each stage, then add guardrails:

This prevents stalled incidents and improves the quality of later analysis.

Model a few clear roles and tie them to permissions:

Make the current owner/commander unmistakable in the UI and allow delegation (reassign, rotate commander).

Keep the data model small but structured:

Use stable identifiers (UUIDs) plus a human-friendly key (e.g., INC-2025-0042). Treat edits as history with created_at/created_by and an audit log for changes.

Separate streams and apply different rules:

Implement different templates/visibility, and store both in the incident record so you can reconstruct decisions later without leaking sensitive details.

Define severity levels with explicit expectations (response urgency and comms cadence). For example:

Surface the rules in the UI wherever severity is chosen so responders don’t need external docs during an outage.

Treat action items as structured records, not free text:

Then provide global views (overdue, due soon, by owner/service) and lightweight reminders/escalation so follow-ups don’t vanish after the review meeting.

Use provider-specific idempotency keys and dedup rules:

provider + alert_id + occurrence_idAlways allow manual linking as a fallback when APIs or integrations fail.