Nov 30, 2025·8 min

How to Create a Web App for Service Outage Communications

Learn how to plan, build, and launch a web app that manages outage updates across channels, with templates, approvals, audit logs, and clear incident timelines.

Learn how to plan, build, and launch a web app that manages outage updates across channels, with templates, approvals, audit logs, and clear incident timelines.

A service outage communications web app exists to do one job extremely well: help your team publish clear, consistent updates quickly—without guessing what was said where, or who approved it.

When incidents happen, the technical fix is only half the work. The other half is communication: customers want to know what’s impacted, what you’re doing, and when they should check back. Internal teams need a shared source of truth so support, success, and leadership aren’t improvising messages.

Your app should reduce “time to first update” and keep every subsequent update aligned across channels. That means:

Speed matters, but accuracy matters more. The app should encourage writing that is specific (“API requests are failing for EU customers”) rather than vague (“We are experiencing issues”).

You’re not writing for one reader. Your app should support multiple audiences with different needs:

A practical approach is to treat your public status page as the “official story,” while allowing internal notes and partner-specific updates that don’t need to be public.

Most teams start with chat messages, ad-hoc docs, and manual emails. Common failures include scattered updates, inconsistent wording, and missed approvals. Your app should prevent:

By the end of this guide, you’ll have a clear plan for an MVP that can:

Then you’ll extend it into a v1 with stronger permissions, audience targeting, integrations, and reporting—so incident communication becomes a process, not a scramble.

Before you design screens or pick a tech stack, define who the app is for, how an incident moves through the system, and where messages will be published. Clear requirements here prevent two common failure modes: slow approvals and inconsistent updates.

Most teams need a small set of roles with predictable permissions:

A practical requirement: make it obvious what’s draft vs approved vs published, and by whom.

Map the end-to-end lifecycle as explicit states:

detect → confirm → publish → update → resolve → review

Each step should have required fields (e.g., impacted services, customer-facing summary) and a clear “next action” so people don’t improvise under pressure.

List every destination your team uses and define the minimum capabilities for each:

Decide upfront whether the status page is the “source of truth” and other channels mirror it, or whether some channels can carry extra context.

Set internal targets like “first public acknowledgement within X minutes after confirmation,” plus lightweight checks: required template, plain-language summary, and an approval rule for high-severity incidents. These are process goals—not guarantees—to keep messaging consistent and timely.

A clear data model keeps outage communications consistent: it prevents “two versions of the truth,” makes timelines easy to follow, and gives you reliable reporting later.

At minimum, model these entities explicitly:

Use a small, predictable set of incident states: investigating → identified → monitoring → resolved.

Treat Updates as an append-only timeline: each update should store the timestamp, author, state at the time, visible audiences, and the rendered content sent to each channel.

Add “milestone” flags on updates (e.g., start detected, mitigation applied, full recovery) so the timeline is readable and report-friendly.

Model many-to-many links:

This structure supports accurate status pages, consistent subscriber notifications, and a dependable communication audit log.

A good outage communications app should feel calm even when the incident isn’t. The key is to separate public consumption from internal operations, and to make the “next right action” obvious on every screen.

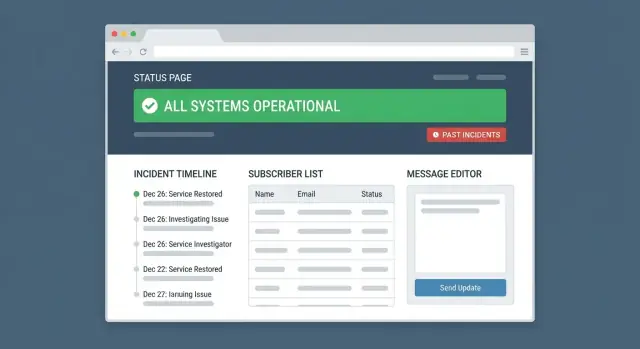

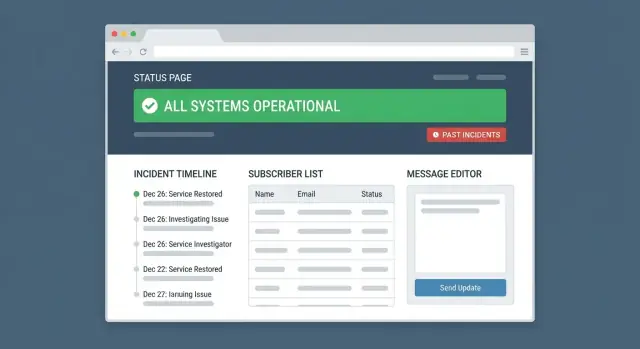

The public page should answer three questions within seconds: “Is it down?” “What’s affected?” “When will I know more?”

Show a clear overall state (Operational / Degraded / Partial Outage / Major Outage), followed by any active incidents with the most recent update at the top. Keep update text readable, with timestamps and a short incident title.

Add a compact history view so customers can confirm whether issues are recurring without forcing them to search. A simple filter by component (e.g., API, Dashboard, Payments) helps customers self-diagnose.

This is the “control room.” It should prioritize speed and consistency:

Make the primary action button contextual: “Post update” during an active incident, “Resolve incident” when stable, “Start new incident” when none are open. Reduce typing by pre-filling common fields and remembering recent selections.

Subscriptions should be simple and privacy-respecting. Let users:

Confirm what they’ll receive (“Only Major Outages for API”) to prevent surprise notifications.

Admins need dedicated screens for setup so responders can focus on writing updates:

A small UX detail that pays off: include a read-only preview of how an update will look on each channel, so teams catch formatting issues before publishing.

During an outage, the hardest part isn’t writing perfect prose—it’s publishing accurate updates quickly, without creating confusion or skipping internal checks. Your app’s publishing workflow should make “send the next update” feel as fast as sending a chat message, while still supporting governance when it matters.

Start with a few opinionated templates aligned to common stages: Investigating, Identified, Monitoring, and Resolved. Each template should pre-fill a clear structure: what users are experiencing, what you know, what you’re doing, and when you’ll update next.

A good template system also supports:

Not every update needs approval. Design approvals as a per-incident (or per-update) toggle:

Keep the flow lightweight: a draft editor, a single “Request review” action, and clear reviewer feedback. Once approved, publishing should be one click—no copying text across tools.

Scheduling is essential for planned maintenance and coordinated announcements. Support:

To reduce mistakes further, add a final preview step that shows exactly what will be published to each channel before it goes out.

When an incident is active, the biggest risk isn’t silence—it’s mixed messages. A customer who sees “degraded” on your status page but “resolved” on social will lose confidence fast. Your web app should treat every update as one source of truth, then publish it consistently everywhere.

Start with a single canonical message: what’s happening, who’s affected, and what customers should do. From that shared copy, generate channel-specific variants (Status Page, email, SMS, Slack, social) while keeping the meaning aligned.

A practical pattern is “master content + per-channel formatting”:

Multi-channel publishing needs guardrails, not just buttons:

Incidents get chaotic. Build protections so you don’t send the same update twice or edit history accidentally:

Record delivery outcomes per channel—sent time, failures, provider response, and audience size—so you can answer, “Did customers actually receive this?” later and improve your process.

A status page is useful even without subscribers, but subscriptions are what turn it into a real communication system. The goal is simple: let people choose what they want to hear about, deliver it at a reasonable cadence, and make opting out effortless.

Start with a clear opt-in flow that sets expectations:

Keep the copy specific (“Get updates for Payments and API incidents”) rather than generic (“Receive notifications”).

Not every incident affects everyone. Build targeting rules that match how customers understand your product:

When publishing an update, the sender should see a preview like: “This will notify 1,240 subscribers: API + EU + Enterprise.” That one line prevents most accidental over-notifications.

Subscribers leave when messages feel noisy. Two safeguards help:

Unsubscribe should be one click, work immediately, and be channel-specific:

Record unsubscribes and preference changes as part of your communication audit log so support can answer, “Why didn’t I get notified?” without guessing.

Outage communication is high-impact: a single mistaken edit can create confusion for customers, support teams, and executives. Your MVP should treat security and governance as core product features, not add-ons.

Pick Single Sign-On (SSO) (OIDC/SAML) so only employees with company-managed accounts can access the tool. This reduces password resets, improves offboarding (disable the corporate account and access disappears), and makes it easier to enforce policies like MFA.

Keep a small “break-glass” path for emergencies (e.g., one admin account stored in a password manager), but use it rarely and log it heavily.

Define roles around the outage workflow:

Make permissions specific. For example, allow Editors to update an incident timeline but prevent them from changing “affected services” unless they’re on the owning team. If you have multiple products, add service-level permissions so teams can only edit what they own.

An audit log should record every meaningful action: edits, publishes/unpublishes, schedule changes, template changes, and permission updates.

Capture: who did it, when, what changed (before/after), incident/service affected, and metadata like IP address and user agent. Make the log searchable and exportable, and prevent users from deleting entries.

Set clear retention defaults (commonly 12–36 months) and allow longer retention for regulated customers.

Provide exports in CSV/JSON for incident records and audit logs, with a documented process for compliance requests. If data must be deleted, do it predictably (e.g., automated policy) and log the deletion event itself.

Integrations are what turn your outage communications app from a manual “type-and-publish” tool into a reliable part of incident response. For an MVP, focus on a few high-leverage connections and design them so they fail safely.

Start with four categories:

Inbound webhooks should allow trusted systems to:

Make idempotency a first-class feature (e.g., Idempotency-Key header) so repeated alerts don’t create duplicate incidents.

Outbound webhooks trigger when an update is published, edited, or resolved. Typical uses:

Treat delivery failures as normal:

This approach keeps messaging consistent even when downstream systems are unreliable.

You can ship a reliable outage communications app without over-engineering. The trick is to make a few structural decisions that keep you safe today and flexible later.

Treat the public status experience and the internal incident console as different products.

The public side should be fast, cache-friendly, and resilient under heavy traffic (when everyone refreshes during an outage). Keep it read-only, with minimal dependencies, and avoid exposing admin routes or APIs directly.

The admin side can be behind authentication, with richer interactions and integrations. If you deploy both from the same codebase, still separate routes, permissions, and infrastructure concerns (e.g., stricter rate limits and additional logging for admin).

Two common MVP options work well:

If you’re unsure, SSR often wins early because it reduces complexity and operational overhead.

If you want to move faster from “requirements” to a working console and status page, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you prototype the full workflow in days: a React-based admin UI, a Go API, and a PostgreSQL data model for incidents/updates/subscribers. Planning mode is especially useful for mapping roles, states, and channel rules before you generate screens, and snapshots/rollback can reduce risk when you iterate on publishing logic.

A relational database (Postgres/MySQL) fits incident workflows nicely: services, incidents, updates, subscribers, and audit logs all have clear relationships.

Design for append-only updates (don’t overwrite history). That makes incident timelines accurate and makes reporting easier later.

Don’t send email/SMS/push inside web requests. Use background jobs for:

This keeps the app responsive during peak incident activity and prevents “double sends” when someone refreshes the admin page.

Once the incident is resolved, your communications app should switch from “broadcast mode” to “learning and evidence mode.” Good reporting helps you prove you communicated responsibly, answer customer questions quickly, and improve future response.

Focus on a small set of metrics that reflect communication quality, not just system uptime:

Pair these with simple charts and a per-incident “communication scorecard” so teams can spot patterns without digging through logs.

An incident history page should work for two audiences: external users looking for context and internal teams handling tickets.

Make it searchable and filterable by:

Each incident page should show a clean timeline of updates, including who published each update and which channels it went to (internal view). This becomes your default reference link for support responses.

Not every organization wants to publish a full postmortem, but a short post-incident note can reduce repeat questions.

Consider a structured template with:

Support both private and public visibility, with approvals if you require them.

Make it easy to export an incident timeline (including timestamps and update text) to common formats such as CSV or PDF.

Exports should include:

This is useful for customer success, compliance reviews, and attaching context to support tickets without copying and pasting from multiple tools.

If you’re building this on Koder.ai, source code export can be handy once the workflow stabilizes—your team can take the generated React/Go/PostgreSQL project, run a deeper security review, and deploy it into your standard environment.

Before you put an outage communications app in front of customers, test it like it’s production—because during an incident, it effectively is.

Run a short tabletop exercise with real roles (on-call, comms, approver) and verify:

Also test time zones, mobile layout for the status page, and high-traffic caching behavior (a status page often gets more traffic than your marketing site during an outage).

Treat the app as a critical system:

Good updates are short and consistent:

Launch in stages: enable internal-only incidents first, then turn on the public status page, and finally enable subscriptions once you’re confident in unsubscribe flows and rate limits.

If you need a low-friction way to validate the whole workflow end-to-end, you can build and host an MVP on Koder.ai (Free/Pro/Business/Enterprise tiers) and iterate quickly with planning mode, then use snapshots/rollback as you harden permissions and delivery reliability.

An outage communications web app is a dedicated tool for creating, approving, and publishing incident updates as a single source of truth across channels (status page, email/SMS, chat, social, in-app banners). It reduces “time to first update,” prevents channel drift, and preserves a reliable timeline of what was communicated and when.

Treat the public status page as the canonical story, then mirror that update into other channels.

Practical safeguards:

Common roles include:

A simple, explicit lifecycle prevents improvisation:

Enforce required fields at each step (for example: impacted services, customer-facing summary, and “next update time”) so responders can’t publish vague or incomplete updates under pressure.

Start with these entities:

Use a small, predictable set: Investigating → Identified → Monitoring → Resolved.

Implementation tips:

Build a few templates mapped to the lifecycle (Investigating/Identified/Monitoring/Resolved) with fields like:

Add guardrails such as SMS character limits, required fields, and placeholders (service/region/incident ID).

Make approvals configurable by severity or incident type:

Keep it lightweight: one Request review action, visible reviewer feedback, and one-click publish after approval—no copying text between tools.

Minimum, privacy-respecting subscription features:

To reduce fatigue:

Prioritize:

This protects against accidental publishes and makes post-incident reviews defensible.

Make it obvious what’s draft vs approved vs published, and by whom.

This model supports clear timelines, targeted notifications, and durable reporting.