Oct 30, 2025·8 min

How to Create a Web App to Track Experiment Results by Product

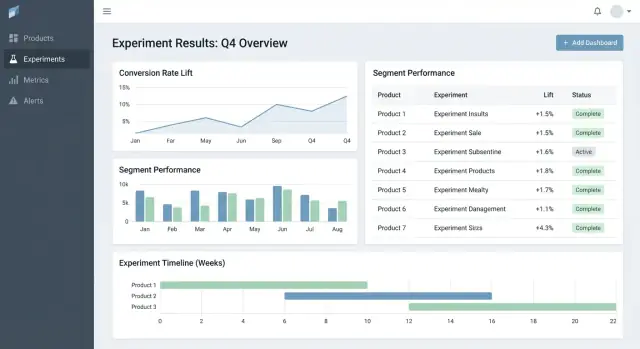

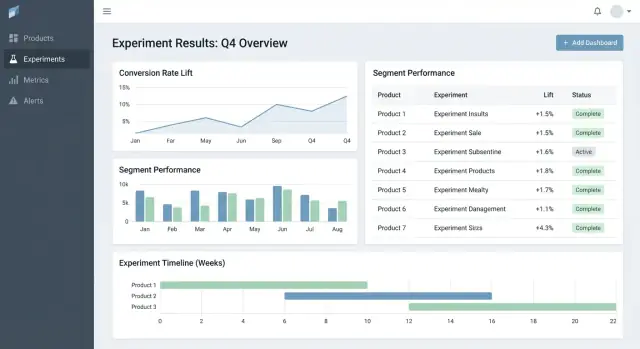

Learn how to build a web app to track experiments across products: data model, metrics, permissions, integrations, dashboards, and reliable reporting.

Learn how to build a web app to track experiments across products: data model, metrics, permissions, integrations, dashboards, and reliable reporting.

Most teams don’t fail at experimentation because they lack ideas—they fail because results are scattered. One product has charts in an analytics tool, another has a spreadsheet, a third has a slide deck with screenshots. A few months later, nobody can answer simple questions like “Did we already test this?” or “Which version won, using which metric definition?”

An experiment tracking web app should centralize what was tested, why, how it was measured, and what happened—across multiple products and teams. Without this, teams waste time rebuilding reports, arguing about numbers, and re-running old tests because learnings aren’t searchable.

This isn’t just an analyst tool.

A good tracker creates business value by enabling:

Be explicit: this app is primarily for tracking and reporting experiment results—not for running experiments end-to-end. It can link out to existing tools (feature flagging, analytics, data warehouse) while owning the structured record of the experiment and its final, agreed interpretation.

A minimum viable experiment tracker should answer two questions without hunting through docs or spreadsheets: what are we testing and what did we learn. Start with a small set of entities and fields that work across products, then expand only when teams feel real pain.

Keep the data model simple enough that every team uses it the same way:

Support the most common patterns from day one:

Even if rollouts don’t use formal statistics at first, tracking them alongside experiments helps teams avoid repeating the same “tests” with no record.

At creation time, require only what’s needed to run and interpret the test later:

Make results comparable by forcing structure:

If you build just this, teams can reliably find experiments, understand setup, and record outcomes—even before you add advanced analytics or automation.

A cross-product experiment tracker succeeds or fails on its data model. If IDs collide, metrics drift, or segments are inconsistent, your dashboard can look “right” while telling the wrong story.

Start with a clear identifier strategy:

checkout_free_shipping_banner) plus an immutable experiment_idcontrol, treatment_aThis lets you compare results across products without guessing whether “Web Checkout” and “Checkout Web” are the same thing.

Keep the core entities small and explicit:

Even if computation happens elsewhere, storing the outputs (results) enables fast dashboards and a reliable history.

Metrics and experiments aren’t static. Model:

This prevents last month’s experiments from changing when someone updates KPI logic.

Plan for consistent segments across products: country, device, plan tier, new vs returning.

Finally, add an audit trail capturing who changed what and when (status changes, traffic splits, metric definition updates). It’s essential for trust, reviews, and governance.

If your experiment tracker gets metric math wrong (or inconsistent across products), the “result” is just an opinion with a chart. The fastest way to prevent this is to treat metrics as shared product assets—not ad‑hoc query snippets.

Create a metric catalog that is the single source of truth for definitions, calculation logic, and ownership. Each metric entry should include:

Keep the catalog close to where people work (e.g., linked from your experiment creation flow) and version it so you can explain historical results.

Decide up front what “unit of analysis” each metric uses: per user, per session, per account, or per order. A conversion rate “per user” can disagree with “per session” even when both are correct.

To reduce confusion, store the aggregation choice with the metric definition, and require it when an experiment is set up. Don’t let each team pick a unit ad hoc.

Many products have conversion windows (e.g., signup today, purchase within 14 days). Define attribution rules consistently:

Make these rules visible in the dashboard so readers know what they’re looking at.

For fast dashboards and auditability, store both:

This enables quick rendering while still letting you recompute when definitions change.

Adopt a naming standard that encodes meaning (e.g., activation_rate_user_7d, revenue_per_account_30d). Require unique IDs, enforce aliases, and flag near-duplicates during metric creation to keep the catalog clean.

Your experiment tracker is only as credible as the data it ingests. The goal is to reliably answer two questions for every product: who was exposed to which variant, and what did they do afterward? Everything else—metrics, statistics, dashboards—depends on that foundation.

Most teams choose one of these patterns:

Whatever you pick, standardize the minimum event set across products: exposure/assignment, key conversion events, and enough context to join them (user ID/device ID, timestamp, experiment ID, variant).

Define a clear mapping from raw events to metrics your tracker reports (e.g., purchase_completed → Revenue, signup_completed → Activation). Maintain this mapping per product, but keep naming consistent across products so your A/B test results dashboard compares like with like.

Validate completeness early:

Build checks that run on every load and fail loudly:

Surface these in the app as warnings attached to an experiment, not hidden in logs.

Pipelines change. When you fix an instrumentation bug or dedupe logic, you’ll need to reprocess historical data to keep metrics and KPIs consistent.

Plan for:

Treat integrations as product features: document supported SDKs, event schemas, and troubleshooting steps. If you have a docs area, link it as a relative path like /docs/integrations.

If people don’t trust the numbers, they won’t use the tracker. The goal isn’t to impress with math—it’s to make decisions repeatable and defensible across products.

Decide upfront whether your app will report frequentist results (p-values, confidence intervals) or Bayesian results (probability of improvement, credible intervals). Both can work, but mixing them across products causes confusion (“Why does this test show 97% chance to win, while that one shows p=0.08?”).

A practical rule: choose the approach your org already understands, then standardize terminology, defaults, and thresholds.

At a minimum, your results view should make these items unambiguous:

Also show the analysis window, units counted (users, sessions, orders), and the metric definition version used. These “details” are the difference between consistent reporting and debate.

If teams test many variants, many metrics, or check results daily, false positives become likely. Your app should encode a policy rather than leaving it to each team:

Add automated flags that appear next to results, not hidden in logs:

Next to the numbers, add a short explanation that a non-technical reader can trust, such as: “The best estimate is +2.1% lift, but the true effect could plausibly be between -0.4% and +4.6%. We don’t have strong enough evidence to call a winner yet.”

Good experiment tooling helps people answer two questions quickly: What should I look at next? and What should we do about it? The UI should minimize hunting for context and make “decision state” explicit.

Start with three pages that cover most usage:

On the list and product pages, make filters fast and sticky: product, owner, date range, status, primary metric, and segment. People should be able to narrow to “Checkout experiments, owned by Maya, running this month, primary metric = conversion, segment = new users” in seconds.

Treat status as a controlled vocabulary, not free text:

Draft → Running → Stopped → Shipped / Rolled back

Show status everywhere (list rows, detail header, and share links) and record who changed it and why. This prevents “quiet launches” and unclear outcomes.

In the experiment detail view, lead with a compact results table per metric:

Keep advanced charts behind a “More details” section so decision-makers aren’t overwhelmed.

Add CSV export for analysts and shareable links for stakeholders, but enforce access: links should respect roles and product permissions. A simple “Copy link” button plus an “Export CSV” action covers most collaboration needs.

If your experiment tracker spans multiple products, access control and auditability are not optional. They’re what makes the tool safe to adopt across teams and credible during reviews.

Start with a simple set of roles and keep them consistent across the app:

Keep RBAC decisions centralized (one policy layer), so the UI and API enforce the same rules.

Many orgs need product-scoped access: Team A can see Product A experiments but not Product B. Model this explicitly (e.g., user ↔ product memberships), and ensure every query is filtered by product.

For sensitive cases (e.g., partner data, regulated segments), add row-level restrictions on top of product scoping. A practical approach is tagging experiments (or result slices) with a sensitivity level and requiring an additional permission to view them.

Log two things separately:

Expose the change history in the UI for transparency, and keep deeper logs available for investigations.

Define retention rules for:

Make retention configurable by product and sensitivity. When data must be removed, keep a minimal tombstone record (ID, deletion time, reason) to preserve reporting integrity without retaining sensitive content.

A tracker becomes truly useful when it covers the full experiment lifecycle, not just the final p-value. Workflow features turn scattered docs, tickets, and charts into a repeatable process that improves quality and makes learnings easy to reuse.

Model experiments as a series of states (Draft, In Review, Approved, Running, Ended, Readout Published, Archived). Each state should have clear “exit criteria” so experiments don’t go live without essentials like a hypothesis, primary metric, and guardrails.

Approvals don’t need to be heavy. A simple reviewer step (e.g., product + data) plus an audit trail of who approved what and when can prevent avoidable mistakes. After completion, require a short post‑mortem before an experiment can be marked “Published” to ensure results and context are captured.

Add templates for:

Templates reduce “blank page” friction and make reviews faster because everyone knows where to look. Keep them editable per product while preserving a common core.

Experiments rarely live alone—people need the surrounding context. Let users attach links to tickets/specs and related writeups (for example: /blog/how-we-define-guardrails, /blog/experiment-analysis-checklist). Store structured “Learning” fields like:

Support notifications when guardrails regress (e.g., error rate, cancellations) or when results change materially after late data or metric recalculation. Make alerts actionable: show the metric, threshold, timeframe, and an owner to acknowledge or escalate.

Provide a library that filters by product, feature area, audience, metric, outcome, and tags (e.g., “pricing,” “onboarding,” “mobile”). Add “similar experiments” suggestions based on shared tags/metrics so teams can avoid rerunning the same test and instead build on prior learnings.

You don’t need a “perfect” stack to build an experiment tracking web app—but you do need clear boundaries: where data lives, where calculations run, and how teams access results consistently.

For many teams, a simple and scalable setup looks like:

This split keeps transactional workflows fast while letting the warehouse handle large-scale computation.

If you want to prototype the workflow UI quickly (experiments list → detail → readout) before committing to a full engineering cycle, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you generate a working React + backend foundation from a chat spec. It’s especially useful for getting the entities, forms, RBAC scaffolding, and audit-friendly CRUD in place, then iterating on the data contracts with your analytics team.

You typically have three options:

Warehouse-first is often simplest if your data team already owns trusted SQL. Backend-heavy can work when you need low-latency updates or custom logic, but it increases application complexity.

Experiment dashboards often repeat the same queries (top-line KPIs, time series, segment cuts). Plan to:

If you support many products or business units, decide early:

A common compromise is shared infrastructure with a strong tenant_id model and enforced row-level access.

Keep the API surface small and explicit. Most systems need endpoints for experiments, metrics, results, segments, and permissions (plus audit-friendly reads). This makes it easier to add new products without rewriting the plumbing.

An experiment tracker is only useful if people trust it. That trust comes from disciplined testing, clear monitoring, and predictable operations—especially when multiple products and pipelines feed the same dashboards.

Start with structured logging for every critical step: event ingestion, assignment, metric rollups, and result computation. Include identifiers like product, experiment_id, metric_id, and pipeline run_id so support can trace a single result back to its inputs.

Add system metrics (API latency, job runtimes, queue depth) and data metrics (events processed, % late events, % dropped by validation). Complement this with tracing across services so you can answer, “Why is this experiment missing yesterday’s data?”

Data freshness checks are the fastest way to prevent silent failures. If an SLA is “daily by 9am,” monitor freshness per product and per source, and alert when:

Create tests at three levels:

Keep a small “golden dataset” with known outputs so you can catch regressions before shipping.

Treat migrations as part of operations: version your metric definitions and result computation logic, and avoid rewriting historical experiments unless explicitly requested. When changes are required, provide a controlled backfill path and document what changed in an audit trail.

Provide an admin view to re-run a pipeline for a specific experiment/date range, inspect validation errors, and mark incidents with status updates. Link incident notes directly from affected experiments so users understand delays and don’t make decisions on incomplete data.

Rolling out an experiment tracking web app across products is less about “launch day” and more about steadily reducing ambiguity: what’s tracked, who owns it, and whether the numbers match reality.

Start with one product and a small, high-confidence metric set (for example: conversion, activation, revenue). The goal is to validate your end-to-end workflow—creating an experiment, capturing exposure and outcomes, calculating results, and recording the decision—before you scale complexity.

Once the first product is stable, expand product-by-product with a predictable onboarding cadence. Each new product should feel like a repeatable setup, not a custom project.

If your organization tends to get stuck in long “platform build” cycles, consider a two-track approach: build the durable data contracts (events, IDs, metric definitions) in parallel with a thin application layer. Teams sometimes use Koder.ai to stand up that thin layer quickly—forms, dashboards, permissions, and export—then harden it as adoption grows (including source code export and iterative rollbacks via snapshots when requirements change).

Use a lightweight checklist to onboard products and event schemas consistently:

Where it helps adoption, link “next steps” from experiment results to relevant product areas (for example, pricing-related experiments can link to /pricing). Keep links informative and neutral—no implied outcomes.

Measure whether the tool is becoming the default place for decisions:

In practice, most rollouts stumble on a few repeat offenders:

Start by centralizing the final, agreed record of each experiment:

You can link out to feature-flag tools and analytics systems, but the tracker should own the structured history so results stay searchable and comparable over time.

No—keep the scope focused on tracking and reporting results.

A practical MVP:

This avoids rebuilding your entire experimentation platform while still fixing “scattered results.”

A minimum model that works across teams is:

Use stable IDs and treat display names as editable labels:

product_id: never changes, even if the product name doesexperiment_id: immutable internal IDexperiment_key: readable slug (can be enforced unique per product)Make “success criteria” explicit at setup time:

This structure reduces debates later because readers can see what “winning” meant before the test ran.

Create a canonical metric catalog with:

When the logic changes, publish a new metric version instead of editing history—then store which version each experiment used.

At minimum, you need reliable joins between exposure and outcomes:

Then automate checks like:

Pick one “dialect” and standardize UI terms and thresholds:

Whichever you choose, always show:

Treat access control as foundational, not a later add-on:

Also keep two audit trails:

Roll out in a repeatable sequence:

Avoid common pitfalls:

product_id)experiment_id + human-friendly experiment_key)control, treatment_a, etc.)Add Segment and Time window early if you expect consistent slicing (e.g., new vs returning, 7-day vs 30-day).

variant_key: stable strings like control, treatment_aThis prevents collisions and makes cross-product reporting reliable when naming conventions drift.

Surface these as warnings on the experiment page so they’re hard to ignore.

Consistency matters more than sophistication for org-wide trust.

This is what makes the tracker safe to adopt across products and teams.