May 28, 2025·8 min

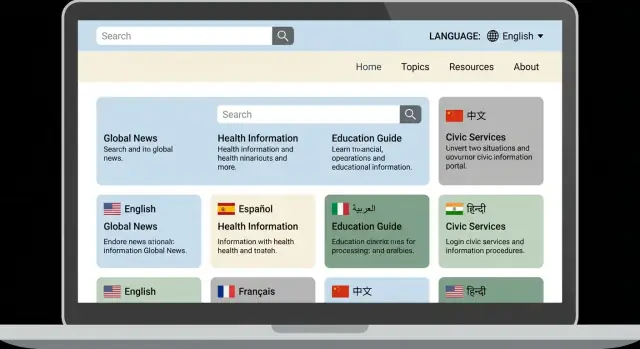

How to Create a Website for a Multi-Language Info Portal

Learn how to plan, build, and optimize a multi-language information portal: structure, translations, navigation, SEO, and ongoing updates.

Learn how to plan, build, and optimize a multi-language information portal: structure, translations, navigation, SEO, and ongoing updates.

Before you think about translation tools or a language switcher, get clear on what your portal is for and who it must serve. This step saves money later because it prevents “translate everything” decisions that don’t match real user needs.

Multi-language info portals usually fall into a few patterns:

Write a one-sentence goal, such as: “Help residents find verified services and understand eligibility requirements.” This goal becomes your filter for what gets translated first.

Languages aren’t just checkboxes. Identify:

If you have analytics or support logs, use them to confirm which languages and topics generate the most demand.

Not all content has equal value. A practical approach is to label each content type as:

Also decide what gets full localization (rewritten for clarity) versus a basic translation.

Pick a small set of measurable outcomes, for example:

These metrics will help you prioritize languages and prove the portal is working after launch.

A multilingual information portal succeeds or fails on structure. Before you translate anything, make sure the shape of the site is clear, consistent, and easy to reuse across languages.

List your content types and how they relate to each other. For most portals, this includes articles, categories, tags, help docs/FAQs, and forms (contact, feedback, newsletter, submissions). Note any special items too: legal pages, announcements, downloadable resources, or location-based pages.

Once you see everything in one place, you can decide which types must exist in every language (e.g., core help docs) and which can be optional (e.g., local news).

Aim for a site map that still makes sense when translated. A simple structure is easier to maintain and easier to navigate—especially when users switch languages mid-session.

Keep the number of top-level sections low, and avoid creating “miscellaneous” buckets that will turn into clutter later. If you need growth room, plan it as a second level under an existing section rather than adding new top-level navigation items.

Use consistent category meanings across languages (even if the labels change, the underlying concept should stay stable). This matters for navigation, search filters, analytics, and shared templates.

Be cautious with tags: they multiply quickly, are hard to translate consistently, and often become duplicates (e.g., “how-to” vs “guide”). If you use tags, define rules: who can create them, when to merge, and how to translate them.

Choose one of these models early:

If you allow language-specific sections, document them clearly so the portal doesn’t drift into three different websites over time.

Your URL pattern is one of the hardest multilingual decisions to change later. Pick a structure that stays clear as you add more languages, sections, and contributors.

1) Subdirectories: /en/, /es/, /fr/

This is the most common choice for multilingual information portals because everything lives under one domain. It’s simpler to maintain, easier to track in one analytics property, and usually the least expensive operationally.

2) Subdomains: en.example.com, es.example.com

Useful when teams, infrastructure, or release cycles are separated by locale. The downside is that each subdomain can feel like a separate site to users and tools, increasing overhead for SEO, analytics, cookies, and governance.

3) Separate domains: example.es, example.fr (or entirely different domains)

Best when you need strong country branding, local legal requirements, or local hosting. It’s also the most work: multiple domains, separate authority building, and more complex governance.

For most portals, use subdirectories (e.g., /en/, /es/) and keep the same content structure across languages.

Choose subdomains if languages are effectively run as semi-independent properties.

Choose separate domains only when there’s a clear business or legal reason.

Use human-friendly slugs, keep them stable, and mirror the hierarchy:

/en/help/getting-started//es/ayuda/primeros-pasos/Decide whether slugs are translated (often best for users) and document the rule so editors don’t drift.

Set one default behavior (e.g., redirect / to /en/ or show a language selector) and be consistent.

Avoid duplicate pages that differ only by tracking parameters or alternate paths. Use 301 redirects for retired URLs, and canonical tags to point to the preferred version when duplicates are unavoidable (for example, print views or filtered listings).

A multilingual portal only feels “easy” when people can change language without thinking about it. The language switcher isn’t decoration—it’s a core navigation element that should be consistent across the site.

Place a clear language switcher in the header so it’s visible on every page, including landing pages from search. Add a second switcher in the footer as a backup for users who scroll (and for pages with busy headers).

Prefer plain, recognizable language names (“English”, “Español”, “Français”) over flags. Flags represent countries, not languages, and they can create confusion (for example, Spanish vs. Mexico vs. Spain).

Auto-detect language carefully: you can suggest a language based on the browser setting or location, but never force a redirect that traps users. A common pattern is a subtle banner: “Prefer Español? Switch to Spanish.” If they dismiss it, don’t show it again for a while.

Once a user selects a language, remember it across sessions with a cookie (and, if you have accounts, also store it in their profile). The goal is simple: after someone picks a language once, the site should stay that way until they change it.

Plan for missing pages. When a page isn’t available in a language:

This avoids dead ends while keeping trust—and it prevents the switcher from feeling “broken” when translations are still in progress.

Your CMS choice will either make multilingual publishing feel routine—or turn every update into a mini-project. Before you compare platforms, write down what you’ll publish (news, guides, PDFs, alerts), how often it changes, and who owns each language.

A “multilingual website” isn’t only translated page text. Confirm the platform can manage, per language:

Also check how the CMS handles “missing translations.” Can you publish English updates while a Spanish version is in progress, without breaking Spanish navigation?

Whether you choose a traditional CMS (like WordPress or Drupal), a hosted builder, or a headless CMS, evaluate the same capabilities:

If you’re considering a headless CMS, make sure your site team has someone who can maintain the front-end. If not, a managed CMS may be a better fit.

If you’re building a portal from scratch, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can be a practical option for prototyping and shipping the full stack quickly: you can describe the multilingual IA, URL structure (like /en/, /es/), and core templates in chat, then iterate with planning mode, snapshots, and rollback. It’s especially useful when you want a React-based web front end with a Go/PostgreSQL backend and prefer to move fast while still being able to export source code later.

Multilingual portals benefit from tighter governance. Look for:

This prevents accidental edits to the wrong language and keeps approvals consistent.

Finally, confirm the CMS plays nicely with tools you already use (or will need):

A quick pilot—translating a few pages, a menu, and metadata end-to-end—will reveal more than a feature checklist ever will.

A multilingual info portal stays trustworthy only if every language is updated consistently. That takes more than “send it to translation”—it needs clear rules, ownership, and a predictable pipeline.

Start with a lightweight style guide that every translator and editor can follow. Keep it practical:

This reduces “same concept, three different translations” and makes search and support easier.

Most portals use a mix:

Define which content types go where. If you’re unsure, start strict (more human review) and loosen later based on quality.

Make the handoffs explicit: translator → editor → publisher.

Editors should check meaning, tone, terminology, and basic usability (links, headings, CTAs). Publishers ensure the page renders correctly and matches the source version’s intent.

Add simple acceptance criteria: “No missing strings, all buttons translated, screenshots avoided or localized, metadata included.”

The fastest way to lose user trust is having one language “stuck” months behind. Build a routine:

Consistency beats heroics here: regular checks and clear ownership prevent language versions from drifting apart.

A multilingual portal can have perfect translations and still feel “wrong” if the design assumes one language. The good news: most design localization fixes are straightforward when you plan for them early.

Some languages expand text significantly (German often gets longer; Russian can increase line length; some Asian languages may need larger font sizes for readability). Word order also changes—buttons like “Learn more” may become a longer phrase.

Design to flex:

A font that looks great in English may have missing Cyrillic, Greek, Vietnamese diacritics, or poor readability at small sizes. Choose a font family (or a paired set) that covers the full character set you need.

Practical checks:

If Arabic or Hebrew is on your roadmap, plan for RTL now—even if you launch later. RTL support isn’t just mirrored text; it affects navigation order, icons, and alignment.

Key considerations:

Formatting is part of trust. Show information the way users expect:

Treat these as design elements: reserve enough space, avoid ambiguous formats, and keep consistency across pages and forms.

Multilingual SEO is mostly about clarity: helping search engines understand which page matches which language (and sometimes which region), and making sure each version is genuinely useful.

Don’t translate only the body copy. Each language version needs its own:

Aim for natural phrasing, not word-for-word translation. A literal title can hurt click-through rate even if rankings are fine.

Add hreflang so Google can show the right language version to the right user and avoid “duplicate content” confusion across languages.

Key rules:

/en/guide and /es/guide), not just homepages.en, es, fr-CA). If you have a global default, consider x-default.If you’re not sure whether to use language-only or language+region targeting, keep it language-only until you have a strong reason to split.

Search engines reward depth and usefulness. Publishing dozens of auto-translated pages with minimal editing can create low-quality signals.

Instead:

If your platform supports it, create separate sitemaps per language (or a sitemap index). This speeds up discovery and makes it easier to debug indexing issues per locale.

Finally, verify performance in Google Search Console per language directory/subdomain and fix issues before scaling further.

A multilingual info portal succeeds or fails on “findability.” If visitors can’t locate the same topic in their language with the same mental model, they’ll assume the content doesn’t exist.

Decide early whether on-site search should be per language or cross-language.

If you’re unsure, start with per-language as the default and add an optional “include other languages” toggle later.

Set a predictable default: when a user is browsing the French version, search should return French results first. This reduces the most common frustration—typing a query and landing on content in another language.

Support this with small UI cues:

Navigation isn’t just menus. It includes category names, filters, topic tags, breadcrumbs, and “related content.” Treat these as a controlled vocabulary, not free text.

Create a shared taxonomy list (even a simple spreadsheet) that includes:

This prevents drift like “Help Center” becoming “Support,” “Assistance,” and “Customer Help” across different pages—users read that as different sections.

Your 404 page is a navigation tool, especially when links break during translation or restructuring.

A good multilingual 404 should:

If you have popular evergreen pages, include “Most visited resources” to quickly recover the session.

A multilingual info portal succeeds or fails on the “last mile” moments: submitting a request, subscribing to updates, downloading a resource, or reporting an issue. These journeys often mix UI copy, validation rules, email templates, and legal notices—so partial translation quickly feels broken.

Localize the full form experience end to end:

Also localize transactional messages that are triggered by forms: confirmation emails, password resets, and ticket acknowledgements. If the portal allows users to choose a preferred language in their profile, use that preference for emails—not the site language they happened to browse in.

Accessibility is not “one-and-done” in the source language. Each translation can change text length and meaning, which impacts usability.

Check in every language:

If you use icons (like an “i” tooltip), ensure the explanation is available to screen readers and translated.

Cookie/consent prompts and legal pages may need to vary by region. Localize the text, but also confirm the behavior (what gets blocked until consent) matches local requirements. When needed, publish region-specific pages such as Privacy Policy, Terms, and data request instructions.

Before launch, run task-based checks with native speakers (or professional reviewers): submit a form, trigger every error, complete the confirmation flow, and verify the email content. Real usage quickly reveals awkward wording, missing translations, and confusing steps that automated checks won’t catch.

A multilingual info portal isn’t “done” at launch. The difference between a site that stays trustworthy and one that slowly drifts out of sync is how you measure outcomes per language—and how disciplined your updates are.

Before you publish new pages (or a big redesign), use a repeatable checklist so every language ships at the same quality bar:

Treat this as a gate: if a language is missing a critical element, either complete it or intentionally hide that page in that language until it’s ready.

Set up reporting that can answer “How is Spanish doing?” not only “How is the site doing?” Track, by language:

This reveals whether you have a translation issue (people bounce) or a discoverability issue (no impressions).

Multilingual sites often break quietly: a new English page goes live, but the French version 404s; a slug changes, but only in one locale. Add alerts for:

Schedule quarterly audits to keep content and SEO aligned:

Consistency beats heroic cleanups—small, regular checks keep a multilingual portal reliable over time.

Start by writing a one-sentence portal goal and listing your top user journeys (e.g., eligibility, how to apply, emergency info). Then label content types as:

This prevents “translate everything” spending and keeps quality high where it matters most.

Use metrics tied to outcomes, not just pageviews. Common options include:

Set targets per language so you can see if one locale is falling behind in discovery or usability.

Start with an inventory of what you publish (articles, guides, FAQs, directories, forms, legal pages). Then design a site map that stays consistent across languages:

A consistent structure makes navigation, search, analytics, and translation workflows much easier to maintain.

Treat taxonomy as a controlled vocabulary. Define canonical concepts (e.g., “Public health”) and maintain approved translations for each language.

Practical tips:

This prevents navigation drift where similar sections get translated into different, confusing labels.

For most portals, use subdirectories (e.g., /en/, /es/). They’re typically simplest for:

Use subdomains only if locales run like semi-independent properties, and separate domains only for strong legal/business reasons.

Set one default behavior and apply it everywhere:

/ does (redirect to a default language or show a selector)Also ensure each page links to its true language equivalent (not just the homepage) so switching languages doesn’t break the user’s path.

Put a language switcher in the header on every page (and optionally in the footer as backup). Use language names like “English” and “Español,” not flags.

For auto-detection:

This keeps switching predictable and avoids frustration.

Avoid dead ends. When a page isn’t translated:

This maintains trust while translations are still in progress.

Confirm your CMS can manage, per language:

Also look for translation linking/status, per-language workflows (draft → review → publish), roles/permissions, and clean support for your chosen URL pattern.

Prioritize clarity and usefulness in each language:

Keep region targeting (like fr-CA) only when you truly have region-specific needs.