Sep 09, 2025·8 min

How to Create a SaaS Status Website with Incident History

Learn how to plan, build, and publish a SaaS status page with incident history, clear messaging, and subscriptions so customers stay informed during outages.

Learn how to plan, build, and publish a SaaS status page with incident history, clear messaging, and subscriptions so customers stay informed during outages.

A SaaS status page is a public (or customer-only) website that shows whether your product is working right now—and what you’re doing if it isn’t. It becomes the single source of truth during incidents, separate from social media, support tickets, and rumor.

It helps more people than you might expect:

A good service status website usually contains three related (but different) layers:

The goal is clarity: real-time status answers “Can I use the product?” while history answers “How often does this happen?” and postmortems answer “Why did this happen, and what changed?”

A status page works when updates are fast, plain-language, and honest about impact. You don’t need a perfect diagnosis to communicate. You do need timestamps, scope (who’s affected), and the next update time.

You’ll rely on it during outages, degraded performance (slow logins, delayed webhooks), and planned maintenance that could cause brief disruption or risk.

Once you treat the status page as a product surface (not a one-off ops page), the rest of the setup becomes a lot easier: you can define owners, build templates, and connect monitoring without reinventing the process during every incident.

Before you pick a tool or design a layout, decide what your status page is supposed to do. A clear goal and a clear owner are what keep status pages useful during an incident—when everyone is busy and information is messy.

Most SaaS teams create a status page for three practical outcomes:

Write down 2–3 measurable signals you can track after launch: fewer duplicate tickets during outages, faster time-to-first-update, or more customers using subscriptions.

Your primary reader is usually a non-technical customer who wants to know:

That means minimizing jargon. Prefer “Some customers can’t log in” over “Elevated 5xx rates on auth.” If you do need technical detail, keep it as a short secondary sentence.

Pick a tone you can maintain under pressure: calm, factual, and transparent. Decide upfront:

Make ownership explicit: the status page should not be “everyone’s job,” or it becomes no one’s job.

You have two common options:

If your main app can go down, a standalone status site is usually safer. You can still link to it prominently from your app and help center (for example, /help).

A status page is only as useful as the “map” behind it. Before you pick colors or write copy, decide what you’re actually reporting on. The goal is to reflect how customers experience your product—not how your org chart is arranged.

List the pieces a customer might describe when they say “it’s broken.” For many SaaS products, a practical starting set looks like:

If you offer multiple regions or tiers, capture that too (e.g., “API – US” and “API – EU”). Keep names customer-friendly: “Login” is clearer than “IdP Gateway.”

Choose a grouping that matches how customers think about your service:

Try to avoid an endless list. If you have dozens of integrations, consider one parent component (“Integrations”) plus a few high-impact children (e.g., “Salesforce,” “Webhooks”).

A simple, consistent model prevents confusion during incidents. Common levels include:

Write internal criteria for each level (even if you don’t publish it). For example, “Partial Outage = one region down” or “Degraded = p95 latency above X for Y minutes.” Consistency builds trust.

Most outages involve third parties: cloud hosting, email delivery, payment processors, or identity providers. Document these dependencies so your incident updates can be accurate.

Whether to display them publicly depends on your audience. If customers can be directly impacted (e.g., payments), showing a dependency component can be helpful. If it adds noise or invites blame games, keep dependencies internal but reference them in updates when relevant (e.g., “We are investigating elevated errors from our payment provider”).

Once you have this component model, the rest of your status page setup becomes much easier: every incident gets a clear “where” (component) and “how bad” (status) from the start.

A status page is most useful when it answers customer questions in seconds. People typically arrive stressed and want clarity—not a lot of navigation.

Prioritize the essentials at the very top:

Write in plain language. “Elevated error rates on API requests” is clearer than “Partial outage in upstream dependency.” If you must use technical terms, add a short translation (“Some requests may fail or time out”).

A reliable pattern is:

For the component list, keep labels customer-facing. If your internal service is “k8s-cluster-2,” customers likely need “API” or “Background Jobs.”

Make the page readable under pressure:

Place a small set of links near the top (header or right under the banner):

The goal is confidence: customers should immediately understand what’s happening, what it affects, and when they’ll hear from you next.

When an incident hits, your team is juggling diagnosis, mitigation, and customer questions at the same time. Templates remove guesswork so updates stay consistent, clear, and fast—especially when different people might be posting.

A good update starts with the same core facts every time. At minimum, standardize these fields so customers can quickly understand what’s going on:

If you publish an incident history page, keeping these fields consistent makes past incidents easy to scan and compare.

Aim for short updates that answer the same questions customers have every time. Here’s a practical template you can copy into your status page tool:

Title: Brief, specific summary (e.g., “API errors for EU region”)

Start time: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM (TZ)

Affected components: API, Dashboard, Payments

Impact: What users are seeing (errors, timeouts, degraded performance) and who is affected

What we know: One sentence on the cause if confirmed (avoid speculation)

What we’re doing: Concrete actions (rollback, scaling, vendor escalation)

Next update: Time you’ll post again

Updates:

Customers don’t just want information—they want predictability.

Planned maintenance should feel calm and structured. Standardize maintenance posts with:

Keep maintenance language specific (what changes, what users might notice), and avoid overpromising—customers value accuracy over optimism.

An incident history page is more than a log—it’s a way for customers (and your own team) to quickly understand how often issues happen, what types of problems repeat, and how you respond.

A clear history builds confidence through transparency. It also creates trend visibility: if you see recurring “API latency” incidents every few weeks, that’s a signal to invest in performance work (and to prioritize a post-incident review process). Over time, consistent reporting can reduce support tickets because customers can self-serve answers.

Pick a retention window that matches your customer expectations and product maturity.

Whatever you choose, state it clearly (e.g., “Incident history is retained for 12 months”).

Consistency makes scanning easy. Use a predictable naming format such as:

YYYY-MM-DD — Short summary (e.g., “2025-10-14 — Delayed email delivery”)

For each incident, show at least:

If you publish postmortems, link from the incident detail page to the write-up (for example: “Read the postmortem” linking to /blog/postmortems/2025-10-14-email-delays). This keeps the timeline clean while still offering detail for customers who want it.

A status page is helpful when customers think to check it. Subscriptions flip that around: customers get updates automatically, without refreshing the page or emailing support for confirmation.

Most teams expect at least a couple of options:

If you support multiple channels, keep the setup flow consistent so customers don’t feel like they’re signing up four different ways.

Subscriptions should always be opt-in. Be explicit about what people will receive before they confirm—especially for SMS.

Give subscribers control over:

These preferences reduce alert fatigue and keep your notifications trusted. If you don’t have component-level subscriptions yet, start with “All updates” and add filtering later.

During an incident, message volume spikes and third-party providers can throttle traffic. Double-check:

It’s worth running a scheduled test (even quarterly) to ensure subscriptions still work as expected.

Add a clear callout on the status homepage—above the fold if possible—so customers can subscribe before the next incident. Make it visible on mobile, and include it in places where customers look for help (like a link from your support portal or /help center).

Picking how you’ll build your status page is less about “can we build it?” and more about what you want to optimize for: speed to launch, reliability during incidents, and ongoing maintenance effort.

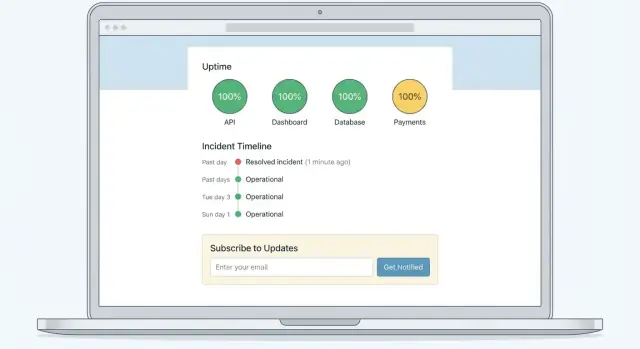

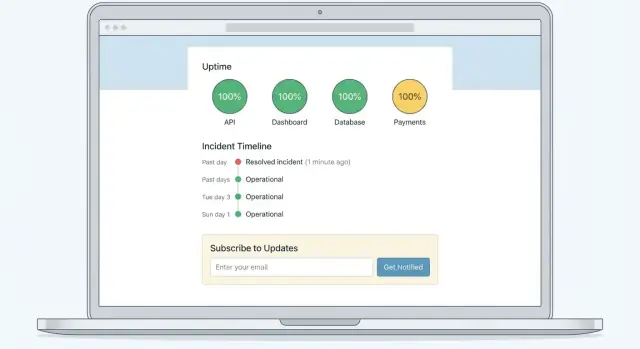

A hosted tool is usually the fastest path. You get a ready-made status page, subscriptions, incident timelines, and often integrations with common monitoring systems.

What to look for in a hosted tool:

DIY can be a great choice if you want full control over design, data retention, and how incident history is presented. The trade-off is you own reliability and operations.

A practical DIY architecture is:

If you self-host, plan for failure modes: what happens if your primary database is unavailable, or your deploy pipeline is down? Many teams keep the status page on separate infrastructure (or even a separate provider) from the main product.

If you want the control of DIY without rebuilding everything from scratch, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you stand up a custom status site (web UI plus a small incident API) quickly from a chat-driven spec. That’s especially useful for teams who want tailored component models, custom incident history UX, or internal admin workflows—while still being able to export source code, deploy, and iterate fast.

Hosted tools have predictable monthly pricing; DIY has engineering time, hosting/CDN costs, and ongoing maintenance. If you’re comparing options for your team, outline the expected monthly spend and the internal time you’ll need—then sanity-check it against your budget (see /pricing).

A status page is only useful if it reflects reality quickly. The easiest way to do that is to connect the systems that detect problems (monitoring) with the systems that coordinate your response (incident workflow), so updates are consistent and timely.

Most teams combine three data sources:

A practical rule: monitoring detects; incident workflow coordinates; the status page communicates.

Automation can save minutes when it matters:

Keep the first public message conservative. “Investigating elevated errors” is safer than “Outage confirmed” when you’re still validating.

Fully automated messaging can backfire:

Use automation to draft and suggest updates, but require a human to approve customer-facing wording—especially for Identified, Mitigated, and Resolved states.

Treat the status page like a customer-facing logbook. Ensure you can answer:

This audit trail helps with post-incident review, reduces confusion during handoffs, and builds trust when customers ask for clarification.

A status page only helps if it’s reachable when your product isn’t. The most common failure mode is building the status site on the same infrastructure as the app—so when the app goes down, the status page vanishes too, leaving customers with no source of truth.

When possible, host the status page on a different provider than your production app (or at least a different region/account). The goal is blast-radius separation: an outage in your app platform shouldn’t also take down your incident communications.

Also consider separating DNS. If your main domain’s DNS is managed in the same place as your app edge/CDN, a DNS or certificate issue can block both at once. Many teams use a dedicated subdomain (for example, status.yourcompany.com) with DNS hosted independently.

Keep assets lightweight: minimal JavaScript, compressed CSS, and no dependencies that require your app’s APIs to render. Put a CDN in front of the status page and enable caching for static resources so it loads even under heavy traffic during incidents.

A practical safety net is a fallback static mode:

Customers shouldn’t need to log in to see service health. Keep the status page public, but put your admin/editor tools behind authentication (SSO if you have it), with strong access controls and audit logs.

Finally, test failure scenarios: temporarily block your app origin in a staging environment and confirm the status page still resolves, loads quickly, and can be updated when you need it most.

A status page only builds trust if it’s consistently updated during real incidents. That consistency doesn’t happen by accident—you need clear ownership, simple rules, and a predictable cadence.

Keep the core team small and explicit:

If you’re a small team, one person can hold two roles—just decide in advance. Document role handoffs and escalation paths in your on-call handbook (see /docs/on-call).

When an alert turns into a customer-impacting incident, follow a repeatable flow:

A practical rule: post the first update within 10–15 minutes, then every 30–60 minutes while impact continues—even if the message is “No change, still investigating.”

Within 1–3 business days, run a lightweight post-incident review:

Then update the incident entry with the final summary so your incident history stays useful—not just a log of “resolved” messages.

A status page is only useful if it’s easy to find, easy to trust, and consistently updated. Before you announce it, do a quick “production-ready” pass—and then set up a lightweight cadence to improve it over time.

Copy and structure

Branding and trust

Access and permissions

Test the full workflow

Announce

If you’re building your own status site, consider running the same launch checklist in a staging environment first. Tools like Koder.ai can speed up this iteration loop by generating the web UI, admin screens, and backend endpoints from a single spec—then letting you export the code and deploy it wherever you need.

Track a few simple outcomes and review them monthly:

Keep a basic taxonomy so history becomes actionable:

Over time, small improvements—clearer wording, faster updates, better categorization—compound into fewer interruptions, fewer tickets, and more customer confidence.

A SaaS status page is a dedicated page that shows current service health and incident updates in one canonical place. It matters because it reduces “Is it down?” support load, sets expectations during outages, and builds trust with clear, timestamped communication.

Real-time status answers “Can I use the product right now?” with component-level states.

Incident history answers “How often does this happen?” with a timeline of past incidents and maintenance.

Postmortems answer “Why did it happen and what changed?” with root cause and prevention steps (often linked from the incident entry).

Start with 2–3 measurable outcomes:

Write these goals down and review them monthly so the page doesn’t become stale.

Assign an explicit owner and a backup (often the on-call rotation). Many teams use:

Also define rules in advance: who can publish, whether approvals are required, and your minimum update cadence (for example, every 30–60 minutes during major incidents).

Choose components based on how customers describe problems, not internal service names. Common components include:

If reliability differs by geography, split by region (for example, “API – US” and “API – EU”).

Use a small, consistent set of levels and document internal criteria for each:

Consistency matters more than perfect precision. Customers should learn what each level means based on repeated, predictable usage.

A practical incident update should always include:

Even if you don’t know the root cause yet, you can still communicate scope, impact, and what you’re doing next.

Post an initial “Investigating” update quickly (often within 10–15 minutes of confirmed impact). Then:

If you’re going to miss your cadence, post a brief note resetting expectations rather than going silent.

Hosted tools optimize for speed and reliability (often staying online even if your app is down) and usually include subscriptions and integrations.

DIY can give full control but you must design for resilience:

Offer the channels customers already rely on (commonly email and SMS, plus Slack/Teams or RSS). Keep subscriptions opt-in and clarify:

Test deliverability and rate limits periodically so notifications still work when traffic spikes during an incident.