Aug 06, 2025·8 min

Create a Website Today That Can Grow Into a Product Later

Learn how to design a simple website today that can grow into a real product later—without rewrites—using clear goals, data, and modular choices.

Learn how to design a simple website today that can grow into a real product later—without rewrites—using clear goals, data, and modular choices.

A “website that can become a product” is built with a clear path to something more than pages: a repeatable experience people can return to, pay for, and rely on. Early on, it may look like a simple marketing site or a polished MVP website. Over time, it evolves into a product interface—often without needing to throw everything away.

It is a way to validate demand while keeping future options open: clear positioning, structured content, and data capture that can later power onboarding, personalization, or paid access.

It is not “build the whole app now.” Planning for growth doesn’t mean shipping complex features before you understand the customer. If you overbuild, you create a different kind of rework: maintaining functionality nobody asked for.

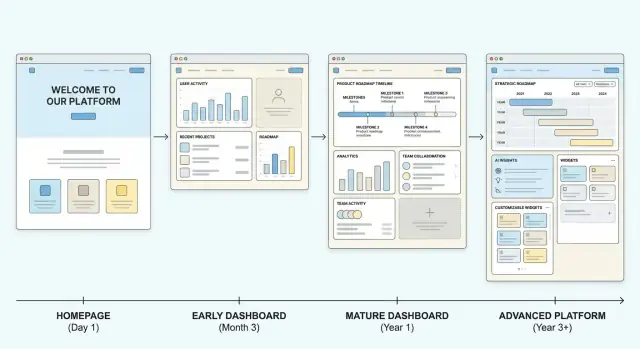

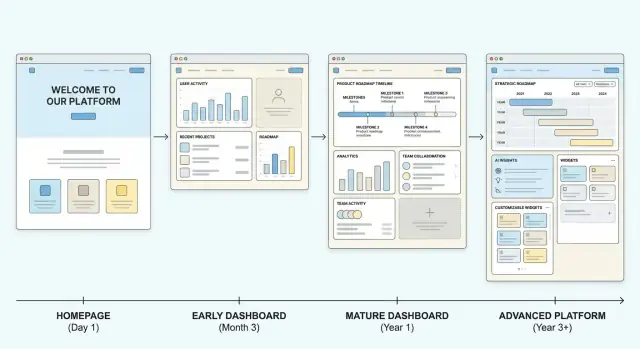

Most teams follow a progression like this:

This “content → lead capture → workflow → app” path is how many website-to-product stories actually happen: validation with increasing commitment.

Plan early:

Wait on:

Those should be driven by real user feedback loops and analytics for early products.

This approach is ideal for founders, marketers, and small teams who need momentum now but don’t want to corner themselves later.

The outcome isn’t perfection—it’s less rework while you validate demand, so when you do build product features, you’re building on evidence rather than guesses.

A site that can grow into a product starts with focus. Not “we help everyone,” but a specific person with a specific job they’re trying to get done. When you can name that job clearly, you can design a site that behaves like an early product: it makes a promise, guides people to one action, and produces measurable learning.

Define one primary user. Not an audience segment list—one person you’re building for first. Then describe the job they’re hiring a solution for in plain language.

Example:

This keeps you from building a generic marketing site. It also gives you a north star for later product decisions: any feature that doesn’t help this user do this job is a “not yet.”

Your value proposition should fit on one line and be testable.

Template: “We help [target user] achieve [desired outcome] without [major pain/cost].”

Then add three supporting points that explain why it’s believable. Keep them concrete:

These supporting points often become your first homepage sections, pricing bullets, and future onboarding copy.

Pick a single action that matches where you are today:

Design everything to support that one action: page structure, navigation, and calls to action. Secondary links are fine, but they should never compete with your main goal.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t learn from it. Choose 2–4 metrics that reflect progress, such as:

These metrics become the early validation system that tells you whether to iterate, reposition, or double down.

Write a short “not yet” list and treat it as protection, not limitation. Examples: account dashboards, multi-role permissions, a mobile app, advanced integrations. This keeps the website lightweight while leaving room for a real product roadmap based on evidence—not guesses.

A site with a product future should guide people through a simple, repeatable journey: first visit → trust → action → follow-up. Think less like “pages” and more like a path that turns curiosity into a measurable next step.

Start by deciding what you want a first-time visitor to do. For an early-stage product, the best actions are usually: start a trial, join a waitlist, request a demo, or book a call. Everything else should support that single action.

A useful funnel structure is:

Resist building a big site. Most teams need only:

Add optional pages only if they answer repeated questions. Common ones are FAQ and Use Cases—but only when you already hear those questions from real people.

Every page should have one main CTA (with optional secondary links kept subtle). Keep navigation to a few top-level items so you can add new sections later without a redesign—your menu can expand into “Solutions,” “Resources,” or “Product” when the offering grows.

A website that can grow into a product shouldn’t be a collection of one-off pages. Think in reusable “blocks” you can rearrange as your MVP evolves, your messaging changes, and new features arrive.

Create a small library of sections you can reuse across pages:

When you repeat these blocks, visitors learn how to scan your site faster—and you avoid redesigning every time you test positioning.

Use the same heading levels, spacing rules, and component styles everywhere (buttons, cards, forms, badges). The payoff is practical: new pages feel cohesive, and future “product pages” won’t require a full refresh.

A lightweight style guide is enough:

Plan visible placeholders for what’s likely coming next—without pretending you already built it. Examples:

This makes the website-to-product transition smoother because your layout already anticipates new content.

Write copy in self-contained chunks (headline, one-paragraph explanation, 3 bullets). That way you can swap positioning or add “build in public” updates without touching the layout—or breaking your scalable content strategy.

The “right” tech for a future product isn’t the fanciest stack—it’s the one you can upgrade without rebuilding everything. Start simple, but make a few intentional choices so your site can evolve into an MVP product when you’re ready.

A modern CMS (or a quality site builder) is often the fastest path to launch—especially if your first job is explaining the offer and collecting leads. If you’re already technical, a lightweight framework can be fine too. The key question: can you migrate content and keep URLs stable later?

A practical rule: pick tools that export content cleanly (API access, CSV export, or structured collections), not just “pages.”

If you expect to move from marketing site to working app quickly, consider tools that let you build both without a full rewrite. For example, Koder.ai is a vibe-coding platform where you can go from a chat-based spec to a working web app (React frontend, Go backend, PostgreSQL) and iterate fast as your requirements become real. It also supports source code export, snapshots, and rollback—useful when you’re evolving a live site into product functionality.

Even if you’re a one-person team, treat content like data. Use CMS collections/fields for things like:

This keeps you from rewriting everything when the site becomes more dynamic.

Pricing is the classic trap. Don’t bake pricing tiers into custom HTML that’s painful to change. Same for feature matrices, integrations, testimonials, and “what’s included.” If it could later be personalized, filtered, or tied to an account—store it as structured content.

Choose a platform that lets you control slugs and set 301 redirects. When you later move from a marketing site to a product app, your best-performing pages should keep their URLs (or redirect cleanly). This prevents traffic losses right when you need momentum.

Move beyond static when you see clear signals, like:

Until then, keep the stack light and focus on learning.

A signup form isn’t just for “leads.” If you design it well, it becomes your fastest product research channel—because it attracts people who already want the outcome you plan to sell.

Keep the form short and purposeful. Every field should drive a follow-up action or a clear segmentation decision.

Ask for:

If you can’t explain how a field changes your next step, remove it.

Instead of a generic “Join our newsletter,” offer a waitlist that helps you understand demand. Add 1–2 lightweight segmentation inputs:

This lets you prioritize which segment to build for first—and tailor follow-ups without writing different websites.

Some visitors are ready now. Give them a clear next step:

You’ll learn more from five real conversations than 500 anonymous pageviews.

Your confirmation email should do two jobs:

Start with a lightweight CRM—or even a spreadsheet—with columns like:

This turns lead capture into a living backlog of validated needs, not a pile of emails.

If you want the website-to-product journey to be smooth, you need proof—early and continuously—of what people try to do on your site and what stops them. Analytics gives you the “what.” Feedback gives you the “why.” Together, they turn your website into a learning system instead of a static brochure.

Pageviews are fine, but they don’t tell you intent. Define a small set of events tied to your primary goal and product validation:

Keep the list short so you actually use it. If everything is “important,” nothing is.

Create a simple dashboard that answers: “Where are visitors coming from, and do they do the thing?” At minimum:

This baseline is your reference point. Without it, every change can feel like progress—even when it isn’t.

Numbers won’t tell you why someone hesitated. Add one qualitative channel:

Save the answers in a place your team will read weekly (not buried in an inbox).

Pick a consistent time each week to review signals, choose one change, and set a clear expectation (your hypothesis). Example: “If we clarify the promise above the fold, pricing views will increase.” Run one test at a time so you can attribute results.

High traffic can hide low-quality demand. Prioritize indicators of real intent: repeat visits, pricing engagement, demo requests, and people returning after you follow up. Those are the behaviors that help you graduate from an MVP website to an early product with confidence.

Trust is an asset you can build early—then keep using when you shift from “service website” to “product.” The goal is to reduce uncertainty without overpromising.

Start with a simple statement: who it’s for, what problem you solve, and what outcome people should expect. Avoid vague claims like “best” or “guaranteed.” If you can’t prove it, don’t say it.

If you have screenshots, use real ones. If you only have concepts, that’s okay—label them as mockups. A small line like “Concept UI (mockup)” protects credibility and prevents awkward conversations later.

Social proof works, but it’s fragile. Add it carefully:

If you’re early, use “proof of work” instead: before/after examples, a short case study, or a simple breakdown of what changed and what result it produced.

People hesitate when they don’t know what happens after they click.

Use a short “How it works” block that covers: the timeline, what the customer needs to provide, what you deliver, and who it’s not for. This section transitions well later into onboarding for a product.

Link to a deeper page if needed (for example, /how-it-works), but keep the essentials on the main path.

You don’t need perfect pricing—you need understandable pricing. If you’re still validating, use “Starting at,” “Pilot pricing,” or “Limited early access.” The key is to set expectations about ranges, what’s included, and what would increase cost.

Clear pricing also helps product discovery: the questions people ask about price are often hints about what they truly value.

Your contact page shouldn’t be a dead end. Include:

This becomes even more important later when support shifts from “talk to the founder” to “support for a product.”

A website can feel “done” once it looks good and starts generating leads. But if you want it to grow into a product, treat the site as the front door to a service you can deliver today—manually or semi-manually—while you learn what customers actually need.

Begin with a simple offer you can fulfill using everyday tools: a form, email, a calendar link, and a spreadsheet. The goal isn’t to build software immediately—it’s to prove you can consistently deliver an outcome and understand what “success” means for your customers.

For example, if your future product is “automated reporting,” start with a paid reporting service. Collect inputs via a form, produce the report manually, and deliver it via email. You’ll quickly find what data people struggle to provide, what format they prefer, and what questions they ask every time.

As you fulfill requests, write down the steps you repeat. Keep it lightweight: a checklist in a doc is enough. Over time, this becomes your blueprint for product features because it captures:

Pay attention to friction points: tasks that take too long, cause errors, or delay delivery. These are your best signals for what to automate first.

Common “pain” metrics to track in your spreadsheet:

Resist the urge to build lots of features. Productize the single bottleneck that saves the most time or reduces the most confusion. That first workflow might be as small as an onboarding form that validates inputs, a status page for customers, or a templated deliverable generator.

If you want to capture this process publicly, add a simple “How it works” section on your site and iterate it as you learn.

A roadmap matters—but not the kind built from opinions, competitor envy, or internal brainstorming. Your roadmap should translate real user behavior and real requests into a small set of bets you can ship quickly.

Keep the roadmap intentionally small and easy to explain:

When a feature request appears, score it using three inputs:

If it’s not high on at least two of these, it’s probably not a “Now” item.

Your MVP isn’t “the smallest app.” It’s the smallest outcome. Aim for something deliverable in weeks, not months—often a guided flow, a limited self-serve feature, or one repeatable template.

If you’re trying to compress build cycles while you learn, tools like Koder.ai can help you prototype the “Next” items quickly (for example, a basic dashboard, onboarding flow, or internal admin panel) and iterate from customer feedback—without committing to a long build pipeline upfront.

A good rule: make repetitive, low-risk steps self-serve, and keep high-trust, high-stakes steps assisted (at least early on).

If a feature doesn’t support the core goal—or can’t be measured against it—say no (or “later”). Protect focus so you evolve with momentum, not complexity.

SEO is easier when your site is small—so use that stage to make structural decisions you won’t regret later. The goal isn’t to publish a lot; it’s to publish the right pages, with clean URLs and clear intent, so you can expand into a product without rebuilding your navigation or changing what search engines already understand about you.

Write page titles and H1s the way your audience searches, not the way you describe yourself internally. A good test: could someone read the title and immediately know what problem it helps solve?

For example, a product-oriented homepage title like “Acme — Inventory tracking for small warehouses” is clearer than “Acme — Modern operations platform.” Keep the main keyword close to the front, and make sure each page has one obvious topic.

A scalable content strategy starts with a few foundational pieces that cover high-intent questions:

Each article should naturally point to a next step—usually /pricing, /contact, or a signup page—so content isn’t just “traffic,” it’s part of product validation.

If you publish in public (updates, teardown posts, lessons learned), consider formalizing it: some platforms—including Koder.ai—offer ways to earn credits by creating content or referring other users. That can make “build in public” a little more sustainable while you’re still early.

Changing URLs later is one of the most common “SEO rewrites.” Avoid it by choosing a simple structure now:

Stability matters more than cleverness. If you’re unsure, pick the simplest structure you can keep for years.

Internal links help users discover your funnel and help search engines understand what matters. Make it a habit to link:

Keep links relative (like /pricing), so they remain valid across environments.

It’s tempting to create pages for features you plan to build to attract searches. But misleading pages increase bounce, erode trust, and can create a messy site you later have to clean up. If you must mention upcoming capabilities, do it transparently on a /roadmap page or inside a FAQ—without pretending it already exists.

You don’t have to “build the product” on day one. A better approach is to ship a credible site first, then add product-like behavior in steps—each one validating demand and reducing risk.

Start with a site that explains the problem, your promise, and the next step. Pick one primary conversion (book a call, join a waitlist, request a demo) and make it obvious.

Keep pages lean: Home, Pricing/How it works, About, and a simple contact path. Your site’s job here is clarity, not features.

Add a lightweight “product taste.” This can be a gated guide, an assessment, a template library, or a short onboarding questionnaire that ends with early access.

The goal: learn who wants this and why—before you build accounts or complex flows.

Introduce a basic logged-in area: saved results, a dashboard with a few actions, or a client portal. Pair it with a real transaction, even if the “product” is still partly manual.

Common options:

If you’re moving into this phase and want speed without locking yourself into a dead-end prototype, a platform like Koder.ai can help you stand up a working account area quickly, iterate with snapshots/rollback, and export the source code once you’re ready for a longer-term codebase.

Now expand into the complete product: deeper functionality, self-serve onboarding, and the “unsexy” parts that prevent chaos—documentation, support, and reliable operations.

Add /docs (or a help center) and define support channels, response times, and escalation paths.

Use this checklist before moving to the next phase:

It’s a site designed to validate demand now (clear positioning, measurable conversions, lead capture) while keeping structure and technology flexible enough to add workflows, accounts, and paid access later—without rebuilding from scratch.

Because premature complexity creates a different kind of rework: you end up maintaining features nobody asked for. Start with the smallest experience that proves a real outcome, then add product capabilities only when behavior and conversations justify them.

A common progression is:

Each step increases commitment only after you’ve earned it with evidence.

Start with one primary user and one “job to be done,” then write a one-sentence value proposition: “We help [target user] achieve [outcome] without [pain/cost].” Add 3 concrete supporting points and build the site around that message.

Pick one action that matches your stage and design the entire funnel around it (CTA, navigation, page order, follow-up).

Good options include:

Everything else should be secondary and non-competing.

Keep it lean:

Add pages like FAQ or Use Cases only when they answer questions you repeatedly hear.

Use reusable blocks (hero, benefits, social proof, comparison) and consistent styles (typography, spacing, button types). Store frequently updated items (pricing, features, testimonials, FAQs) as structured content so you can later personalize, filter, or connect them to logged-in experiences.

Choose tools that:

Avoid hard-coding things that will change often (pricing tables, feature matrices). This preserves SEO and makes later app transitions smoother.

Track a small set of intent-focused events:

Pair analytics with one qualitative channel (a single-question survey or a post-submit prompt). Review weekly and run one test at a time with a clear hypothesis.

Keep it short and purposeful:

Use confirmation emails to set expectations and ask one more thing (e.g., “Reply with your biggest challenge”). Track responses in a simple CRM or spreadsheet so leads become product discovery.