Dec 13, 2025·8 min

Daniel Ek’s Spotify: Two-Sided Markets, Licensing, Personalization

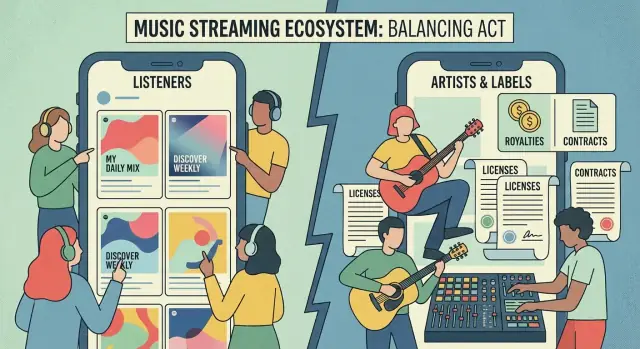

How Spotify scaled under Daniel Ek: balancing listeners and rights holders, negotiating licensing, and using personalization to grow into a global media tech platform.

What Made Spotify Different Under Daniel Ek

Spotify is often described as a “music streaming app,” but a more useful frame is a media tech platform that coordinates listeners, creators, rights holders, advertisers, and device makers. Under Daniel Ek, the differentiator wasn’t a single feature—it was a system designed to make access feel instant, discovery feel personal, and the business model workable at global scale.

Three lenses for understanding Spotify

This article uses three lenses to explain why Spotify could grow where many earlier services stalled:

- Two-sided markets: Spotify serves listeners on one side and the music industry (rights holders and creators) on the other—while also involving advertisers and distribution partners.

- Licensing strategy: The product is inseparable from the deal structure that makes the catalog available. Licensing isn’t “legal plumbing”; it shapes margins, user experience, and what can ship.

- Personalization: Recommendations aren’t an algorithmic add-on. Personalization is a product strategy that improves retention, reduces churn, and increases the perceived value of the catalog.

Facts vs. analysis

Where possible, this sticks to publicly known facts (e.g., Spotify operates on licensed music catalogs, runs a freemium tier supported by ads, and invests heavily in personalization and discovery features). The rest is analysis: how these choices interact, what incentives they create, and why certain trade-offs recur.

The core trade-offs Spotify has managed

Spotify’s “different” has always been about balancing tensions: free access vs. paid conversion, growth vs. royalty cost, personalization vs. editorial control, global expansion vs. local licensing realities, and platform scale vs. dependence on major rights holders. The sections ahead unpack how these trade-offs connect—and why solving them requires both product thinking and deal-making.

Spotify as a Two-Sided Market: Who the Platform Serves

Spotify isn’t just selling music streaming to listeners; it’s balancing two groups that need each other but want different outcomes. That’s the defining feature of a two-sided market: the product is the matchmaker, and the “customer” is really two customers.

The two sides: listeners and rights holders

On one side are listeners who want instant access to a huge catalog, on any device, at a price that feels fair (or free). On the other side are rights holders—record labels, music publishers, and increasingly independent artists—who control the catalog Spotify needs to be worth using.

What each side cares about

Listeners care about convenience, breadth of catalog, predictable pricing, and a frictionless experience. If the catalog is missing key artists or albums, the service feels incomplete.

Rights holders care about reach (audience scale), revenue (royalties), and discovery. Spotify’s promise isn’t only “we’ll pay you,” but “we’ll help the right listeners find you,” which can translate into sustained streaming over time.

Feedback loops: how each side moves the other

When Spotify grows listeners, it becomes a bigger paycheck and a bigger marketing channel for rights holders, making them more willing to license content and support releases on the platform. A stronger catalog then makes Spotify more attractive to listeners—a positive loop.

But the loop can also turn negative. If royalties are perceived as too low—or if the platform is seen as favoring certain content—rights holders may restrict licensing, window releases, or push audiences elsewhere, hurting listener value.

Common failure modes

Two-sided markets often stall due to a chicken-and-egg problem: listeners won’t come without a catalog, and rights holders won’t commit without listeners. Another trap is pricing imbalance—optimizing for listener growth (cheap/free) without a credible, transparent path to rights-holder value can create long-term friction and churn on the supply side.

Network Effects and the Streaming Flywheel

Network effects happen when a service becomes more valuable as more people use it. In music streaming, that value doesn’t come from “more users” alone—it shows up through practical channels: a broader and fresher catalog, better support across phones/cars/speakers, and more social proof when people share what they’re listening to.

What “network effects” look like in streaming

- Catalog breadth and freshness: More listening gives a platform more leverage (and data) to justify investing in licensing, faster releases, and priority partnerships.

- Device support: A streaming app that’s available everywhere—mobile, desktop, smart TVs, game consoles, car systems—wins more daily minutes. Those minutes compound.

- Social sharing: Playlists and links passed between friends create lightweight acquisition. Even when sharing happens outside the app, the platform that’s easiest to open and play tends to capture the habit.

Multi-homing: the hidden constraint

Most listeners multi-home: they keep multiple services (Spotify plus YouTube, Apple Music, or a radio app). That weakens pure “winner-take-all” network effects. If switching is easy, network effects alone won’t lock the market.

So the game becomes: make your service the default, even if users keep others.

Switching costs that actually stick

Spotify’s defensibility is partly built from accumulated choices:

- Playlists and saved libraries (time invested)

- Recommendations that adapt to personal taste (learning invested)

- Downloads and offline routines (habit invested)

These aren’t contractual lock-ins; they’re psychological and practical. The longer someone listens, the more the service “fits.”

The streaming flywheel (in words)

More listeners → more listening data → better personalization and discovery → more listening time and retention → stronger negotiating position and investment in catalog + devices → an even better service for listeners (and more value for artists/labels) → more listeners.

Freemium: Turning Free Listening Into Paid Retention

Spotify’s freemium model wasn’t “free music” as charity—it was a deliberate way to turn streaming into a daily habit, then monetize that habit in multiple ways. The free tier expanded reach quickly, while Premium captured the heaviest listeners who valued convenience and control.

Why “free” is valuable beyond revenue

Free listening functions like a low-friction trial, but it’s more than sampling. It helps users build playlists, follow artists, and make Spotify their default player. Once your music library and routines live in one place, switching feels costly—socially and emotionally, not just financially.

For Spotify, free also increases demand on the other side of the market: labels and artists want distribution where listeners already are. A bigger audience makes licensing negotiations and creator interest easier over time.

Ads + subscriptions without confusing users

The key is clarity: free is “good enough” but interrupted; premium is “your music, on your terms.” Spotify kept the core promise consistent—access to a massive catalog—while letting ads be the tradeoff for not paying.

That separation reduces resentment. Users don’t feel tricked; they feel in control of the deal: either pay with attention (ads) or pay with money (subscription).

Feature gating and pricing that nudges (without breaking)

Spotify’s conversion levers are mostly about removing friction for people who already listen a lot:

- Offline listening and downloadable playlists: critical for commuters and travelers.

- Skip limits / on-demand controls: free stays usable, but power users hit ceilings.

- Audio quality tiers: a simple upgrade story for enthusiasts.

Then pricing packages make “yes” easier for different budgets:

- Student plans lower the barrier for younger listeners.

- Family plans reduce per-person cost and lock in households.

The risks: margins, churn, and licensing dependence

Freemium can be expensive. Free users generate costs (streaming, royalties, product) while ad revenue can be volatile. On the premium side, churn spikes if people feel they’re not using it enough—or if competitors undercut pricing.

Most importantly, margins are constrained by licensing: as listening grows, royalty obligations grow too. That’s why Spotify’s freemium engine has to do two jobs at once—grow the funnel and improve retention—so the paid tier stays large enough to support the catalog it relies on.

Licensing 101: The Deal Structure Behind the App

Spotify doesn’t “sell music” so much as it rents access to rights. That’s why licensing isn’t a back-office detail—it’s the core contract that makes the product possible and largely determines what each stream costs.

What music licensing actually covers

There are two big buckets of rights:

- Sound recordings (the “master”): usually owned by record labels (or independent artists). This is the specific recorded track you hear.

- Publishing (the “composition”): owned by songwriters and publishers. This covers the underlying song—melody and lyrics—regardless of who records it.

A single play can trigger payments to both sides. That split is why a “complete catalog” is hard: you need clearance across multiple rights holders, sometimes with different rules by country.

Why licensing is central to streaming unit economics

Streaming revenue is typically shared with rights holders based on usage and agreements. Unlike selling a $1 download with a clear margin, streaming has ongoing variable cost per listen. If revenue per user (from subscriptions and ads) doesn’t outpace licensing obligations, growth can increase scale while keeping margins thin.

This is also why Spotify cares so much about retention: the longer a user stays, the more likely their monthly subscription covers the cost of their listening behavior.

What gets negotiated

Major deals tend to focus on:

- Territory and global rights: can Spotify offer the same album everywhere, or is it geo-limited?

- Windows and exclusivity: are new releases delayed, limited, or given special terms?

- Minimum guarantees and advances: upfront commitments that reduce rights-holder risk but raise Spotify’s fixed costs.

- Reporting and auditability: detailed play counts, territory splits, and payout calculations—trust is part of the product.

How licensing complexity shapes the product

Licensing constraints ripple into UX and expansion. They influence where Spotify can launch, which features are viable (offline playback, previews, DJ mixes, lyrics, user-generated content), and even how “available” music appears when a track is removed or restricted. Product strategy and market entry aren’t just engineering decisions—they’re negotiation outcomes made visible in the app.

Royalties, Stakeholders, and Incentives to Keep the Catalog

Iterate Without Fear

Experiment with pricing and UX changes, then roll back if the result is worse.

Spotify’s entire value proposition depends on having the songs people want. That means aligning incentives across a crowded chain of stakeholders—not just “artists vs. Spotify,” but a web of contracts, reporting, and expectations.

Who needs to feel treated fairly?

At a minimum, royalties touch:

- Listeners, who expect a deep catalog and reliable availability

- Advertisers, who fund free listening and want brand-safe reach

- Labels (recordings) and publishers (songwriting), who negotiate licenses and police usage

- Artists and songwriters, whose income and career momentum are affected by payouts and discovery

- Collecting societies, who administer certain rights and require accurate usage data

If any major group believes the economics don’t work, the risk isn’t theoretical: catalog gaps, delayed releases, or harder negotiations can directly degrade the product.

Transparency: the debate (without picking a side)

The transparency discussion tends to split into two valid concerns:

- Rights holders want clear, auditable reporting so they can verify money flows and detect mismatches.

- Platforms and some partners point to contract complexity and confidentiality, arguing that simplified public narratives can mislead.

You don’t have to “side” with either view to see the product risk: confusion erodes trust, and low trust makes renewals harder.

Why payout models and reporting detail matter

Even when total payouts grow, how they’re calculated affects perceived fairness. Differences between pro-rata vs. alternative models, the handling of promotions, and the granularity of play-level reporting all influence whether creators feel confident they’re being paid correctly.

Creator tools that reduce friction

Keeping the catalog isn’t only about checks—it’s about lowering operational pain. Creator-facing tools can help by:

- Improving credits and metadata (so the right people get paid)

- Offering analytics that explain performance and audience

- Enabling pitching and editorial workflows that feel predictable and accessible

When creators and rights holders can see what’s happening and act on it, the relationship shifts from suspicion to collaboration—making the catalog more stable over time.

Personalization as Product Strategy (Not Just an Algorithm)

Personalization at Spotify isn’t a nice-to-have feature—it’s a retention strategy. When an app can consistently find the “right next song,” it saves listeners time, reduces decision fatigue, and turns casual listening into a habit. The emotional payoff matters too: feeling understood keeps people coming back, even when competitors offer similar catalogs.

What Spotify “Listens” to (in plain language)

Spotify’s personalization starts with simple behavioral signals. Your listening history (what you play), your skips (what you reject), and your repeats (what you love) create a practical map of taste. Add context signals—time of day, device type, and how long you listen in a session—and the product can make educated guesses about what you want right now (focus music vs. party music vs. comfort favorites).

None of this requires users to set preferences in a complicated way. The product learns passively, which lowers friction and makes personalization feel effortless.

What you get: outputs that drive habit

The most visible outputs are:

- Personalized mixes (built around familiar patterns)

- Discovery playlists (designed for novelty with guardrails)

- Radio stations (one seed track turned into a continuous session)

- Home screen recommendations (fast, low-effort starting points)

These surfaces aren’t just algorithm showcases—they’re product shortcuts that help users press play within seconds.

The trade-offs: avoiding sameness without losing comfort

Personalization can backfire if it creates repetition, “samey” recommendations, or a filter bubble that hides new and long-tail artists. The product challenge is balancing two competing feelings: the comfort of familiarity and the excitement of discovery. Spotify’s best personalization doesn’t only predict what you’ll like—it deliberately schedules exploration so the experience stays fresh.

How Discovery Benefits Both Listeners and Creators

Make It Feel Real

Put your prototype on a custom domain to make feedback and sharing easier.

Discovery is where Spotify’s personalization connects directly to its two-sided market. Listeners want music that feels “made for me,” while artists want a fair shot at being heard. A recommendation system that reliably matches people to songs creates value on both sides at the same time: better listening experiences and more meaningful exposure.

Better matching reduces churn (and makes the catalog feel bigger)

When a listener quickly finds tracks that fit their mood, habits, and context, they’re less likely to leave. That lowers churn and improves retention—especially for people who started on the free tier and need a reason to keep returning.

Good discovery also changes how the catalog is perceived. Even if the library is already huge, it can feel overwhelming without guidance. Strong matching makes the catalog feel deeper because users actually encounter more of it: more genres, more eras, more niches. That perceived depth is a product advantage without adding a single new song.

Editorial + algorithmic curation: complementary, not competing

Spotify benefits from using both approaches together:

- Editorial playlists can set quality bars, cultural context, and seasonal programming.

- Algorithmic recommendations can personalize at scale, respond to behavior in near real time, and surface long-tail artists.

Editorial can also “train” listener trust: once a user believes playlists are consistently good, they’re more willing to try new recommendations.

How platforms evaluate recommendation quality

Discovery isn’t judged only by clicks. Teams typically track a mix of short-term and long-term signals, such as:

- Engagement (listening time, session frequency)

- Positive intent actions (saves/likes, playlist adds, follows)

- Exploration (new artists tried, depth of listening beyond one track)

- Long-term use (return rate, retention, reduced skips over time)

For creators, quality discovery means reaching listeners with genuine intent—people who save songs and come back—rather than one-off plays that don’t build a career.

Global Expansion: Localization, Partnerships, and Device Ubiquity

Spotify’s global growth wasn’t just “launch the app everywhere.” Music rights, payment habits, and device ecosystems differ dramatically by country, so scaling meant solving a new business problem each time—without breaking the product experience that made Spotify feel effortless.

Why global scale is hard

Streaming rights are typically negotiated per territory. A catalog that looks complete in one market can be missing major artists in another, and release windows can vary. Add language differences, local charts, and culturally specific listening moments, and “one global product” quickly becomes hundreds of local realities.

Payments create another layer of friction. Some countries lean on credit cards; others rely on mobile wallets, bank transfers, or prepaid options. If upgrading is hard, the freemium funnel stalls—even if listening is booming.

Localization that feels native

Spotify’s localization has often been practical rather than flashy:

- Regional catalogs that reflect what people actually search for (and what’s legally available)

- Curated local playlists that mirror radio-like habits and local genres

- Partnerships with carriers, retailers, and media companies that bundle Premium or simplify billing

This isn’t just marketing. It aligns listener demand with what labels and artists in that country want: predictable promotion and revenue.

Device ubiquity as distribution

Global adoption accelerates when listening is possible everywhere people already are: phones, cars, speakers, TVs, game consoles, and wearables. Integrations reduce the “app switching” cost and make Spotify a default audio layer—especially in cars and smart speakers, where voice and hands-free control matter.

Operational reality: support, compliance, consistency

With more markets comes more customer support, content policies, and regulatory requirements (privacy, payments, consumer rights). The challenge is keeping a consistent UX while honoring local rules and expectations—so the product still feels like Spotify, not a patchwork of regional versions.

From Music App to Audio Platform: Podcasts and Beyond

Spotify’s shift from “music streaming” to “audio platform” follows directly from platform logic. Once you’ve built a massive user base with predictable habits (open app, hit play, keep listening), you can serve more than one audio format through the same distribution engine: the same app, recommendations, payments, and ad stack. Music, podcasts, and audiobooks all compete for attention, but they can also reinforce each other by increasing total time spent and reducing churn.

Why add podcasts and audiobooks?

Podcasts and audiobooks change the business equation in three strategic ways.

First, engagement: spoken-word content can create longer sessions (commutes, workouts, chores) and daily rituals (news, recurring shows). More listening time improves retention and gives Spotify more opportunities to personalize the experience.

Second, differentiation: music catalogs are largely substitutable across services—most competitors license the same songs. Exclusive or original podcasts, creator-led shows, and curated audiobook offerings can make the product feel meaningfully different.

Third, margins: music carries ongoing royalty costs tied to consumption. Podcasts (especially owned or directly monetized) can offer more flexible economics—ads, subscriptions, sponsorships, or licensing that isn’t strictly per stream. Audiobooks can also be structured in ways that resemble retail, bundles, or credit-based access rather than unlimited streaming.

Licensing differences and risk

Music licensing is complex and recurring: the more users stream, the more Spotify pays rights holders. With podcasts, Spotify can license shows, host creators, or produce originals—often shifting cost from variable (per stream) to more predictable fixed deals. That can reduce certain risks while introducing others: content moderation, brand safety for ads, and the need to keep a pipeline of compelling exclusives.

Product implications: the battle for the home screen

A multi-format platform forces hard product choices. Home screen real estate becomes strategic: how much to feature music vs. podcasts vs. audiobooks—and for which users. Search and library organization must support different mental models: songs, albums, episodes, shows, and books don’t fit into one simple hierarchy.

Done well, this expands the “what should I listen to next?” moment beyond music—without making the app feel cluttered or confusing.

Competitive Pressure and Defensibility in Streaming

From Strategy to Shipping

Create a React web app with a Go backend and PostgreSQL from a simple spec.

Spotify doesn’t just compete with other music streamers. It competes with anything that can satisfy “I want something to listen to right now,” and that widens the battlefield.

The real competitive set

Music streaming rivals (Apple Music, Amazon Music, YouTube Music) fight on catalog breadth, pricing, and device bundling. But Spotify also competes with:

- Video platforms (especially YouTube and TikTok), where music discovery happens before listening happens

- Radio and satellite for passive, “don’t make me choose” listening

- Short-form apps that win attention minutes—even when they don’t monetize music directly

The practical implication: the core scarcity isn’t songs, it’s time, habit, and default placement.

What a “moat” can realistically mean

In streaming, a moat is rarely a locked gate. It’s more like a set of advantages that make switching slightly annoying and staying slightly better:

- Brand + trust: “I’ll find what I want here” (and it will work)

- Personalization: playlists and recommendations that feel uniquely “mine,” built from years of signals

- Distribution: being integrated with cars, speakers, consoles, and telco bundles

- Data loop: more listening creates better suggestions, which creates more listening

None of these remove competitors—but together they can raise the cost of replacing Spotify as someone’s default audio app.

Key risks to defensibility

Spotify’s power is constrained by structural pressures:

- Licensing dependency: rights holders can renegotiate economics and leverage.

- Price competition: subscriptions look similar, making bundling and discounts potent weapons.

- Creator dissatisfaction: if artists and publishers feel underpaid or under-supported, the platform’s long-term narrative weakens.

Thinking about resilience (without predictions)

A resilient platform is one that can absorb shocks: changes in label terms, new formats, or new attention competitors. For Spotify, that means diversifying listening use cases (music, podcasts, audiobooks), strengthening creator tools, and expanding distribution so the app stays the easiest place to press play.

Practical Takeaways for Product and Business Builders

Spotify’s story under Daniel Ek boils down to repeatable lessons that apply to most platforms—whether you’re building a marketplace, a media product, or a creator ecosystem.

Three core lessons to borrow

1) Balance the marketplace, not just the customer. Growth that looks great on the demand side can still fail if suppliers (labels, creators, distributors) feel squeezed or ignored.

2) Treat licensing (or supply contracts) as a product constraint. Deal terms define your catalog, margins, user experience, and even your roadmap. If supply is governed by rights, compliance, or inventory rules, you don’t “figure it out later”—you design around it.

3) Make personalization a strategy, not a feature. Recommendations aren’t only about engagement. They reduce choice paralysis, improve perceived value, and create a retention loop that’s hard to copy without comparable data and usage signals.

A practical platform checklist

- Pricing: What are you subsidizing (free tier, discounts, incentives), and what’s the planned path to sustainable unit economics?

- Supply acquisition: Who needs to say “yes” first, and what do they fear (cannibalization, fraud, opaque reporting)? Address that early.

- Retention loops: What habits will exist in 30 days—playlists, follows, saved items, recurring use cases?

- Onboarding: Can a new user reach “this is for me” in under 2 minutes?

- Measurement: Track both sides: demand retention and supply satisfaction (payout clarity, analytics, issue resolution time).

Common pitfalls to avoid

- Over-subsidizing demand without a credible plan to improve margins or conversion.

- Ignoring supply-side trust: unclear reporting, slow payments, or weak enforcement creates churn on the catalog/creator side.

- Weak onboarding: if personalization takes too long to become relevant, users leave before the flywheel starts.

One practical way to apply these lessons outside music is to prototype your own “platform flywheel” early—then test it with real users. For example, teams using Koder.ai (a vibe-coding platform that builds web, backend, and mobile apps from chat) often start by shipping a thin but complete product loop—onboarding, pricing tiers, and retention hooks—before investing heavily in custom engineering. That makes it easier to validate whether your two-sided dynamics, personalization surfaces, or monetization gates actually work in practice.

For more on these patterns, see /blog/platform-strategy. If you’re refining monetization, /pricing can help frame packaging and conversion choices.

FAQ

What does it mean to say Spotify is a platform, not just a music streaming app?

Spotify is best understood as a platform coordinating multiple stakeholders:

- Listeners (demand)

- Rights holders (labels, publishers, and creators) who control the catalog (supply)

- Advertisers (funding free listening)

- Device and distribution partners (cars, speakers, telcos)

That platform structure—more than any single feature—drives the key trade-offs around growth, royalties, and retention.

How does the two-sided market dynamic shape Spotify’s strategy?

In a two-sided market, the product must work for both listeners and rights holders at the same time.

- Listeners want instant access, a complete-feeling catalog, and low friction.

- Rights holders want reach, revenue, and credible discovery.

If either side feels shortchanged, the “catalog quality” or release support can degrade, which then harms the listener experience.

Why is music licensing central to Spotify’s product and economics?

Because streaming is access to licensed rights, not ownership.

A “complete catalog” requires clearance across two major rights buckets:

- Sound recordings (masters) (often labels/independent artists)

- Publishing (compositions) (songwriters/publishers)

Deal terms affect what can ship (offline, previews, lyrics/UGC), where Spotify can launch, and how costly each additional stream is.

How does Spotify’s freemium model help it grow without confusing users?

Freemium is a habit-building engine:

- Free tier lowers friction so users can build playlists, follows, and routines.

- Premium then monetizes the heaviest listeners who value control and convenience.

Conversion is usually driven by removing pain points for power users (offline downloads, fewer limits, better controls) rather than making free unusable.

What are the biggest risks and trade-offs in Spotify’s unit economics?

Streaming has ongoing variable costs tied to listening (royalties and delivery). That creates a few practical constraints:

- Rapid growth can keep margins thin if revenue per user doesn’t outpace per-user listening cost.

- Retention matters because a stable monthly subscription is easier to “cover” heavy usage over time.

- The supply side (rights holders) can renegotiate terms, affecting unit economics.

So “scale” only helps if it also improves retention and negotiating position.

If users can switch easily, what creates real switching costs for Spotify?

They show up through accumulated user investment:

- Playlists and saved library (time invested)

- Personalized recommendations (the system has learned you)

- Offline routines (habits that fit your life)

Most users also (Spotify + YouTube/Apple/etc.), so the goal is often to become the service, not the only one.

How does personalization actually improve retention and reduce churn?

Personalization is a retention strategy, not just an algorithm:

- It reduces decision fatigue (“what should I play?”).

- It increases perceived catalog value by surfacing the right subset fast.

- It creates a data loop: more listening → better recommendations → more listening.

In practice, winning is often about getting users to “press play in seconds” via mixes, discovery playlists, radio, and a strong home screen.

How does Spotify’s discovery system create value for both listeners and creators?

Good discovery benefits both sides:

- Listeners get better matching (mood, context), which reduces churn.

- Creators get exposure to listeners with real intent (saves, follows, repeat listening), not just one-off plays.

Many platforms blend:

- Editorial curation (quality/context)

- Algorithmic recommendations (personalization at scale)

Quality is typically measured beyond clicks: saves, playlist adds, return rate, skip rates, and long-term retention.

Why is global expansion in streaming so operationally complex?

Global scale requires solving local constraints without breaking the core experience:

- Rights are often negotiated per territory, so catalogs and release windows can vary.

- Payments differ by country, so upgrading may require local methods (bundles, prepaid, carrier billing).

- Localization is often practical: regional playlists, local charts, and partnerships.

Device ubiquity (cars, speakers, consoles) also matters because it reduces app-switching friction and increases daily minutes.

What does defensibility look like for Spotify versus competitors?

Music catalogs are broadly substitutable across streamers, so differentiation often comes from:

- Personalization that feels uniquely “yours”

- Distribution (cars/speakers/telco bundles)

- Product trust and reliability

- Expanding formats (podcasts/audiobooks) to increase time spent and diversify economics

A “moat” is usually a bundle of small advantages. For a platform-builder checklist, see /blog/platform-strategy; for packaging and conversion framing, see /pricing.