Oct 03, 2025·7 min

Data on the Outside vs Inside - Pat Helland Lessons for Apps

Learn Pat Helland's data on the outside vs inside to set clear boundaries, design idempotent calls, and reconcile state when networks fail.

What “outside vs inside” means in plain language

When you build an app, it’s easy to picture requests arriving neatly, one by one, in the right order. Real networks don’t behave like that. A user taps “Pay” twice because the screen froze. A mobile connection drops right after a button press. A webhook arrives late, or arrives twice. Sometimes it never arrives at all.

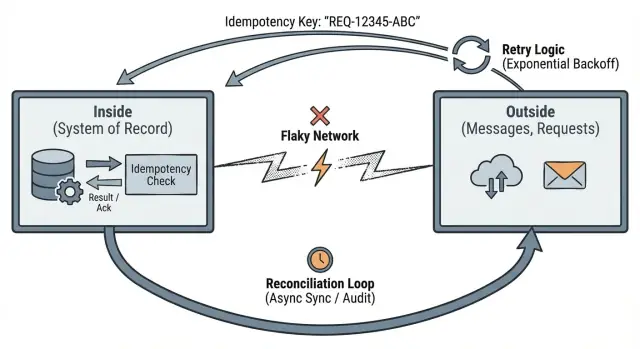

Pat Helland’s idea of data on the outside vs inside is a clean way to think about that mess.

What “outside” looks like

“Outside” is everything your system doesn’t control. It’s where you talk to other people and systems, and where delivery is uncertain: HTTP requests from browsers and mobile apps, messages from queues, third-party webhooks (payments, email, shipping), and retries triggered by clients, proxies, or background jobs.

On the outside, assume messages can be delayed, duplicated, or arrive out of order. Even if something is “usually reliable,” design for the day it isn’t.

What “inside” means

“Inside” is what your system can make dependable. It’s the durable state you store, the rules you enforce, and the facts you can prove later:

- Database records and their history

- Business rules (for example: “an order can only be paid once”)

- A source of truth for status (pending, paid, canceled)

Inside is where you protect invariants. If you promise “one payment per order,” that promise must be enforced inside, because the outside can’t be trusted to behave.

The mindset shift is simple: don’t assume perfect delivery or perfect timing. Treat every outside interaction as an unreliable suggestion that might be repeated, and make the inside react safely.

This matters even for small teams and simple apps. The first time a network glitch creates a duplicate charge or a stuck order, it stops being theory and becomes a refund, a support ticket, and a loss of trust.

A concrete example: a user hits “Place order,” the app sends a request, and the connection drops. The user tries again. If your inside has no way to recognize “this is the same attempt,” you might create two orders, reserve inventory twice, or email two confirmations.

The key lesson from Pat Helland

Helland’s point is straightforward: the outside world is uncertain, but the inside of your system must stay consistent. Networks drop packets, phones lose signal, clocks drift, and users hit refresh. Your app can’t control any of that. What it can control is what it accepts as “true” once data crosses a clear boundary.

Time and uncertainty in one everyday moment

Picture someone ordering coffee on their phone while walking through a building with bad Wi‑Fi. They tap “Pay.” The spinner turns. The network cuts out. They tap again.

Maybe the first request reached your server, but the response never made it back. Or maybe neither request arrived. From the user’s view, both possibilities look the same.

That’s time and uncertainty: you don’t know what happened yet, and you might learn later. Your system needs to behave sensibly while it waits.

Retries, duplicates, and reordering

Once you accept that the outside is unreliable, a few “weird” behaviors become normal:

- Retries create duplicates (two “Pay” requests).

- Messages arrive out of order (a “cancel” arrives before “pay”).

- A request is processed, but the client never sees the response.

Outside data is a claim, not a fact. “I paid” is just a statement sent over an unreliable channel. It becomes a fact only after you record it inside your system in a durable, consistent way.

This pushes you toward three practical habits: define clear boundaries, make retries safe with idempotency, and plan for reconciliation when reality doesn’t line up.

Clear boundaries: what your system owns and what it does not

The “outside vs inside” idea starts with a practical question: where does your system’s truth begin and end?

Inside the boundary, you can make strong guarantees because you control the data and the rules. Outside the boundary, you make best-effort attempts and assume messages can be lost, duplicated, delayed, or arrive out of order.

In real apps, that boundary often appears at places like:

- An API endpoint that writes a record to your database

- A queue consumer that turns an event into a stored change

- A callback handler that records what a provider says happened

- A sender that notifies another system after you commit your own state

Once you draw that line, decide which invariants are non-negotiable inside it. Examples:

- An order ID is unique in your database.

- A balance never goes negative.

- A state only moves forward (created -> paid -> shipped).

- Every external request you accept has a stored audit trail.

The boundary also needs clear language for “where we are.” A lot of failures live in the gap between “we heard you” and “we finished it.” A helpful pattern is to separate three meanings:

- Received: the message arrived at your edge (not necessarily saved yet)

- Accepted: you saved it and can safely retry work later

- Processed: the intended work completed and you recorded the outcome

When teams skip this, they end up with bugs that only happen under load or during partial outages. One system uses “paid” to mean money captured; another uses it to mean a payment attempt started. That mismatch creates duplicates, stuck orders, and support tickets nobody can reproduce.

Idempotency: making retries safe

Idempotency means: if the same request is sent twice, the system treats it like one request and returns the same outcome.

Retries are normal. Timeouts happen. Clients repeat themselves. If the outside can repeat, your inside has to turn that into stable state changes.

A simple example: a mobile app sends “pay $20” and the connection drops. The app retries. Without idempotency, the customer might be charged twice. With idempotency, the second request returns the first charge result.

Common ways to implement idempotency

Most teams use one of these patterns (sometimes a mix):

- Idempotency key: the client sends a unique key per intended action (for example,

Idempotency-Key: ...). The server records the key and the final response. - De-duplication table: store a row keyed by (client_id, key) or (order_id, operation) and refuse a second side effect.

- Natural keys: use a business identifier that is already unique, so “create payment” can only exist once.

When a duplicate arrives, the best behavior usually isn’t “409 conflict” or a generic error. It’s returning the same result you returned the first time, including the same resource ID and status. That’s what makes retries safe for clients and background jobs.

Where to keep the record (and for how long)

The idempotency record must live inside your boundary in durable storage, not in memory. If your API restarts and forgets, the safety guarantee disappears.

Keep records long enough to cover realistic retries and delayed deliveries. The window depends on business risk: minutes to hours for low-risk creates, days for payments/emails/shipments where duplicates are costly, and longer if partners can retry for extended periods.

How to avoid “distributed transaction” traps

Earn credits for sharing builds

Create content or refer others to Koder.ai and earn credits as you build.

Distributed transactions sound comforting: one big commit across services, queues, and databases. In practice they’re often unavailable, slow, or too fragile to depend on. Once a network hop is involved, you can’t assume everything commits together.

A common trap is building a workflow that only works if every step succeeds right now: save order, charge card, reserve inventory, send confirmation. If step 3 times out, did it fail or succeed? If you retry, will you double-charge or double-reserve?

Two practical approaches avoid this:

- Outbox/inbox: write a durable intent inside your database (an outbox row) in the same transaction as your state change, then have a worker send the message. On the receiving side, keep an inbox keyed by message ID so handling is safe if the same message arrives again.

- Saga-style steps with compensations: break the workflow into smaller steps that complete independently. If a later step fails, run a compensation (for example, release inventory or cancel an unpaid order) instead of trying to roll back history.

Pick one style per workflow and stick with it. Mixing “sometimes we do an outbox” with “sometimes we assume synchronous success” creates edge cases that are hard to test.

A simple rule helps: if you can’t atomically commit across boundaries, design for retries, duplicates, and delays.

Reconciliation: how real systems recover from mismatches

Reconciliation is admitting a basic truth: when your app talks to other systems over a network, you will sometimes disagree about what happened. Requests time out, callbacks arrive late, and people retry actions. Reconciliation is how you detect mismatches and fix them over time.

Treat outside systems as independent sources of truth. Your app keeps its own internal record, but it needs a way to compare that record with what partners, providers, and users actually did.

Common reconciliation mechanisms

Most teams use a small set of boring tools (boring is good): a worker that retries pending actions and re-checks external status, a scheduled scan for inconsistencies, and a small admin repair action for support to retry, cancel, or mark as reviewed.

What to compare and what to record

Reconciliation only works if you know what to compare: internal ledger vs provider ledger (payments), order state vs shipment state (fulfillment), subscription state vs billing state.

Make states repairable. Instead of jumping straight from “created” to “completed,” use holding states like pending, on hold, or needs review. That makes it safe to say “we’re not sure yet,” and it gives reconciliation a clear place to land.

Capture a small audit trail on important changes:

- When you sent a request and when you last heard back

- Correlation IDs that tie your record to an external event/reference

- The last known external status (and where it came from)

- A reason field for manual overrides (who, what, why)

Example: if your app requests a shipment label and the network drops, you might end up with “no label” internally while the carrier actually created one. A recon worker can search by correlation ID, discover the label exists, and move the order forward (or mark it for review if details don’t match).

Step by step: designing a workflow that survives network failure

Make mobile retries predictable

Create a Flutter client that retries safely with stable request IDs.

Once you assume the network will fail, the goal changes. You’re not trying to make every step succeed in one try. You’re trying to make every step safe to repeat and easy to repair.

A practical workflow

-

Write a one-sentence boundary statement. Be explicit about what your system owns (the source of truth), what it mirrors, and what it only requests from others.

-

List failure modes before the happy path. At minimum: timeouts (you don’t know if it worked), duplicate requests, partial success (one step happened, the next didn’t), and out-of-order events.

-

Choose an idempotency strategy for each input. For synchronous APIs, that’s often an idempotency key plus a stored result. For messages/events, it’s usually a unique message ID and a “have I processed this?” record.

-

Persist intent, then act. First store something durable like “PaymentAttempt: pending” or “ShipmentRequest: queued,” then do the external call, then store the outcome. Return a stable reference ID so retries point at the same intent instead of creating a new one.

-

Build reconciliation and a repair path, and make them visible. Reconciliation can be a job that scans “pending too long” records and re-checks status. The repair path can be a safe admin action like “retry,” “cancel,” or “mark resolved,” with an audit note. Add basic observability: correlation IDs, clear status fields, and a few counts (pending, retries, failures).

Example: if checkout times out right after you call a payment provider, don’t guess. Store the attempt, return the attempt ID, and let the user retry with the same idempotency key. Later, reconciliation can confirm whether the provider charged or not and update the attempt without double-charging.

Example scenario: an order flow with retries and delayed callbacks

A customer taps “Place order.” Your service sends a payment request to a provider, but the network is flaky. The provider has its own truth, and your database has yours. They will drift unless you design for it.

What happens on the outside (events you do not control)

From your point of view, the outside is a stream of messages that can be late, repeated, or missing:

- “Submit order” hits your API.

- Your payment request goes to the provider.

- The provider sends a webhook saying “authorized.”

- The provider retries the webhook and sends the same callback again.

- Your client times out and retries “Place order.”

None of those steps guarantee “exactly once.” They only guarantee “maybe.”

What you keep on the inside (records you do control)

Inside your boundary, store durable facts and the minimum needed to connect outside events to those facts.

When the customer first places the order, create an order record in a clear state like pending_payment. Also create a payment_attempt record with a unique provider reference plus an idempotency_key tied to the customer action.

If the client times out and retries, your API shouldn’t create a second order. It should look up the idempotency_key and return the same order_id and current state. That one choice prevents duplicates when networks fail.

Now the webhook arrives twice. The first callback updates payment_attempt to authorized and moves the order to paid. The second callback hits the same handler, but you detect you already processed that provider event (by storing the provider event ID, or by checking current state) and do nothing. You can still respond 200 OK, because the result is already true.

Finally, reconciliation handles the messy cases. If the order is still pending_payment after a delay, a background job queries the provider using the stored reference. If the provider says “authorized” but you missed the webhook, you update your records. If the provider says “failed” but you marked it paid, you flag it for review or trigger a compensating action like a refund.

Common mistakes that cause duplicates and stuck states

Go from idea to deployment

Build, deploy, and host your app from the same chat-driven workspace.

Most duplicate records and “stuck” workflows come from mixing up what happened outside your system (a request arrived, a message was received) with what you safely committed inside your system.

A classic failure: a client sends “place order,” your server starts work, the network drops, and the client retries. If you treat each retry as brand-new truth, you get double charges, duplicate orders, or multiple emails.

The usual causes are:

- Trusting the incoming request too early: sending emails or logging “order created” before the database commit is durable.

- Retries that create new rows: generating a new order ID on every attempt instead of mapping retries to one outcome.

- Assuming “exactly once” delivery: queues and callbacks don’t promise that. Duplicates, delays, and reordering happen.

- No stable identifiers: if you can’t answer “have I seen this exact intent before?”, you can’t prevent duplicates.

- Only success/failure, no middle state: without pending/awaiting states, timeouts become mysteries and users click again.

One issue makes everything worse: no audit trail. If you overwrite fields and keep only the latest state, you lose the evidence you need to reconcile later.

A good sanity check is: “If I run this handler twice, do I get the same result?” If the answer is no, duplicates aren’t a rare edge case. They’re guaranteed.

A quick checklist and practical next steps

If you remember one thing: your app must stay correct even when messages arrive late, arrive twice, or never arrive at all.

Use this checklist to spot weak points before they turn into duplicate records, missing updates, or stuck workflows:

- Source of truth is explicit: for each workflow, you can point to one place that is “the truth” (often your database).

- Every write can be retried safely: each command/API call has an idempotency key (or a natural unique key).

- Stable IDs and correlation IDs exist end to end: you can trace one business action across logs, tables, and callbacks.

- Reconciliation runs automatically: you regularly compare “what we believe” vs “what happened” and repair or raise a clear alert.

- Rollback doesn’t corrupt state: state changes are auditable and compatible across versions.

If you can’t answer one of these quickly, that’s useful. It usually means a boundary is fuzzy or a state transition is missing.

Practical next steps:

-

Sketch boundaries and states first. Define a small set of states per workflow (for example: Created, PaymentPending, Paid, FulfillmentPending, Completed, Failed).

-

Add idempotency where it matters most. Start with the highest-risk writes: create order, capture payment, issue refund. Store idempotency keys in PostgreSQL with a unique constraint so duplicates are rejected safely.

-

Treat reconciliation as a normal feature. Schedule a job that searches for “pending too long” records, checks external systems again, and repairs local state.

-

Iterate safely. Adjust transitions and retry rules, then test by deliberately re-sending the same request and re-processing the same event.

If you’re building quickly on a chat-driven platform like Koder.ai (koder.ai), it’s still worth baking these rules into your generated services early: the speed comes from automation, but the reliability comes from clear boundaries, idempotent handlers, and reconciliation.

FAQ

What does “data on the outside vs inside” mean in simple terms?

“Outside” is anything you don’t control: browsers, mobile networks, queues, third‑party webhooks, retries, and timeouts. Assume messages can be delayed, duplicated, lost, or arrive out of order.

“Inside” is what you do control: your stored state, your rules, and the facts you can prove later (usually in your database).

Why can’t I trust incoming requests or webhooks to happen exactly once?

Because the network lies to you.

A client timing out doesn’t mean your server didn’t process the request. A webhook arriving twice doesn’t mean the provider did the action twice. If you treat every message as “new truth,” you’ll create duplicate orders, double charges, and stuck workflows.

Where should I draw the “boundary” in a typical app?

A clear boundary is the point where an unreliable message becomes a durable fact.

Common boundaries are:

- An API endpoint that commits to your database

- A queue consumer that stores an event as a state change

- A webhook handler that records what the provider claims happened

Once the data crosses the boundary, you enforce invariants inside (like “order can be paid once”).

How do I stop double charges when users retry “Pay”?

Use idempotency. The default is: the same intent should produce the same result even if sent multiple times.

Practical patterns:

- Client sends an idempotency key per action

- Server stores the key and the final result in durable storage

- On duplicates, return the same resource ID/status as the first request

Where do I store idempotency records, and how long should I keep them?

Don’t keep it only in memory. Store it inside your boundary (for example, PostgreSQL) so restarts don’t erase your protection.

Retention rule of thumb:

- Low-risk actions: minutes to hours

- High-cost actions (payments, refunds, shipments, emails): days or longer

Keep it long enough to cover realistic retries and delayed callbacks.

What states should I add to avoid “we’re not sure” bugs?

Use states that admit uncertainty.

A simple, practical set:

pending_*(we accepted the intent but don’t know the outcome yet)succeeded/failed(we recorded a final outcome)needs_review(we detected a mismatch that requires a human or a special job)

Why are distributed transactions usually a trap for app workflows?

Because you can’t atomically commit across multiple systems over a network.

If you do “save order → charge card → reserve inventory” synchronously and step 2 times out, you won’t know whether to retry. Retrying can cause duplicates; not retrying can leave work unfinished.

Design for partial success: persist intent first, then perform external actions, then record outcomes.

What is the outbox/inbox pattern, and when should I use it?

The outbox/inbox pattern makes cross-system messaging reliable without pretending the network is perfect.

- Outbox: in the same database transaction as your state change, write a row that represents the message you intend to send.

- A worker reads the outbox and sends the message.

- Inbox (receiver side): store processed message IDs so re-deliveries don’t create duplicate side effects.

What is reconciliation, and what’s a simple way to implement it?

Reconciliation is how you recover when your records and an external system disagree.

Good defaults:

- A scheduled job that re-checks “pending too long” items

- A comparison step (your state vs provider state)

- A repair action: retry, cancel, refund, or mark

needs_review

It’s not optional for payments, fulfillment, subscriptions, or anything with webhooks.

Does this still matter if I’m building quickly with a platform like Koder.ai?

Yes. Fast building doesn’t remove network failure—it just gets you to it sooner.

If you’re generating services with Koder.ai, bake in these defaults early:

- Clear boundary (when an intent becomes durable)

- Idempotent handlers for “create/capture/refund”-style actions

- Correlation IDs stored with external references

- A reconciliation job for pending records

That way, retries and duplicate callbacks become boring instead of expensive.