Sep 15, 2025·8 min

David Patterson, RISC Thinking, and Co-Design’s Lasting Impact

Explore how David Patterson’s RISC thinking and hardware-software co-design improved performance per watt, shaped CPUs, and influenced RISC-V today.

Explore how David Patterson’s RISC thinking and hardware-software co-design improved performance per watt, shaped CPUs, and influenced RISC-V today.

David Patterson is often introduced as “a RISC pioneer,” but his lasting influence is broader than any single CPU design. He helped popularize a practical way of thinking about computers: treat performance as something you can measure, simplify, and improve end-to-end—from the instructions a chip understands to the software tools that generate those instructions.

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing) is the idea that a processor can run faster and more predictably when it focuses on a smaller set of simple instructions. Instead of building a huge menu of complicated operations in hardware, you make the common operations quick, regular, and easy to pipeline. The payoff isn’t “less capability”—it’s that simple building blocks, executed efficiently, often win in real workloads.

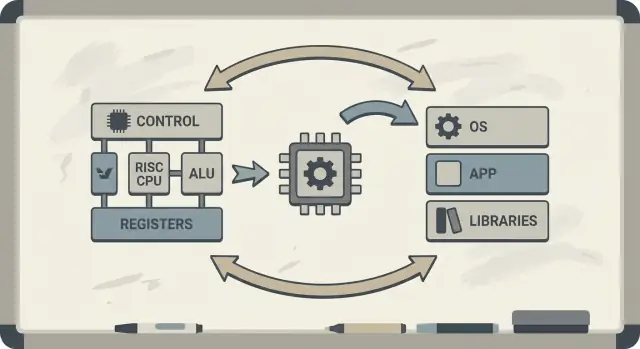

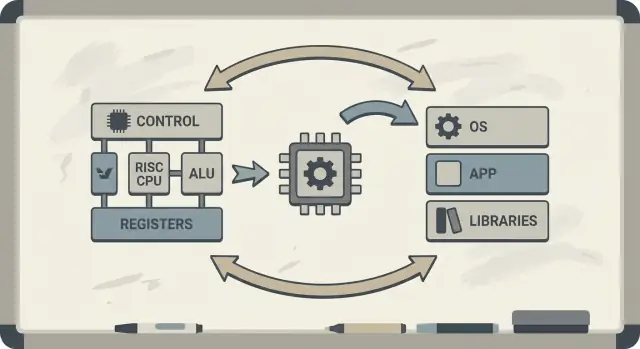

Patterson also championed hardware–software co-design: a feedback loop where chip architects, compiler writers, and system designers iterate together.

If a processor is designed to execute simple patterns well, compilers can reliably produce those patterns. If compilers reveal that real programs spend time in certain operations (like memory access), hardware can be adjusted to handle those cases better. This is why discussions about an instruction set architecture (ISA) naturally connect to compiler optimizations, caching, and pipelining.

You’ll learn why RISC ideas connect to performance per watt (not just raw speed), how “predictability” makes modern CPUs and mobile chips more efficient, and how these principles show up in today’s devices—from laptops to cloud servers.

If you want a map of the key concepts before diving deeper, skip ahead to /blog/key-takeaways-and-next-steps.

Early microprocessors were built under tight constraints: chips had limited room for circuitry, memory was expensive, and storage was slow. Designers were trying to ship computers that were affordable and “fast enough,” often with small caches (or none), modest clock speeds, and very limited main memory compared with what software wanted.

A popular idea at the time was that if the CPU offered more powerful, high-level instructions—ones that could do multiple steps at once—programs would run faster and be easier to write. If one instruction could “do the work of several,” the thinking went, you’d need fewer instructions overall, saving time and memory.

That’s the intuition behind many CISC (complex instruction set computing) designs: give programmers and compilers a big toolbox of fancy operations.

The catch was that real programs (and the compilers translating them) didn’t consistently take advantage of that complexity. Many of the most elaborate instructions were rarely used, while a small set of simple operations—load data, store data, add, compare, branch—showed up again and again.

Meanwhile, supporting a huge menu of complex instructions made CPUs harder to build and slower to optimize. Complexity consumed chip area and design effort that could have gone toward making the common, everyday operations run predictably and quickly.

RISC was a response to that gap: focus the CPU on what software truly does most of the time, and make those paths fast—then let compilers do more of the “orchestration” work in a systematic way.

A simple way to think about CISC vs RISC is to compare toolkits.

CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computing) is like a workshop filled with many specialized, fancy tools—each can do a lot in one move. A single “instruction” might load data from memory, do a calculation, and store the result, all bundled together.

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing) is like carrying a smaller set of reliable tools you use constantly—hammer, screwdriver, measuring tape—and building everything from repeatable steps. Each instruction tends to do one small, clear job.

When instructions are simpler and more uniform, the CPU can execute them with a cleaner assembly line (a pipeline). That assembly line is easier to design, easier to run at higher clock speeds, and easier to keep busy.

With CISC-style “do-a-lot” instructions, the CPU often has to decode and break a complex instruction into smaller internal steps anyway. That can add complexity and make it harder to keep the pipeline flowing smoothly.

RISC aims for predictable instruction timing—many instructions take about the same amount of time. Predictability helps the CPU schedule work efficiently and helps compilers generate code that keeps the pipeline fed instead of stalling.

RISC usually needs more instructions to do the same task. That can mean:

But that can still be a good deal if each instruction is fast, the pipeline stays smooth, and the overall design is simpler.

In practice, well-optimized compilers and good caching can offset the “more instructions” downside—and the CPU can spend more time doing useful work and less time untangling complicated instructions.

Berkeley RISC wasn’t just a new instruction set. It was a research attitude: don’t start with what seems elegant on paper—start with what programs actually do, then shape the CPU around that reality.

At a conceptual level, the Berkeley team aimed for a CPU core that was simple enough to run very quickly and predictably. Instead of packing the hardware with many complicated instruction “tricks,” they leaned on the compiler to do more of the work: choose straightforward instructions, schedule them well, and keep data in registers as much as possible.

That division of labor mattered. A smaller, cleaner core is easier to pipeline effectively, easier to reason about, and often faster per transistor. The compiler, seeing the whole program, can plan ahead in ways hardware can’t easily do on the fly.

David Patterson emphasized measurement because computer design is full of tempting myths—features that sound useful but rarely show up in real code. Berkeley RISC pushed for using benchmarks and workload traces to find the hot paths: the loops, function calls, and memory accesses that dominate runtime.

This ties directly to the “make the common case fast” principle. If most instructions are simple operations and loads/stores, then optimizing those frequent cases pays off more than accelerating rare, complex instructions.

The lasting takeaway is that RISC was both an architecture and a mindset: simplify what’s frequent, validate with data, and treat hardware and software as a single system that can be tuned together.

Hardware–software co-design is the idea that you don’t design a CPU in isolation. You design the chip and the compiler (and sometimes the operating system) with each other in mind, so that real programs run fast and efficiently—not just synthetic “best case” instruction sequences.

Co-design works like an engineering loop:

ISA choices: the instruction set architecture (ISA) decides what the CPU can express easily (for example, “load/store” memory access, lots of registers, simple addressing modes).

Compiler strategies: the compiler adapts—keeping hot variables in registers, reordering instructions to avoid stalls, and choosing calling conventions that reduce overhead.

Workload results: you measure real programs (compilers, databases, graphics, OS code) and see where time and energy go.

Next design: you tweak the ISA and microarchitecture (pipeline depth, number of registers, cache sizes) based on those measurements.

Here’s a tiny loop (C) that highlights the relationship:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

sum += a[i];

On a RISC-style ISA, the compiler typically keeps sum and i in registers, uses simple load instructions for a[i], and performs instruction scheduling so the CPU stays busy while a load is in flight.

If a chip adds complex instructions or special hardware that compilers rarely use, that area still consumes power and design effort. Meanwhile, the “boring” things compilers do rely on—enough registers, predictable pipelines, efficient calling conventions (how functions pass arguments and return values)—may be underfunded.

Patterson’s RISC thinking emphasized spending silicon where real software can actually benefit.

A key RISC idea was to make the CPU’s “assembly line” easier to keep busy. That assembly line is the pipeline: instead of finishing one instruction completely before starting the next, the processor breaks work into stages (fetch, decode, execute, write-back) and overlaps them. When everything flows, you complete close to one instruction per cycle—like cars moving through a multi-station factory.

Pipelines work best when each item on the line is similar. RISC instructions were designed to be relatively uniform and predictable (often fixed length, with simple addressing). That reduces “special cases” where one instruction needs extra time or unusual resources.

Real programs aren’t perfectly smooth. Sometimes an instruction depends on the result of a previous one (you can’t use a value before it’s computed). Other times, the CPU needs to wait for data from memory, or it doesn’t yet know which path a branch will take.

These situations cause stalls—brief pauses where part of the pipeline sits idle. The intuition is simple: stalls happen when the next stage can’t do useful work because something it needs hasn’t arrived.

This is where hardware–software co-design shows up clearly. If the hardware is predictable, the compiler can help by rearranging instruction order (without changing the program’s meaning) to fill “gaps.” For example, while waiting on a value to be produced, the compiler might schedule an independent instruction that does not depend on that value.

The payoff is shared responsibility: the CPU stays simpler and fast on the common case, while the compiler does more planning. Together, they reduce stalls and increase throughput—often improving real performance without needing a more complex instruction set.

A CPU can execute simple operations in a few cycles, but fetching data from main memory (DRAM) can take hundreds of cycles. That gap exists because DRAM is physically farther away, optimized for capacity and cost, and limited by both latency (how long one request takes) and bandwidth (how many bytes per second you can move).

As CPUs got faster, memory didn’t keep up at the same rate—this growing mismatch is often called the memory wall.

Caches are small, fast memories placed close to the CPU to avoid paying the DRAM penalty on every access. They work because real programs have locality:

Modern chips stack caches (L1, L2, L3), trying to keep the “working set” of code and data close to the core.

This is where hardware–software co-design earns its keep. The instruction set architecture (ISA) and the compiler together shape how much cache pressure a program creates.

In everyday terms, the memory wall is why a CPU with a high clock speed can still feel sluggish: opening a large app, running a database query, scrolling a feed, or processing a big dataset often bottlenecks on cache misses and memory bandwidth—not on raw arithmetic speed.

For a long time, CPU discussions sounded like a race: whichever chip finished a task fastest “won.” But real computers live inside physical limits—battery capacity, heat, fan noise, and electricity bills.

That’s why performance per watt became a core metric: how much useful work you get for the energy you spend.

Think of it as efficiency, not peak strength. Two processors might feel similarly fast in everyday use, yet one can do it while drawing less power, staying cooler, and running longer on the same battery.

In laptops and phones, this directly affects battery life and comfort. In data centers, it affects the cost to power and cool thousands of machines, plus how densely you can pack servers without overheating.

RISC thinking nudged CPU design toward doing fewer things in hardware, more predictably. A simpler core can reduce power in several cause-and-effect ways:

The point isn’t that “simple is always better.” It’s that complexity has an energy cost, and a well-chosen instruction set and microarchitecture can trade a little cleverness for a lot of efficiency.

Phones care about battery and heat; servers care about power delivery and cooling. Different environments, same lesson: the fastest chip isn’t always the best computer. The winners are often the designs that deliver steady throughput while keeping energy use under control.

RISC is often summarized as “simpler instructions win,” but the more enduring lesson is subtler: the instruction set matters, yet many real-world gains came from how chips were built, not just what the ISA looked like on paper.

Early RISC arguments implied that a cleaner, smaller instruction set would automatically make computers faster. In practice, the biggest speedups frequently came from implementation choices that RISC made easier: simpler decoding, deeper pipelining, higher clocks, and compilers that could schedule work more predictably.

That’s why two CPUs with different ISAs can end up surprisingly close in performance if their microarchitecture, cache sizes, branch prediction, and manufacturing process differ. The ISA sets the rules; the microarchitecture plays the game.

A key Patterson-era shift was designing from data, not from assumptions. Instead of adding instructions because they seemed useful, teams measured what programs actually did, then optimized the common case.

That mindset often outperformed “feature-driven” design, where complexity grows faster than the benefits. It also makes trade-offs clearer: an instruction that saves a few lines of code might cost extra cycles, power, or chip area—and those costs show up everywhere.

RISC thinking didn’t only shape “RISC chips.” Over time, many CISC CPUs adopted RISC-like internal techniques (for example, breaking complex instructions into simpler internal operations) while keeping their compatible ISAs.

So the outcome wasn’t “RISC beat CISC.” It was an evolution toward designs that value measurement, predictability, and tight hardware–software coordination—regardless of the logo on the ISA.

RISC didn’t stay in the lab. One of the clearest through-lines from early research to modern practice runs from MIPS to RISC-V—two ISAs that made simplicity and clarity a feature, not a constraint.

MIPS is often remembered as a teaching ISA, and for good reason: the rules are easy to explain, the instruction formats are consistent, and the basic load/store model stays out of the compiler’s way.

That cleanliness wasn’t just academic. MIPS processors shipped in real products for years (from workstations to embedded systems), in part because a straightforward ISA makes it easier to build fast pipelines, predictable compilers, and efficient toolchains. When hardware behavior is regular, software can plan around it.

RISC-V renewed interest in RISC thinking by taking a key step MIPS never did: it’s an open ISA. That changes the incentives. Universities, startups, and large companies can experiment, ship silicon, and share tooling without negotiating access to the instruction set itself.

For co-design, that openness matters because the “software side” (compilers, operating systems, runtimes) can evolve in public alongside the “hardware side,” with fewer artificial barriers.

Another reason RISC-V connects so well to co-design is its modular approach. You start with a small base ISA, then add extensions for specific needs—like vector math, embedded constraints, or security features.

This encourages a healthier trade-off: instead of stuffing every possible feature into one monolithic design, teams can align hardware features with the software they actually run.

If you want a deeper primer, see /blog/what-is-risc-v.

Co-design isn’t a historical footnote from the RISC era—it’s how modern computing keeps getting faster and more efficient. The key idea is still Patterson-style: you don’t “win” with hardware alone or software alone. You win when the two fit each other’s strengths and constraints.

Smartphones and many embedded devices lean heavily on RISC principles (often ARM-based): simpler instructions, predictable execution, and strong emphasis on energy use.

That predictability helps compilers generate efficient code and helps designers build cores that sip power when you’re scrolling, but can still burst for a camera pipeline or game.

Laptops and servers increasingly pursue the same goals—especially performance per watt. Even when the instruction set isn’t traditionally “RISC,” many internal design choices aim for RISC-like efficiency: deep pipelining, wide execution, and aggressive power management tuned to real software behavior.

GPUs, AI accelerators (TPUs/NPUs), and media engines are a practical form of co-design: instead of forcing all work through a general-purpose CPU, the platform provides hardware that matches common computation patterns.

What makes this co-design (not just “extra hardware”) is the surrounding software stack:

If the software doesn’t target the accelerator, the theoretical speed stays theoretical.

Two platforms with similar specs can feel very different because the “real product” includes compilers, libraries, and frameworks. A well-optimized math library (BLAS), a good JIT, or a smarter compiler can produce large gains without changing the chip.

This is why modern CPU design is often benchmark-driven: hardware teams look at what compilers and workloads actually do, then adjust features (caches, branch prediction, vector instructions, prefetching) to make the common case faster.

When you evaluate a platform (phone, laptop, server, or embedded board), look for co-design signals:

Modern computing progress is less about a single “faster CPU” and more about an entire hardware-plus-software system that’s been shaped—measured, then designed—around real workloads.

RISC thinking and Patterson’s broader message can be boiled down to a few durable lessons: simplify what must be fast, measure what actually happens, and treat hardware and software as a single system—because users experience the whole, not the components.

First, simplicity is a strategy, not an aesthetic. A clean instruction set architecture (ISA) and predictable execution make it easier for compilers to generate good code and for CPUs to run that code efficiently.

Second, measurement beats intuition. Benchmark with representative workloads, collect profiling data, and let real bottlenecks guide design decisions—whether you’re tuning compiler optimizations, choosing a CPU SKU, or redesigning a critical hot path.

Third, co-design is where the gains stack up. Pipeline-friendly code, cache-aware data structures, and realistic performance-per-watt goals often deliver more practical speed than chasing peak theoretical throughput.

If you’re selecting a platform (x86, ARM, or RISC-V-based systems), evaluate it the way your users will:

If part of your work is turning these measurements into shipped software, it can help to shorten the build–measure loop. For example, teams use Koder.ai to prototype and evolve real applications through a chat-driven workflow (web, backend, and mobile), then re-run the same end-to-end benchmarks after each change. Features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback support the same “measure, then design” discipline Patterson pushed—just applied to modern product development.

For a deeper primer on efficiency, see /blog/performance-per-watt-basics. If you’re comparing environments and need a simple way to estimate cost/performance tradeoffs, /pricing may help.

The enduring takeaway: the ideas—simplicity, measurement, and co-design—keep paying off, even as implementations evolve from MIPS-era pipelines to modern heterogeneous cores and new ISAs like RISC-V.

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computing) emphasizes a smaller set of simple, regular instructions that are easy to pipeline and optimize. The goal isn’t “less capability,” but more predictable, efficient execution on the operations real programs use most (loads/stores, arithmetic, branches).

CISC offers many complex, specialized instructions, sometimes bundling multiple steps into one. RISC uses simpler building blocks (often load/store + ALU ops) and relies more on compilers to combine those blocks efficiently. In modern CPUs, the line is blurry because many CISC chips translate complex instructions into simpler internal operations.

Simpler, more uniform instructions make it easier to build a smooth pipeline (an “assembly line” for instruction execution). That can improve throughput (close to one instruction per cycle) and reduce time spent handling special cases, which often helps both performance and energy use.

A predictable ISA and execution model lets compilers reliably:

That reduces pipeline bubbles and wasted work, improving real performance without adding complicated hardware features that software won’t use.

Hardware–software co-design is an iterative loop where ISA choices, compiler strategies, and measured workload results inform each other. Instead of designing a CPU in isolation, teams tune the hardware, toolchain, and sometimes OS/runtime together so real programs run faster and more efficiently.

Stalls happen when the pipeline can’t proceed because it’s waiting on something:

RISC-style predictability helps both hardware and compilers reduce the frequency and cost of these pauses.

The “memory wall” is the widening gap between fast CPU execution and slow main-memory (DRAM) access. Caches (L1/L2/L3) mitigate it by exploiting locality (temporal and spatial), but cache misses can still dominate runtime—often making programs memory-bound even on very fast cores.

It’s a metric of efficiency: how much useful work you get per unit of energy. In practice it affects battery life, heat, fan noise, and data-center power/cooling costs. Designs influenced by RISC thinking often aim for predictable execution and less wasted switching, which can improve performance per watt.

Because many CISC designs adopted RISC-like internal techniques (pipelining, simpler internal micro-ops, heavy emphasis on caches and prediction) while keeping their legacy ISA. The long-term “win” was the mindset: measure real workloads, optimize the common case, and align hardware with compiler/software behavior.

RISC-V is an open ISA with a small base and modular extensions, making it well-suited to co-design: teams can align hardware features with specific software needs and evolve toolchains in public. It’s a modern continuation of the “simple core + strong tools + measurement” approach described in the article. For more, see /blog/what-is-risc-v.